|

|

|

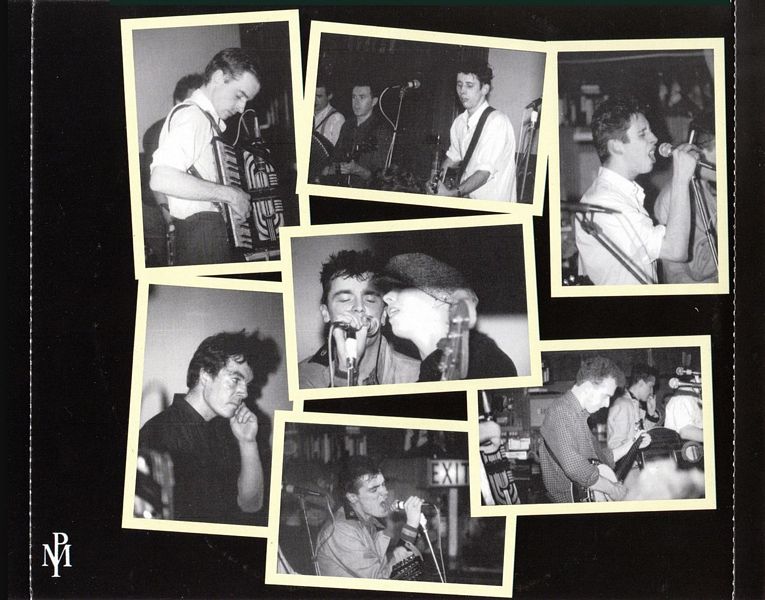

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

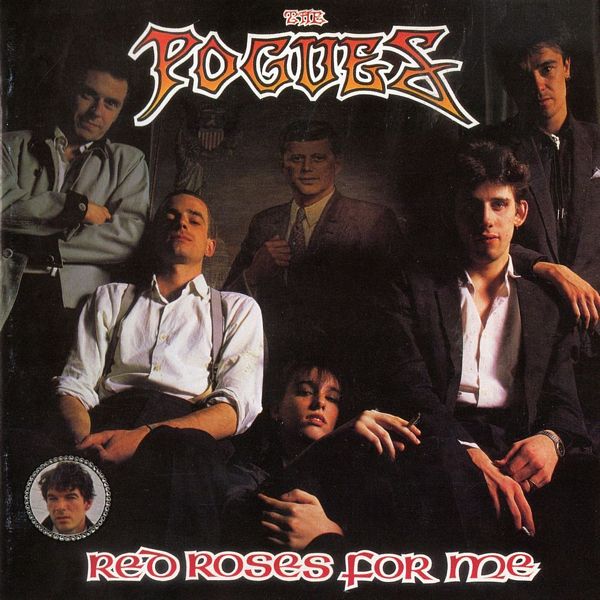

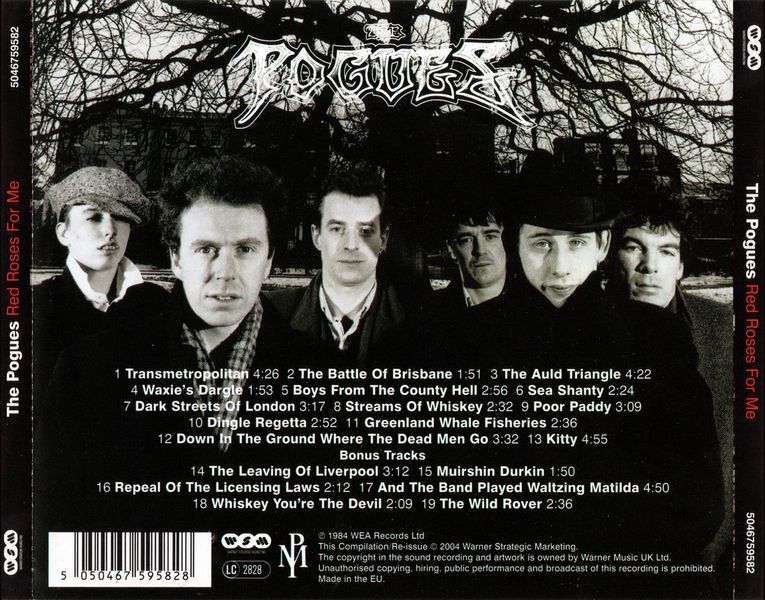

The earliest Pogues relic I hold in my head isn't a piece of music, but is instead an image from a scrap of super-8 film shot by the ubiquitous Don Letts in the mid to late-seventies. It's a pre-Pogues image of the young Shane MacGowan, wearing a shirt cut from the Union-Jack, and pogoing wildly in a gritty London punk club. I guess Shane may have already been in a band, the Nips, along with future Pogue James Fearnley. A little later Shane, James, Spider Stacy and Jem Finer formed Pogue Mahone. This is the group that would become the Pogues: definitely one of the most soulful rock bands Britain has ever produced. But the Pogues aren't just a punk band, or a soul group, or an "Irish" band rooted in a folk tradition. They're all those things and a hell of a lot more. The Pogues made ancient songs sound new, and new songs sound somehow ancient. I don't think they were even concerned with where their inspirations came from, but instead were driven by where their own very particular musical flow could carry them. For me, and all Pogues fans, that music has taken us to so many places — darkened back streets of London, old factory towns, cotton fields, summer in Siam, New York City engulfed in snow and melancholy; poetic, cinematic voyages into Irish social history, or deep inside "a pair of Brown eyes" c ghost of a smile" … Hats off to all the Pogues — for music the color of tobacco smoke and alcohol, sad dreams, underdogs and lost love. Their deep connection to Irish music isn't a reinvention, exactly, but more like an uncontrollable channelling and celebration of its resilience. I love the Pogues. I always will. They may have disbanded some years ago, but you couldn't kill the soul of their music with a fuckin' shovel.

