|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

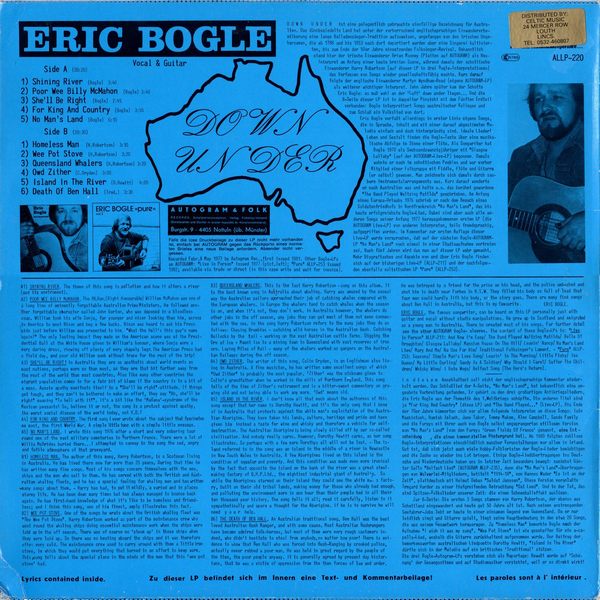

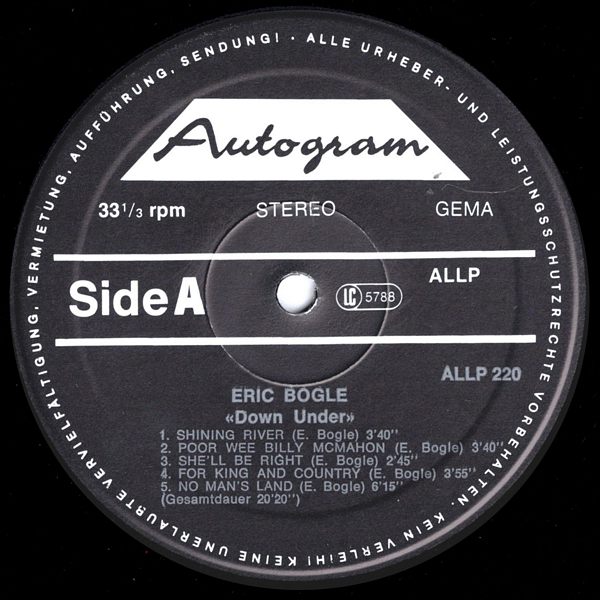

SHINING RIVER — The theme of this song is pollution and how it alters a river (and its environment).

POOR WEE BILLY McMAHON — The Rt. Hon.(Right Honourable) William McMahon was one of a long line of eminently forgettable Australian Prime Ministers. He followed another forgettable character called John Gorton, who was deposed in a bloodless coup. William took his wife Sonja, far younger and nicer looking than him, across to America to meet Nixon and beg a few bucks. Nixon was heard to ask his Press aide just before William was presented to him. "What the Hell's this guy's name again?" The only lasting impact they made on the American scene was at the Presidential Ball at the White House given in William's honour, where Sonja wore a very daring dress, showing off plenty of very shapely legs. The American Press had a field day, and poor old William sunk without trace for the rest of the trip!

SHE'LL BE RIGHT! — In Australia they are as apathetic about world events as most nations, perhaps more so than most, as they are that bit further away from the rest of the world than most countries. Also like many other countries the migrant population comes in for a fair bit of blame if the country is in a bit of a mess. Aussie apathy manifests itself in a "She'll be right" — attitude. If things get tough, and they can't be bothered to make an effort, they say "Ah, she'll be right" meaning "To hell with it!". It's a bit like the 'Mañana' — syndrome of the Mexican peasants! So, believe it or not, the song is a protest against apathy, the worst social disease of the world today, not V.D.!

FOR KING AND COUNTRY — The first song I ever wrote about the subject that fascinates me roost, the first World War. A simple little tune with a simple little message.

NO MAN'S LAND — I wrote this song 1976 after a short and very sobering tour round one of the vast military cemeteries in Northern France. There were a lot of Willie McBrides buried there … I attempted to convey in the song the sad, angry and futile atmosphere of that graveyard.

