|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

"We shall never conquer Ireland while the Bards are there".

A statement insightful, prescient, and four hundred years old. After making It, a furious Queen Elizabeth set about correcting the oversight, ordering her deputies to "hang the harpers wherever found." The shrewd old Queen had learned what the Irish always knew, that he who has the best ballads wins.

The Irish folk-memory, that faithful reflection of the common life of the people, remembers: the heroes and villains of our tradition resonating yet through the Irish consciousness.

I long ago came to understand that the ballads and the history are the same; our song tradition is both a dictionary of national biography and a sort of Enclyop?dia Hibernia. The ubiquitous balladry sings the stories of those who lived the events, leaving a legacy of poem and song that binds us to our past and country by their "condensed and gem-like history."

Balladry is perhaps better suited than narrative history to explain the driving forces behind events in Irish history, forces sufficiently compelling to send men out with hay-forks in 1798, and poets out with rhetoric in 1916. If you listen you may find that, even if you do not know the "what" of Irish history, the ballads will invariably tell you the "why."

In gratitude for the songs and stories this CD is dedicated to two "Rebel Hearts," my mother, Kathleen Doyle & great-grandmother Brigid Fitzgerald.

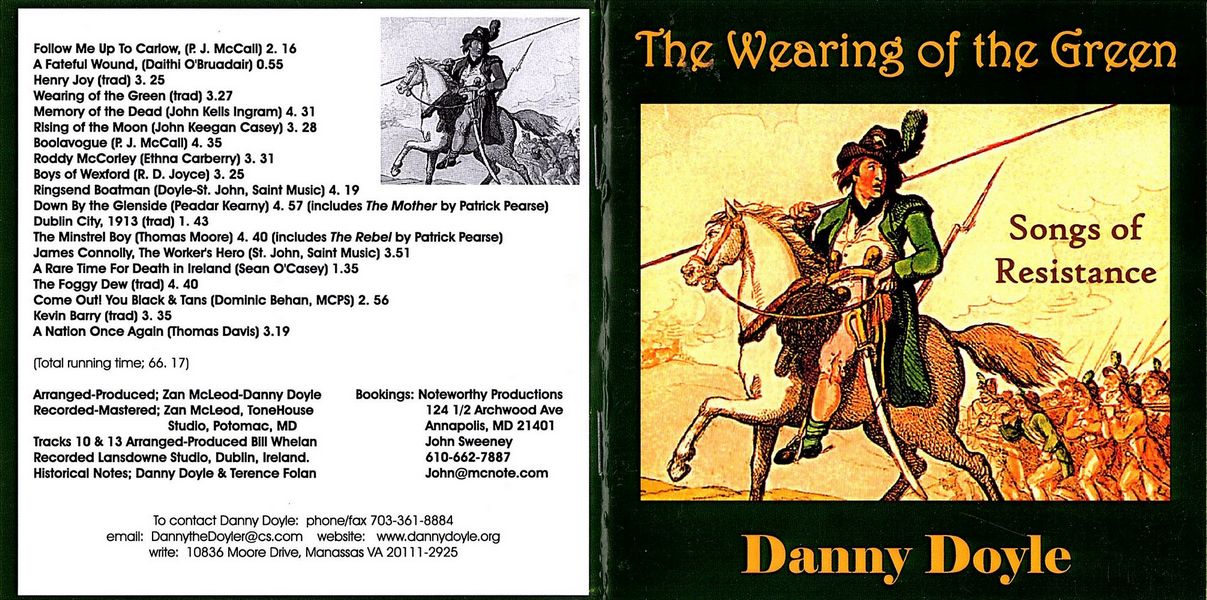

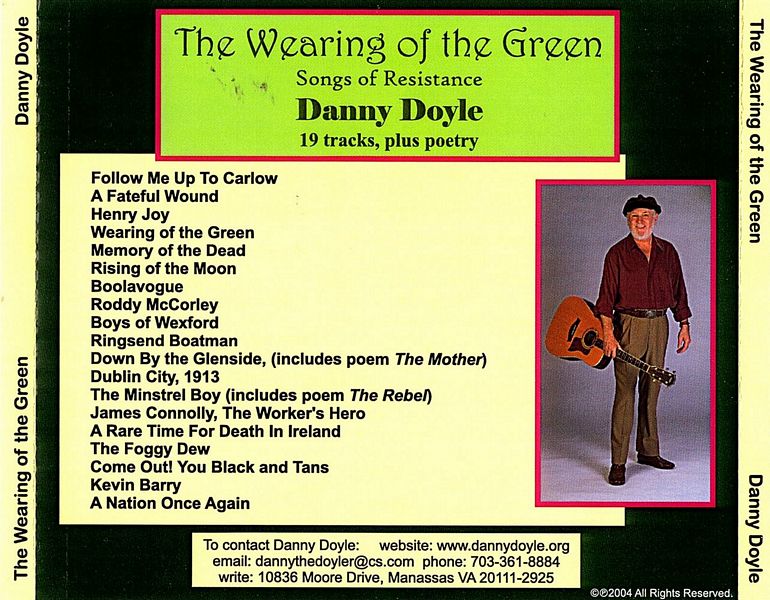

About the songs

Follow Me Up To Carlow — In the 16th century, Queen Elizabeth sent her armies into Ireland with instructions to find the powerful Irish clans, kill them and confiscate their castles and lands, an English custom wrought to perfection in Ireland. On September 3rd, 1580, General Lord Grey marched into Co. Wicklow in pursuit of the O'Byrnes of Glenmalure. Lord Grey's army climbed to the mountainous valley from the plains to the west, a fatal mistake. His