|

|

|

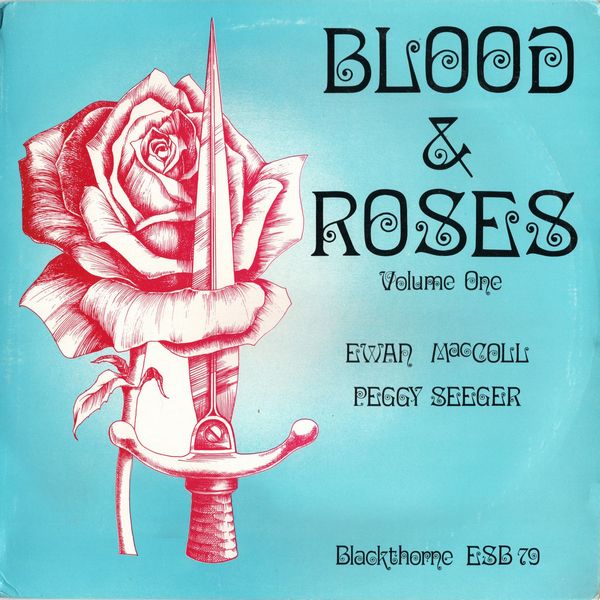

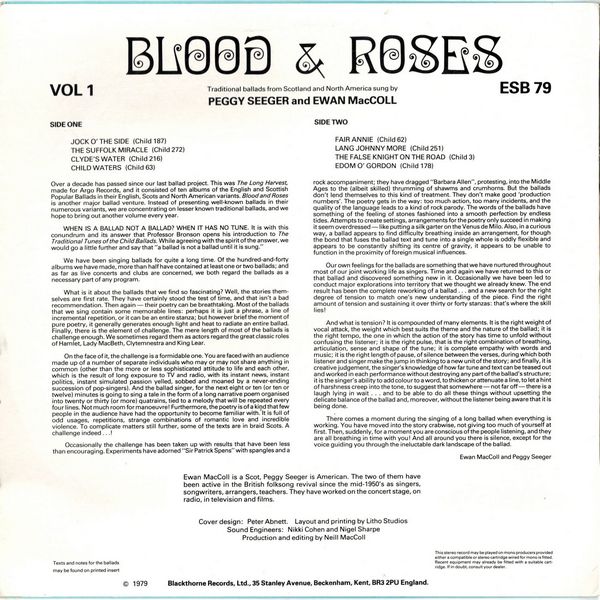

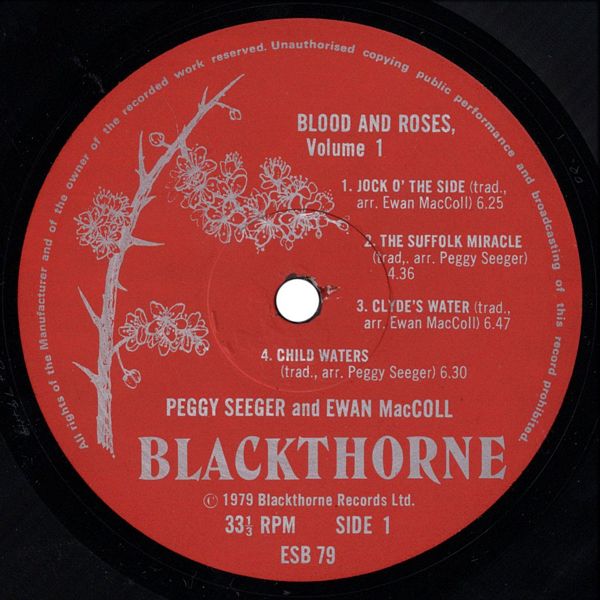

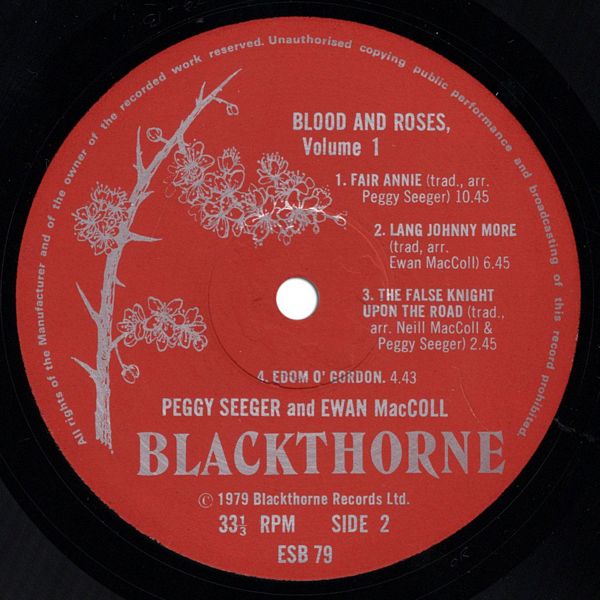

Sleeve Notes

Traditional ballads from Scotland and North America sung by PEGGY SEEGER and EWAN MacCOLL

Over a decade has passed since our last ballad project. This was The Long Harvest, made for Argo Records, and it consisted of ten albums of the English and Scottish Popular Ballads in their English, Scots and North American variants. Blood and Roses is another major ballad venture. Instead of presenting well-known ballads in their numerous variants, we are concentrating on lesser known traditional ballads, and we hope to bring out another volume every year.

WHEN IS A BALLAD NOT A BALLAD? WHEN IT HAS NO TUNE. It is with this conundrum and its answer that Professor Bronson opens his introduction to The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads. While agreeing with the spirit of the answer, we would go a little further and say that "a ballad is not a ballad until it is sung."

We have been singing ballads for quite a long time. Of the hundred-and-forty albums we have made, more than half have contained at least one or two ballads; and as far as live concerts and clubs are concerned, we both regard the ballads as a necessary part of any program.

What is it about the ballads that we find so fascinating? Well, the stories them-selves are first rate. They have certainly stood the test of time, and that isn't a bad recommendation. Then again — their poetry can be breathtaking. Most of the ballads that we sing contain some memorable lines: perhaps it is just a phrase, a line of incremental repetition, or it can be an entire stanza; but however brief the moment of pure poetry, it generally generates enough light and heat to radiate an entire ballad. Finally, there is the element of challenge. The mere length of most of the ballads is challenge enough. We sometimes regard them as actors regard the great classic roles of Hamlet, Lady MacBeth, Clytemnestra and King Lear.