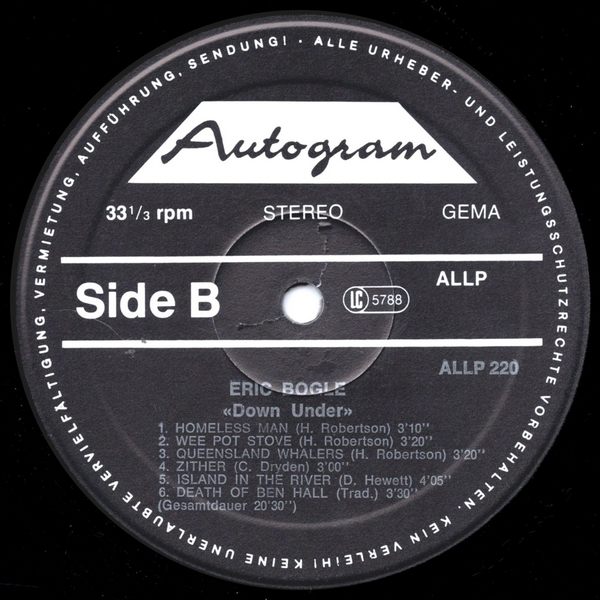

HOMELESS MAN — The author of this song, Harry Robertson, is a Scotsman living in Australia. He has lived there now for more than 25 years. During that time he has written many fine songs. Most of his songs concern themselves with the sea, ships and the men who sail in them. He has served with both the British and Australian whaling fleets, and he has a special feeling for whaling men and has written many songs about them. Harry has had, to put it mildly, a varied and in places stormy life. He has been down many times but has always managed to bounce back again. He has first-hand knowledge of what it's like to be homeless and friendless; and I think this song, one of his finest, amply illustrates this fact.

WEE POT STOVE — One of the songs he wrote about the British whaling fleet was "The Wee Pot Stove". Harry Robertson worked as part of the maintenance crew who went round the whaling ships doing essential maintenance work when the ships were laid up in the off season. There was of course no 'steam up' in these ships when they were laid up. So there was no heating aboard the ships and it was therefore offer very cold. The maintenance crew used to carry around with them a Tittle iron stove, in which they would put everything that burned in an effort to keep warm. This song tells about the special place in the minds of the men that this 'wee pot stove' had.

QUEENSLAND WHALERS — This is the last Harry Robertson — song on this album. It is the best known song in Australia about whaling. Harry was amused by the casual way the Australian sailors approached their job of catching whales compared with the European whalers. In Europe the whalers tend to catch whales when the season is on, and when it's not, they don't work. In Australia however, the whalers do other jobs in the off season, any jobs they can get most of them not even connected with the sea. In the song Harry Robertson refers to the many jobs they do as follows: Chasing Brumbies — catching wild horses in the Australian bush. Catching Bullocks by the tail — working on the vast Australian cattle farms. Digging the Ore at Isa — Mount Isa is a mining town in Queensland with vast reserves of iron ore. Laying Miles of Rail — many of the whalers worked as gangers on the Australian Railways during the off season.

OWD ZITHER — The writer of this song, Colin Dryden, is an Englishman also living in Australia. A fine musician, he has written some excellent songs of which "Owd Zither" is probably the most popular. 'Zither' was the nickname given to Colin's grandfather when he worked in the mills of Northern England. This song tells of the time of Zither's retirement and is a bitter-sweet commentary on growing old and not being able to work any more. 'Owd' means old.

ISLAND IN THE RIVER — I don't know all that much about the authoress of this song except that her name is Dorothy Hewitt, and it's the only song that I know of in Australia that protests against the white man's exploitation of the Australian Aborigine. They have taken his lands, culture, heritage and pride and have given him instead a taste for wine and whisky and therefore a vehicle for self-destruction. The Australian Aborigine is being slowly killed off by our so-called civilisation. And nobody really cares. However, Dorothy Hewitt cares, as her song illustrates. So perhaps with a few more Dorothys all will not be lost. — The Island referred to in the song was an island in the middle of a river in Newcastle in New South Hales in Australia. A few Aborigines lived on this island in the condition of squalor and poverty. And this condition was made even more ironical by the fact that opposite the island on the bank of the river was a great steel-making factory of B.H.P. Ltd., the mightiest industrial giant of Australia. So while the Aborigines starved on their island they could see the white man's factory, built on their old tribal lands, making money for those who already had enough, and polluting the environment more in one hour than their people had in all their ten thousand year history. The song tells it all; read it carefully, listen to it sympathetically and spare a thought for the Aborigine. If he is to survive he will need your help.

