|

|

Sleeve Notes

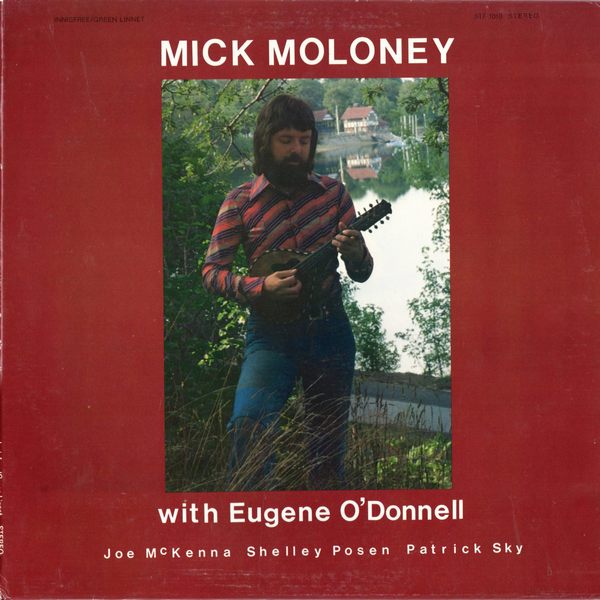

Mick Moloney, a man of many talents, was born in County Limerick, Ireland. There was little traditional Irish music played in his area, but he grew up in a musical environment, as his parents and brothers and sisters played the piano and sang at family gatherings.

Mick got his first real taste of "folk" music from the skiffle music he heard on the radio in the late 1950's. Skiffle drew heavily from the music of Americans such as Leadbelly, Big Bill Broonzy, and Woody Guthrie for its style and repertoire, and from American jug bands for instrumentation — prominently guitar, washboards, and bass. The most influential skiffle performer was the Englishman Lonnie Donegan, who achieved widespread notoriety for his recording of Leadbelly's Rock Island Line, the flip side of which was Does Your Chewing Gum Lose Its Flavor on the Bedpost Overnight?.

Unlike the other pop music dominating the airwaves at the time, skiffle was "new and refreshing" to Mick's ears. It was only a short step from skiffle to the singing of the Clancy Brothers, who soon grew popular in Ireland. And it was inevitable that he should discover the wealth of traditional music being played around him in Ireland.

By the time he entered University College in Dublin. Mick was studying Economics in the classroom but spending his weekends and holidays in County Clare, scarcely 45 minutes from his home in Limerick. There, a whole new world opened before his eyes. Then, as now, Clare abounded in traditional music and musicians of the highest calibre, and Mick was soon meeting and playing with the best of them.

Mick was putting himself through school by singing in a "ballad group" — The Emmet Folk Group — with two friends, Brian Bolger and Dónal Lunny (now a member of The Bothy Band and a well known record producer). The group disbanded before Mick began work toward a Master's in Political Economy, but his involvement in traditional music continued to grow. He and his roommate Paul Brady were playing fairly regularly with many of the great musicians in Dublin traditional music circles.

Their lives soon altered dramatically. Mick was asked to join The Johnstons, a singing group composed of Lucy, Adrienne, and Michael Johnston from County Meath. When Michael left the group, Paul Brady took his place. This musical association spanned five years and resulted in concert tours, radio and TV broadcasts, festival appearances, and seven LPs.

The Johnstons became one of the top folk groups in the British Isles and Ireland, with a repertoire consisting of traditional songs and contemporary material sung in clear, four-part harmony accompanied by Paul on guitar and Mick on mandolin or tenor banjo. The two instrumentalists worked some of the tunes they were learning in their spare time into on-stage sets and LP tracks.

Being part of an actively performing group was exciting and stimulating, but after several years it began to wear thin. After the group's first trip to America in 1971, Mick left The Johnstons to strike out on his own.

He went to Norway and, for almost a year, worked with music in youth clubs, schools and colleges in the Norwegian Education System. Moving to London, Mick became a social worker by day and at night appeared as a solo performer in folk clubs throughout the London area. He released an album on Transatlantic, now, unfortunately, out-of-print.

During his trip to America with The Johnstons, Mick had become friendly with Dr. Kenneth Goldstein, then head of the Folklore and Folklife Department at the University of Pennsylvania. At Kenny's urging, Mick applied to Penn. He was accepted, moved to Philadelphia in 1973, and has lived there ever since.