soldiers, many of them in armour, sank in the boggy uplands, easy prey for Fiach McHugh O'Byrne's hardy kern who fell in fury upon them. Many a scion of the powerful English families died that morning in 1580. This is the war tune of the O'Byrne's. The Co. Wexford song writer Patrick Joseph McCall, in the late 19th century, set the lyrics to it.

A Fateful Wound (poem) — Written by Daithi O'Bruadair, one of the great Munster poets, this piece was inspired by the anguish O'Bruadair felt as he witnessed the plundering of Ireland in the 17th century. The dispossession of the Gael began in the 12th century when Pope Adrian IV, in a Papal Bull, granted to Henry 2nd, King of England, "The island of Ireland and all within it." This piece of outlandish chicanery is hardly surprising when we remember that Pope Adrian was Nicolas Breakspeare, an Englishman! After the slaughter of the Cromwellian wars, the surviving Irish were ordered To Hell or to Connaught." Anyone found east of the Shannon after a certain date would be hanged, "for not transporting." In a census of 1659 only slightly more than 500,000 Irish could be found to be counted. By 1703 barely 7% of the land was held by the native population, by the end of the century, the figure was 3%. The transformation of the Irish into a race of beggars was almost complete.

Henry Joy — Henry Joy McCracken was one of the leaders of the rebellion in the North of Ireland in 1798 and the wealthiest and most dedicated of the United Irishmen. McCracken's house in Belfast's Rosemary Lane had long been a centre of Celtic culture. It was there that Edward Bunting transcribed, thus preserving, the music of Ireland's wandering harpers. When the North rose in 1798, McCracken was commander-in-chief of the insurgent forces in Co. Antrim, the only founding member of the United Irishmen to actually take the field. As this ballad tells us, this Gaelic-speaking Church of Ireland rebel leader was publicly executed for his treason, to both Britain and his social class.

