|

|

Sleeve Notes

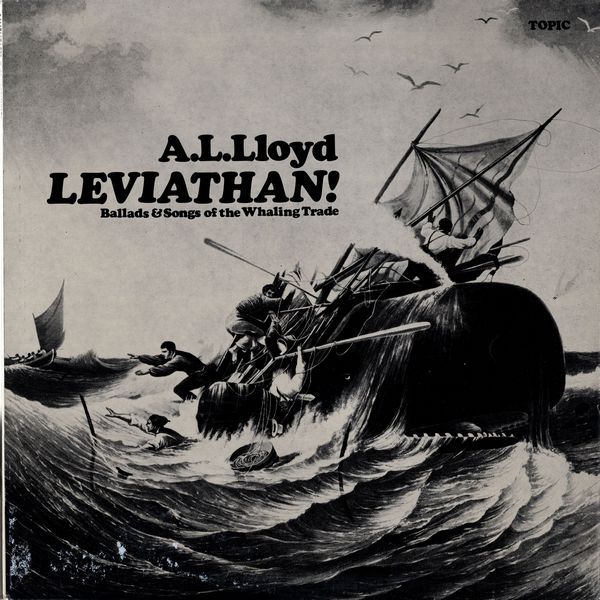

This record is something of a nostalgic exercise. At Bromborough, Liverpool, half a lifetime ago, I joined the whaling ship Southern Empress. Antarctic bound on a seven months' trip. In the company of my shipmates I came up the gangplank with heavy heart, light suitcase, and donkey's breakfast. Stepping or staggering aboard, we were given musical honours, the Laurel and Hardy theme song played on the squeezebox by a fat boy from Hull (Albert Gomersall, where are you now?). One of the lads spat and said: 'I see we've joined a floating symphony orchestra'. It turned out that besides Albert's squeezebox we had with us a fiddle, an ocarina, and a mandoline (not played tremolo or tearaway, but with a rather innocent and absorbed deliberation, much as Martin plays it here). Also, we had a vocal harmony group; well, several of them. We'd a lot of Welshmen aboard, from Holyhead and Amlwch, mostly small fellows destined for the liver-gang. They sang all the time: hymns. Nelson Eddy numbers. Just before the battle, mother. If two met, they sang in harmony. If one was on his own, like as not he'd sing just a harmony part — the bass of the piece, or an alto line. On the way down to the ice, some of the Englishmen went nearly scatty, chipping rust or, worse, cleaning oil-tanks (they boom like a cathedral) all day alongside a Welshman who never let up on The Indian Love Call, but sang round the tune all the time and never came out with the melody. In self-defence, some of us English also took to singing in parts, often without blend, but we found it thrilling. At foc'sle sing-songs we mostly sang film-hits or Victorian and Edwardian tear-jerkers; only a few whaling songs — Greenland Bound, The Diamond (Tich Cowdray's special). The Balaena (many of the lads knew that one), and — of course — Off to Sea Once More. One night in the Antarctic when the whales were scarce, we gave a concert over the ship's wireless, for the benefit of any other factory-ships or catcher-boats in our neighbourhood. There was a lot of weather blowing, and it's doubtful if anyone was picking us up (perhaps some nearby Japanese?), but in that bloodstained ship we imagined ourselves to be radio stars throwing our voices on a spangled wind, and it was a memorable night for us. I like to think the sound we made was a bit similar to what you hear on this record.

A. L. Lloyd

The Balaena — One of the best-known whaling songs, perhaps because it was made relatively late in the history of the trade. Dundee was specially interested in whaling because her main industry, the jute manufacture, required whale oil. In 1873, the Dundee whaling fleet consisted of ten vessels, all equipped with steam power. Largest and proudest was Mr. R. Kinnes's Balaena, of 260 tons register, length 141 ft., with engines of 65 h.p. At that time, the fleet would leave Scotland during the first half of May, race across to Cape St. John, Newfoundland, then northabout into the Davis Strait and the right-whale grounds of Melville Bay on the northwest coast of Greenland. Around August they would be following the southerly migration of the whales to the Cumberland Sound on the east side of Baffin Land. With luck, by early November they would be back in Dundee, exulting over their success, like the men of the nuggetty old Balaena who made this song.

The Coast of Peru — By no means all the oldtime whaling was done in northern waters. In the 1820s, for example, more than a hundred British ships, mostly out of Hull or London, were fishing in the spermwhale grounds round the Horn off the coast of Chile and Peru and taking the long, long run across the Pacific by way of Galapagos Island and the Marquesas, to Timor. The trip would last three years. The Coast of Peru is the most important ballad of the South-Seamen. Possibly it describes the chase of a southern right whale, not a sperm. Sperms were usually harpooned by running the boat close to the whale. Right whales, who tended to fight with their tail, were more often harpooned with the 'long dart' from perhaps ten yards away. Mention of the mate 'in the main chains' dates the song before the 1840s.