In the United States Mick has pursued the sometimes separate but usually intertwined careers of folklorist and performer. He is widely respected both as a scholar and as a musician, and has produced a number of fine LPs for domestic record companies and for Topic Records in London. A recent grant from the National Endowment for the Arts enabled Mick to record many outstanding Irish musicians in the eastern United States.

Mick is presently serving as the director of a series of ethnic festivals being presented under the aegis of International House in Philadelphia. He is writing his PhD. dissertation, a study of traditional Irish music in contemporary America, and is also preparing a book on the same subject, to be published by the University of Pennsylvania Press. And, of course. Mick is still performing at concerts and festivals and playing music whenever a chance arises.

Mick's first instrument (besides the piano, which he played ages 8 to 10 and hated) was the guitar, a natural outgrowth of his interest in skiffle music. From the first Mick learned to play melodies — not just chords — on the guitar, and only later found that the picking style he had developed was eminently suited to the playing of traditional Irish music. However, playing in sessions with other musicians he quickly realized the limitations of the guitar for Irish music and decided to learn tenor banjo and mandolin as well. An accomplished guitarist, Mick uses it only to accompany his own singing and Eugene O'Donnell's fiddling.

Mick has always been attracted to the banjo, to which he was first exposed in childhood. He vividly remembers listening to three travelling musicians, the Dunnes, who appeared at fairs and markets in the west of Ireland, play in the streets of a nearby town on Saturdays. The trio used two fiddles and a tenor banjo.

In those days, Mick was spending a great deal of time in Clare meeting musicians and absorbing what he could from them. He was fortunate indeed to meet Willie Clancy, the legendary piper, in Milltown Malbay. Clancy often played with Jimmy Ward, a banjo player, now a member of the Kilfenora Ceili Band. Liking the combination of pipes and banjo. Clancy encouraged Mick in his interests.

Mick learned "an awful lot" of music from James Keane, an accordion player who now lives in New York. Another influence was Paddy O Donoghue, a flute player from Ennis who plays with the Tulla Ceili Band. There were many others. Clare was fertile ground for traditional music.

There were, however, few banjo or mandolin players around to learn from or emulate. Consequently, Mick has fundamentally taught himself as far as technique on each instrument is concerned. But he has also adapted the techniques of other instrumentalists to the banjo and mandolin. Indeed, those who believe that Irish music cannot be played on the banjo should pay close attention to Mick's playing. One does not hear the staccato picking so common among mediocre banjo players. Rather. Mick's playing is as richly varied and ornamented as that of any virtuoso performer on fiddle or flute.

In fact, both these instruments have been influential in developing Mick's banjo style. His years of playing with and listening to flute players in Clare and throughout Ireland are apparent in the way he phrases tunes, punctuating the melody line with brief pauses and split-second stops. I myself believe that much of the lift in Mick's playing is due to this aspect of his style. To the fiddle he owes the left-handed triplets he uses to supplement and complement those produced with his pick. He has also learned to "cran" on the banjo and mandolin; an example occurs in the set of jigs on Side B, in the fourth part of The King of the Pipers.

The banjo's popularity is growing among Irish musicians, and there are many fine players besides Mick himself. One of the best, a stylesetting musician whose technique Mick admires, is Barney McKenna of The Dubliners. Another is Des Mulcair, whom Mick first met in Clare after he had been playing banjo for several years. Mick also admires the playing of Mick O'Connor and Liam O'Farrell of London, Kieran Hanrahan of Clare, Charlie Piggott who plays with De Danann, Mike Flanagan of Albany, New York (one of the Flanagan Brothers, who recorded many 78s for Columbia), and his protege, Mike Leonard. Among the young players he thinks show great promise are Gail Mulvihill and Eileen Ivers, both of New York.

Mick learns most of his material from other people, either in sessions or from tapes of sessions. Only occasionally does he pick up tunes from records. Mick claims he will often hear tunes a few times in sessions and find that he knows them, although never conscious of having learned them. Anyone who knows Mick and had heard him play with countless musicians will attest to his astounding and seemingly limitless repertoire of tunes.

Many of the tunes Mick plays on this record are ones he learned from Irish musicians here in the United States.

