|

|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

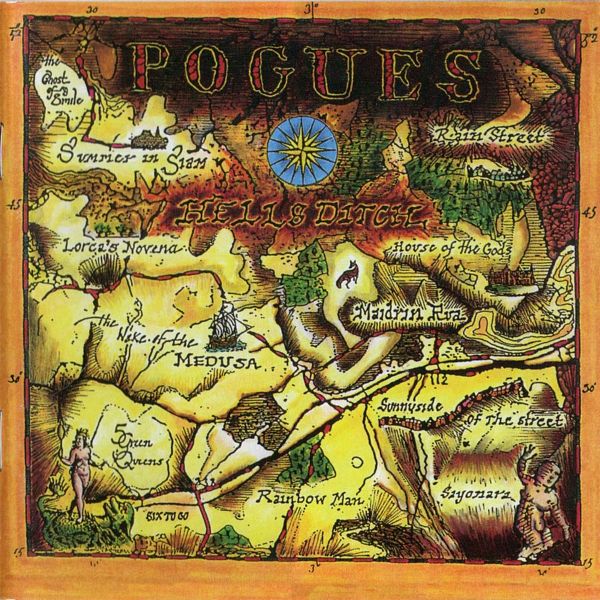

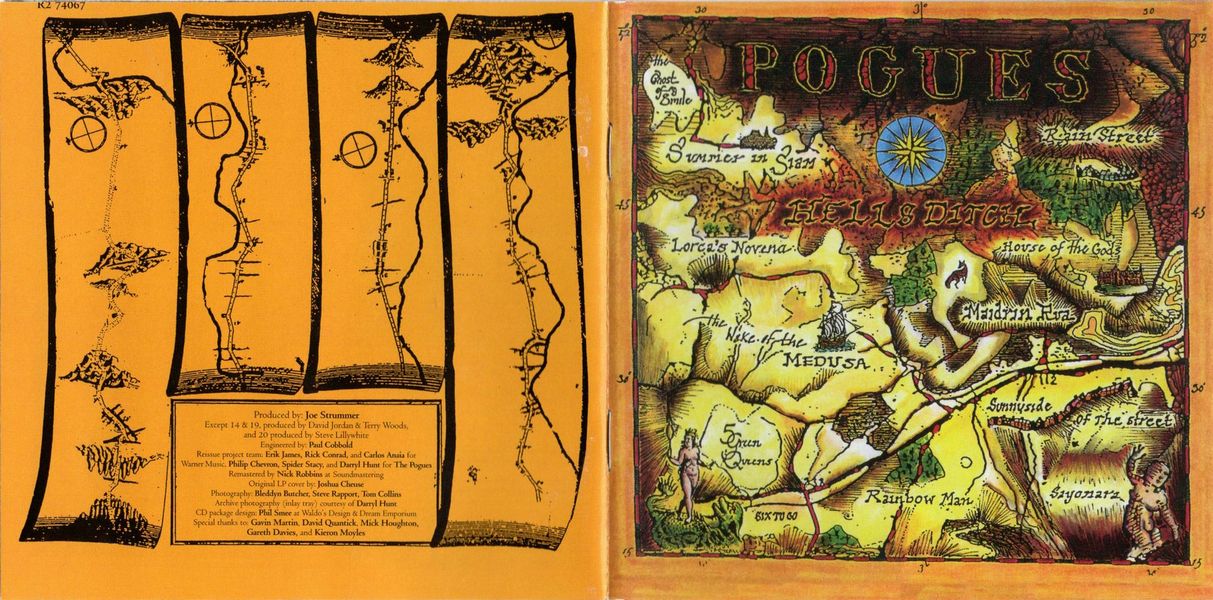

The military metaphor chosen for the title of The Pogues' 5th album, their List to feature songwriter and frontman Shane MacGowan, was certainly apt …

The band had fought from the back room of a Kings Cross pub, to become internationally renowned live attraction like no other. In MacGowan they had the genuine article, a one of a kind songwriter, capable of pure gold hack journeys into a dark night of the soul.

But the price the band and the singer had paid — bruised egos, nervous exhaustion, empty bottles, lost weekends — was beginning to mount.

Perhaps it was more than just coincidence that the birth of rock n' roll in the U.K. happened around the same time as national service ceased.

For many young males looking to break the bonds of their family and social background, joining a band became the most exciting proving ground, an escape route that replaced the old conformist military options. Join a band and see the world — go on tours of duty and experience a rites of passage, pledge allegiance to serve a higher power, get your kicks while serving your art.