THE DEATH OF BEN HALL — An Australian traditional song. Ben Hall was the best loved Australian Bush Ranger, and with some cause. Most Australian Bushrangers have become admired folk-heroes, but most of them were very rough customers indeed, who didn't hesitate to steal from anybody, no matter how poor! There is evidence to show that Ben Hall who was forced into Bush-Ranging by crooked police, actually never robbed a poor man. He was held in great regard by the people of the time, the poor people anyway. It is generally agreed by present day historians, that he was a victim of oppression from the then forces of law and order.

He was betrayed by a friend for the price on his head, and the police ambushed and shot him to death near Forbes in N.S.W. They filled his body so full of lead that four men could hardly lift his body, so the story goes. There are many fine songs about Ben Hall in Australia, but this is my favourite.

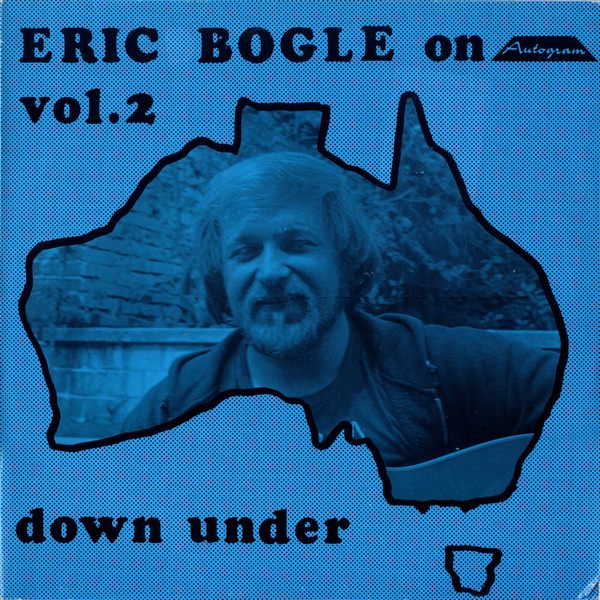

ERIC BOGLE

ERIC BOGLE, the famous songwriter, can bo heard on this LP personally just with guitar and vocal without studio manipulations. He grew up in Scotland and emigrated as a young man to Australia. There he created most of his songs.

Eric Bogle seemed confused by it all. He sat upright in a chair in the deserted dining-room of the Garrion Hotel in Motherwell, his powerful hand wrapped around a pint glass and gave me a bemused and bewildered look. Everytime I meet Eric he seems in the same frame of mind. He just cannot grasp what all the fuss is about and it brings a smile to his face as he talks.

It's merely a £20 folk club gig, yet the people have turned out in droves to hear this chunky, little country boy from Peebles sing his own songs and one song in particular, 'The band played Waltzing Matilda', which has made Eric Bogle's name among the folk fraternity of Britain and Australia where he wrote it. He won't be allowed off stage until he sings it. And when he does, people join in on every word. That's what he cannot understand.

The song has now been recorded several times. June Tabor, Alex Campbell and Iain Mackintosh have put it on disc in the UK. In Australia, an Irishman called John Curry put it in the charts and a band, The Bushwackers, have released it as a single.

It is one song; and Eric Bogle has suddenly found himself a wanted man.

Eric took a swig from his pint, lit up a cigarette and eyed my tape-recorder. Speaking to the press after coming off stage is something he is trying to get used to.

He's still a country lad at heart. He remembers leaving his native Borders town of Peebles and coming to work in Glasgow. The pace of life and the loneliness of a big city sent him scurrying home to the tweed mills within a year. Yet he managed to pluck up the courage and emigrate to Australia where he made a name for himself in folk circles and landed a job which now gives him a hefty wage packet; somewhere in the region of £12,000 per year as an accountant. For the country laddie everything has come good. But he manages to prevent himself from crossing the line into becoming a full-time, professional singer-songwriter.

Bogle stays aloof. That's the way he wants it.

He began his musical career at 16, playing in a pop band around Peebles. Three years later he met the man who was to influence and change his life. Dave McQueen came to Peebles as a Glasgow overspill worker. He was a folk singer and a Communist.

'He was the first Commie I met', said Bogle, toying thoughtfully with his glass. 'I found out he was just like other people. He interested me in Communism and folk music. The people whose politics I admired were into folk. Dave McQueen was everything I wanted to be. I became a pint-sized Dave McQueen'.

