|

|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

There used to be a street singer cum comedian-style chappie round about Wexford at the turn of the century and his name was Johnny Patterson and he was famous for lots of songs including The Stone Outside Dan Murphy's Door and The Garden Where The Praties Grow.

The first time I heard The Pogues I was put in mind of Johnny — except not so much the real Johnny but Bizarro Johnny, the kind you might meet if Johnny had ever made an appearance in DC Superman comics along with Mr Mxylpltk. Where his face would look like it was made of broke-up bricks and instead of making childrens parties memorable and fun to attend, he would be wrecking them, setting fire to curtains, etc — for no apparent reason whatsoever. Then he would laugh — but not an ordinary laugh but one that was like one you'd expect to hear out of Balor Of the Evil Eye or someone with a rocket shoved up his hole. I never heard such a banging of drums as I heard on that first occasion. It was hard to know whether the accordion player belonged to the band or whether he'd just wandered in by accident. All I could think of was it's like a wedding but who's getting married is the Beast and Bean De Valera. I felt like an old fellow sitting on a gate after the fairies have just lifted his kidneys. There was no doubt about it but it was some sound. I kept thinking to myself if James Stephens and James Joyce had've had themselves a bastard child it'd have done the same yelping as Shane MacGowan was doing — but that would have left out the bit that was Larry Cunningham. Then there was his suit — that was a good one. It was a class of a Kilburn teddyboy outfit and you could wear just the suit or the jacket. Drainpipey-type jobs. I once met a fellow in The Crown in Cricklewood and the size of his sideburns — you never saw the like. You could've played ice hockey with them. He sang Elvis to me. 'Blue Moon Of Kentucky' — that was in there too with the old Pogues. But so were Mick Jagger, Count John McCormack and Maisie McDaniel. I think if you listen carefully you can hear The Searchers — sort of mixed in with Margaret Barry. But I might be imagining that.

I said to my mother: "Do you see what's on the telly?". "Oh now", she replied and emptied more cloves out of her little box. "It's called The Sick Bed Of Cuchulainn", l told her. "The sick bed of what?", she replied, wearily adding: "These veins are killing me."

Then she sat down by the fire to eat the cloves. It was only when I was halfway through a speech about Lord Birkenhead, the treaty and me auld brown parcel that was tied up with string that the hairy cockney combo started playing 'Honky Tonk Women' and I treated myself to a dance with her around the kitchen. Or at least I thought I did. It was only after they'd finished Yeah yeah yeah yeah that I realised she'd been dead for fifteen years and hadn't been sitting along with me at all. Nonetheless, it was a good old session and I have the Pogues to thank for it.

As for me and the rest of my life, well I'm off to outer space on the B&l ferry with my copy of Ireland's Own tucked under my oxter and, with a bit of luck, The Pogues might join me and Johnny Patterson for a lemonade. We'll be the boys with the big white wings that's stamped EIRE, just up the road there from the rebel county hell.

Beir bua aris, a spailipini iontacha, for sibhse na fir is fucking psycho ar fud an wide wide domhain!

