|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

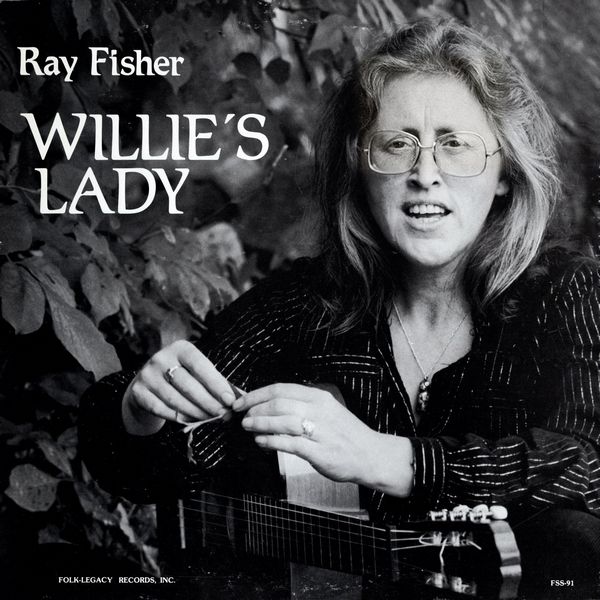

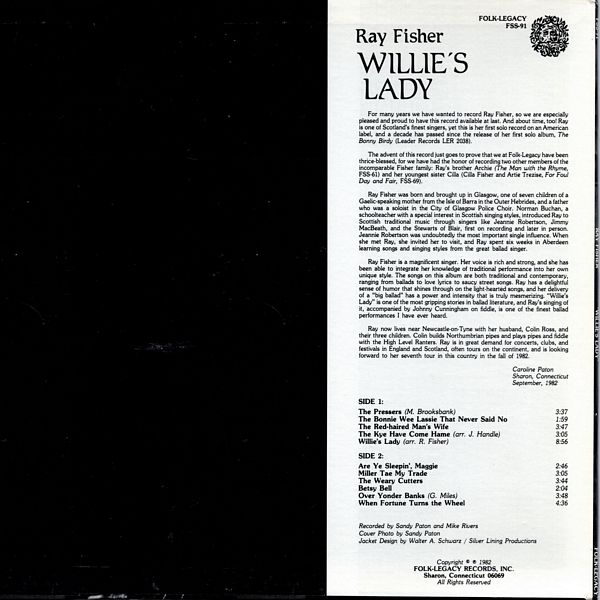

For many years we have wanted to record Ray Fisher, so we are especially pleased and proud to have this record available at last. And about time, too! Ray is one of Scotland's finest singers, yet this is her first solo record on an American label, and a decade has passed since the release of her first solo album, The Bonny Birdy (Leader Records LER 2038).

The advent of this record just goes to prove that we at Folk-Legacy have been thrice-blessed, for we have had the honor of recording two other members of the incomparable Fisher family: Ray's brother Archie (The Man with the Rhyme, FSS-61) and her youngest sister Cilia (Cilia Fisher and Artie Trezise, For Foul Day and Fair, FSS-69).

Ray Fisher was born and brought up in Glasgow, one of seven children of a Gaelic-speaking mother from the Isle of Barra in the Outer Hebrides, and a father who was a soloist in the City of Glasgow Police Choir. Norman Buchan, a schoolteacher with a special interest in Scottish singing styles, introduced Ray to Scottish traditional music through singers like Jeannie Robertson, Jimmy MacBeath, and the Stewarts of Blair, first on recording and later in person. Jeannie Robertson was undoubtedly the most important single influence. When she met Ray, she invited her to visit, and Ray spent six weeks in Aberdeen learning songs and singing styles from the great ballad singer.

Ray Fisher is a magnificent singer. Her voice is rich and strong, and she has been able to integrate her knowledge of traditional performance into her own unique style. The songs on this album are both traditional and contemporary, ranging from ballads to love lyrics to saucy street songs. Ray has a delightful sense of humor that shines through on the light-hearted songs, and her delivery of a "big ballad" has a power and intensity that is truly mesmerizing. "Willie's Lady" is one of the most gripping stories in ballad literature, and Ray's singing of it, accompanied by Johnny Cunningham on fiddle, is one of the finest ballad performances I have ever heard.

Ray now lives near Newcastle-on-Tyne with her husband, Colin Ross, and their three children. Colin builds Northumbrian pipes and plays pipes and fiddle with the High Level Ranters. Ray is in great demand for concerts, clubs, and festivals in England and Scotland, often tours on the continent, and is looking forward to her seventh tour in this country in the fall of 1982.

