|

|

Sleeve Notes

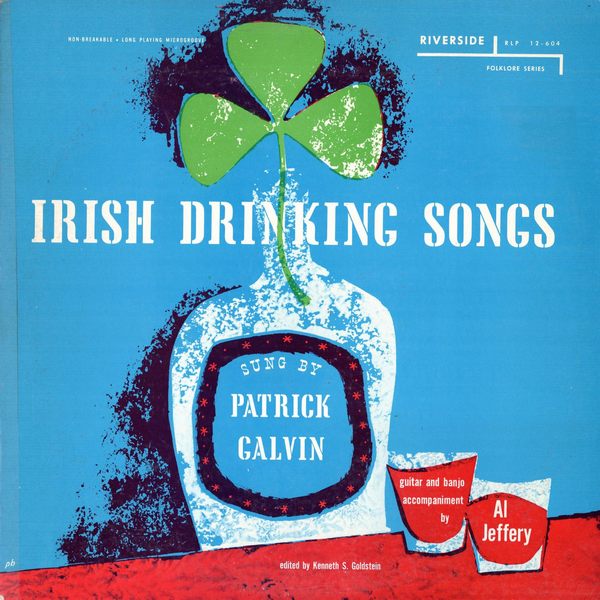

IRISH DRINKING SONGS is a somewhat artificial classification for the songs included in this album, in that it could be taken to mean that only songs of this sort would be sung at "drinking parties." In such a conception there are two errors: first, that the Irish are given to such "drinking parties," and secondly, that there is a certain narrowness in the choice of songs at get-togethers. In fact the characteristic Irish get-together is what we call a hooley, which is a social evening including dancing as well as singing, and food as well as drink, and at which the songs always include a good many of the national (or "rebel") songs and ballads, a toast to Irish rebels being an invariable part of the evening. Thus the songs given here could be considered characteristic only if liberally interspersed with songs of the rebel type. This is not to say that the Irish hooley is a solemn or sanctimonious affair; not only are the songs of the type given here mainly rollicking and rumbustious, but many of the rebel songs are spirited and cheerful, as well.

These songs have been selected so as to give an impression of varying types of songs whose merit is their entertainment value. The audiences normally know the words well and always join in the chorus or even in the whole song.

As will be seen from the notes, some of the songs are no longer widely current in Ireland, but are included for historical and exile interest.

Some of the songs are, of course, clearly Anglo-Irish, in the sense that they are the product of outsiders, or part-outsiders, endeavoring to express an Irish atmosphere, and with great sympathy and affection. It may be doubted whether such characters as Tim Finnegan and Jeremy Lannigan ever existed or could exist in reality any more than did Handy Andy (a good-natured, blundering Irish lad in Samuel Lover's novel by that name), but they represent on the one hand an Irish striving, and on the other an Anglo-Irish sympathy, for the right to enjoy oneself in one's own way. This was inadequate to the greater national strivings of Ireland, and the heyday of Anglo-Irishism is long past, but it has its historical place.

It is hoped that listeners will themselves join in the songs and get the most out of this record by imagining themselves for a while at a hooley in an Irish country kitchen, or at a gathering of Irish exiles settling down to a good old Irish evening. So, • clear the floor, boys, shake yer trotters and mind the dresser! The whiskey is coming up!