Eugene O'Donnell, whose fine and sensitive fiddling adds so much to this recording, and Mick Moloney first met at the 1973 Philadelphia Folk Festival. They were later booked at a local folk club by a mutual friend. Mick and Eugene began appearing together more and more frequently and are now mainstays in Irish music circles in Philadelphia and, indeed, throughout the Northeast.

Eugene was born in Derry, Northern Ireland, and was an accomplished Irish dancer before he played the fiddle. He began to dance competitively while still a youngster. Later, he was six times All-Ireland Step-Dancing Champion and also the first Irish dancer to appear on TV in London. He is a licensed adjudicator for Irish dancing.

His ability as a dancer has made him a sensitive accompanist for dancers — a demanding, thankless task — and his strict tempo, especially while playing set pieces, is but one mark of his dancing heritage.

However, it is for his expressive playing of airs that Eugene is particularly renowned. Few can match his superb control of tone or his mastery of phrasing. The air he plays on Side A, Killin's Fairy Hill, is just a brief, tantalizing glimpse of his ability.

Since moving to the United States 20 years ago. Eugene has been reasonably active as a musician and a dancer. For a while in the mid-60's he played in a prize-winning ceili band in Philadelphia. More recently, before teaming up with Mick, he appeared on his own at concerts and festivals in the Philadelphia area. Eugene has been surprisingly underrecorded considering his ability on the violin and his unusual and extensive repertoire. A series of records for Irish dancers made at one time with piano player Gerry Wallace are. of course, devilishly hard to obtain. Eugene is working on a record of set dances that will be released in the near future by Innisfree on the Green Linnet label.

Michael Stoner

Joe McKenna has been All-Ireland Champion Uilleann Piper on two occasions. He was born in Dublin and learned the pipes under the tutelage of the late Leo Rowsome. He was touring in America during the summer of 1977 with his wife, Antoinette, who sings and plays the harp, and was thus able to play on this recording. Joe and Antoinette have also recorded an LP of their own to be released on the Shanachie label.

Shelley Posen comes from Toronto and is an excellent singer, guitarist and five string banjo and concertina player. He studied for his Master's degree in Folklore at Memorial University in Newfoundland. Since 1974 he has been taking courses toward a Ph.D. at the Folklore and Folklife Department of the University of Pennsylvania. His musical tastes and expertise span a wide range, including British. Irish and Canadian folksongs. American country songs, and Sacred Harp a capella singing.

Patrick Sky — raconteur, singer, composer and guitarist has become in recent years a welcome convert to Irish music. Meeting Liam Og O'Floinn in 1971 turned him on to the uilleann pipes. Playing (and, later, making) this instrument has become Pat's abiding passion. He is also a gifted producer and is responsible for the release by Innisfree of FORTY YEARS OF IRISH PIPING, a double album tracing the development of Seamus Ennis' uilleann piping from the 1930's to the mid-1970's. Pat is currently a member of The Potstill Band, an exciting group who perform inventive arrangements of Irish instrumental music.

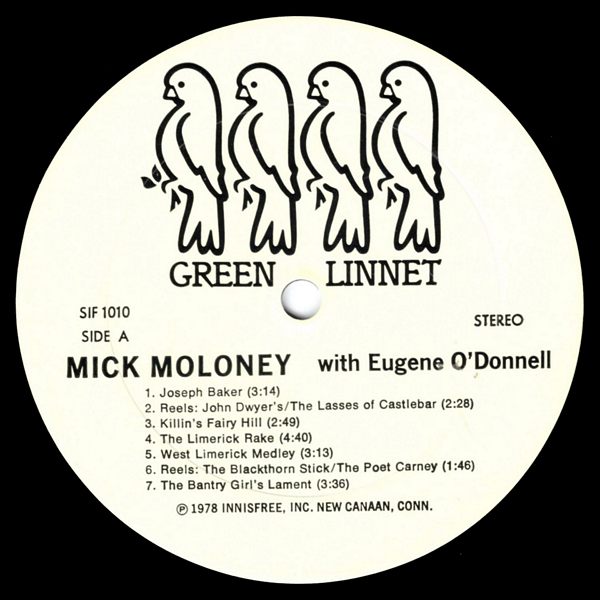

Joseph Baker — The Joseph Baker in question was reputedly a great runner in the English county of Chester. Not much is known about him now, but Pete Coe, also from Chester, rescued these verses from a broadside he found. He adapted the words somewhat and set them to the tune of The Budgeon is a Delicate Trade, which he found in Chappel's Popular Music of the Olden Time. And so Joseph Baker lives again. I learned the song from Seán Cannon, who comes from Galway and sings like a lark, mostly in England these days.