Jim Jarmusch

2004 NYC

I guess it must have been the same for the people who watched The Beatles at The Cavern or some dive in Hamburg, or for the disgruntled pub rockers and hippies who saw The Sex Pistols and The Clash make their first advances in the punk rock wars.

I even met a guy in Nashville recently who spent his teenage years in Shreveport Louisiana going to see Elvis Presley every week at the Louisiana Hayride.

This was before the truck driver had become the King of rock n roll.

"I didn't know what I was seeing," the guy who regularly saw the young Elvis, told me.

When I heard that, I didn't feel so bad. I had seen future Pogue Mahone and later Pogues front men Shane MacGowan and Spider Stacy rehearse a classic 2-man move.

It was on the upstairs of a double-decker bus in Kings Cross on a raucous Saturday night in 1983.

And part of me thought it was just 2 drunk men on a bus.

There was Spider whistling like King Billy O, tootling on his tin whistle like nobody's business. Can't recall the tune by name but I can say it was played so hard and strong that the veins of his temples bulged out, fit to burst. And there locked in close beside him — was a long and scrawny figure, bug eyed and — back then at least — big toothed. He was hollering some Mad Celtic Curse and, Ladies and Gentlemen raise your glasses please, his full given name was Shane Patrick Lysaght MacGowan.

And let's be honest — I did think it sounded good at the time, who wouldn't have? What could have sounded better on a dreary night in the big smoke??

But though swept up in the moment there was a part of me that said, "Remember — this is just two drunk men on a bus."

