|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

This is how new folk songs should be: simple on the outside and rich on the inside. Here is the well-balanced mix. Bogle's songs are not apolitical, but they are not disguised. Here, too, the top spot.

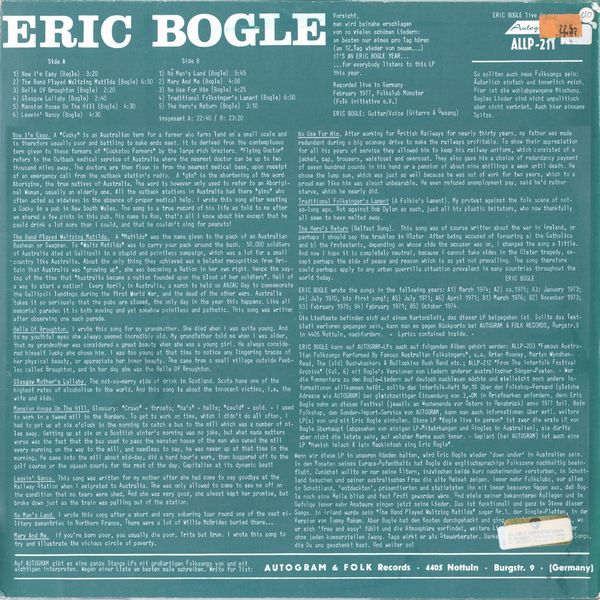

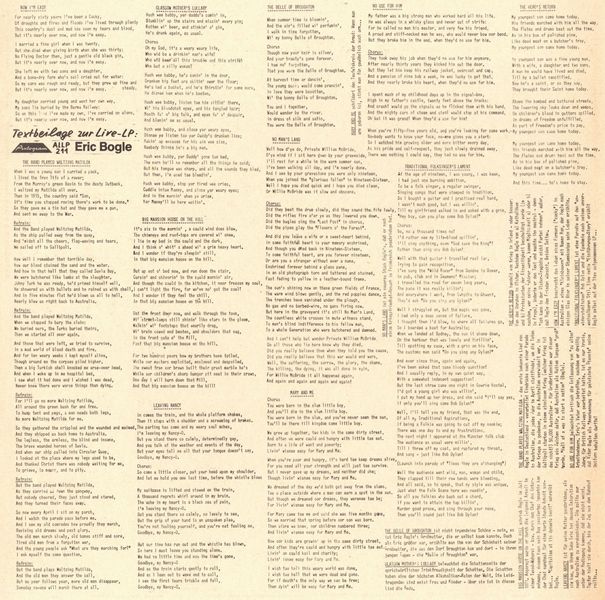

Now I'm Easy — A "Cocky" is an Australian term for a farmer who farms land on a small scale and is therefore usually poor and battling to make ends meet. It is derived from the contemptuous term given to these farmers of "Cockatoo Farmers" by the large rich Graziers. "Flying Doctor" refers to the Outback medical service of Australia where the nearest doctor can be up to two thousand miles away. The doctors are then flown in from the nearest medical base, upon receipt of an emergency call from the outback station's radio. A "gin" is the shortening of the word Aborigine, the true natives of Australia. The word is however only used to refer to an Aboriginal Woman, usually an elderly one. All the outback stations in Australia had there "gins" who often acted as midwives in the absence of proper medical help. I wrote this song after meeting a Cocky in a pub in New South Wales. The song is a true record of his life as told to me after we shared a few pints in this pub. His name is Ron, that's all I know about him except that he could drink a lot more than I could, and that he couldn't sing for peanuts!

The Band Played Waltzing Matilda — A "Matilda" was the name given to the pack of an Australian Bushman or Swagman. To "Waltz Matilda" was to carry your pack around the bush. 50,000 soldiers of Australia died at Gallipoli in a stupid and pointless campaign, which was a lot for a small country like Australia. About the only thing they achieved was a belated recognition from Britain that Australia was "growing up", she was becoming a Nation in her own right. Hence the saying of the time that "Australia became a nation founded upon the blood of her soldiers". Hell of a way to start a nation! Every April, in Australia, a march is held on ANZAC Day to commemorate the Gallipoli landings during the first World War, and the dead of the other wars. Australia "'takes it so seriously that the pubs are closed, the only day in the year this happens. Like all memorial parades it is both moving and yet somehow pointless and pathetic. This song was written after observing one such parade.