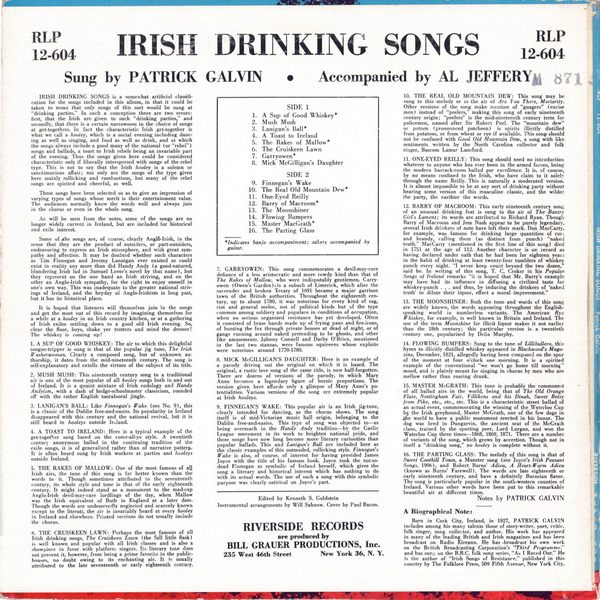

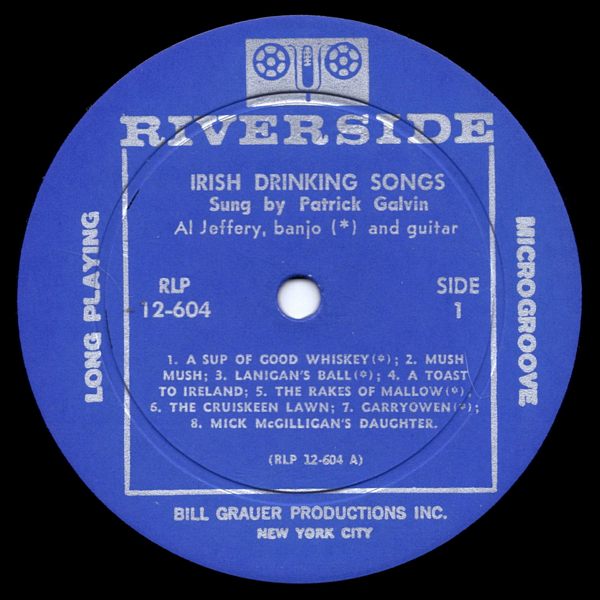

A SUP OF GOOD WHISKEY: The air to which this delightful tongue-tripper is sung is that of the popular jig tune, The Irish Washerwoman, Clearly a composed song, but of unknown authorship, it dates from the mid-nineteenth century. The song is self-explanatory and extolls the virtues of the subject of its title.

MUSH MUSH: This nineteenth century song to a traditional air is one of the most popular of all hooley songs both in and out of Ireland. It is a quaint mixture of Irish codology and Handy Andyiim, with a dash of hedge-schoolmaster classicism, rounded off with the rather English tooralooral jingle.

LANIGAN'S BALL: Like Finnegan's Wake (see No. 9), this is a classic of the Dublin free-and-easies. Its popularity in Ireland disappeared with this century and the national revival, but it is still heard in hooleys outside Ireland.

A TOAST TO IRELAND: Here is a typical example of the get-together song based on the come-all-ye style. A twentieth century anonymous ballad in the continuing tradition of the exile songs, it is of generalized rather than of narrative pattern. It is often heard sung by Irish workers at parties and hooleys outside Ireland.

THE RAKES OF MALLOW: One of the most famous of all Irish airs, the tune of this song is far better known than the words to it. Though sometimes attributed to the seventeenth century, its whole style and tone is that of the early eighteenth century. It might indeed stand as a monument to the mad-cap Anglo-Irish devil-may-care lordlings of the day, when Mallow was the Irish equivalent of Bath in England at a later date. Though the words are undeservedly neglected and scarcely known except to the literati, the air is invariably heard at every hooley in Ireland and elsewhere. Printed versions do not usually include the chorus.

THE CRUISKEEN LAWN: Perhaps the most famous of all Irish drinking songs, The Cruiskeen Lawn (the full little flask) is well known and popular with all Irish classes and is also a showpiece in favor with platform singers. Its literary tone does not prevent it, however, from being a prime favorite in the public-houses, no doubt owing to its enchanting air. It is usually attributed to the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century.

