|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

Ys — In tribute to Jef Ar Penven.

Improvisation/Evocation of the legend of the city of Ys (capital of the Kingdom of Cornwall in Armorica in the 5th century) which was swallowed up by the waves, as punishment for the sin which reigned in the city. Eternal theme (Atlantis, Flood) which means that material progress is heading towards catastrophe without moral progress, without a growing respect of man for man.

Theme that I took up in my song "Reflections".

Certain new techniques, such as the one inspired by the "Picking" of the American guitar, are deliberately used to accentuate the universal character of the legend.

Marv Pontkalleg — A very classic arrangement of Breton music.

It is taken from a song from the Barzaz Breiz (epic/collection of popular songs which provoked boundless admiration from George Sand) on the conspiracy of Pontkalleg and the Breton Brothers who were beheaded in 1720 for having attempted to re-apply the clauses of the Brittany-France Union Treaty (1532) guaranteeing the autonomy of Brittany within the Kingdom.

Extraits De Manuscrits Gallois [Extracts From Welsh Manuscripts]:

Ap Huw (Profiad y Botum) and Penllyn (Llywelyn ap Ifan ab y Gof).

Manuscripts from the 17th century transcribing (in an original writing deciphered by A. Dolmetsch) sonatas for bardic harp transmitted orally since the High Middle Ages. Scholarly music, sometimes figurative, showing certain links with Piobaireachd (classical Scottish bagpipe music) and above all using many of the resources of modern harmony!

Eliz Iza — Modern arrangement of a folk song from the Breton mountains.

In homage to the Goadec sisters, my favorite singers.

Gaeltacht — In tribute to Sean Ó Riada

Travel through the Gaelic countries (Ireland, Scotland, Isle of Man).

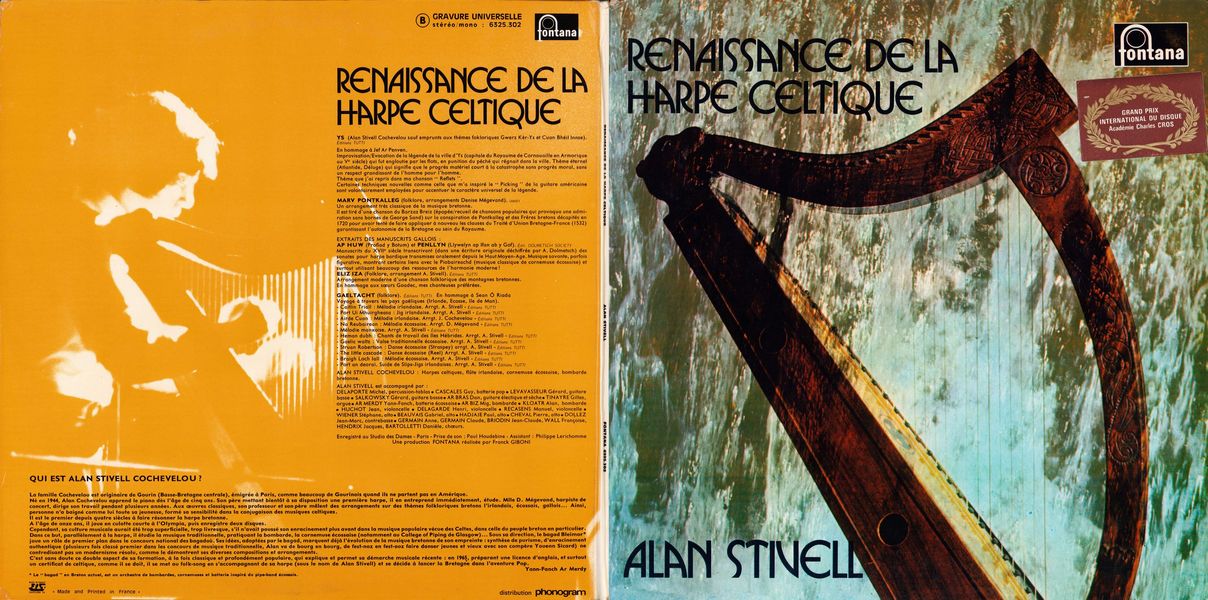

Who Is Alan Stivell Cochevelou?

The Cochevelou family is originally from Gourin (central Lower Brittany), emigrated to Paris, like many Gourinois when they do not go to America.

Born in 1944, Alan Cochevelou learned the piano at the age of five. His father soon placed his first harp at his disposal, and he immediately began studying it. Miss D. Mégevand, concert harpist, directed his work for several years. With classical works, his teacher and his father mix arrangements on folkloric themes from Breton, Irish, Scottish, Welsh … Thus, no one has spent his entire youth like him, trained his sensitivity in the combination of Celtic music.

He is the first in four centuries to sound the Breton harp.

At the age of eleven, he played in short pants at the Olympia, then recorded two records.