Belle Of Broughton — I wrote this song for my grandmother. She died when I was quite young. And to my youthful eyes she always seemed incredibly old. My grandfather told me when I was older, that my grandmother was considered a great beauty when she was a young girl. He always considered himself lucky she chose him. I was too young at that time to notice any lingering traces of her physical beauty, or appreciate her inner beauty. She came from a small village outside Peebles called Broughton, and in her day she was the Belle Of Broughton.

Glasgow Mother's Lullaby — The not-so-merry side of drink in Scotland. Scots have one of the highest rates of alcoholism in the world. And this song is about the innocent victims, i.e. the wife and kids.

Mansion Hoose On The Hill — Glossary: "Craws" = throats; "ha's" = halls; "cauld" = cold. — I used to work in a tweed mill in the Borders. To get to work on time, which I didn't do all often, I had to get up at six o'clock in the morning to catch a bus to the mill which was a number of miles away. Getting up at six on a Scottish winter's morning was no joke, but what made matters worse was the fact that the bus used to pass the mansion house of the man who owned the mill every morning on the way to the mill, and needless to say, he was never up at that time in the morning. He came into the mill about mid-day, did a hard hour's work, then buggered off to the golf course or the squash courts for the rest of the day. Capitalism at its dynamic best!

Leavin' Nancy — This song was written for my mother after she had come to say goodbye at the Railway Station when I emigrated to Australia. She was only allowed to come to see me off on the condition that no tears were shed. And she was very good, she almost kept her promise, but broke down just as the train was pulling out of the station.

No Man's Land — I wrote this song after a short and very sobering tour round one of the vast military cemeteries in Northern France, There were a lot of Willie McBrides buried there…

Mary And Me — If you're born poor, you usually die poor. Trite but true. I wrote this song to try and illustrate the vicious circle of poverty.

No Use For Him — After working for British Railways for nearly thirty years, my father was made redundant during a big economy drive to make the railways profitable. To show their appreciation for all his years of service they allowed him to keep his railway uniform, which consisted of a jacket, cap, trousers, waistcoat and overcoat. They also gave him a choice of redundancy payment of seven hundred pounds in his hand or a pension of about nine shillings a week until death. He chose the lump sum, which was just as well because he was out of work for two years, which to a proud man like him was almost unbearable. He even refused unemployment pay, said he'd rather starve, which he nearly did.

Traditional Folksinger's Lament (A Folkie's Lament) — My protest against the folk scene of not-so-long ago. Not against Bob Dylan as such, just all his plastic imitators, who now thankfully all seem to have melted away.

The Hero's Return (Belfast Song) — This song was of course written about the war in Ireland, or perhaps I should say the troubles in Ulster After being accused of favouring a) the Catholics and b) the Protestants, depending on whose side the accuser was on, I changed the song a little. And now I hope it is completely neutral, because I cannot take sides in the Ulster tragedy, except perhaps the side of peace and reason which is as yet not prevailing. The song therefore could perhaps apply to any urban guerrilla situation prevalent in many countries throughout the world today.

