|

|

|

|

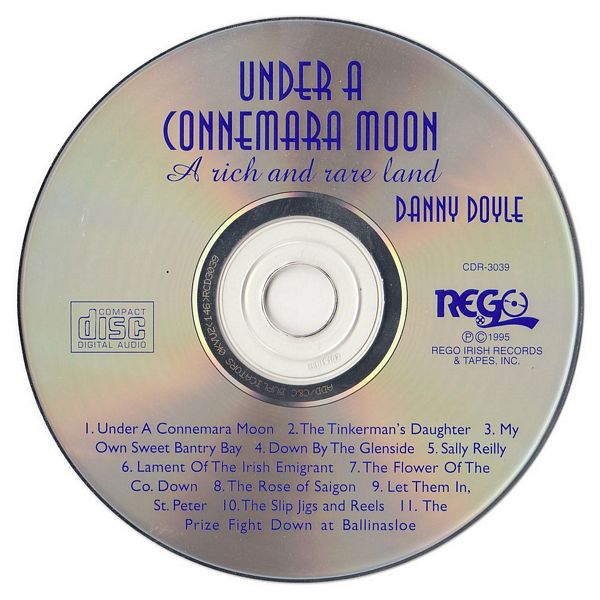

Sleeve Notes

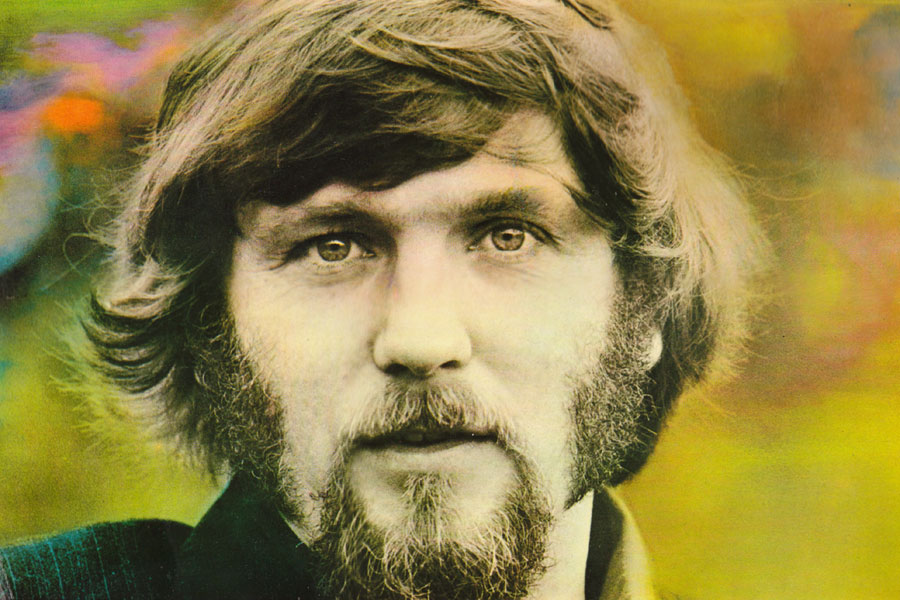

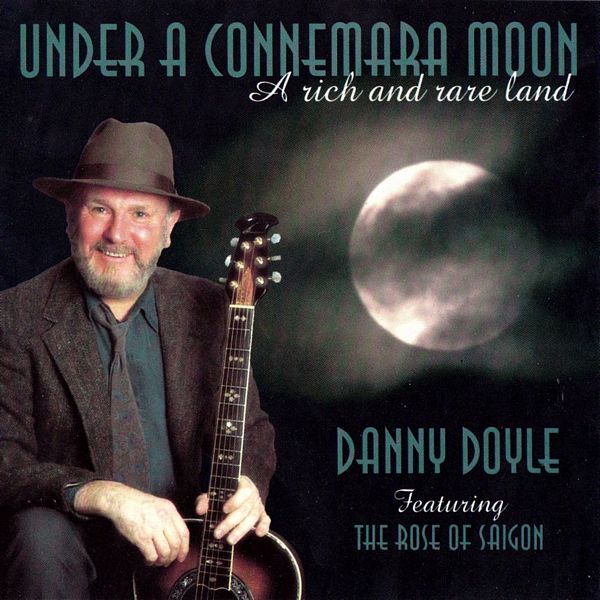

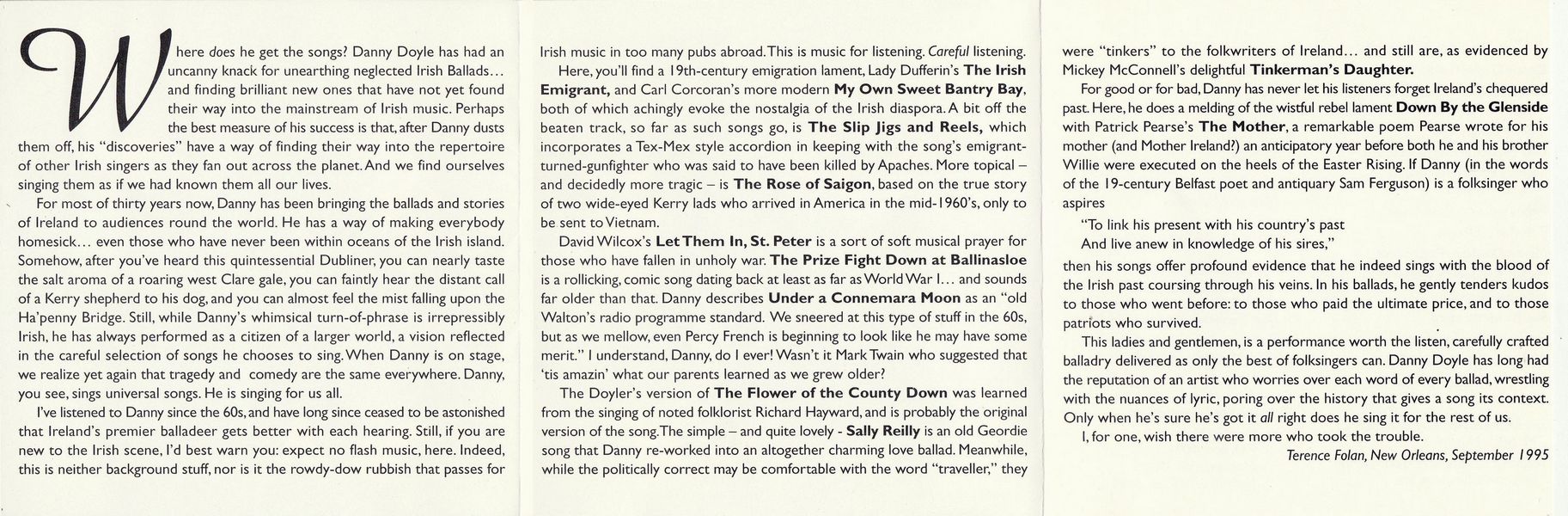

Where does he get the songs? Danny Doyle has had an uncanny knack for unearthing neglected Irish Ballads … and finding brilliant new ones that have not yet found their way into the mainstream of Irish music. Perhaps the best measure of his success is that, after Danny dusts them off, his "discoveries" have a way of finding their way into the repertoire of other Irish singers as they fan out across the planet. And we find ourselves singing them as if we had known them all our lives.

For most of thirty years now, Danny has been bringing the ballads and stories of Ireland to audiences round the world. He has a way of making everybody homesick … even those who have never been within oceans of the Irish island. Somehow, after you've heard this quintessential Dubliner, you can nearly taste the salt aroma of a roaring west Clare gale, you can faintly hear the distant call of a Kerry shepherd to his dog, and you can almost feel the mist falling upon the Ha'penny Bridge. Still, while Danny's whimsical turn of phrase is irrepressibly Irish, he has always performed as a citizen of a larger world, a vision reflected in the careful selection of songs he chooses to sing. When Danny is on stage, we realize yet again that tragedy and comedy are the same everywhere. Danny, you see, sings universal songs. He is singing for us all.

I've listened to Danny since the 60s, and have long since ceased to be astonished that Ireland's premier balladeer gets better with each hearing. Still, if you are new to the Irish scene, I'd best warn you: expect no flash music, here. Indeed, this neither background stuff, nor is it the rowdy-dow rubbish that passes for

Irish music in too many pubs abroad. This music for listening. Careful listening.

Here, you'll find a 19th-century emigration lament, Lady Dufferin's The Irish Emigrant, and Carl Corcoran's more modern My Own Sweet Bantry Bay, both of which achingly evoke the nostalgia of the Irish diaspora. A bit off the beaten track, so far as such songs go, is The Slip Jigs and Reels, which incorporates a Tex-Mex style accordion in keeping with the song's emigrant-turned-gun fighter who was said to have been killed by Apaches. More topical - and decidedly more tragic - is The Rose of Saigon, based on the true story of two wide-eyed Kerry lads who arrived in America in the mid-1960's, only to be sent to Vietnam.