The rewards could certainly be high but so could the casualty rate. The Pogues had seen many of their heroes and influences such as The Sex Pistols and The Clash crash and burn in premature kamikaze style. True, MacGowan and The Pogues had helped his childhood heroes The Dubliners celebrate 25 years together when they released 'The Irish Rover' duet in 1987.

But even The Dubliners had not made it through unscathed and the quarter century celebration took place long after the toils of the troubadour life had hastened the demise of Luke Kelly, a man who had been a formative influence on Shane's raw, hard vocal.

MacGowan's capacity for self destruction and his earlier childhood problems with paranoia and mental illness were known factors before The Pogues had formed. For the first five years of their assault on the shiny spires citadels of pop, where the drawbridges were manned to keep out the riff raff, Shane's reckless impulses had actually served the band well.

Who cares whether The Pogues reputation for ferocious partying was justified or not. As someone who came over a little faint in their company more than once I'd have to say, hand on heart — it was! But the point was it was matched by a series of records that held strong to MacGowan's dream. The Pogues had actually done what they set out to do — mixed the emancipatory charge of punk with hard truths and plaintive poetry of Irish folk and brought it to the masses.

However even at their peak the strain had been showing. On the American west coast tour in December 1987 I recall a long delay for the band's minibus as Shane stood howling and ranting in a layby, refusing to get on board for the 90-minute ride until he was suitably equipped with alcohol.

Despite the success of "Fairytale Of New York' and the If I Should Fall from Grace With God album, crisis point was reached the following July. Just as 'Fiesta' hit the U.K. chart, a song Shane later

claimed to detest, the singer collapsed at Heathrow Airport while on route to California for a 10-day tour of the West Coast with Bob Dylan. In a sign of what was to come after Hell's Ditch was complete the band had played the Dylan tour without him.

Tensions had increased throughout the recording of the band's difficult 4th album, Peace and Love, where the recording problems were exacerbated by MacGowan's determination to gleefully jump into the acid house explosion at the deep end.

Recognizing the scene that would turn The Happy Mondays into stars as a new cultural upsurge — as exciting and challenging to society as punk had been — MacGowan was keen to be a part of it.

"Young white psychopaths, young black psychopaths, young gay psychopaths — all creeds and races together on Ecstasy dancing in a conga line connecting like a great fucking swamp of humanity," he enthused to Nick Kent. But, addled on acid, Shane was now fighting on several fronts. At the same time as he dreamed of venturing into what was, for The Pogues, the musical no man's land of Acieed, he was also bemoaning the way he thought he was being sidelined in his own band.

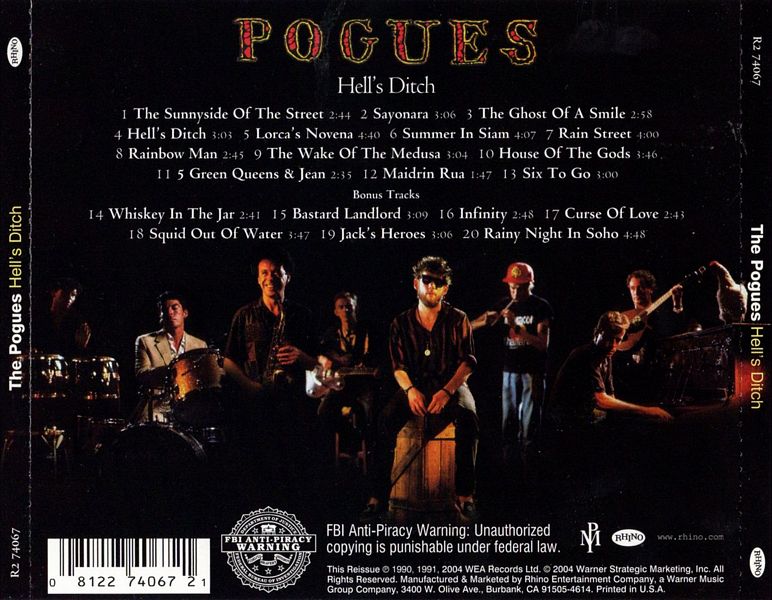

The band did get a chance to re-assert their Irish connections when they reunited with The Dubliners to record the unofficial Irish World Cup anthem 'Jack's Heroes.' Backed by a version of the traditional song 'Whiskey in The Jar,' a 1973 hit for Thin Lizzy, it became their first single of 1990, a safe consolidation with the faithful after the shakey Peace and Love.