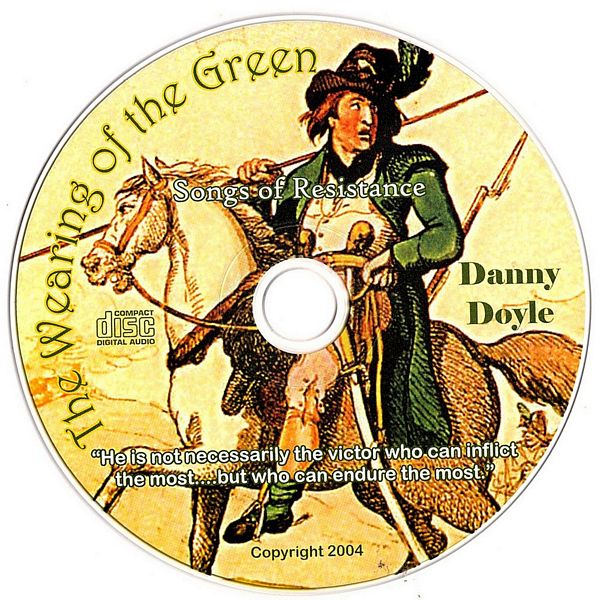

The Wearing of The Green — The colour green, adopted in the 1790s by Irish republicans from the French Tree of Liberty, has since been the symbol of Irish nationalism. In the late 1700's, the authorities in Ireland looked on the wearing of green as an act of defiance and the Militia were known to flog people in the streets for the offence. The Co. Cork writer Frank O'Connor said, "this little song, originally written in a pseudo-Irish dialect, probably an Ulster Presbyterian, and set to what seems to be an adaptation of a Scottish pibroch, is our real national anthem

Memory of the Dead — All the ballads of 1798, in one way or another, do what John Kells Ingram does in this one: they ask us to remember. Yet, while countries around the world glory in the memory of those who risked their lives to give birth to the sovereignty they enjoy today, Official Ireland seems hesitant to celebrate her own Bolivars, Garibaldis, and Washingtons. In a time when what actually happened in the past is often sacrificed on the altar of a modern political or academic agenda, it may be useful to occasionally ask such questions as, "Who fears to speak of '98" and, perhaps, "Why?" When this song was published in 1843, its author was a lad of twenty. Ingram would later become a professor at Trinity College, Dublin, and president of the Royal Irish Academy.

The Rising of the Moon — On the eve of the 1798 rebellion, a great expectancy hummed throughout the peasantry of Co. Wexford. Many of the common folk, convinced they were looked upon as treasonous in the eyes of the authorities, hid pikes and blades in anticipation of 'The Day.' Threescore years afterward, 14-year-old John Keegan Casey imagined that time when he wrote this song. The young Fenian poet captures the defiant excitement of the period vividly, and his may be the most widely known of all Irish ballads. Indeed, Rudyard Kipling, The Poet of British Imperialism,' heard it sung by a goat-herder in the mountains of Nepal around 1900. Casey, from Co. Longford, died in Dublin in 1870, age 24.

Boolavoque — Perhaps the most powerful of all the songs of 1798, this achingly beautiful late 19th century ballad by Patrick Joseph McCall was based on one written at the time of the rebellion. Typical of the "chronological ballads" of the era, it tells the story of Fr. John Murphy, from the action at The Harrow to his ultimate fate at Tullow, Co. Carlow, where he was discovered by the Militia hiding in a stable. Some religious items found on his person gave him away, yet though tortured cruelly he never spoke. After his execution his body was heaved into a barrel of pitch in the Market Square and set ablaze, the Militia ordering the town's people to open their windows so that the "Holy Smoke" might enter the houses and purify the terrified Catholic inhabitants.

Roddy McCorley — As part of a pacification programme hard on the heels of the 1798 rebellion in the North of Ireland, the Crown issued a proclamation offering pardon to any rebel who had not served as an officer. It had the desired effect. Soon after the peasantry had surrendered, the authorities began to deal with their captains. If recorded history has long forgotten the names of those who found their fate on the hanging tree, the balladeers ensured that their names live on in the National Tradition. Late 19th century poet Ethna Carbery, from Ballymena, Co. Antrim, found just such a song about a rebel lieutenant executed on "The Bridge of Toome" on the shores of Lough Neagh, and rewrote it in 1898 to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the rebellion.

The Boys of Wexford — This Robert Dwyer Joyce song captures the "beaten but not broken" attitude of many Irish when looking back at what might have been. The incredible valour of the Wexford insurgents had stunned their opponents in nearly every engagement. Originally dismissed as a rabble-in-arms, the rebels nonetheless time and again managed to defeat trained soldiery but then squandered their advantage when their inexperienced officers failed to exploit their tactical advantage. Ultimately, despite the raw courage of the rebels, the professional military leadership of their opponents won the day for the Crown.

The Ringsend Boatman — This song is set in 1803, after the failed rebellion of that year. This rising was but a last convulsion of the troubles of 1798, and its young leader, Robert Emmett was hung, drawn and quartered in Dublin. Knowing their lives to be marked, his fellow rebels scattered, many to foreign countries. Ringsend was a small maritime village on the south bank of the river Liffey. It was to that place our hero and his love fled to escape to France, the traditional refuge of Irish rebels. I wrote this with songwriter, Pete St. John (The Fields of Athenry, The Rare Auld Times).

