|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

"We shall never conquer Ireland while the Bards are there."

A statement insightful, prescient … and four hundred years old. After making it, a furious Queen Elizabeth set about correcting the oversight, ordering her deputies to "hang the harpers wherever found." The shrewd old Queen had learned what the Irish always knew instinctively — that, in the fullness of time, he who has the best ballads wins.

Almost precisely two hundred years ago, Defenders and Unitedmen took to the fields of Ireland in wrath and expectation, yet the lyric and rhyme to which they marched, the songs of 1798, lie scattered still across the Irish consciousness "thick as autumnal leaves." That seminal year defined what Ireland was and what it would become. And the Irish folk-memory — that faithful reflection of the common life of the people — remembers. Indeed, the heroes and villains of that year resonate yet through the Irish consciousness.

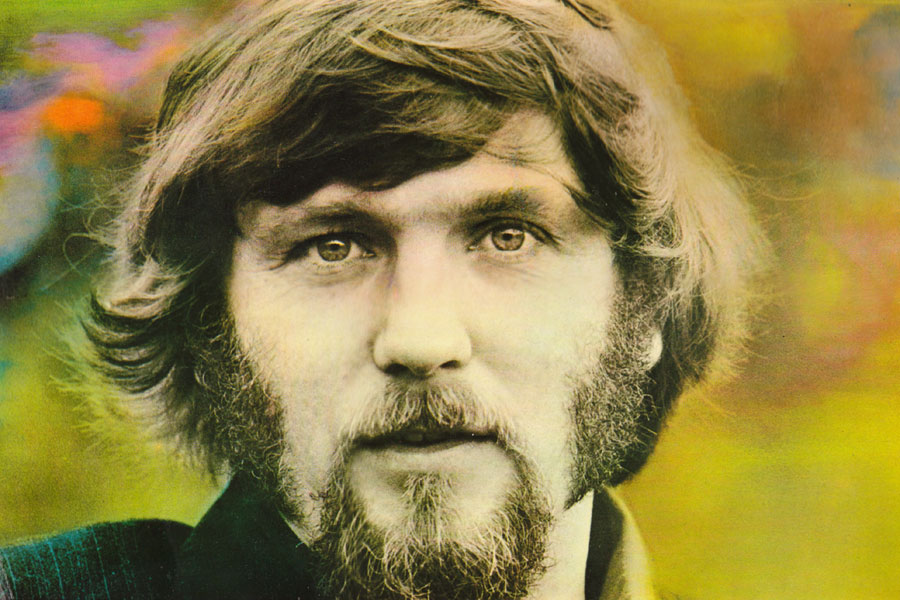

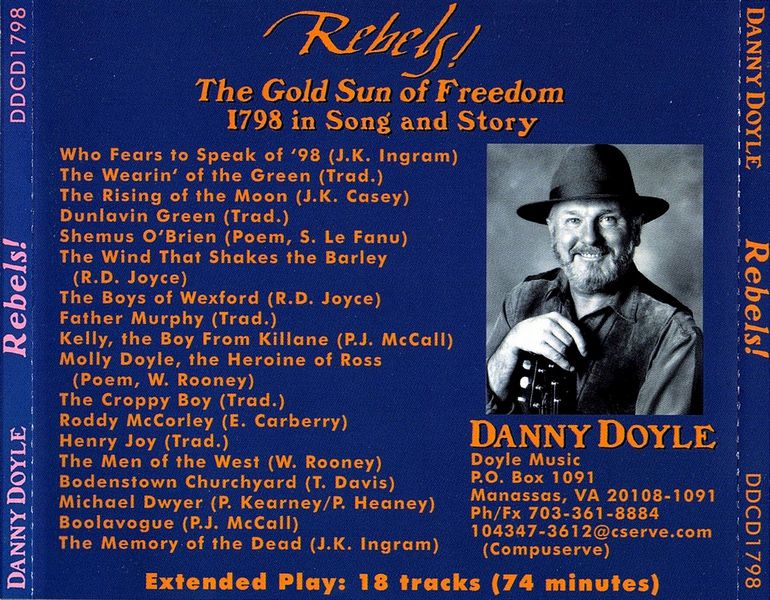

In a concert career that has spanned three decades, Danny Doyle has sung many ballads dealing with the events of 1798. But never quite this way.