However, his musical culture would have been too superficial, too bookish, if he had not pushed his roots further into the popular music experienced by the Celts, and that of the Breton people in particular. For this purpose, alongside the harp, he studied traditional music, practicing the bombarde, the Scottish bagpipes (notably at the College of Piping in Glasgow) … Under his direction, the bagad Bleimor * played a leading role in the national bagadù competition. His ideas, adopted by the bagad, already mark the evolution of Breton music: a synthesis of purism, of authentic roots (several times ranked first in traditional music competitions, Alan goes from town to town, from fest-noz to fest-noz making young and old dance with his friend Youenn Sicard) not contradicting a resolute modernism, as demonstrated by his various compositions and arrangements.

It is undoubtedly this double aspect of his training, both classical and profoundly popular, which explains and allows his recent musical approach: in 1965, preparing for a degree in English, and above all a certificate in Celtic, as it should be , he started playing folk songs, accompanying himself on his harp (under the name Alan Stivell) and decided to launch Brittany into the Pop adventure.

Yann-Fanch Ar Merdy

* The "bagad" in current Breton, is an orchestra of bombardes, bagpipes and drums inspired by the Scottish pipe band.

The Orign

The Primitive Harp — The primitive harp (which is currently found in Africa) was widespread throughout the world. It is the simplest instrument in principle (the bow and the resonance box, a few strings of braided fibers or horsehair), but also the most subtle, the oldest — Sumerian harp from the Bismaya vase 3,000 years old BC, Nebel of Egypt, Saun of India, Assyrian, Persian (with box at the top), Arab, Lydian, Chinese, Malay harps … Only the Greco-Latin civilization disdained it and preferred the lyre or the gyther. The so-called "Indian" or "South American" harp was brought to America by the Spaniards (it is, like the classical harp, a "descendant of Celtic harps").

The Irish Harp — It has been suggested that the primitive harp reached the Celts transported from the Mediterranean by Phoenician sailors. In fact, it could very well have originated in Celtia, independently of any importation ["invented by Idris", one of the three primitive bards of the Isle of Brittany], as well as in China or Malaysia. What is beyond doubt is that it was the Irish who made the slender and rudimentary instrument, the harp that all the authors of the Middle Ages celebrated for its power, its melodious timbre (which they considered higher than that of all known stringed instruments).

This, thanks to the addition of a front column which allows the ropes to be multiplied and tightened further. The Celtic origin of the Western harp could also be attested by the fact that only Celtic languages have specific words to designate it: - Clarsaich in Irish and Scottish Gaelic, Telyn in Welsh, Telenn in Breton. The first certain representation of the Celtic harp is quite late: on a cross in the Church of Ullard near Kilkenny (830 AD) but it probably existed a long time before, because this harp is of a very evolved.

The oldest specimen in our possession, the harp of Brian Boru (Trinity College), dates from the 13th century. This bardic harp, 75 cm high, carries around thirty brass strings.

The harp was greatly cultivated and appreciated in Ireland and the excellence of its musicians recognized by all from the 12th to the 17th century.

The study of this instrument began at the age of 10. It was only at the age of 18 that one could be considered a professional. The harpist must have been a master in three musical genres: the "Suantraidhe" which no one can hear without falling asleep in a delicious sleep, the "Goltraidhe" which no one can hear without bursting into tears, the "Geantraidhe" which no one can hear without bursting out laughing.

All we know about the ancient technique is that it was played with cut nails, the execution was generally delicate and very ornamented. The style was rich, light, fast: high-pitched arpeggios were often superimposed on fourth and fifth chords. There were few men or women of quality who did not know how to play the harp. The harpist was a person of high rank. "Three things elusive by way of justice," says a bardic triad: "the book, the harp, and the sword." (Irreplaceable pledges of his freedom).

The harp seemed, on several occasions, ready to disappear, hunted by the English occupiers, notably Cromwell who had a large number of them destroyed. It was a subversive instrument exalting national sentiment. Its use in public was increasingly confined to the blind and beggars. However, in the 18th century there were still quite a few popular harpers. The arrival of the harpsichord and then the piano accentuated the decline of the instrument which had begun with the disappearance of the national aristocracy. At the beginning of the 19th century, a burst of favor gave birth to the Egan harp which is at the origin of the current Irish harp with gut and then nylon strings.

But the old tradition had died with O'Daly and O'Carolan (who was already quite influenced by Italian classical music), a new awakening in 1900, finally the Irish Republic and especially the last twenty years have given birth to many harpists and companies are currently flourishing.

In Scotland And Wales — From the 5th century, Irish missionaries who came to evangelize the Island of Brittany had the habit of accompanying their psalms with a small harp. Scotland and Wales competed in imitating Irish music. The Scottish harp was identical to the Irish harp.

Scottish bards and harpers did not survive the punitive measures which followed the uprisings of 1715 and 1745. The harp was completely supplanted by the bagpipes and the fiddle. In recent years, we have witnessed a revival of the harp in Scotland with the Society of Harpists Comunn Na Clarsaich. In Wales, the harp has followed its own evolution. From the Irish harp, the Welsh, seeking chromaticism, developed a large harp with three rows of strings. This overly difficult system has been almost abandoned for a long time. Welsh harpists now only use the Irish harp and especially the classical Ehrard harp.

In Brittany — It was mainly the missionaries who came from island Brittany during Breton immigration who brought the harp to Armorica.