Down by The Glenside — My great-grandmother, Brigid Fitzgerald (nee Pearse), a rebelly woman born in Kilrush, Co. Clare, sang this. The chorus refers to 'The bold Fenian men" a 19th century revolutionary society, whose cause, "was a failure." But they kept alive the notion of rebellion, inspiring the rising of 1916. Her father, Patrick Pearse, was a Fenian and boot-maker in Co. Clare. Colonel Vandeleur, local Militia commander, rightly suspected Patrick of rebel sympathies, but nonetheless came to Pearse to have boots made. Sitting next to the workbench with his long legs crossed, he'd swing his leg under the table. The boot-maker was terrified lest the Colonel's swinging leg dislodge the two Fenian muskets strapped underneath the table. On a day in 1870 the Colonel let slip that the Militia would be rounding up suspected Fenians on the morrow. Mindful that his grandfather had been hanged by the Redcoats for rebel activities, Patrick and his family fled Kilrush for the safety of Kilmallock in Co. Limerick. Peadar Kearny, composer of our national anthem, wrote this. Included is a poem, The Mother, by Patrick Pearse (no relation).

Dublin City. 1913 — By 1913 Ireland was marching inexorably down the road to rebellion. The strike and lock-out of that year proved a catalytic, curtain-raising moment in the drama that would unfold three years later. What began as a strike ended as a revolution, for behind the bright facade of the Vice-Regal court lay a city of slavery and the appalling Dublin slums, where the death rate exceeded that of Moscow and Calcutta. This was the domicile of the labouring class, whose sufferings were compounded by their employers, who exacted for a pittance a seventy-hour working week. Too long put upon, they struck back in 1913, calling a general strike. The meetings and demonstrations were proclaimed as unlawful and the crowds were attacked by police. At all hours riots would break out without warning, mobs hurling bricks and bottles at the Royal Irish Constabulary, the latter reacting in savage reprisal. But the suffering and dying would yield them little. After eight months the strikers, broken by the hunger of their wives and children, were forced to sign a pledge renouncing the union. Three years later, all would be "changed, changed utterly."

The Minstrel Boy — Thomas Moore was born in Dublin in 1779. At an early age he displayed great gifts as actor-musician. A college friend awakened his interest in Irish music, soon he was passionately involved in it. His songs portrayed the soul of Ireland, its Joys and sorrows, the ancient myths and laments, the fierce patriotism of its people. His lyric genius, his sense of integrity and the depth of his love of country earned him the title "The Bard of Ireland." I sing Moore's song here with my sister Geraldine and included in the song is an extract from "The Rebel" by Patrick Pearse, poet, philosopher, visionary, teacher and leader of the 1916 rebellion, for which part he was executed in Dublin, May 3rd, 1916.

James Connolly, The Worker's Hero — Written by Pete St. John. Connolly was born in Co. Monaghan and reared in Edinburgh. At 11 years he worked a forty-hour week in a printer's workshop. He was a union organizer in the United States from 1903 to 1910, living in Troy, NY. Confronted with the appalling Dublin slums, the Infant mortality rate and endemic unemployment, he concluded that social amelioration could only come about in the wake of independence. With the members of his union, he formed the Irish Citizen Army, who in the beginning were lackadaisical and always late for parade. Connolly remarked, "I can guarantee the Citizen Army will fight, I just can't guarantee they will be in time for the fight when it takes place." When in 1916 the Irish Citizen Army took its place at the barricades, my uncle Martin Foy was among them. Connolly, along with fifteen other leaders, was executed in May 1916.

A Rare Time for Death in Ireland — This is a prose extract from the playwright Seán O'Casey's remarkable autobiographies. Born in the Dublin slums, O'Casey was a bright intelligence who worked as a railroad labourer and wrote hard-hitting anti-British articles for his union newspaper. He was secretary of the Irish Citizen Army but resigned in a fit of pique, a constant O'Casey condition. He declined to take part in the Easter Rebellion of 1916, considering it gross folly. Although not a physical force rebel he would witness the dramatic events of his troubled times, rebellion becoming the literary well-spring from whence his Abbey Theatre plays flowed; The Shadow Of A Gunman, The Plough And The Stars, Juno And The Paycock. When the Abbey Theatre rejected his play, The Silver Tassie, O'Casey left the country in high dudgeon, never to return.