This album is much more than a mere collection of songs. Instead, the renowned balladeer has here become the Seánachie, the Irish storyteller with quite a tale to tell. Here, he has woven together the story of the great rebellion of 1798 in song, story, and poetry, and the result is a unique Irish weave with a musical texture all its own.

Danny has long understood that the ballad tradition is both Ireland's Dictionary of National Biography and a sort of Enclyop?dia Hibernia. The ubiquitous balladry tells us what happened in 1798, and sings of those who lived the events, leaving us a legacy of national poem and song that binds us to that past and country by the ballads' "condensed and gem-like history."

Balladry is perhaps better suited than narrative history to explain the driving forces behind events in Irish history — the driving forces sufficiently compelling to send men out with pikes and hay-forks in 1798 … and poets out with rhetoric in 1916. Listen to Danny and you will find that, even if you do not know the what of Irish history, the ballads will invariably tell you the why.

— Terence Folan, author, Blood On The Harp

The Ballads

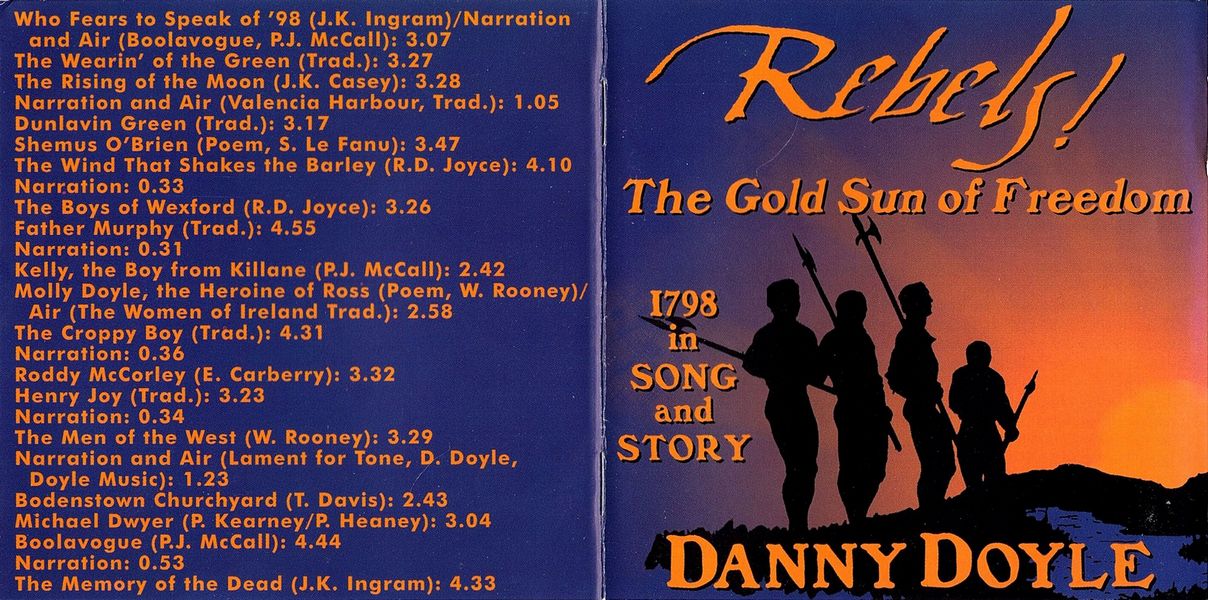

Who Fears To Speak of '98? — If, as in this ballad by John Kells Ingram, the events seem nearer in the singing, it helps explain why the authorities deemed balladeers more dangerous than the fieriest agitators. When this song was first published in 1843, its author was but a lad of twenty. Ingram would later become a professor at Trinity College. Dublin, and president of the Royal Irish Academy.

The Wearin' of the Green — The colour green was adopted in the 1790s by Irish republicans from the French Tree of Liberty, and has for the two hundred years since been the symbol of Irish nationalism. Frank O'Connor said, "this little song … probably by an Ulster Presbyterian and set to what seems to be an adaptation of a Scottish pibroch, is our real national anthem."