Ironically 'Jack's Heroes' was composed by band members Spider Stacy and Terry Woods, not MacGowan. Based on the traditional song 'Wild Colonial Boy,' which celebrated rebel icon Jack Dugan, the title now referred to the Irish team's English manager Jack Charlton.

Spider and Terry's mischievous but good humoured lyric celebrated the international nature of the Irish team that would travel to Italy for the finals. It also took a sly swipe at the conflicting reputations of well-behaved Irish and boisterous English fans with the infamous hooligan element.

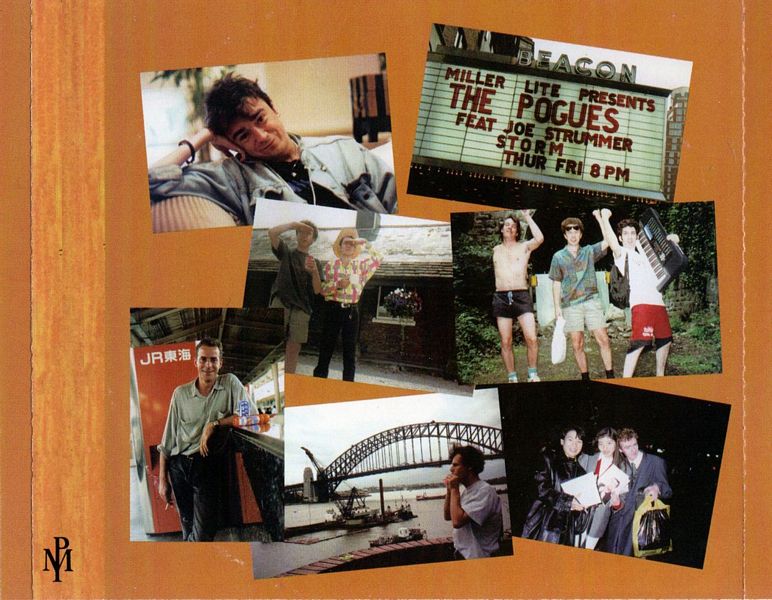

So, it was not surprising that in the U.K. charts the song only managed a lowly number 64 placing during the World Cup. By that time The Pogues had gathered in Rockfield studios in the Welsh countryside to record their 5th album. For Philip Chevron it would be a warmly remembered period, the bucolic surrounds of the studio where Horslips and Dave Edmunds had produced two of his favourite albums of the 1970s, provided a welcome respite from the clamour and exhaustion of the band's 5 years together.

"We needed to slow down and just be a band, without all the outside pressures. We would watch the football, make music and generally just be together," Chevron recalled.

Again, in a sign of what was to come, MacGowan's erratic attendances were not just confined to The Pogues' live shows, he would be an infrequent visitor to Rockfield.

The first song to emerge from the sessions, the lovely dreamy 'Summer in Siam' indicated that the singer had found a location of his own to escape the rigours of rebel stardom. This enchanted and exotic blues in waltz time, though filtered through Shane's world-weary Celtic muse, was set in Far East paradise.

"Thailand is heaven," Shane told Nick Kent, "a blinding civilisation of strong, gentle, good-hearted people with suss. An easy going race of people — a lot like the Irish before the British soldiers occupied their country."

In the past MacGowan had written songs with early influences inch as Liam Clancy and Tommy Makem in mind ('Broad Majestic Shannon'). Summer in Siam called to mind Frank Sinatra's saloon bar soliloquies, although Shane admitted it had begun life as a musical haiku, inspired by Tom Waits 'Johnsburg, Illinois.'

Thailand would be a recurring feature in the songs that Shane wrote for Hell's Ditch. 'Sayanora', which he once explained was about the relationship between a U.S. soldier and a Thai hooker, featured a reference to one of the country's most celebrated spirits, 'Mekong Whiskey,' in a chorus which cheekily referenced Van Morrison's Moonshine Whiskey.'

Contrary as ever, MacGowan would later claim that he "wasn't in the mood" to write Irish stuff for Hell's Ditch. Instead under the pressure of deadline he wrote rock songs with a Spanish or Latin flavour, an approach which actually favoured The Pogues' love of diversification and was gently encouraged by the album's producer, joe Strummer.

Strummer s role in helping Hell's Ditch become a triumph over adversity should not be underestimated. After the heated arguments that had occurred between Shane and Steve Lillywhite while recording the inappropriately titled Peace and Love album, the former Clash man had standing and a legacy which inspired the respect of the entire Pogues family. When he had first appeared with the band as a veteran reserve sharp shooter, called out of rocking retirement after Chevron had fallen ill, Joe was hypersensitive to any charges of upstaging or scene-stealing from Shane.