Caroline Paton Sharon, Connecticut September, 1982

Notes on the Songs

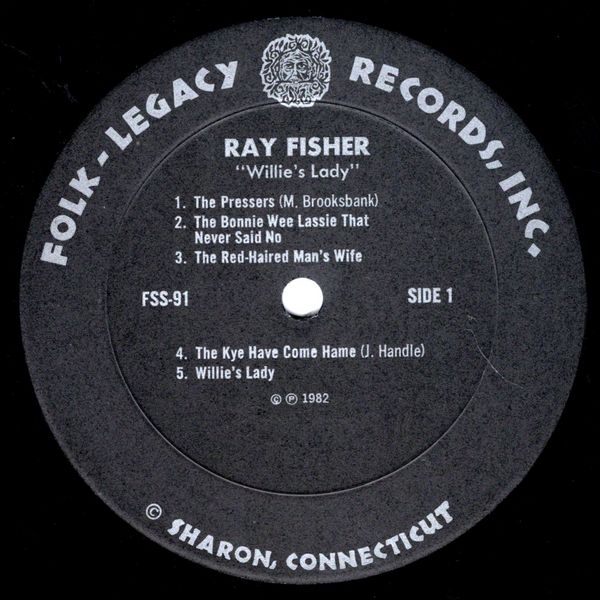

The Pressers — The theme of this press gang song is based on remnants of a traditional song. Mary Brooksbank, of Dundee, composer of the widely-known "Jute Mill Song" (or "Ten and Nine"), added some verses of her own to the existing snippet that she had retained in her memory. The reference to "Boney" (Napoleon Bonaparte) suggests this to be the case. Wee Mary was a bundle of enthusiasm and a joy to listen to.

I recall at an early TMSA* festival in Blairgowrie, Scotland, she enthralled everyone with her songs and poems of love, work and politics. She was one of the quiet giants, although she stood just over five feet tall.

(*TMSA — Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland)

The Bonnie Wee Lassie That Never Said No — A fine song from the singing of Jeannie Robertson. There are many songs, sung mainly by men, about young women outwitting them — this one redresses the balance a little. I feel the tune of this song has an Irish flavor.

The Red-Haired Man's Wife — Here is a song that sums up all the anguish, emotion, and controlled anger of unrequited love. I had heard Kevin Mitchell, from Ireland, now living in Glasgow, sing this song many times in the purest tenor voice ever. I loved the song and tune dearly. About two years ago, Kevin decided to sing it to a different 'air.' The 'new' tune was a fine one, but I much preferred the other 'old' tune. I have taken the liberty of singing Kevin's original combination — for fear I'll forget it.

No chance!!

The Kye Have Come Hame — Johnny Handle, front man in the High Level Ranters, also took an existing traditional verse and added additional words to create a touching song of a missing child. The tune is known in Northumberland as "Felton Lonnen" and suits the new text admirably. I have changed some of his words — he sang "hinny" where I have "laddie." "Hinny" is the affectionate Geordie term meaning "honey" or "dear one." The Geordie words are very close in meaning and pronounciation to those used in Scotland. This song brings a lump to my throat when I sing it!

Willie's Lady — I have set this magnificent ballad to the tune of a Breton drinking song — I've no idea what it's called. The text is based entirely on the contents in Francis James Child's massive collection, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. I have omitted, added, and "telescoped" some of the verses.

For immediate understanding, the plot is as follows: Willie marries a young and beautiful girl. His mother, a witch, disapproves of the girl and curses her. The girl will never produce a child; she and the child will die in childbirth. Offers of gifts to the mother to lift the curse prove fruitless. Willie seeks and gets help from a servant, the Billy Blind. Willie follows the Billy Blind's instructions and foils his mother's scheme and eventually fathers a son.

The Billy Blind: some Scottish households retained a non-working servant who possessed some disability, e.g., deaf, dumb, hare-lipped or blind. The belief was held that they had second-sight, wisdom, or some supernatural power to compensate for their disability. They were feared by many, mainly due to ignorance. A blind man may well develop an extra keen hearing capacity and a refined sense of touch, so the belief was reasonably well-founded. Thus, as a means of protection or insurance against evil, a household would shelter such a person. In this ballad he was blind.

A brief clarification of the curses: the knots in the girl's hair (note the magic number, nine; 3X3 = powerful) symbolize the constricting elements — holding back the free-flowing birth of the child. Even today, in some parts of Scotland, during childbirth a girl's garments are loose, unbuttoned, without pins or fastenings. The combs (kaims o' care) of care were pressed through the long, golden hair, accompanied by a curse each time, and then left in the hair to hold in the curse. The hair is a powerful vehicle for curse-making. The Master kid (a young goat) was the link between the forces of evil and the witch — the catalyst or carrier. This invariably is an animal — the witch's cat being the most widely-known example. The woodbine is a clinging, constricting plant that holds on and winds around other plants and branches — holding in again is symbolized here. Lastly, the left-side shoe (leften shee) again has evil influences (i.e., Latin: sinister).