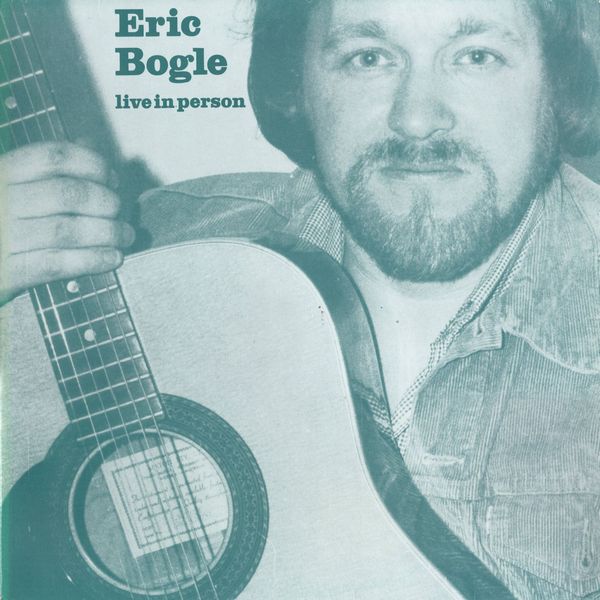

Eric Bogle

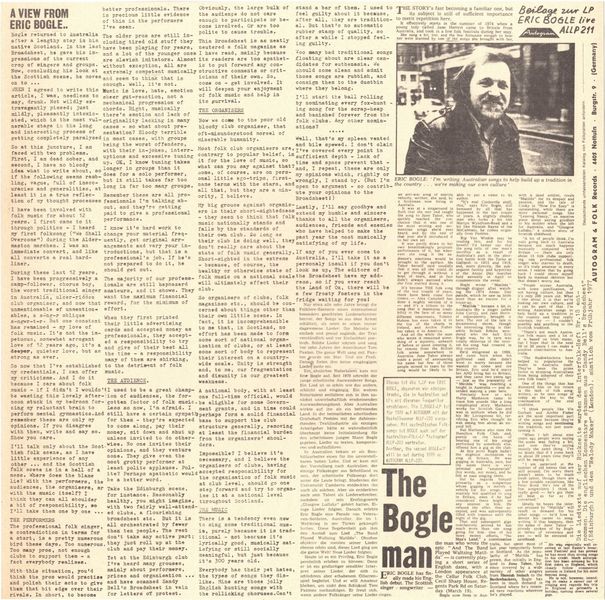

A VIEW FROM ERIC BOGLE …

Bogle returned to Australia after a lengthy stay in his native Scotland. In the last Broadsheet, he gave his impressions of the current crop of singers and groups. Now, concluding his look at the Scottish scene, he moves on to …

WHEN I agreed to write this article, I was, needless to say, drunk. Not wildly extravagantly pissed; just mildly, pleasantly intoxicated, which is the most vulnerable stage in the long and interesting process of getting completely paralysed

So at this juncture, I am faced with two problems. First, I am dead sober, and second, I have no bloody idea what to write about, so if the following seems rambling, vague, full of inaccuracies and generalities, at least it is a true reflection of ay thought processes

'I have been involved with folk music for about 12 years. I first came to it through politics — I heard my first folksong ("We Shall Overcome") during the Alder-mast on marches. I was an immediate convert, and like all converts a real hardliner.

During these last 12 years, I have been progressively a camp-follower, chorus boy, the worst traditional singer in Australia, ulcer-ridden club organiser, and now that unmentionable of unmentionables, a s-ng-r oblique s-ngwr-t-r, But one constant has remained — my love of folk music. It's not the impetuous, somewhat arrogant love of 12 years ago, it's a deeper, quieter love, but as strong as ever.

So now that I've established my credentials, I can offer my criticisms. And I do it because I care about folk music — if I didn't I wouldn't be wasting this lovely afternoon stuck in ray bedroom forcing my reluctant brain to perform mental gymnastics. And remember these are only my opinions. If you disagree with them, write and say so. Show you care.

I'll talk only about the Scottish folk scene, as I have little experience of any other … and the Scottish folk scene is in a hell of a mess. 'Where does the blame lie? With the performers, the audiences, the organisers, or with the music itself? I think they can all shoulder a bit of responsibility, so I'll take them one by one …

THE PERFORMERS

The professional folk singer, a contradiction in terms for a start, is a pretty numerous bird these days. Too numerous. Too many pros, not enough clubs to support them — a fact everybody realises.

With this situation, you'd think the pros would practise and polish their acts to give them that bit edge over their rivals. In short, to become better professionals. There is precious little evidence of this in the performers I've seen.

The older pros are still including tired old stuff they have been playing for years, and a lot of the younger ones are slavish imitators. Almost without exception, all are extremely competent musically and seem to think that is enough. Well, it's not.

Music is love, hate, emotion sheer gut-reaction, not a mechanical progression of chords. Right, musically there's emotion and lack of originality lacking in many cases — so what about presentation? Bloody terrible in most cases, with groups being the worst offenders, with their in-jokes, interruptions and excessive tuning up. OK, I know tuning takes longer in groups than it does for a solo performer, but it still takes far too long in far too many groups.

Remember these are all professionals I'm talking about, and they're getting paid to give a professional performance.