Greenland Bound — When the ships left London, Hull, Dundee for the northern grounds, the yards would decorated with ribbons snatched from any pretty girls venturing near the quay, and the men would sing on the maindeck till the harbour bar was passed. They would put in at the Orkneys or Shetlands to take on fresh provisions and water, and perhaps a man or two to complete the crew, and then off to the cold coast of Greenland. This tender farewell song was a favourite of Fred Clausen, a meat-cutter aboard the Southern Empress, and native of Stoneferry, Hull. Its elegiac tone suggests it was made by a Scottish whalerman (English whale-balladeers generally inclined to rough adventure or outspoken complaint). John Ord, folk song collector and superintendent of police, heard the melody, or something very like it, sung by fisher-girls in north-east Scotland in the 1880s.

The Weary Whaling Grounds — Three emotions dominated the oldtime whalerman: exultion in the chase, a longing for home, and disgust at the conditions of his trade. This latter mood descended heaviest upon him when the fishing was poor and he became 'whalesick' (like homesick, only sick for whales). The man who made the complaint of The Weary Whaling Grounds must have been very whalesick. An odd point: the song speaks of leaving 'old Greenland's icy grounds' and indicates a trip of four years' duration. The very long trips only occurred in the Southern fishery; the Greenland season was usually but a matter of months, though ships sometimes stayed all winter at the entrance to the Davis Strait so as to make an early start next season.

The Cruel Ship's Captain — Early in the nineteenth century, a whale skipper was charged in King's Lynn with the murder of an apprentice. A broadside ballad, in the form of a wordy gallows confession and good night, appeared, and in course of circulating round the East Anglian countryside it got pared down to the bone. The poet George Crabbe was interested in the case, and took it as a model for his verse-narrative of 'Peter Grimes', which subsequently formed the base of Britten's opera. The opera is in three acts. The same ground is covered in three verses by a song as bleak and keen as a harpoon head.

Off to Sea Once More — Estimable Stan Hugill says this song is 'known to every seaman'. Well, to a good few, anyway. Who was Rapper Brown, the villain of the piece? Particularly during the latter days of sail, many lodging house keepers encouraged seamen to fall in debt to them, then signed them aboard a hardcase ship in return for the 'advance note' loaned by the company to the sailor ostensibly to buy gear for the voyage. Paddy West of Great Howard Street, Liverpool, was well-known for this, likewise John da Costa of the same seaport. But we do not find a Rapper Brown in this rogues' gallery. Perhaps there's some confusion here with the fearsome Shanghai Brown of San Francisco, through whose ministrations many a British seaman awoke from a drunken or drugged sleep to find himself aboard a vessel bound for the bowhead whaling grounds of the Bering Sea, a trip few men in their senses signed for, unless desperately hard pushed. Our version is from Ted Howard of Barry.

The Twenty-third of March — As long ago as 1725, the dock at Deptford, in south-east London, was used as a whale depot by the South Sea Company, whose interests extended as far north as Spitzbergen. To this day it is called the Greenland Dock, and it is named in many good songs. We do not know how old this particular song is, which W. P. Merrick obtained from the Lodsworth, Sussex, farmer Henry Hills around 1900. It follows a familiar pattern of whaling songs: departure, hard times on the grounds, rowdy return. The old description of the whaleman: 'head of iron and heart of gristle' well fits the anonymous characters of this piece, who can defy weather bitter enough to freeze off your finger-tips and toe-nails.

The Bonny Ship the Diamond — Sad events lie behind this most spirited of whaling songs. By the 1820s the relatively milder northern waters were fished clean, and whalemen were having to search in more distant corners of the Arctic, notably round the mighty and bitter Melville Bay in Northwest Greenland. In 1830, a fleet of fifty British whaleships reached the grounds in early June, a month before they expected. But the same winds that had helped them, also crowded the Bay with icefloes, and locked most of the fleet in, including the Diamond, the Resolution, the Rattier (not Battier) of Leith (not Montrose), and the Eliza Swan. Twenty fine ships were crushed to splinters, and many bold whalerman froze or drowned. The Eliza Swan was among those that got free and brought the sad news home. Our song must have been made only a season or two before that tragedy, for the Diamond's maiden voyage was only in 1825. One wonders if the man who made the song was up in Melville Bay, the year of the disaster, and whether he was lost with his ship.