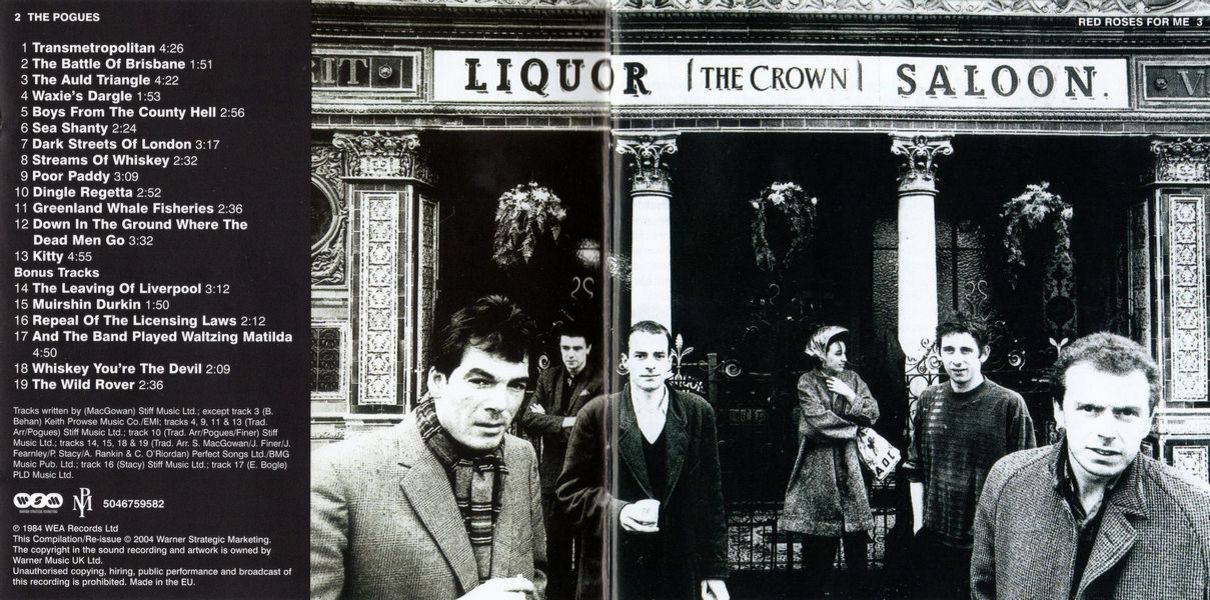

Ah but then (and even now) there was time enough for sober thoughts. Even around 20 years after it came into the world you can hear this record and know the truth. And the truth is in the music, it belts out from the opening 'Transmetropolitan' a steam piston powered Irish air come to wreak havoc and vengeance on the big English city.

It takes you through the scarred and frantic beauty of 'Streams Of Whiskey' where novelist and IRA man Brendan Behan is ready to help you along. It howls through the foreboding 'Dark Streets Of London' where the obscene spectacle of the contemporary city is unleashed in a searing pop moment.

As an independently released single this was the first song Pogue Mahone released on record. Before they had the Mahone, or the "my arse", part of their Irish name removed and became The Pogues. Whatever you want to call them, their inspired and impassioned reinvention of Behan's The Auld Triangle' was a thing of stark beauty. While the woebegone, real life history tale they don't teach in school — 'Poor Paddy' came fuelled with vampire and banshee wails, plus 40 shades of fire and thunder.

And the truth, which I couldn't really have known at the time, was that these two gentlemen were musicians come magicians, stirring up ghosts and wired to the moon energy. It was energy that lay waiting to be reactivated as London slumbered and slouched towards the end of the century.

Of the songs Shane sang some he wrote and some he heard in family settings in Dagenham or Tipperary or at gatherings elsewhere. Or in a country pub. On a jukebox or a relatives record player.

