|

|

Perhaps rather grandiloquently, the name 'revivalist interpreter' has been applied to those singers, often from urban backgrounds themselves, who seek to recreate traditional song in the most beautiful and expressive and fitting style of all — which is the style of the country singers who themselves moulded the songs.

Such singers are often first influenced these days by the major British revivalists, A. L. Lloyd and Ewan MacColl. Through their work, younger singers have been led to explore the rich heritage of song available through recordings of traditional singers and the collections made in Britain in this century.

So the 'second generation' has begun to create, in its turn, a style of singing that is rooted in the tradition but also synthesises various other elements to which, they have been exposed. Where there is no directly inherited tradition, a singer must perform this act of synthesis on the sources available to him.

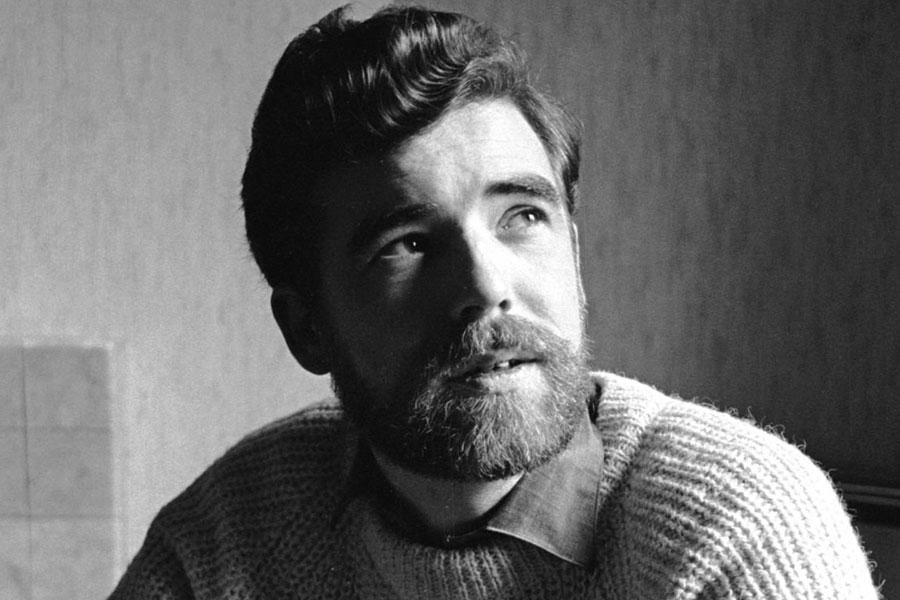

This is what Louis Killen, best of the singers of the second generation has done. Born in Gateshead-on-Tyne in 1934, he comes of a singing family; singing sessions were the major form of family entertainment in his childhood. But it was not until his late teens that he consciously became aware of 'folksong', and not until 1957, when he was associated with a group of traditional song enthusiasts in Oxford, did he become aware of the full artistic force of the folksong of this country. In 1958, he helped to form 'Folksong and Ballad, Newcastle' now one of the most important clubs in Britain where traditional song is authentically performed. Since then, his own work has become more and more a living act of recreation.

For the last few years, he has been making a living by singing folksongs in clubs, on radio, television and in concerts and has gained a national reputation without making any concessions whatsoever to commercialism in his manner of performance.

He has developed an unusually subtle and sensitive accompanied singing style, to match a repertoire of the grand and vigorous story songs and love songs from the English countryside, some of which are represented on this record, the first L.P. devoted to his solo singing, although Topic have widely featured him on anthology records and E.P. records.

He has also fruitfully explored the potential of the English, concertina in folksong accompaniment; two examples of his singing with concertina are given here.

Paradoxically, he stamps each performance with his own musical individuality and dynamism through keeping to the disciplines of traditional singing, a paradox which is the basis of the serious folksong revival.

Young Edwin In The Lowlands — Usually, folksongs tell of a sailor's joyful homecoming, with a happy welcome from the girl he left behind; but Young Edwin's welcome is the cold steel of a sword blade. The girl's cruel parents murder the returned wanderer because his pockets are lined with gold. A favourite of the broadside printers, who knew a good melodrama when they saw one, this ballad has travelled to Canada and the U.S.A. This version is substantially that which Ralph Vaughan Williams collected in Hampshire in 1907; it is printed in The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs, Ralph Vaughan Williams and A. L. Lloyd, 1959.

As We Were A-Sailing — Other versions of this stirring sea battle song fill in the details. The dauntless heroine was able to take command so opportunely when the captain was killed in battle because she had dressed up as a man to follow her true love to sea, and as one Canadian variant has it:

She served for twelve long months all with her jolly tars

Till at length she had learned the arts of man o' war.

Although they are related to the Amazons of classical legend, those ferocious ladies who amputated a breast the better to draw a bow, the warlike young women so familiar in folksong and folklore were by no means non-existent in real life. John Ashton, in Modern Street Ballads, London 1888, quotes an instance from no less veracious a source than The Times for November 4, 1799. It seems that a certain Miss Talbot followed her lover as a seaman but joined the army in a fit of pique after she quarrelled with him. But her love of the sea was unconquerable and she joined the Navy, being present on board Earl St. Vincent's ship of February 14, and again was under fire at Camperdown.' Frank Kidson collected this fine version in Yorkshire and printed it in his Traditional Tunes, Oxford 1891. Kidson thought the girl's ship was called The Rainbow due to some relationship between this song and the ballad about the Elizabethan pirate, Captain Ward, called A Famous Sea Fight between Captain Ward and the Rainbow. Percy Grainger found similar sets in Lincolnshire; the song has often been found in the British tradition in differing forms.