GARRYOWEN: This song commemorates a devil-may-care defiance of a less aristocratic and more rowdy kind than that of The Rakes of Mallow, who were indisputably gentlemen. Garryowen (Owen's Garden) is a suburb of Limerick, which after the surrender and broken Treaty of 1691 became a major garrison town of the British authorities. Throughout the eighteenth century, up to about 1780, it was notorious for every kind of rag, riot and general melee, not of political kinds but of the type common among soldiery and populace in conditions of occupation, when no serious organized resistance has yet developed. Often it consisted of brass bands made up of frying pans and fire-irons, of hunting the fox through private houses at dead of night, or of gangs running around naked pretending to be ghosts, and other like amusements. Johnny Connell and Darby O'Brien, mentioned in the last two stanzas, were famous squireens whose exploits were notorious around 1770-1780.

MICK McGILLIGAN'S DAUGHTER: Here is an example of a parody driving out the original on which it is based. The original, a rustic love song of the same title, is now half-forgotten. There are dozens of versions of the parody, in which Mary Anne becomes a legendary figure of heroic proportions. The version given here affords only a glimpse of Mary Anne's potentialities. Various versions of the song are extremely popular at Irish hooleys.

FINNEGAN'S WAKE: This popular air is an Irish jig-tune, clearly intended for dancing, as the chorus shows. The song itself is of mid-Victorian music hall origin, belonging to the Dublin free-and-easies. This type of song was objected to—as being overmuch in the Handy Andy tradition—by the Gaelic League movement in its work to heighten national pride, and these songs have now long become more literary curiosities than popular ballads. This and Lanigan's Ball are included here as the classic examples of this outmoded, rollicking style. Finnegan's Wake is also, of course, of interest for having provided James Joyce with the title of his famous book. Joyce took the not-so-dead Finnegan as symbolic of Ireland herself, which gives the song a literary and historical interest which has nothing to do with its actual words. The use of such a song with this symbolic purpose was clearly satirical on Joyce's part.

THE REAL OLD MOUNTAIN DEW: This song may be sung to this melody or to the air of Are You There, Moriarity. Other versions of the song make mention of "guagers" (excise men) instead of "peelers," making this song of early nineteenth century origin; "peelers" is the mid-nineteenth century term for policemen, named after Sir Robert Peel. The "mountain dew" or poteen (pronounced potcheen) is spirits illicitly distilled from potatoes, or from wheat or rye if available. This song should not be confused with Good Old Mountain Dew, a song with like, sentiments written by the North Carolina collector and folk singer, Bascom Lamar Lunsford.

ONE-EYED REILLY: This song should need no introduction whatever to anyone who has ever been in the armed forces, being the modern barrack-room ballad par excellence. It is, of course, by no means confined to the Irish, who have claim to it solely through the name Reilly. This is naturally a moderated version. It is almost impossible to be at any sort of drinking party without hearing some version of this masculine classic, and the wilder the party, the earthier the words.

BARRY OF MACROOM: This early nineteenth century song of an unusual drinking feat is sung to the air of The Bantry Girl's Lament; its words are attributed to Richard Ryan. Though Barry of Macroom and Jem Nash appear to be purely legendary, several Irish drinkers of note have left their mark. Dan MacCarty, for example, was famous for drinking large quantities of run and brandy, calling them (as distinct from punch) "naked truth." MacCarty (mentioned in the first line of this song) died in 1751 at the age of 112. Another character is on record as having declared under oath that he had been for eighteen years in the habit of drinking at least twenty-four tumblers of whiskey punch every night. "I never keep count beyond the two dozen," said he. In writing of this song, T. C. Croker in his Popular Songs of Ireland remarks "it is hoped that Mr. Barry's example may have had its influence in diffusing a civilized taste for whiskey-punch … and thus, by inducing the drinkers of 'naked truth to dilute their liquor, effect a moral improvement."

THE MOONSHINER: Both the tune and words of this song are widely known, the words appearing throughout the English-speaking world in numberless variants. The American Rye Whiskey, for example, is well known in Britain and Ireland. The use of the term Moonshine for illicit liquor makes it not earlier than the 18th century; this particular version is a twentieth century one, popularized by Delia Murphy.

