|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

At the origin of Alan Stivell, the determining fact was the making of a Celtic harp by his father Jord Cochevelou, in 1952-1953. Alan's love at first sight for this harp had multiple consequences:

But between the return to the sources and progressive-folk, between the Celtic harp and Pop-Plinn, there is the time of adolescence when Alan Cochevelou, abandoning Latin themes, began to listen to traditional music that had fortunately survived in Brittany: bombarde, biniou, dances, competitions (champion of Brittany several times), festou-noz, Breton balls. His passion for Celtic civilisation led him to immerse himself in his father's library; Ancient history, mythology, history of Brittany, comparative study of Celtic languages, Celtic certificate, pictorial arts and, of course, study of the Breton language. Far from being limited to a love of ancient things, Alan, at a very young age, was passionate about science fiction, which for someone who knows Celtic mythology is not contradictory and helps to understand the electronic forms of Stivell's music. It is also not surprising that, having deeply hated pop music until the end of the 1950s, he welcomed the electric guitar and rock as saviours.

From that time on, Alan Stivell's approach was no longer built solely on feelings but also on lucid ideas.

The main idea was to make the Celts rediscover their own culture, ignored by the official school. And, if possible, to make this civilization known to the whole world.

Why?

Stivell does not consider it superior but it is the culture of his country: Brittany, the culture of peoples who have long been oppressed, the Celts. And when you fight for a people, you fight for all the little ones of the earth.

Alan Stivell, a pure internationalist, is for the destruction of borders, which has as a corollary the end of the domination of certain nations over other nations. If he wants Celtic civilization to survive, it is so that it can exchange ideas with the rest of the world and thus contribute its stone to the universal edifice. A culture is a certain angle from which to look at the universe, its destruction is therefore a catastrophe for humanity.

Stivell deeply believes that the Celtic contribution would be very positive in the construction of a new world. A world of men who are equal but not similar, free but not selfish, where advanced technology could reduce working time to one day a week. A world based on the spirit, not on matter, a world where man would remarry with nature, a world where women would be the true equals of men, a possible world seen by the ancient Celts and destroyed by the imperialist madness of the Roman legions.

Music

Alan Stivell's approach is therefore based on the desire to safeguard his Breton and Celtic identity by fighting not against any foreign influence but against any imitation. For this, the deep rooting that he has carried out was a necessity.

In addition, he wants to transcend the passing forms taken by Celtic music and only highlight what belongs timelessly and specifically to the Celts. Consequently, he is very purist when it comes to ethnic music — but not when it comes to so-called traditional music, in fact popular music of the last centuries — and this partly explains why he uses an instrument like the electric guitar, instruments having no nationality and man should not be possessed by his instruments.

For Stivell, the search for all possible fields of expression is very important: "A Celt must be able to make Celtic music as well with a saucepan as with a moog-synthetizer". Alan would like to create popular music after the year 2000.

The important thing in this evolution is that old forms of expression survive. A new experience does not make past experiences out of fashion but on the contrary adds to them. This is why Stivell loves to make the bagpipes and the electric organ resonate together. "Musical evolution is not vertical but horizontal". A Breton air with a large orchestra is not superior to an a cappella song, it is simply something else.

His need for new musical experiences must be understood as the search for a sincere and total expression. He refuses to hide a part of himself and therefore cannot, driving a car, lighting his house with electricity, confine himself to musical forms belonging to pre-industrial society.

This total expression probably explains the popularity of his music: people of different origins and education, rockers, classical music lovers, lovers of traditional music, pop avant-garde, farmers and employees, intellectuals, musicologists and students, all find themselves in Stivell.

Tomorrow Stivell?