Patrick McCabe

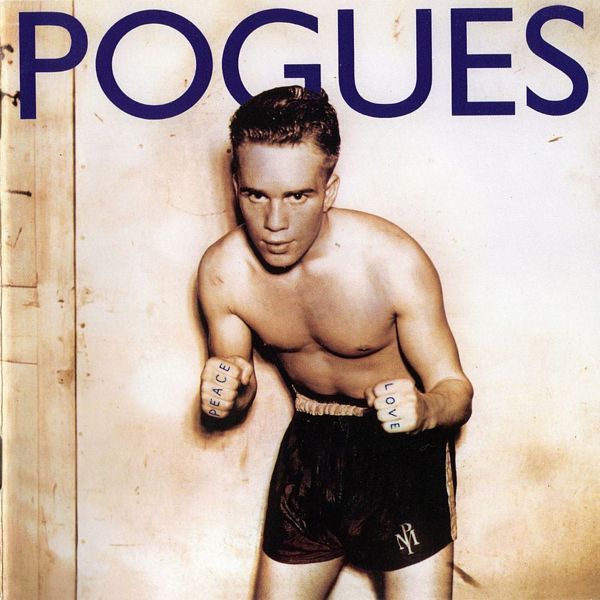

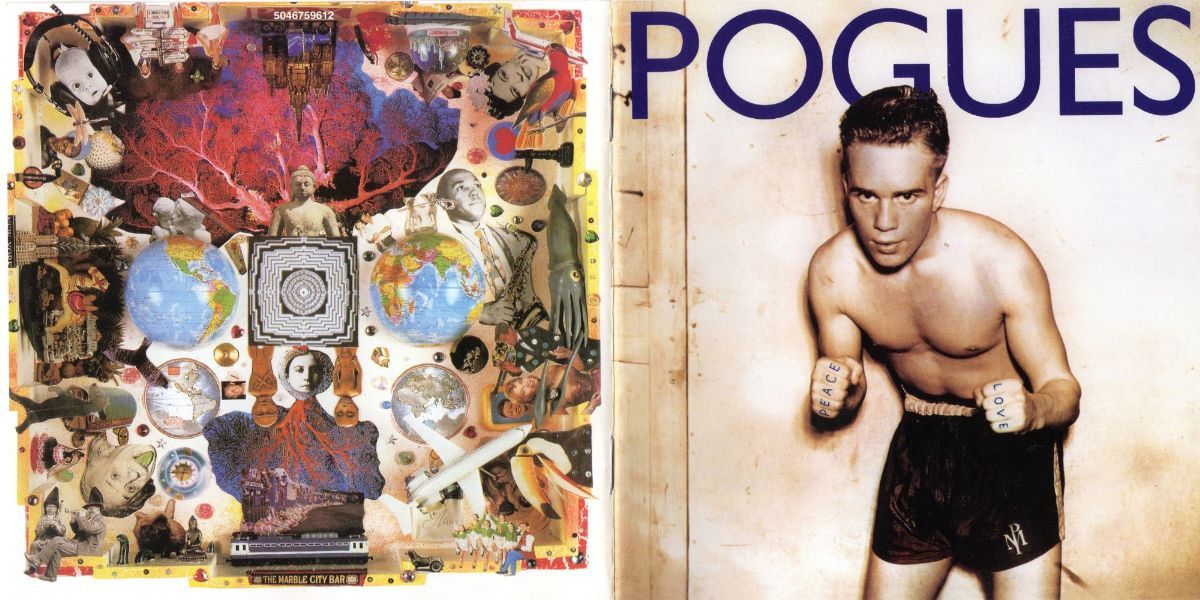

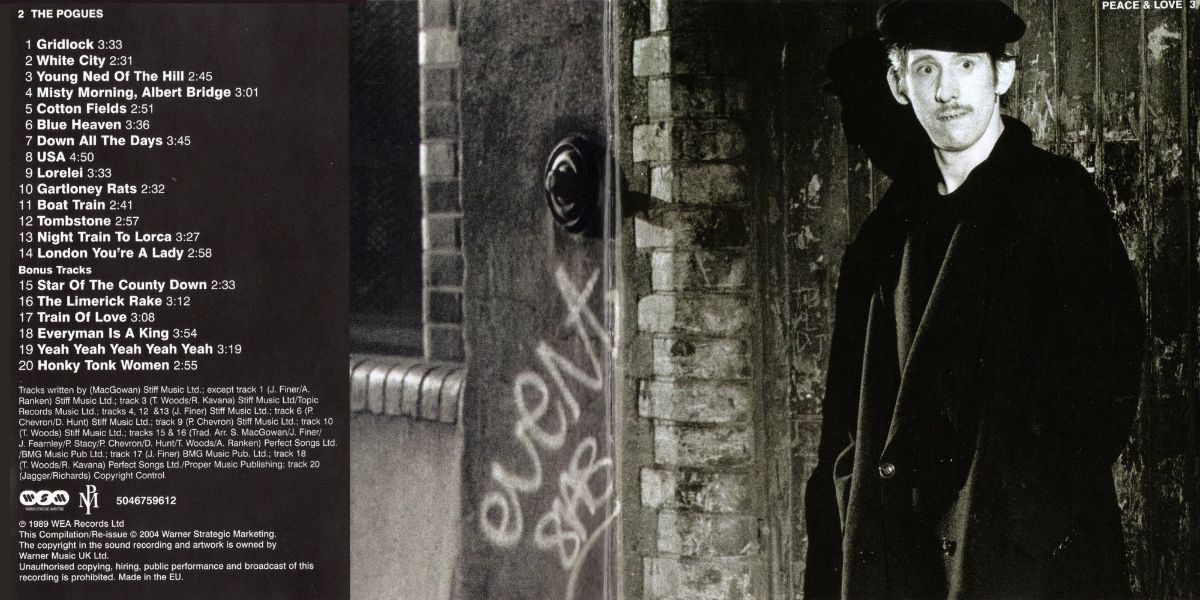

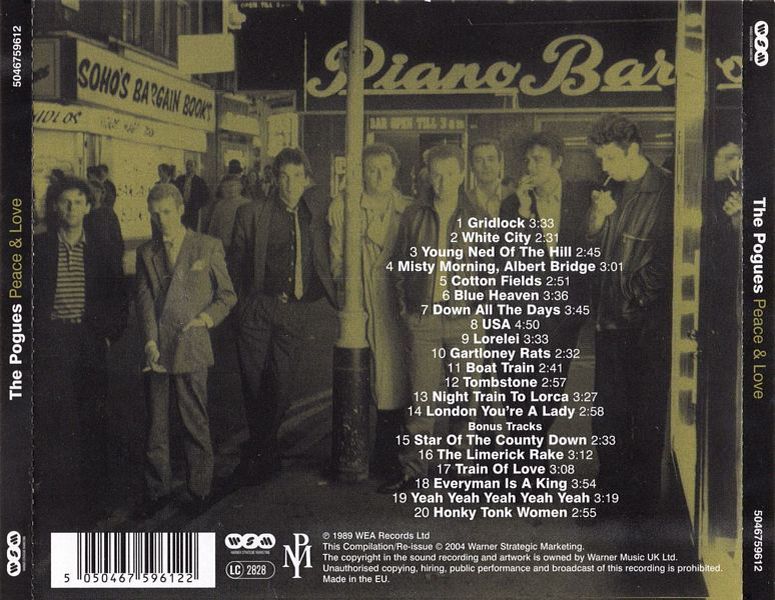

In July 1989, the Pogues released their fourth album, Peace And Love. Like its predecessor, If I Should Fall From Grace With God, Peace And Love was produced by Steve Lillywhite. But where If I Should Fall introduced the world and the Pogues to each other, and finally gave the band the international platform that they deserved, Peace And Love was an indicator of a much more difficult time in the Pogues' career.

For a start, they were now a big band — and not just in the sense of membership and/or jazziness (although Peace And Love's opening track Gridlock signified that, for an Irish pub band, the Pogues could, when they wanted, sound an awful lot like Benny Goodman). 'Fairytale Of New York' had been a massive hit, selling 200,000 copies in the US alone. The Pogues were admired by their peers, as everyone from Bruce Springsteen to Matt Dillon lined up to praise them, appear in the videos or offer them tour supports. In the UK, only the might of the Pet Shop Boys covering an old Elvis Presley tune had prevented the Pogues from having the Christmas number one single. The world was theirs for the taking; the only problem was, they didn't really want it.

The Pogues were going through what Phil Chevron later called "a very volatile period". Acid house and its related substances had become part of Shane MacGowan's life, taking him somewhat further from Irish traditional music than the band's fans might have predicted. In fact, Shane was so taken with the emerging rave scene that he recorded an acid house track himself, called 'Connect With Yourself. The band might have been happier about this had he decided just to release it under a pseudonym, in a pop tradition followed by everyone from Paul McCartney downwards, or even as a single under his own name. Instead, Shane wanted the track to appear on the next Pogues album. This plan became the source of some tension within the band, who sensibly wanted to consolidate their sound in people's minds, not change it completely.