On the face of it, the challenge is a formidable one. You are faced with an audience made up of a number of separate individuals who may or may not share anything in common (other than the more or less sophisticated attitude to life and each other, which is the result of long exposure to TV and radio, with its instant news, instant politics, instant simulated passion yelled, sobbed and moaned by a never-ending succession of pop-singers). And the ballad singer, for the next eight or ten (or ten or twelve) minutes is going to sing a tale in the form of a long narrative poem organised into twenty or thirty (or more) quatrains, tied to a melody that will be repeated every four lines. Not much room for manoeuvre! Furthermore, the poetry is of a kind that few people in the audience have had the opportunity to become familiar with. It is full of odd usages, repetitions, strange combinations of romantic love and incredible violence. To complicate matters still further, some of the texts are in braid Scots. A challenge indeed …!

Occasionally the challenge has been taken up with results that have been less than encouraging. Experiments have adorned "Sir Patrick Spens" with spangles and a rock accompaniment; they have dragged "Barbara Allen", protesting, into the Middle Ages to the (albeit skilled) thrumming of shawms and crumhorns. But the ballads don't lend themselves to this kind of treatment. They don't make good 'production numbers'. The poetry gets in the way: too much action, too many incidents, and the quality of the language leads to a kind of rock parody. The words of the ballads have something of the feeling of stones fashioned into a smooth perfection by endless tides. Attempts to create settings, arrangements for the poetry only succeed in making it seem overdressed — like putting a silk garter on the Venus de Milo. Also, in a curious way, a ballad appears to find difficulty breathing inside an arrangement, for though the bond that fuses the ballad text and tune into a single whole is oddly flexible and appears to be constantly shifting its centre of gravity, it appears to be unable to function in the proximity of foreign musical influences.