"The guy is one of the great poets, I would never do anything to undermine that, no way," he told me before joining the group onstage in Los Angeles 1997.

Strummer recognized that the band had the same spirit, sensitive chemistry and the same sense of musical adventure as The Clash.

Signed up to the rock n' roll battlefield for life, Strummer, faithful rocking Lieutenant, had always been there when The Pogues needed his input. He was a late choice to produce the album. Several other name producers, wary of the rapidly souring relationship between Shane and the others, had refused. And that was undoubtedly to the album's benefit.

To get into The Pogues atmosphere Strummer wore a cowboy hat he had acquired while shooting Alex Cox's movie Walker alongside Spider in Nicaragua, 3 years earlier. Joe later admitted his volatile approach to recording was inspired by Guy Stevens, the legendary mercurial producer who he'd worked with on The Clash's London Calling.

"Emotionally honesty is what works best, just let the band get on with it and react from the gut. I just learned to use whatever it takes, whether it's being polite and gentle or angry," he insisted.

While fortunate to have a fellow veteran of the rock 'n' roll wars to act as midwife at a critical point in their creative life, The Pogues were by now a fully developed and confident unit, capable of moments of sublime chemistry. Each member added their own distinctive contribution and the Finer/MacGowan songwriting team that had produced classics such as 'Fairytale Of New York' were on swaggering form with the upbeat 'Sunnyside Of the Street,' a song Finer began writing in New Zealand and MacGowan completed, filling it with images drawn from his experience of Far East culture.

On the title track they tackled the life and writing of French homosexual literary legend and jailbird Jean Genet, in typically graphic fashion. Genet was an obvious influence on MacGowan's hard vivid lyrics, though lines like "The guy in the bunk above gets sick/In the cell next door the lunatic/Starts screaming for his mother …" were as likely to have been inspired by MacGowan's teenage experiences in a mental hospital as the Frenchman's writing.

Another gay literary legend, Federica Garcia Lorca (1898-1956) was remembered on 'Lorca's Novena,' MacGowan pledging allegiance to the poet who was murdered, his body never recovered, in the Spanish Civil War.

The Pogues may have by now been bruised, bloodied, almost broken beyond repair, jet for their founding member's last hurrah they were able to summon up a defiant richness and ambition not heard since The Clash's glory days. The embattled theme ran through the record, a metaphor for the position the band now found themselves in, but also a way of linking whole swathes of art and history.

Terry Woods' weirdly desolate 'Rainbow Man' — haunted by loss but powered by a rebel heart that will not be still — recalled the suicide of Wolf Tone, the presiding figure in the 1798 United Irishmen rebellion. Finer s The Wake of Medusa' linked the tale behind the famous cover artwork used on Rum Sodomy & The Lash with a bitter commentary on the legacy of Margaret Thatcher.

Although MacGowan would later disown much of the record, the Dylanesque 'Five Green Queens And Jean' and the knack for matching happy-go-lucky tunes to an unflinching lyric ('Rain Street) were evidence that even in pressing times The Pogues' mastery held strong.

Although commercially it did little to redress the fall in fortunes that came with Peace and Love, Hell's Ditch was recognized as a vibrant return to form by many.

In the NME David Quantick awarded it a handsome 9 out of 10, Q gave it 4 stars out of 5 and in The Independent, critic Nicholas Lezard recognized 'Rain Street,' 'Sunnyside Of the Street' and 'The Ghost of a Smile' as being "as good as anything The Pogues had ever recorded."

Praise too came from America, where Boston Globe critic Jim Sullivan declared that "combined with exuberant melodies the songs of disgust, drunken excess and prison rape make for a terrific and oddly uplifting record."

For Phil Chevron the making of the album was The Pogues equivalent of one of those "Sixties Hippy things — getting your head together in the country."

But neither MacGowan or his comrades were ever likely to whitewash or cover up the wounds the band had taken as they waged their valiant campaign. The Pogues' strength on Hell's Ditch was to transpose such pain into songs that tackled a range of subject matter beyond the reach of most workaday pop bands.

"The whole album was like trying to find the light again. It is called Hell's Ditch because that is kind of where we were jammed into and we were looking to the 'Sunnyside Of the Street'," explains Chevron.

14 years after it was made, that determination to find the light is what still allows Hell's Ditch to shine.

GAVIN MARTIN