His ambition is quite simply to open the world to Celtic music. Very simple and very shy, he is also extremely persevering …

The major stages of this opening to the world were:

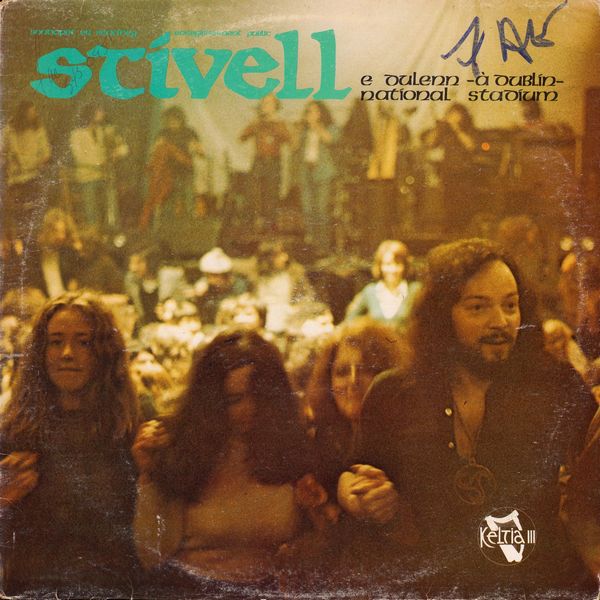

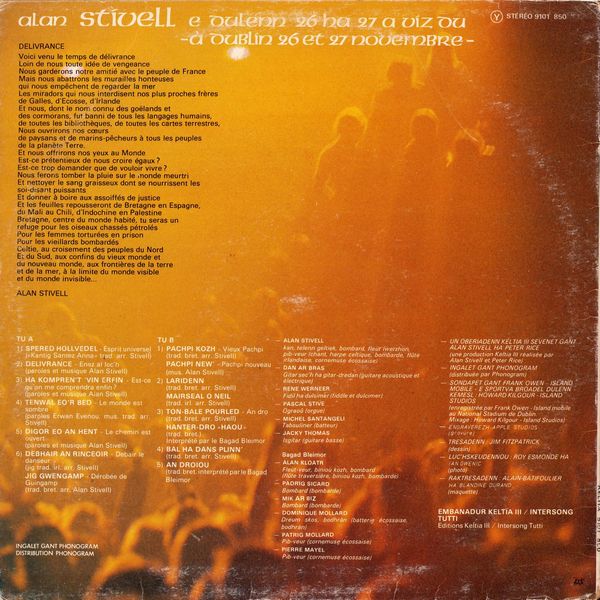

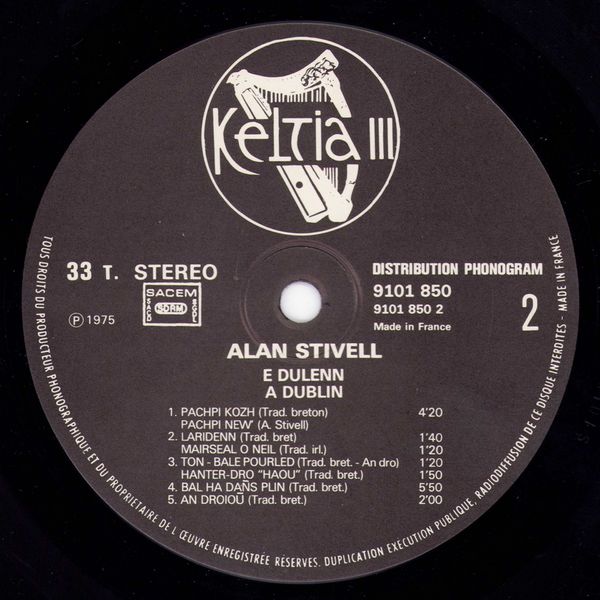

— contract with Philips in August 1967 — concert at the Olympia in February 1972 — three weeks at Bobino in February 1973 — Breton tour under a marquee in May 1973 — National Stadium in Dublin in November 1973 — Elizabeth Hall in London in December 1973 — Place des Arts in Montreal and Hunter College in New York in April 1974 — November 1974 "live" recording in Dublin at Keltia III productions.

Original French translated via Google Translate.