David Wilcox's Let Them In, St. Peter is a sort of soft musical prayer for those who have fallen in unholy war. The Prize Fight Down at Ballinasloe is a rollicking, comic song dating back at least as far as World War I … and sounds far older than that. Danny describes Under a Connemara Moon as an "old Walton's radio programme standard. We sneered at this type of stuff in the 60s, but as we mellow, even Percy French is beginning to look like he may have some merit." I understand, Danny, do I ever! Wasn't it Mark Twain who suggested that 'tis amazin' what our parents learned as we grew older?

The Doyler's version of The Flower of the County Down was learned from the singing of noted folklorist Richard Hayward, and is probably the original version of the song. The simple - and quite lovely - Sally Reilly is an old Geordie song that Danny re-worked into an altogether charming love ballad. Meanwhile, while the politically correct may be comfortable with the word "traveller," they were "tinkers" to the folk writers of Ireland … and still are, as evidenced by Mickey McConnell's delightful Tinkerman's Daughter.

For good or for bad, Danny has never let his listeners forget Ireland's chequered past. Here, he does a melding of the wistful rebel lament Down By the Glenside with Patrick Pearse's The Mother, a remarkable poem Pearse wrote for his mother (and Mother Ireland?) an anticipatory year before both he and his brother Willie were executed on the heels of the Easter Rising. If Danny (in the words of the 19-century Belfast poet and antiquary Sam Ferguson) is a folk singer who aspires

"To link his present with his country's past

And live anew in knowledge of his sires,"

then his songs offer profound evidence that he indeed sings with the blood of the Irish past coursing through his veins. In his ballads, he gently tenders kudos to those who went before: to those who paid the ultimate price, and to those patriots who survived.

This ladies and gentlemen, is a performance worth the listen, carefully crafted balladry delivered as only the best of folk singers can. Danny Doyle has long had the reputation of an artist who worries over each word of every ballad, wrestling with the nuances of lyric, poring over the history that gives a song its context. Only when he's sure he's got it all right does he sing it for the rest of us.

I, for one, wish there were more who took the trouble.

Terence Folan, New Orleans, September 1995