|

|

Sleeve Notes

These days, when ethnic humour has become acceptable (if not respectable) in the mouths of latter-day folk heroes like Billy Connolly, Max Boyce and Richard Pryor, it is timely that this album should remind us of one of the founding fathers of this revival of the genre in these contemporary times, the late Matt McGinn, who died so tragically in the first week of the year of 1977. When Matt came on the scene as a protege of Ewan MacColl, who devoted an entire side of his important Folkways album, "Revival In Britain", to the talents of this latter-day Zozzimus, Scottish humour was in pretty sad straits. The heirs of Harry Lauder, bekilted denizens of the White Heather kaleyaird like Andy Stewart, had turned it into a polite, acceptable genre watered down for the TV airwaves, with about as much Sauchiehall Street kick to it as a dram of Japanese Scotch.

And as for the radical tradition that runs parallel to it, as broad and blood-red as a scarlet banner through the folk cultures of the world, inspiring a Swedish-American union organiser called Joseph Hillstrom (Joe Hill) in USA and an equally important factor in the work of that Cruchallan fencible, Robert Bums himself, it appeared almost to have died, nowhere to be seen. It survived, however, in the sharp tongues of the folk, in the bawdy tales of Jeannie Robertson and Davey Stewart, so it was hardly surprising that the revival in Scottish comedy should rise upon the shoulders of the folk revival that challenged and shocked the worthy burghers of Edinburgh, with a People's Festival as one of the very first counter festivals, red flag in one hand and a wee ha'f in the other.

A group of Scots, a poet called Thurso Berwick, a folklorist called Hamish Henderson (whose "D-Day Dodgers" had entered into army folklore during the Italian campaign, where he served eventually with the descendents of Gramsci in the partisans), a schoolteacher eventually to become an English cabinet minister, Norman Buchan, and hosts of numerous and anonymous balladeers, came together to revive the ancient Gaelic art of "aoir", or satire, with modern shibboleths like American Polaris submarines in the Holyloch, the stealing of the Stane of Scone from Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1950, the doings of English royalty (always good for a laugh, that, no less then than this Majestical year of Jubilee) and the cause of Scottish nationalism as the subjects.

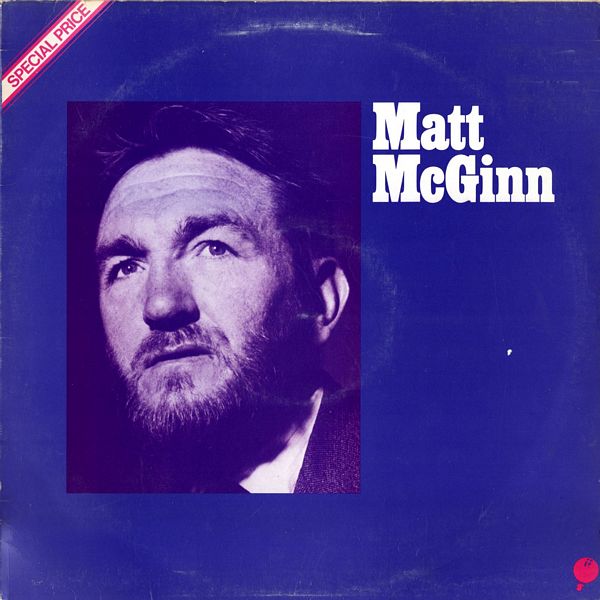

From this clanjamfree emerged Matt McGinn, red-bearded, sparkling-eyed and bushy-tailed, who borrowed anything he needed from anyone's culture: an IRA march for an Aldermaston peace song, a "big" ballad tune ("Johnny O'Breadislee") for a song about the American space programme, a vicious chorus to the Irish anti-war ballad, "The Kerry Recruit", for a song about the craft and art of muckspreading, a calypso tune for a song about hire purchase ("I.O.U.") or hard times ("Moanin' Never Did Nae Good").

And around him gathered the children of the revival, young Tam Harvey and his marra, Billy Connolly, later to achieve the sort of fame with their first classic album as the Humblebums. That was before Gerry Rafferty joined. I wonder what ever happened to young Billy?

There was also a much slimmer Hamish Imlach, I recall, and an incredible young man by name of Robin Williamson, much given to a mixed diet of Scottish reels and banjo ragtime tunes.

But at the heart of it all was Matt — irreverent, concerned, bitter and joyful in turns — friend of Pete Seeger and as familiar to the audience at Newport as he was down the Gallowgate. The songs and stories poured out of him in an ever-ending stream, good, bad but never indifferent. "Matt McGinn's power of invention has run dry", went the crack in the folk pubs. "He hasn't written a song for two weeks". A gross libel, for I doubt if a day went by without him scribbling down something or other.

They were the good times, when he could earn a couple of hundred dollars any night in the States to Bob Dylan's sixty. Young Jewish boys singing the blues they could hear on almost any Greenwich Village street corner, but Matt McGinn, they recognised, was a true original, unduplicable. Refuse all imitations.

Fine songwriter that he was, Matt's talent wasn't to be confined inside any idiom.

He quarreled with his folk mentors, and wrote a wicked satire on MacColl called "Achin' Drum" (based, of course, on the old Scots children's song, "Aiken Drum" — work it out, if you can). He trod the boards in ‘Macbeth' at the Edinburgh Festival, and then he returned a year or two later with a one-man show.

Then, as times changed, one saw less and less of him. The Folk Festivals started booking the younger kids, who didn't always have Matt's sparkle, nor his balls. He was writing a book, one heard. Then he had finished that one, and was at work on a sequel before the first one was even out. And, more sadly, he was taking the cure, for he was no longer a well man.

Then one night past midnight, Norman Buchan's wife Janey rang me from Rutherglen to tell me that he had died tragically, ridiculously, by falling on to an electric fire and burning himself to death. This great socialiser, raconteur and man among men was living alone, without a friend to pull him from the fire.

The night seemed colder without knowing he was alive somewhere, even though I hadn't seen him for something like a decade. There was a funeral, and there were flowers from Sandy Bell's, the "Forest Hill Bar" where so much of the Edinburgh folk scene was centred, and they laid him away.

But, as another songwriter once said of Joe Hill, he had something that can't be interred so easily. The next time you see a broad Scots or Welsh comic swapping wisecracks with Michael Parkinson (another ethnic humorist) on TV, remember who started it all, and smile for Matt.

Karl Dallas