I know it's hard work to change your material frequently, get original arrangements and vary your introductions, but that is a professional's job. If he's not prepared to do it, he should get out.

The majority of our professionals are still haphazard amateurs, and it shows. They want the maximum financial reward, for the minimum of effort.

When they first printed their little advertising cards and accepted money as professionals, they accepted a responsibility to try and give of their best all the time — a responsibility many of them are shirking, to the detriment of folk music.

THE AUDIENCE

I used to be a great champion of audiences, the forgotten factor of folk music. Less so now, I'm afraid. I still have a certain sympathy for them — they're expected to come along, pay their money, sit down and shut up unless invited to do otherwise. No one invites their opinions, and they venture none. They give even the most grotty performer at least polite applause. Polite? Perhaps apathetic would be a better word.

Take the Edinburgh scene, for instance. Reasonably healthy, you might imagine, with two fairly well-attended clubs, a flourishing broadsheet etc. But it is all orchestrated by fewer than ten people. The rest don't take any active part; they just roll up at the club and pay their money.

Yet at the Edinburgh club I've heard many grouses, mainly about performers, prices and organisation … and have scanned Sandy Bell's Broadsheet in vain for letters of protest.

Obviously, the large bulk of the audience do not care enough to participate or become involved. Or are too polite to cause trouble.

This Broadsheet is as neatly neutered a folk magazine as I have read, mainly because its readers are too apathetic to put forward any constructive comments or criticisms of their own. So, come on — get involved. It will deepen your enjoyment of folk music and help in its survival.

THE ORGANISERS

Now we come to the poor old bloody club organiser, that oft-misunderstood morsel of miserable humanity.

Most folk club organisers are, contrary to popular belief, in it for the love of music, so what can you say against that? some, of course, are on personal little ego-trips, first-name terms with the stars, and all that, but they are a minority, I believe.

My big grouse against organisers is their short-sightedness — they seem to think that folk music nationally stands and falls by the standards of their own club. So long as their club is doing well, they don't really care about the state of folk music generally. Short-sighted in the extreme — because, of course, the healthy or otherwise state of folk music on a national scale will ultimately affect their club.

So organisers of clubs, folk magazines etc., should be concerned about things other than their own little scene. In fact, it is incomprehensible to me that, in Scotland, no effort has been made to form some sort of national organisation of clubs, or at least some sort of body to represent their interest on a countrywide scale. Unity is strength and, to me, our fragmentation and disunity is our greatest weakness.

A national body, with at least one full-time official, would be eligible for some Government grants, and in time could perhaps form a solid financial base to support the club structure generally, removing at least the financial burden from the organisers' shoulders.

Impossible? I believe it's necessary, and I believe the organisers of clubs, having accepted responsibility for the organisation of folk music at club level, should go one step forward and try to organise it at a national level throughout Scotland.

THE MUSIC

There is a tendency even now to sing some traditional music, purely because it is traditional — not because it's lyrically good, musically satisfying or still socially meaningful, but just because it's 300 years old.

Everybody has their pet hates, the types of songs they dislike. Mine are those jolly English hunting songs with the rollicking choruses. Can't stand a bar of them. I used to feel guilty about it because, after all, they are traditional. But that's no automatic rubber stamp of quality, so after a while I stopped feeling guilty.

Too many bad traditional songs floating about are clear candidates for euthanasia. We should come clean and admit those songs are rubbish, and consign them to the dustbin where they belong.

I'll start the ball rolling by nominating every fox-hunting song for the scrap-heap and banished forever from the folk clubs. Any other nominations?

Well, that's my spleen vented and bile spewed. I don't claim I've covered every point in sufficient depth — lack of time and space prevent that — and, I repeat, these are only my opinions which, rightly or wrongly, I stand by. (But I'm open to argument — so contribute your opinions to the Broadsheet!)

Lastly, I'll say goodbye and extend my humble and sincere thanks to all the organisers, audiences, friends and enemies who have helped to make the past year the most musically satisfying of my life.

If any of you ever come to Australia, I'll take it as a personally insult if you don't look me up, the editors of the Broadsheet have ray address, so if you ever reach the Land of Oz, there will be a few frosty Fosters in the fridge waiting for you!