Talcahuano Girls — The song called Spanish Ladies was on the go among seamen in Samuel Pepy's day, but by the 1840s, Captain Marryat (author of Midshipman Easy) reported it as 'now almost forgotten'. Nevertheless it survived well in countless parodies (one of them associated with Australian drovers, as it happens). The present version belongs to the rowdy South-Seamen who, particularly during the first half of the nineteenth century, sailed out of London and Hull to hunt the sperm whale off the coasts of Chile and Peru. Talcahuano lies south of Valparaiso in Chile; Huasco is about midway between 'Vallypo' and Antofagasta; Tumbez is on the Gulf of Guayaquil, near the Equator: odorous ports, all three.

Farewell to Tarwathie — The stereotype of the oldtime whaleman is of a hairychested ring-tailed roarer, hard worker, hard drinker, hard fighter. No doubt the description fitted many of them; nevertheless they often showed strong liking for gentle meditative songs. Perhaps alone among all the songs on this record. Farewell to Tarwathie was made not by a whaleman but by a miller, George Scroggie of Federate, near Aberdeen, around the middle of the nineteenth century. The tune is an old favourite, best known in connection with the song called The Green Bushes.

Rolling Down to Old Maui — Maui is one of the Hawaiian islands. In the fifties and sixties, the Pacific whalers used to meet there, or in nearby Oahu, twice a year. In March they fitted out for the summer season in the Arctic, when they fished the bowhead grounds off Kamchatka and the Gulf of Anadyr. In November, they were back again, to fit out for sperm-whaling in the tropical and subtropical waters of the Southern Seas. Hence this song, bidding farewell to the bitter North, and looking forward with a smile to the languors of the South.

The Greenland Whale Fishery — This is the oldest — and many think the best-of surviving songs of the whaling trade. It had already appeared on a broadside around 1725, very shortly after the South Sea Company decided to resuscitate the then moribund whaling industry, and sent a dozen fine large ships up to fish around Spitzbergen and the Greenland Sea. The song went on being sung with small changes all the time to bring it up to date. Our present version mentions the year 1834, the ship Lion, its captain Randolph. Other versions give other years, and name other ships and skippers (there was a whaler the Lion, out of Liverpool, but her captain's name was Hawkins, and she was lost off Greenland in 1817). We may take it that the incident described in the song is not historical but imaginary, a stylization like those thrilling engravings of whaling scenes that were once so popular. But the song's pattern of departure, chase, and return home, was imitated in a large number of whaling ballads made subsequently. It is the ace and deuce of whale songs.

Paddy and the Whale — From the latter days of whaling, this jokey remake of the Jonah legend. South Georgia lies east of Cape Horn, towards the fringes of the Antarctic. Till recently there was a land station there, to which the whales were brought for flensing and processing. Presumably Paddy and the Whale originated late in the nineteenth century, though it's debatable whether it was a sea-song first and a stage-song after, or t'other way round. Irish stage comedians knew it, and perhaps it was one of them who set the words to the tune of The Cobblers' Ball.

The Whaleman's Lament — Every crew has its notorious moaner, and in whale-ships when the whales are scarce the number of moaners multiplies. Not that there wasn't plenty to moan about, especially for the men engaged in the Southern whaling round Cape Horn and up the wet and blusterous coast of Chile. Long voyages, stale food, vast stretches of boredom punctuated with brief frenzied and perilous bursts of action; as the lyric says: 'The pleasures are but few, my boys, on them bitter whaling grounds'. This song comes from some time between the 1820s and '40s.

The Eclipse — In the year of Queen Victoria's jubilee, 1887, the steamer Eclipse of Stonehaven went fishing in the Arctic with her sister ships the Erik and the Hope. Her captain, David Gray, was one of the greatest of nineteenth century whaling skippers. By now the northern waters were nearly fished clean of right whales, and the Scottish fleet was taking whatever it could — white whales, narwhals, bottlenoses (David Gray was the first hunter of the bottlenose whale). The 1887 season was disastrous. The Erik caught one small whale, the Hope none at all. On June 21st, Davie Gray took a good fat 57-foot cow whose jawbones are still on show in London's Natural History Museum, but even the Eclipse, that luckiest of whalers, came home light, and with a bonus of only one-and-threepence a ton for oil. Her crew felt the trip had hardly been worth the hardship, and they marched through the streets of Peterhead to tell the owners so. The Eclipse made her first voyage in 1867. When she finished whaling, she was sold to the Russians and, renamed the Lomonosov, she was still being used as a survey ship along the Siberian coast as late as 1939.