Mick — singing, guitar, bouzouki; Shelley — concertina, singing; Joe — uilleann pipes; Eugene — fiddle.

Reels: John Dwyer's & The Lasses of Castlebar — I've known the first reel for a few years. I don't remember where I learned it. but it might have been when I was living in London. Larry McCullough tells me he heard it played a lot when he was there. It's a composition of John Dwyer, brother of the accordion player Finbar Dwyer. I've half-known The Lasses of Castlebar tor some time, but was impelled to start playing it after hearing a particularly memorable rendition of it by Andy McGann at the Philadelphia Ceili Group's First Traditional Music, Song and Dance Festival in 1975.

Mick — tenor banjo, guitar.

Killin's Fairy Hill — Eugene, though a fine player of dance music, is best known for his sensitive playing of slow airs. He learned Killin's Fairy Hill from a fiddler in Buncrana, County Donegal, some years ago. A love poem of the same name was written in the early 18th century by Peadar O Doirnin (1684-1768), a South Ulster poet. Killin Hill, to which the poet wants to bring his true love, is about two miles northwest of the town of Dundalk. County Louth.

Eugene — fiddle; Mick — guitar

The Limerick Rake — I've known this song for a good many years. I used to sing it quite a bit. but then forgot all about it for a few years. I was looking through Colm O'Lochlainn's first volume of Irish Street Ballads when I came across it again. I like it because of its broad verbose humor and its honest opposition to conservative values. I find especially delightful such lines as the one that refers to "Bacchus sporting with Venus" and the one that rationalizes polygamy on the grounds that "the son of King David had ten hundred wives, and his wisdom is highly recorded". I also like the song because of its encyclopaedic references to towns and villages all over my native County Limerick.

Mick — singing, guitar, bouzouki; Joe — tin whistle.

West Limerick Medley: The Clar Hornpipe/The Pride of Moyvane & The Humours of Newcastle West — I learned these three tunes from Martin Mulvihill, a West Limerickman now living in the Bronx. Martin, who has an LP forthcoming on Innisfree/Green Linnet, is a great old-style fiddler. He learned many of his tunes from the musicians who played for cross roads set dancing in the townlands around his native Ballygaughlin when he was a youth. The first tune is a fast hornpipe, which used to be played regularly to finish the West Limerick sets. The second, The Pride of Moyvane. is one of Martin's own compositions, named after a village just over the county border in Kerry. The third, named after another West Limerick town, is a reel which used to be popular among fiddlers in Martin's own village.

Mick — mandolin, bouzouki.

Reels: The Blackthorn Stick & The Poet Carney — Neither Eugene nor I can remember where or when we learned The Blackthorn Stick happily send you a full catalog of Green Linnet Records. (Breandan Breathnach: Ceol Rince na hEireann II. #214). I've heard it played a lot in New York. The Poet Carney is a composition of Eugene's. He named it after a friend of his in Derry City.

Mick — tenor banjo, guitar; Eugene — fiddle.

The Bantry Girl's Lament — I first heard this sung by Tim Lyons, a great traditional singer from County Cork who now lives in County Clare. We were in the middle of a big session in Lisdoonvarna at the time. I remembered having seen the song in Colm O'Lochlainn's first collection of Irish Street Ballads, so I learned it from the book afterwards. O'Lochlainn reports a version of the tune collected by Patrick Weston Joyce in the mid-19th century. Johnny must have been quite a character to have aroused such grief at his departure to fight the "dirty King of Spain".

Mick — singing, bouzouki; Pat — tin whistle; Joe — tin whistle; Shelley — guitar; Eugene — fiddle.