The Rising Of The Moon — On the eve of the 1798 rebellion, a tense expectancy arose among the Irish. Many of the common folk, considering they were "guilty" in the eyes of the terrorising authorities, hid pikes and blades in anticipation of the rebellion anointed day. Threescore years afterward, a 14-year-old Co. Longford youth, John Keegan Casey imagined that time when he wrote this song. The young Fenian poet captures the defiant excitement of the period vividly, and this is unquestionably the most widely known of all Irish ballads. Indeed, that proud rhymer of British Imperialism. Rudyard Kipling, told how he heard the song sung by a Himalayan herdsman and his family, as he sheltered in their humble but lofty mountain hut.

Dunlavin Green — As the 1798 rising began in the counties around Dublin, the garrison commander at Dunlavin, Co. Wicklow marched twenty-eight prisoners to the village green. Although these men had taken no part in the risings, they were executed on the spot. The Crown would later regret the reprisal, especially since the slain included men from the remote Glen of Imaal. An infuriated neighbour named Michael Dwyer immediately became a hardened rebel, would fight in the Wexford campaign and afterward, would lead the authorities a merry chase for five long years as leader of a mountain guerrilla band.

Poem: Shemus O'Brien is a fictional rebel, who with the aid of a priest, makes a daring escape from the gallows in '98. This is from a longer poem by the Dublin author Sheridan Le Fanu. Indeed, the subject matter of a triumphant rebel would seem an unlikely one coming from the pen of a man who proudly proclaimed his allegiance to the Crown and to the values of the middle-class Victorian establishment of the mid-19th century.

The Wind that Shakes the Barley — Written by Robert Dwyer Joyce, professor of English Literature at Dublin's Catholic University in the mid-nineteenth century, this caoine serves as both a love song and, more subtly, as a song of resistance. The singer's quandary is the age-old one of potential rebels — how can he part from all he holds dear to march off and sacrifice his life in what is probably a hopeless cause? In this case, a British bullet resolves the dilemma.

The Boys of Wexford — This Robert Dwyer Joyce song captures the "beaten but not broken" attitude of many Irish when looking back at what might have been. The incredible valour of the Wexford insurgents had stunned their opponents in nearly every engagement. Originally dismissed as a rabble-in-arms, the rebels nonetheless time-and-again managed to defeat trained soldiery … and squandered their advantage when their inexperienced officers failed to exploit the tactical situation. Ultimately, despite the raw courage of the rebels, the deadly professionalism and leadership of their opponents made the difference.

Father Murphy — In April 1798, Fr. John Murphy was a simple parish priest enjoining his flock to turn in whatever weaponry they were hoarding to the local authorities. By the end of May, Dublin Castle considered him the most wanted man in Ireland, for he had become a legendary rebel general leading an army of tens of thousands into combat against the Crown. Representative of ballads from that era. this one offers a remarkably accurate chronology of the engagements and battles in which the croppy priest fought that spring and summer.

Kelly, the Boy from Killane — In a time when adequate nutrition was not available to the common folk of Ireland, the tall man was a rarity. Wexfordman John Kelly would probably have stood out, in any case. One eyewitness, spectator to the young giant's courage at the Battle of New Ross, suggested in awe that Kelly displayed "the bravery and heroism of the greatest general of antiquity." The description was written years later when the witness, not normally driven to hyperbole, was himself a decorated colonel in the French service. Kelly, while recuperating from his battle wounds, was betrayed by a neighbour whose life he had saved previously. He was hanged on Wexford Bridge. The song is by Patrick Joseph McCall.

Poem: Molly Doyle, The Heroine of Ross — On the eve of the battle of New Ross, County Wexford, Molly Doyle persuaded her aged father to return home. She promptly took his place in the insurgent ranks and fought with distinction. During the battle, when the rebels ran out of powder and ball, and with English bullets whistling around her, Molly daringly leaped among the dead and wounded redcoats and with a sharp blade cut free their ammunition pouches, flinging them back to her Wexford compatriots. Later, when her exhausted comrades were faltering in battle, Molly rallied the rebels to make yet another assault on the enemy lines. The poem was written by William Rooney to commemorate the centenary of the rising.

The Croppy Boy — In the years before the 1798 rebellion, many among the lower classes began to cut their hair in the cropped style of the French revolutionaries who had so effectively destroyed the French aristocracy. Even before the rebellion, Crown forces often took this vague sign of disaffection as proof that a peasant was a rebel and, in some cases, his short hair became his death warrant. Indeed, to the authorities, the derogatory phrase "mere croppy" became sneeringly synonymous with "simple peasant." This ballad was sung just after the fighting.