The Foggy Dew — One of the greatest Irish songs, certainly the best of the many written about 1916. In Dublin that Easter Monday, the clocks and church-bells struck noon, the rebellion-anointed hour. Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army men and women converged on the strategic points they would seize and hold. Patrick Pearse's Volunteers and James Connolly's Citizen Army contingent formed up outside the General Post Office in Sackville Street. Connolly took Pearse's hand, "Thank God, Pearse, we have lived to see this day." The men charged the building, smashed out the windows and barricaded the magnificent Palladian structure. When the green, white and orange flag was raised, the liberation of the world's oldest political prisoner began. The rebellion lasted almost a week. The execution of the sixteen leaders was a grave British miscalculation. The country had been against the rising, but now the people were implacably against the British. The War of Independence, 1918-1921, would finally force them to yield the battlefield to the rebels.

Come Out! You Black & Tans — Since the Great Famine of 1847, Ireland had experienced no such horrors as the ones inflicted upon her in 1920. General Michael Collins, Irish Republican Army commander, grimly remarked; "We shall see which will last longer, the body or the lash." Britain now let loose on Ireland a vicious, blood-thirsty force: The Black & Tans. The name quickly became a synonym for terror. Their orders were to terrorize the Irish into abject surrender. In County Clare they burnt the towns of Ennistymon, Lahinch and Milltown Malbay, then Trim, Co. Meath, Balbriggan, Co. Louth and Mallow, Co. Cork. In Cork city they looted, wrecked and burnt the entire town centre, holding the fire brigade back at gunpoint, then shooting two brothers named Delaney for good measure. They executed fathers, sons and priests out of hand. They killed the Lord Mayor of Cork, Thomas McCurtain, in front of his wife and children. But they forgot that you cannot put an idea up against a wall and kill it.

Kevin Barry — On November 1st, 1920, the British hanged eighteen-year-old Kevin Barry. He was captured when his IRA unit was engaged in a gunfight in Church Street, Dublin. A great protest swept across Ireland when Kevin died, for people thought his hanging an intolerable outrage, for Barry had only done what an Englishman would do given the same provocation, namely, the suppression of his country's liberty by a foreign power. At the end he was in smiling mood. No one could fathom his good humour. His mother said, "Don't you understand, my son is proud to die for Ireland." A sneering British officer asked him, "What can your leaders do for you now?" Kevin replied, "Nothing much, but I can die for them." His mother came on a last visit. During a long awkward moment of silence Kevin began to sing;

"Step together, boldly tread, firm each foot erect each head,

Fixed in front be every glance, forward at the word 'advance,'

Serried files that foes may dread, like the deer on mountain heather,

Left, Right. Left, Right, steady boys, and step together."

He kissed and embraced his mother and she left her son for the last time, trying hard not to break down. When she turned at the cell door for one last look, he was standing at attention, at the salute.

A Nation Once Again — This great song, written by Thomas Davis around 1840, was for a while our unofficial National Anthem. The aspirations expressed therein were partially realized in 1922 when the British left those 26 counties that now constitute our Irish Republic.

Epilogue

The German philosopher Nietzsche warned against staring too long into an abyss, for eventually, he said, it would stare back. Ireland was England's abyss, and Ireland's defiant glare had seldom faltered. The tragic, desperately splendid history, a litany of unparalleled persecution, ended in 1922, and the deciding factor had been courage.

"Let the cultivation of a brave, high spirit, be our great task. It will make of each man's soul an unassailable fortress. Armies may perish, but it resists forever. The body it informs may be crushed, but the spirit in passing breathes on other souls and other hearts are fired to action and the fight goes on to victory."

Terence McSweeney, Lord Mayor of Cork.

Through seven centuries of misery, every generation with immutable stubbornness had resisted the unrelenting oppression, treasuring the remembrances of lost liberty. Outnumbered a hundred to one they had fought with barely a chance, yet not all the Armies of the Empire had been able to crush the spirit of the true patriot men and women. If by now the grass has grown high and wide over the old battlefields, it will never grow over the memory of a thousand lonely scaffolds, for these are the memories that are burned into the Irish consciousness, forever.