FLOWING BUMPERS: Sung to the tune of Lillibullero, this hymn to illicitly distilled whiskey appeared in Blackwood's Magazine, December, 1821, allegedly having been composed on the spur of the moment at four o'clock one morning. It is a spirited example of the conventional "we won't go home till morning" mood, and is plainly meant for singing in chorus by men who are mellow rather than roaring drunk.

MASTER McGRATH: This tune is probably the commonest of all ballad airs in the world, being that of The Old Orange Flute, Nottingham Fair, Yillikens and his Dinah, Sweet Betsy from Pike, etc., etc., etc. This is a characteristic street ballad of an actual event, commemorating the winning of the Waterloo Cup by the Irish greyhound, Master McGrath, one of the few dogs in the world to have a public monument erected in his honor. The dog was bred in Dungarvin, the ancient seat of the McGrath clans, trained by the sporting peer, Lord Lurgan, and won the Waterloo Cup three times—1868, 1869, 1871. There are a number of variants of the song, which grows by accretion. Though not in itself a "drinking song," no hooley is complete without it.

THE PARTING GLASS: The melody of this song is that of Sweet Coothill Town, a Munster song (see Joyce's Irish Peasant Songs, 1906), and Robert Burns' Adieu, A Heart-Warm Adieu (known as Burns' Farewell). The words are late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, and have a definitely Burnsian flavor. The song is particularly popular in the south-western counties of Ireland. Various other words have been put to this remarkably beautiful air at different times.

Notes by PATRICK GALVIN

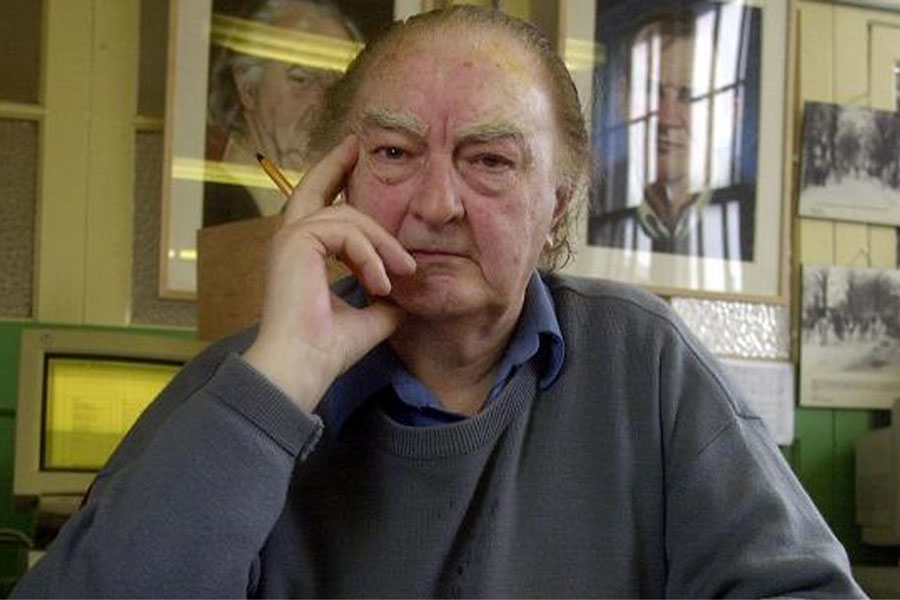

A Biographical Note:

Born in Cork City, Ireland, in 1927, PATRICK GALVIN includes among his many talents those of story-writer, poet, critic, folk singer, song collector, and author. His work has appeared in many of the leading British and Irish magazines and has been broadcast on Radio Eireann. He has broadcast his own work on the British Broadcasting Corporation's "Third Programme." and has sung on the B.B.C. folk song series, "As I Roved Out." He is the author of "Irish Songs of Resistance," published in this country by The Folklore Press, 509 Fifth Avenue, New York City.