Roddy McCorley — As part of canny pacification programme hard on the heels of the Antrim rising, the Crown issued a proclamation offering pardon to any rebel who had not served as an officer. It had the desired effect. Soon after the peasantry had surrendered, the authorities began to deal with their captains. If recorded history has long forgotten the names of those who found their fate on the hanging tree, the balladeers ensured that they live on in the National Tradition. Late 19th-century poet Ethna Carbery found just such a song about a rebel lieutenant executed on the shores of Lough Neagh, and rewrote it into the form with which we are familiar today.

Henry Joy — Henry Joy McCracken was the wealthiest of the United Irishmen, and one of the most dedicated. The industrialist's house in Belfast's Rosemary Lane had long been a centre of Celtic culture (it was there that Edward Bunting transcribed the music from the last convention of Ireland's wandering harpers) when he became one of the founders of the Unitedmen. When the North rose in 1798, McCracken was commander-and-chief of the insurgent forces in Co. Antrim, the only founding member of the United Irishmen to actually take the field. As this ballad tells us, this Gaelic-speaking Church of Ireland rebel leader was publicly executed … for his treason to both Britain and his social class.

The Men of the West — As the centuries passed, the Gaelic language and Ireland's indigenous culture were pushed further into the western reaches of Ireland … leaving a nostalgic yearning among many for a time when Gaelic "heroes walked the land." And, indeed, "when Ireland lay broken and bleeding" after rebellion had been put down savagely in Wexford, the Midlands, and the North, a thrill of excitement ran through rebel Ireland when the "bravest and best" of Mayo peasantry rose in yet another 1798 attempt to win freedom. This ballad was written by William Rooney in honour of those who rose when the French landed in Killala Bay and who joined their continental allies in routing a British army at the battle that has been known ever after as the "Races of Castlebar."

Bodenstown Churchyard — Theobald Wolfe Tone is remembered as a champion of Catholic rights, as one of the original founders of the United Irishmen, the man who persuaded the French Directorate to send troops to Ireland, and who was afterward executed for his trouble. The Irish consciousness remembers that this young Protestant lawyer was indefatigable in his activity for an Irish republic. The Dubliner gave up everything for his objective — the practise of law, the respect of his upper middle-class peers, the comfort of family, even his very life. Consequently, Wolfe Tone stands at the head of the pantheon of Irish martyrs, and his Co. Kildare gravesite is hallowed by those to whom The Republic would after become a watchword. This hauntingly beautiful ballad was written by Thomas Davis, considered the finest of Ireland's rebel poets.

Michael Dwyer — This will-of-the-wisp guerrilla fighter was a painful thorn in the side of the Crown, especially in the dark days after the 1798 rising, when, for five years he led his defiant rebel band through the trackless hills of Wicklow. Dwyer always struck suddenly, and as swiftly disappeared into the welcoming mountains. Indeed, he narrowly eluded capture on numerous occasions and his daring escapades gave a glimmer of hope to an Ireland firmly under the heel of the victor. In 1803, still at large, he was in the thick of the planning for Robert Emmet's rebellion. Having scant success tracking Dwyer, the Crown finally built a road through the Wicklow Mountains, stationing garrisons in the glens. The mountain route is still called the "Military Road." The ballad is by Peadar Kearney and Paddy Heaney.

Boolavogue — Perhaps the most powerful of all the songs of The Ninety-Eight, this achingly beautiful late 19th-century ballad by Patrick Joseph McCall was based on the lyrics of one written at the time of the rebellion. Typical of the "chronological ballads" of the era, this — one of the most vocally demanding songs in all of Irish music — tells the story of Fr. John Murphy from the action at The Harrow to his ultimate fate at Tullow.

Memory Of The Dead — All the many ballads of 1798, in one way or another, do what John Kells Ingram does in this one — they ask us to remember. Yet, while countries all over the world glory in the memory of their Bolivars, Garibaldis and Washingtons, who were willing to risk their very lives to give birth to the sovereignty they enjoy today, Official Ireland seems, in these times, strangely reluctant to celebrate her patriots. In a time when what actually happened in the past is often sacrificed on the altar of a modern political or academic agenda, it may just be useful to occasionally ask such questions as, "Who fears to speak of 1798?" … and, perhaps, why.

Terence Folan, author, Blood On The Harp