That was all to change when McQueen died tragically and the young Eric was left at a loose end. Life was very dull and narrow in Peebles. It was a case of working in the woollen mills or nothing. Eric chose to emigrate to Australia and he left Scotland in 1969. He arrived in the country's capital, Canberra, and got a job as a layman hand in a builder's yard for 55 dollars a week, big money compared to what he had been taking home in Peebles. He was to stay in Canberra for five years.

At first he found he wasn't making new friends quickly enough.

'So I joined a rugby club, but I found I was past the rugger-bugger rip her knickers away syndrome. Then I remembered that the people I had liked best of all in Scotland were those into folk circles. So I made frantic efforts to find the Australian folk scene. It wasn't easy. It was well-hidden'. He found his friends on the university campus in Canberra, the only place that would tolerate long-haired 'freaks' playing guitars and singing folk music.

It was at this time that Bogle began writing his own songs. Little did he know what was in store for him.

The first song was 'Glasgow lullaby'.

'I used to sing traditional songs only, so I went to Australia with the idea of being the only Scots traditional singer in the country, which was rubbish. There were a lot of good singers around. If I had stuck the traditional scene. I would have been Mr. Average. But I can't say I had to write, although it was an intentional mood.

'In Australia I had mental freedom. I had no hassles with family or parents. I didn't have to live up to anything.

'The trouble though with singer-songwriters is that all of it is in the mind. You get a name in any field of music for writing your own material and the pressure is on constantly. For the last six months I haven't been able to write a note or a word. I've wanted to desperately. Everytime someone sings 'Matilda', I've said to myself I must follow that somehow. But I've been constipated' .

After 'Glasgow lullaby' Eric penned 'She'll be right' and 'I hate wogs'. These were his first funny songs.

'I discovered I could reach people by humour. Until then I had been a very intense singer. But they may be funny songs, but there is always bite or message to the lyrics'.

Eric continued writing good songs for four years until 1974 when he witnessed the annual Anzac Day parade of ex-Australian soldiers who fought at Gallipoli in the 1914-18 War. The parade gave him the inspiration to write 'The band played Waltzing Matilda', the song which was to give him recognition.

'I watched the parade and all the crap that goes with the so-called glory. I was annoyed by the whole thing. The people on these parades generally never saw action. All the real soldiers were killed. In Australia, Anzac Day is merely an excuse for a booze-up. When I get annoyed by things, I write songs about them'.

Bogle wrote the song in seven hours. He locked himself in a room in his house and composed with a bottle of whisky for comfort.

He first sang Matilda' in the Kingston Hotel, Canberra. He forgot some of the words, earned a few polite handclaps and then dropped the number from his repertoire.

Eric dug the song out again for a song festival in Brisbane. The judges placed him and 'Matilda' third, but their decision caused a near-riot with the crowd who felt he should have won.

The resulting publicity established Matilda'. John Curry sent it up the charts. Word rapidly spread and soon everyone was including it in their programme. It caught on in the UK and was recorded three times. Overnight 'Matilda' and Bogle were sensations of the folk world. That puzzles Eric greatly.

'I've written some bloody good songs since. For example. 'No man's land' and 'Now I'm easy'. I just don't know why 'Matilda' has the appeal it has'.

Eric returned to Scotland last May, virtually unaware of the popularity of 'Matilda' in Britain.

'I didn't think I stood a chance of breaking into the UK folk scene. I thought it would be pointless trying'.

But with the help of some folk club organisers and an interview on Glasgow's Radio Clyde, Eric was suddenly in demand. Folk club committees up and down the country want him to appear and a Glasgow record label are talking about an album.

But Eric has already got his future mapped out. He intends returning to Australia next year via America to resume work as an accountant.

'Music is just a hobby with me', he admitted. 'I mean, what could I do here in Britain? I could become a pro folk singer. Anybody could. But I see the way most of them live and it's not for me. When you've got to depend on your music for a living, your attitude must change. I don't really need the money.

'My main ambition is simply to see other people sing and record my songs. I want to go back to Australia and send tapes of my songs over to Britain and have people pounce on them and say. 'ah, what's Eric Bogle written this time!'

'To be cliche-ridden, it's my jump for immortality. I'd like to think that 100 years after I've gone, people will sing 'Matilda'. I want to leave something behind me.

'I may not write another song which appeals to people, but at least I have written 'Matilda'

Eric shook my hand when we finished our interview, picked up his pint and strolled off to join in conversation with some fellow 'folkies'.

They greeted him and treated him like a star. The folk world isn't supposed to breed stars. Eric doesn't want the fuss and attention, but the popularity of just one song has pushed him into it and it will be difficult to find obscurity again.