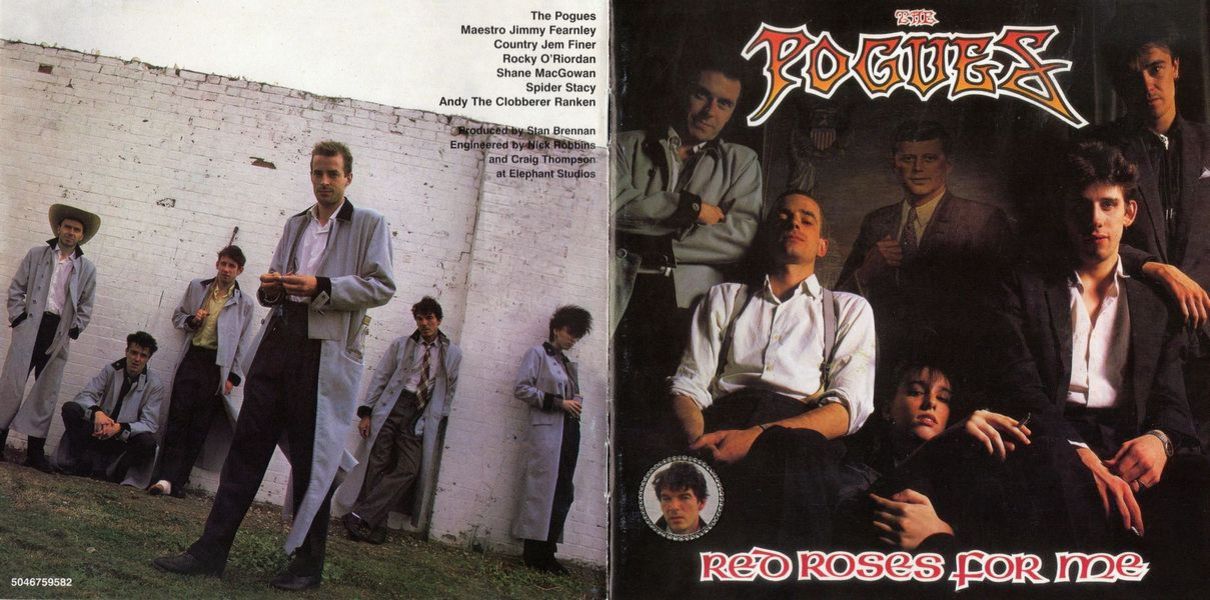

Anyway with these songs MacGowan recreated the city as a place sick with bad memories or a place where the damned dreamed of walking in streets of paradise. The genius of The Pogues was their ability to bring Shane's vision life. So glasses once again for this album's other stars Maestro James Fearnley, Cait "Rocky" O'Riordan, "Country" Jem Finer and Andrew "The Cloberrer" Ranken.

What they came up with was Anglo Celtic music as sensational as when Van Morrison stamped his mystic mush on the R&B template in the '60s. Or Johnny Rotten taunted a sleepy nation with his antichrist status and songs for a rotting monarchy back in the 1970s.

Ahh yes Johnny and Van both friends of Shane two more old Irish greats. And on the strength of this brilliant record alone — now enhanced with extra tracks and personal reminiscence from a man who was almost there — I'd have to put The Pogues alongside em.

So with hindsight those two drunks on the bus with the tin whistle and the bottles and cans how would I rate it? It would have to be right up there in my top "new rock n roll hybrid being born" moments of all time.

So y'see it's like this — you can be right there, somewhere near the epicentre of an unfolding musical revolution, and not even know what is going on.

Feel free to try this at home.

As with many good modern rock 'n' roll stories this one, for a time at least, found its home in a Hi Fidelity style Record shop. Rocks Off Record shop in Flanway Street London W1, during 1983, was a special place, run by a man from the city of my birth, Belfast.

With rare, precious and sometimes ridiculously under priced vinyl on sale the shop was a veritable treasure trove tucked in behind the more standard fare of The Virgin Megastore. This was a place where dreams could be planted and grow. And the man from Belfast, storeowner Stan Brennan, would give me regular updates on an ongoing project close to his heart.

The project involved the wild-eyed heavy drinking Shane MacGowan, the guy who sometimes served time behind Stan's counter.

It seemed Shane was bit irregular in his attendance. This created a, possibly unfair, impression that his sole interest wasn't just in making money. He wanted to do that, for sure, but sometimes his hectic life dictated he had to be elsewhere.

There was also the lure of liveners in the various pubs in the vicinity.

And just in case you think drink only maketh the man it's a fair bet the shop's wares brought occasional added inspiration to his already teeming musical imagination. An imagination nurtured both in the Irish traditional (fiddles, Guinness) and English modern (gobbing, Sex Pistols) schools.

Shane, Stan would tell me, was in the process of putting together a band that was set to rock the world. In a way that the world had never been rocked before.

Since I'd got to know him Stan had introduced me to some of the greatest music ever recorded anywhere or at anytime. But to my NME-tutored cynical musical journalist self his assurance of Shane's future brilliance seemed a bit unlikely.

I'd first encountered MacGowan at a safe distance a few years before. There he was, still known as his punk era moniker Shane O'Hooligan, breathing fumes of alcohol and vengeance after a liquid lunch, just another very disgruntled reader, albeit with minor celebrity, in the reception area of NME's Carnaby Street headquarters.

His mission then was to have an intimate heart to heart with a fellow journalist. The scribbler in question had the temerity to be less than ecstatic about The Nips latest release, 'Gabrielle'. Shane was then fronting The Nips, a band that, in a pattern that would continue with the former Pogue Mahone, had been forced to shorten their name from the less broadcast friendly The Nipple Erectors.