The Flying Cloud — There was nothing of the rakish, jolly, romantic pirate of pantomime and nursery lore about the real lives of the brutal criminals of the high seas who flourished in the early nineteenth century and before. Despite its beautiful name, The Flying Cloud was such a pirate vessel, if not in reality — for no record has come to light of a pirate ship called The Flying Cloud — then in the imaginations of scores of traditional singers. T his harsh and violent ballad, cast in the form of a confession from the gallows, depicts the worst of piracy on the Atlantic and the Caribbean in the early 1800s, when piracy and the slave trade often went hand in bloody hand. Doerflinger (Shantymen and Shantyboys, New York, 1951) suggests the ballad-makers were originally inspired by a pamphlet, The Dying Declaration of Nicholas Fernandez, the purported confession of a notorious pirate on the eve of his execution in 1829 — curiously enough, published as a temperance tract. The song is widely known in North America as well as in Britain. In Nova Scotia, the collector Elizabeth Greenleaf observed the tremendous emotional impact it made on audiences at singing gatherings in the nineteen twenties. At one time, it was an especial favourite with landlubbers in Canadian lumber camps. Most versions are broadly similar in text and tune.

All Things Are Quite Silent — Speaking more truly than he knew, Melville's Billy Budd cried out: 'Farewell, old Rights of Man!' as the press gang rowed him from the merchant vessel, The Rights of Man and its kindly master to the grim privations of a Royal Navy man o' war. To maintain the crews inside the 'wooden walls of Old England' in the hellish conditions below decks, press-gangs forced men where there were no volunteers and wives and sweethearts were left behind to mourn. This lament of a deserted wife seems to have been collected only once in the British tradition — by Vaughan Williams, in Sussex in 1904. It is the first song in The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs. The haunting first verse, where the press-gang breaks in on a scene of idyllic peace and tranquillity, recalls the more familiar ballad, The Lowlands of Holland. There the press-gang unceremoniously snatch a man from his marriage bed. But the stoic dignity of the wife in All Things are Quite Silent is in marked contrast to the violent grief of the other girl.

One May Morning — In the eternal springtime of English love songs, a girl tries to fend off the advances of an importunate young man by telling him that she is too young; but he proves to her the truth of the cruel old saying, when they're big enough, they're old enough'. Told from the point of view of the girl who, as in one American version, later brings forth a little baby boy after the statutory nine months — 'and me not fifteen years of age', the song can be intolerably poignant; most versions, though, arc as emphatically masculine as this bawdy guffaw. Hammond collected this treatment of a widespread theme in Dorset in the early years of the century, but it was deemed sufficiently indelicate to bring a blush to Edwardian checks and was duly doctored for publication. This is how Hammond heard it first of all.

The Cock — This frank and warm-hearted love-song is one of the well-known group of 'night visiting songs'. As in many of these songs, and in the aubades of the troubadour poets of the middle ages, the crowing of a cock signals the passing of time and the parting of the lovers. In some of this song's relations, notably the ballad The Grey Cock, cock-crow has a supernatural significance; it summons a dead lover back to his grave after a last night with, a living true love. But here, it breaks the embraces of earthly lovers and the young man trudges off over the cold fields, thinking ruefully of his girl in her snug bed. Hammond found sets of this song in Dorset, one of which is printed in A Dorset Book of Folk Songs, Brocklebank and Kindersley, London 1948.

The Bramble Briar — Country singers have titled this passionate old ballad Bruton Town, The Brakes o' Briar and, oddly, Strawberry Town. John Keats called the narrative poem he made out of the same story, Isabella and the Pot of Basil. But the story itself may not have been new when Bocaccio first set it down in writing in the fourteenth century. Hans Sachs also liked the story and put it into verse a couple of centuries after Bocaccio's prose. So the theme has certainly not been without its share of literary admirers. But perhaps the stark language of balladry suits it best of all. The ballad is not included in F. J. Child's compendium. Some scholars think it was translated directly from the Italian of the Decameron into English broadside verse, perhaps in the seventeenth century. Versions have appeared in print this century from Somerset and Hampshire, usually with tunes of startling beauty. This tune comes from a Mrs. Joiner of Hertfordshire, who learned most of her songs when, as a little girl, she went to a 'plaiting school' where she and her friends exchanged songs and stories as they plaited straw, later to be made into straw hats. (They learned to read in between times.) This tune and a partially collated text are printed in The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs.

Thorneymoor Woods — Poachers held a place of high esteem in the imagination of country people. The late George Maynard of Sussex had a large number of songs detailing the heroic exploits of poachers in his repertoire — not, perhaps, surprisingly, since he had been something of an expert in the art himself, in his youth. Like true heroes, most poachers bravely face up to misfortune in these songs — whether it is the murderous spite of gamekeepers, or a trip to the county gaol. This epic story of a night's poaching was learnt, not from Maynard but from an even finer singer, Harry Cox of Catfield, Norfolk, and has a certain quality of tough independence which is part of Cox's immensely virile singing. In spite of its Nottinghamshire locale, the song has been reported from several parts of the country. The cheerful defiance of the unrepentant hero probably accounts for its popularity.

The Banks Of Sweet Primroses — This bittersweet love-song, perhaps of seventeenth century broadside origin, remains remarkably constant in text and tune whether sung in Sussex, Somerset, the Gower peninsula or the North Country, or put into the homemade harmonies of the Copper Family again in Sussex. As A. L. Lloyd says: "Clearly, singers have found this song unusually memorable and satisfactory, for the process of oral transmission seems to have worked little change on it." (The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs.) Like so many English love songs, the opening magically recalls the breathless evocation of spring in medieval poetry, when leaves grow green, flowers bud out, small birds sing and the young man says: 'Now springes the spray. All for love I am so sick That slepen I ne may.