|

|

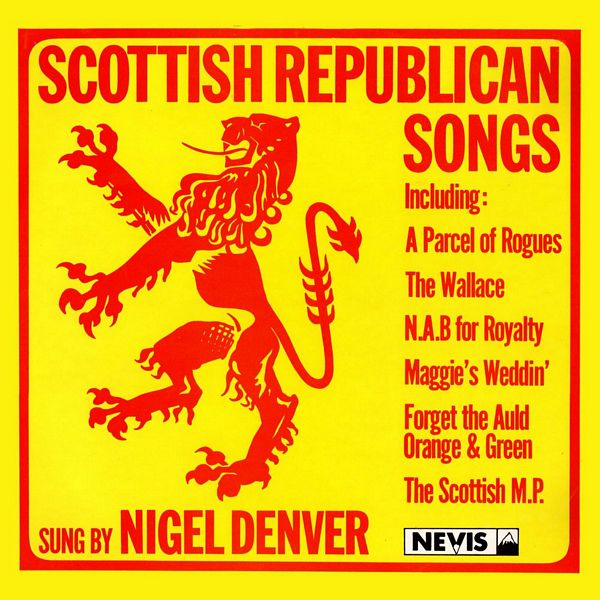

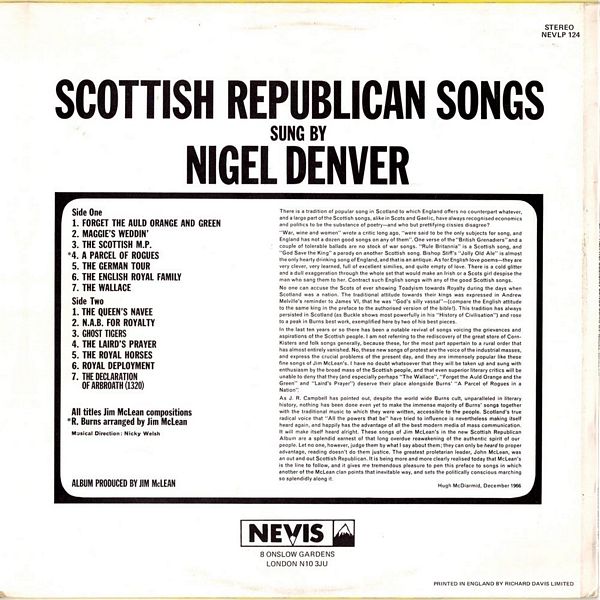

Sleeve Notes

There is a tradition of popular song in Scotland to which England offers no counterpart whatever, and a large part of the Scottish songs, alike in Scots and Gaelic, have always recognised economics and politics to be the substance of poetry — and who but prettifying cissies disagree?

"War, wine and women" wrote a critic long ago, "were said to be the only subjects for song, and England has not a dozen good songs on any of them".One verse of the"British Grenadiers"and a couple of tolerable ballads are no stock of war songs. “Rule Britannia" is a Scottish song, and "God Save the King" a parody on another Scottish song. Bishop Stiff's "Jolly Old Ale" is almost the only hearty drinking song of England, and that is an antique. As for English love poems — they are very clever, very learned, full of excellent similies, and quite empty of love. There is a cold glitter and a dull exaggeration through the whole set that would make an Irish or a Scots girl despise the man who sang them to her. Contract such English songs with any of the good Scottish songs.

No one can accuse the Scots of ever showing Toadyism towards Royalty during the days when Scotland was a nation. The traditional attitude towards their kings was expressed in Andrew Melville's reminder to James VI, that he was "God's silly vassal" — (compare the English attitude to the same king in the preface to the authorised version of the bible!). This tradition has always persisted in Scotland (as Buckle shows most powerfully in his "History of Civilisation") and rose to a peak in Burns best work, exemplified here by two of his best pieces.

In the last ten years or so there has been a notable revival of songs voicing the grievances and aspirations of the Scottish people. I am not referring to the rediscovery of the great store of Corn-Kisters and folk songs generally, because these, for the most part appertain to a rural order that has almost entirely vanished. No, these new songs of protest are the voice of the industrial masses, and express the crucial problems of the present day, and they are immensely popular like these fine songs of Jim McLean's. I have no doubt whatsoever that they will be taken u[5 and sung with enthusiasm by the broad mass of the Scottish people, and that even superior literary critics will be unable to deny that they (and especially perhaps "The Wallace", "Forget the Auld Orange and the Green" and "Laird's Prayer") deserve their place alongside Burns' "A Parcel of Rogues in a Nation".

As J. R. Campbell has pointed out, despite the world wide Burns cult, unparalleled in literary history, nothing has been done even yet to make the immense majority of Burns' songs together with the traditional music to which they were written, accessible to the people. Scotland's true radical voice that "All the powers that be" have tried to influence is nevertheless making itself heard again, and happily has the advantage of all the best modern media of mass communication. It will make itself heard alright. These songs of Jim McLean's in the new Scottish Republican Album are a splendid earnest of that long overdue reawakening of the authentic spirit of our people. Let no one, however, judge them by what I say about them; they can only be heard to proper advantage, reading doesn't do them justice. The greatest proletarian leader, John McLean, was an out and out Scottish Republican. It is being more and more clearly realised today that McLean's is the line to follow, and it gives me tremendous pleasure to pen this preface to songs in which another of the McLean clan points that inevitable way, and sets the politically conscious marching so splendidly along it.

Hugh McDiarmid, December 1966