Then there was Shane's other form of participation in the new musical era. He didn't so much switch from alcohol to hallucinogens as combine the two, a recipe for personal enjoyment that didn't necessarily translate to the recording studio. "That changed things," said Chevron with some understatement, "because we constantly had to work around his state of mind. So for the next album, we said let's publish and be damned. We were unhappy so let's tell people we were."

Other factors came into play. Darryl Hunt and Chevron had both witnessed the 1989 Hillsborough disaster, where hundreds of fans were killed at a football match. Other band members were coming to the fore as song-writers. Peace And Love is the first Pogues album where each member makes a significant song-writing contribution. And, in a band as large as the Pogues now were, this would inevitably lead to a deal of musical diversification. There was big band music (Gridlock), there was guitar pop (Blue Heaven), there was traditional folk (Gartloney Rats) and, when one of the album's best tracks, Terry Woods' 'Young Ned Of The Hill' was remixed for a b-side, there was even dub reggae. The Pogues were now capable of playing any kind of music, and very often they did just that. (Of the cornucopia of new tracks on this issue of Peace And Love, particular fun is to be had with Spider's rendition of the Stones' 'Honky Tonk Women', where he acquits himself manfully, despite the intimidating presence on backing vocals of Scottish razor-throat singer/songwriter Frankie Miller. There is also that song's original A-side, the slightly neglected but still classic 'Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah', Shane's raging tribute to Northern Soul.)