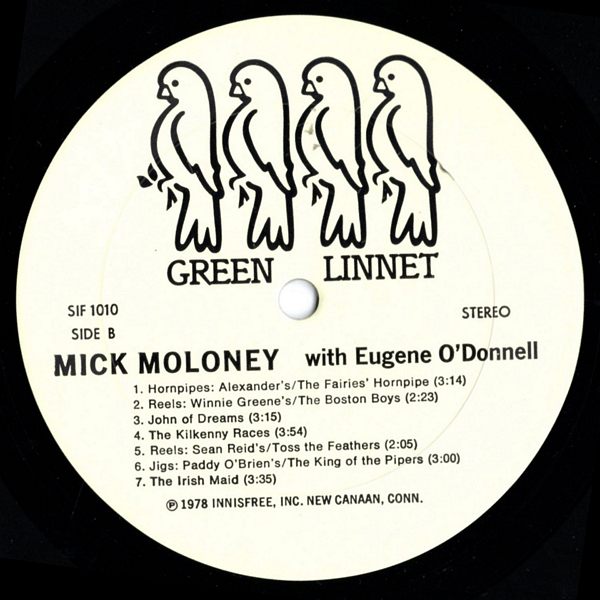

Hornpipes: Alexander's & The Fairies' Hornpipe — During breaks in recording, we sat around playing tunes with one another. We particularly liked playing these two hornpipes together, so they ended up on the record. I can't remember where or when I learned Alexander's (O'Neill's Music of Ireland, #1683). The Fairies' Hornpipe (O'Neill, #1718) I remember hearing played a lot back home by Seamus Ennis, the great uilleann piper.

Mick — tenor banjo, mandolin, bouzouki; Pat — tin whistle; Joe — uilleann pipes; Eugene — fiddle.

Reels: Winnie Greene's & The Boston Boys — I learned both tunes from Paddy Cronin, the great Kerry fiddler now living in Boston. Paddy learned them from Cole's 1001 Fiddle Tunes. A close variant of Winnie Greene's is known as The Graf Spey, which turned up on several 78 rpm recordings in the 1920's and 1930's, sometimes known as The Grand Spree. (I am indebted for this information to Miles Krassen, who, incidentally, also remembers hearing John Summers, an old time American fiddler playing a Southern version of the tune in Indiana).

Mick — tenor banjo, guitar.

John of Dreams — This is another I learned from Seán Cannon. The words were written by Bill Caddick of Wolverhampton. The tune he took from Peter Tchaikovsky's Symphony #6 in Bb minor. Opus 74, The Pathetique. However, Seán Cannon was informed by Toni Savage of Leicester, who studied opera and bel canto in Italy, that the tune was borrowed by the Russian composer from a southern Italian lullabye entitled Piva Piva. So, in a remarkable way, the tune has come full circle.

Mick — singing, bouzouki, guitar; Shelley — singing, concertina; Joe — uilleann pipes; Eugene — fiddle.

The Kilkenny Races — This is a well known set dance piece — well known by musicians who play regularly for set dancing. Outside of the context of dancing competitions, it is rarely played. Of the many set dance pieces Eugene plays, this is my favorite. I particularly like his punctuation and phrasing, especially in the third part of the tune.

Eugene — fiddle; Mick — guitar.

Reels: Seán Reid's & Toss the Feathers — The first is a good piping reel which used to be played a lot by Willie Clancy, the great Milltown Malbay piper. The second (O'Neill, #1224) is found in many different variants in most parts of Ireland. I've always liked the combination of pipes and banjo. Joe and I had quite a few sessions during his visit here, and these are two tunes we found went well together.

Mick — tenor banjo; Joe — uilleann pipes.

Jigs: Paddy O'Brien's & The King of the Pipers — We learned the first jig from Jack and Father Charlie Coen, two County Galway musicians now living in New York. They originally learned it from Paddy O'Brien, the accordion player, who lived in America for some years before returning to Ireland. I first heard The King of the Pipers played by Tommy Caulfield of Philadelphia. He, in turn, got it from Neil Docherty, a great Donegal fiddler, who was one of Philadelphia's foremost musicians until his death in the early 1960's. The tune is probably of Donegal origin.

Mick — mandolin; Eugene — fiddle.

The Irish Maid — This song of Irish lovers parting has been reported once in the New World, as Erin's Flowery Vale (W.M. Doerflinger Shantymen and Shantyboys, New York, 1951). Shelley Posen plays a nice chopping guitar style which blends nicely with Eugene's ever-tasteful fiddling. I learned the song when I was living in England.

Mick — singing; Shelley — guitar; Eugene — fiddle.

Mick Moloney