The Nips had the support of luminaries such as Paul Weller and Shane had early punk notoriety. Shane then was not the man of song writing letters he has since become in any rational musical mindset. Back then Shane was the Oh Bondage fanzine writer who had his ear all bloodied by Kate Modette at an early Clash gig.

The Nips, despite providing a home for future Pogue Mahone/Pogues maestro James Fearnley, disbanded without making a significant dent on the face of rock.

And so Shane had become something of an also ran in the minds of many pundits.

Certainly it was hard to see where he could fit in because in many ways MacGowan was an old soul, haunted by more demons than most. The post punk strait jacket may have come off, and rock's revolution had taken several interesting twists but the early 80s were grim times for righteously messed up, unrepentant rebels like Shane Patrick.

His star-crossed past had seen him in a mental home and a top English public school, in many a dingy tavern and over the hills and far away.

And back on that moving bus, coming just up to the Scala Picture house in Kings Cross sometime in 1983. I remember after the short performance the driver moved up a gear and sped through the lights. At that moment our two heroes — Spider and Shane — rose up, and almost just as soon as they had they fell together in a heap of drink and curses and giggles. This was a snapshot in time from many nights of similar mayhem and added debauchery.

Thought one — it was frankly a miracle The Pogues ever got into the recording studio in the first place. Thought two — we are blessed that when they got there they gave us so much insight and innovation.

Innovation? Yes yes yes where else In pop and rock and folk history are you going to hear anything like the spook classic 'Down In The Ground Where The Dead Men Go'? With its Velvets like opening discord to the blooding jousting bacchanal this is a stunning apparition of mortality from the blackly comic Shane and Spider double act.

Was any debut album ever so sunk in the depths of death as this one? Casually entering the afterworld with the very real scent of decay in the air, beckoning to hellhounds. Bob Dylan's self titled debut perhaps, Van Morrison's post Them solo piece 'T B Sheets' of course. Although MacGowan is as likely to have taken Liam Clancy's classic 1965 Vanguard solo album as his artistic template.

Back on that bus, Shane and Spider had got up for a reason; it was round these parts that the men — and woman — who would make this record got together. It's cleaned up a bit now in anticipation of taking its new place in the new Trans European London. But Kings Cross in the early 80s was a kind of inland urban port in the island state of the metropolis. In short the dumping ground — in rightist sociologist terms — for the dregs of Thatcher's Great Unwashed. Nailed to the cross of Kings. The place where liars scumbags, junkies, backbiters, syndicators dreamers, lost souls and alcoholics — and some REALLY nasty sorts — hung out.

So thank goodness for squat culture and The Pogues, you wouldn't have had one without the other. Kings Cross was just one of those places where people from disparate backgrounds could meet rehearse and make connections with each other.

They may all ultimately all have had other plans and things to do but they realised that together they could make something happen. What it was was something new, something different, a real life art constructed from their surroundings.

It flourished when matched with songs as potent and insightful as 'Kitty'. Sung by MacGowan's mum in, his childhood its wartime storyline now had vivid new relevance in the wake of the Falklands conflict.

From 'Kitty' to the solemn wake and bitter anger of Eric Bogle's beautiful 'And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda', The Pogues could do sensitive atmospherics with feeling and aplomb.

They could also rip the roof off the joint, playing at a furious tilt, which meant — contrary to their pisshead image — there were no shirkers in the house of Pogue.

MacGowan had managed to find what it took to make his musical paradise come true. And here it was The Sex Pistols setting fire to the Chieftains, a suitably augmented Clash roaring along beside The Dubliners.

How did they do it and how did they manage to keep it at such a furious pitch and pace for as long as they did? Yet on they went. They picked themselves up off the top deck. They lost and gained a few along the way but went to make even more fantastic and life changing records after this.

But there'll always be something special about The Pogues opening bouquet. With hindsight its full blooming glory can now be easily seen — and heard. Now with such added essentials as 'Muirshin Duirkin' and The Dubliners foot stomper 'Wild Rover' — one of the great debut albums just got even greater.

Gavin Martin

PS — Stan, how could I ever have doubted you?