This was tightly knotted to strengthen the curse. Finally, the advice from the Billy Blind to make a wax baby and invite the mother to the christening is a master stroke indeed. This results in the eventual birth of a son.

Comment: The mother really laid it on pretty heavily with the curses — any one would have done the trick! She must either have doubted her own skills or have feared the power of the love bond between her son and the girl.

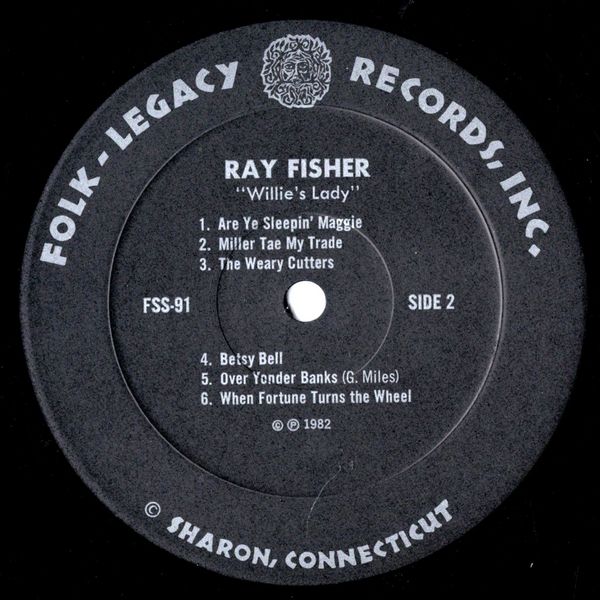

Are Ye Sleepin' Maggie — A song from the Tannahill collection. Marvelous build-up of atmosphere with powerful emotive words which combine with a wonderful tune to produce the finest of our Scottish "night-visiting" songs. I heard Jeannie Robertson sing it a few times, but I didn't learn it directly from her. I confess that I had to consult a book with a glossary to get the full understanding of the text.

Miller Tae My Trade — An outstanding song from the impressive repertoire of Lucy Stewart of Fetterangus, Norman Buchan played me a tape of the song and verbally explained how Lucy produced the watermill wheel sound. The movements that I do are not absolutely the same as Lucy's, but I think the end effect is the same. This type of rhythmic accompaniment is unique — so, too, is Lucy Stewart.

The Weary Cutters — I first heard this song from Mrs. Pat Elliott, of the famous Elliotts of Birtley, Co. Durham. I recall her telling me that she had obtained it with help from Louis Killen. There is a reference made to "The Lousy Cutter" in Bruce & Stokoe's Northumbrian Minstrelsy (1882) containing two verses similar to those in this song. It is a coincidence that in the notes on a tune called "The Wedding o' Blyth," which appears alongside the "Lousy Cutter" text, Bruce and Stokoe describe the aforementioned tune as a "weary" one.

Here we have a strong social comment on the feelings of the ordinary folk towards "press-ganging," and the lengths to which people would go in order to avoid being recruited.

I introduce this song with a single verse which was taken down by Mr. Thomas Doubleday, of Newcastle; he was unable to recover any more of the ballad. Captain John Bover, who died in 1782, had indulged in "harsh and tyrannical measures"(*) in order to furnish the British Navy with "pressed" men.

(*) Quoted from Northumbrian Minstrelsy

Betsy Bell — I learned this song from Jeannie Robertson. She would sing "Fit's a dae" in her Aberdeenshire tongue, meaning directly in English "What is to do?" This phrase is translated as "What is the matter?" In this case she is condemning the local male population for their lack of attention to her. Whenever Jeannie sang this wee song, she'd pick out some poor, innocent male listener and sing directly to him, and he would blush with embarrassment.

Over Yonder Banks — This is a recently written song, sent to me by the composer, Graeme Miles of Middlesborough, Teesside, England.

All of Graeme's songs have a mark of pure and sincere simplicity. Here he recalls his youth and his hometown environment and says that it takes more than bulldozers to erase the memories that have been re-awakened on a return visit to the playground of his youth.

On my return visits to Glasgow, I feel just this way.

When Fortune Turns The Wheel — I first heard Louis Killen, of Gateshead, Co. Durham, sing this song. His version had come from Alan Rogerson of Northumberland and had a "south of the border" flavour. I subsequently gleaned the Scottish text from Greig's Folksongs of the Northeast" which was remarkably similar in tune and content, but varied only in local references, i.e., place-names, etc. This is one of the great parting songs.