We know of numerous representations from the 11th century. In 1079, a charter given in Nantes named a certain Cadiou as official harper of Duke Hoel. In 1189, Richard I the Lionheart called on Breton harpers for his coronation.

After having spread throughout Europe (see the numerous stained glass windows, tapestries or paintings, where we can admire medieval harps derived from the Irish harp). It disappeared when the Bretons lost their independence, already abandoned like the Breton language and culture by the aristocracy fascinated by the French court. But this harp which had never ceased to resound in the small seigniorial courts and festivities throughout the Middle Ages had remained very much alive in our memory, more beautiful, more evocative perhaps of being no more than a symbol of art, poetry, grace, purity, enchantment.

Jord Cochevelou

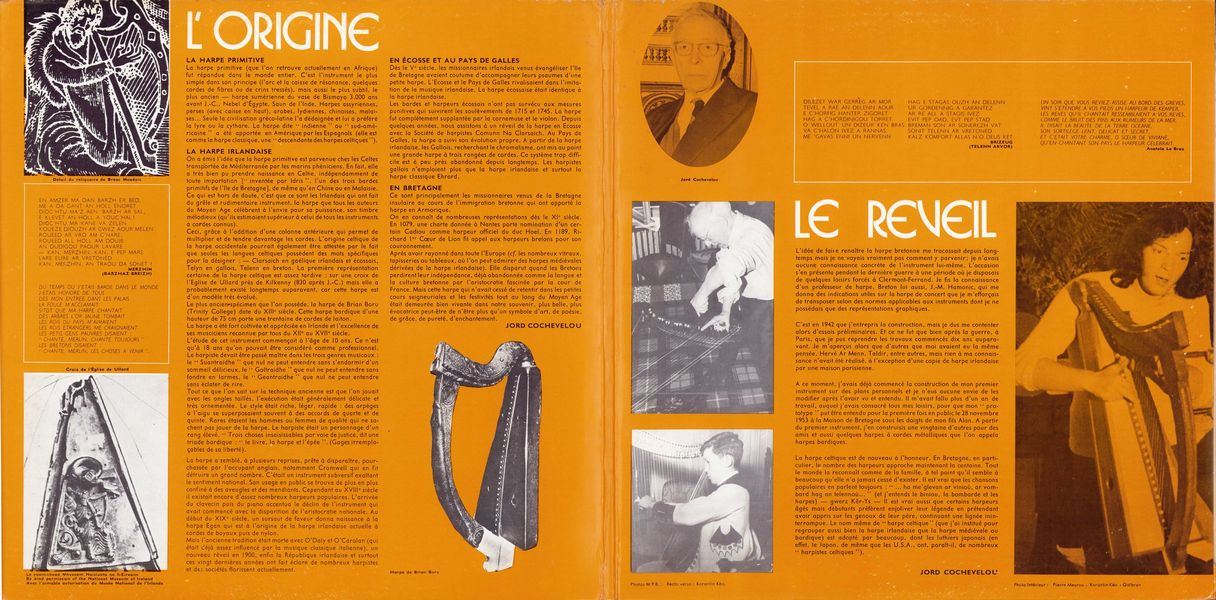

The Revival

The idea of reviving the Breton harp had bothered me for a long time but I really didn't see how to achieve it; I had no concrete knowledge of the instrument itself. The opportunity presented itself during the last war at a time when I had some forced leisure time in Clermont-Ferrand. I met a harp teacher, also Breton, J.-M. Hamonic, who gave me useful information on the concert harp which I was trying to transpose according to standards applicable to instruments which I did not own. than graphical representations.

It was in 1942 that I undertook construction, but then I had to content myself with preliminary tests. And it was only well after the war, in Paris, that I was able to resume the work begun ten years previously. I then realized that others besides me had had the same thought, Hervé Ar Menn, Taldir, among others, but nothing to my knowledge had been made, with the exception of a copy of an Irish harp by a Parisian house.

At that time, I had already started building my first instrument on personal plans and I had no desire to modify them after seeing and hearing it. It took me more than a year of work, to which I had devoted all my leisure time, for my "prototype" to be heard for the first time in public on November 28, 1953 at the Maison de Bretagne under the fingers of my son Alan. From the first instrument, I built around twenty others for friends and also some harps with metal strings which we called bardic harps.

The Celtic harp is once again in the spotlight. In Brittany, in particular, the number of harpers is now approaching a hundred. Everyone recognizes her as family, so much so that it seems to many that she never ceased to exist. It is true that popular songs always talk about it: " … ha me'glevan ar viniou, ar vom-bard hag an telennou … " (and I hear the biniou, the bombarde and the harps) — gwerz Kêr -Ys — It is also true that some older but beginner harpers prefer to embellish their legend by claiming to have learned at their father's knee, continuing an unbroken lineage. The very name "Celtic harp" (which I instituted to include both the Irish harp and the medieval or bardic harp) is adopted by many, including Japanese luthiers (in fact, Japan, as well as the U.S.A., have, it seems, many "Celtic harpists").

Jord Cochevelou

Original French translated via Google Translate.