Not that there was room for something quite as extreme as acid house.

"None of us were going to walk into Warner Brothers and say 'here is our new album, and by the way one whole side is a jazz acid house contraption called 'Contact Yourself" said Chevron later. "There was room for certain degrees of ideas where you could say 'okay we can have a jazz track like 'Gridlock'. 'Blue Heaven' was a response to being in the southern states of America. Daryl and I had built into it all our fears and paranoias about Hillsborough. Both of us had a really hard time after that. We were seeing things coming out of the fucking walls!"

More positively, the Pogues saw themselves as a band with a role to play. Their effortless use of international ideas and eclectic song-writing fit right into a time when people had stopped pigeon-holing music according to where it came from, and started to see how the dots all joined up.

"At the time there was a whole concept of world music. We felt that we played a fairly strong role in making that happen." said Chevron. "We thought at one stage that we could do pretty much what we wanted." The sessions for Peace And Love were erratic, but hard-working. When Shane was up for it, he could be seen working until the early hours of the morning on songs. The rest of the band worked hard on their contributions, and Peace And Love is as a result of the most musically varied of all Pogues albums. Not that it sounds like a deranged visit to the contents of Peter Gabriel's ideal festival line-up; many of the most memorable songs could have appeared on any Pogues album. Shane's superb 'White City', which deals with the demolition of one of London's most famous dogracing tracks, has a melody and a pace which puts it up with the best of the Pogues singles, while Jem's 'Misty Morning', 'Albert Bridge' — the first Pogues CD single — is a melancholic charmer written in a dingy room in New Zealand.

Seen at the time as something of a weaker sister to If I Should From Grace …, Peace And Love has, over time, revealed its strengths. It opens, rather startlingly, with the jazz instrumental 'Gridlock'. This might have made a few fans take their albums back to the shop, but it works. "I wouldn't say it is the start of a new direction," said Jem Finer, who co-wrote the track with Andrew Ranken, but it is the logical conclusion of a track like 'Metropolis' … I wouldn't take it as an indication of us turning into a hard Bach octet or something like that." Terry Woods certainly had no such plan. Both his songs, 'Young Ned Of The Hill' and 'Gartloney Rats', are rooted in Irish traditional music. "I find diversity occasionally overwhelming," he said at the time. "But in an eight-piece band, you have to bite your tongue sometimes."

Tradition is also served in another of MacGowan's best songs, the lyrical 'Down All The Days'. A tribute to the Irish author Christy Brown, whose life was told in the movie My Left Foot, and whose irascible, creative personality must have struck a chord with Shane, 'Down All The Days' is a classic MacGowan song, quirky, emotive and cutting at once to the personal. As is, in a different way, 'Boat Train', a song which dates back, historically and sonically, to the band's earliest days. Spider screams, Shane roars, and an awful lot of different kinds of drink are listed.

Then there's Jem Finer's 'Tombstone', a tribute to the Aboriginal vision of Australia. Its environmental concerns are the nearest the album gets to Shane's explanation of Peace And Love's title. "The title Peace and Love is about the state the world is in," said Shane. "This fucking world, right, has got ten years to sort itself out. Ten years. London's already completely fucked. I used to love it. Now I'm scared to walk out on the street."

None of this attitude to the capital transferred across to one of the album's cornerstone songs, the epic 'London You're A Lady'. Worth it for a rolling, tumbling melody, and the brilliant line "Your builders, sane but drunk". 'London You're A Lady' is one of Shane MacGowan's best geographical tribute songs, and a great note, or set of notes, to end the original album on.

The rest of the Peace And Love era was not, however, quite as neat. Invited to support Bob Dylan in America, Shane collapsed at Heathrow Airport on his way out to San Francisco. The rest of the band met in the US, only to find that it was Labor Day weekend and all their equipment had been put into storage and locked away. So, playing with borrowed equipment and without their lead singer, the Pogues played their first show. It was a huge success.

"We did this gig with Mickey Mouse equipment, without Shane, and got a standing ovation" said Jem.

Next, the band went out on their own tour. Again, Shane failed to make the first night.

"Other bands in a situation like that would've either said, 'Let's get rid of the guy,' or 'Let's split up,"' said Chevron. "We're not the sort to do that. We don't think of Shane as a problem. We're all part of each others problems, whether we like it or not."

Prophetic words, as it was to turn out.

David Quantick