Our own feelings for the ballads are something that we have nurtured throughout most of our joint working life as singers. Time and again we have returned to this or that ballad and discovered something new in it. Occasionally we have been led to conduct major explorations into territory that we thought we already knew. The end result has been the complete reworking of a ballad … and a new search for the right degree of tension to match one's new understanding of the piece. Find the right amount of tension and sustaining it over thirty or forty stanzas: that's where the skill lies!

And what is tension? It is compounded of many elements. It is the right weight of vocal attack, the weight which best suits the theme and the nature of the ballad; it is the right tempo, the one in which the action of the story has time to unfold without confusing the listener; it is the right pulse, that is the right combination of breathing, articulation, sense and shape of the tune; it is complete empathy with words and music; it is the right length of pause, of silence between the verses, during which both listener and singer make the jump in thinking to a new unit of the story; and finally, it is creative judgment, the singer's knowledge of how far tune and text can be teased out and worked in each performance without destroying any part of the ballad's structure; it is the singer's ability to add colour to a word, to thicken or attenuate a line, to let a hint of harshness creep into the tone, to suggest that somewhere — not far off— there is a laugh lying in wait … and to be able to do all these things without upsetting the delicate balance of the ballad and, moreover, without the listener being aware that it is being done.

There comes a moment during the singing of a long ballad when everything is working. You have moved into the story crabwise, not giving too much of yourself at first. Then, suddenly, for a moment you are conscious of the people listening, and they are all breathing in time with you! And all around you there is silence, except for the voice guiding you through the ineluctable dark landscape of the ballad.

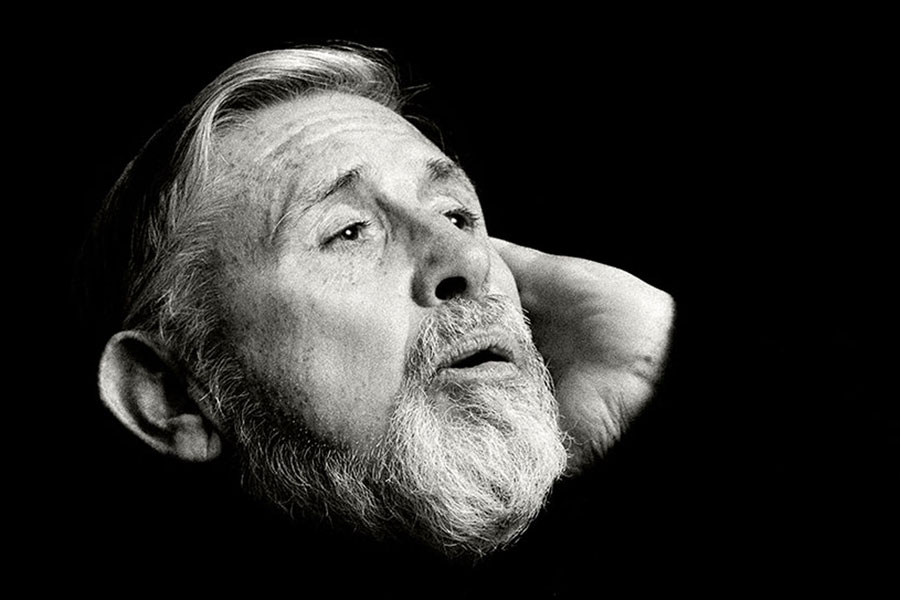

Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger

Ewan MacColl is a Scot, Peggy Seeger is American. The two of them have been active in the British folksong revial since the mid-1950's as singers, songwriters, arrangers, teachers. They have worked on the concert stage, on radio, in television and films.

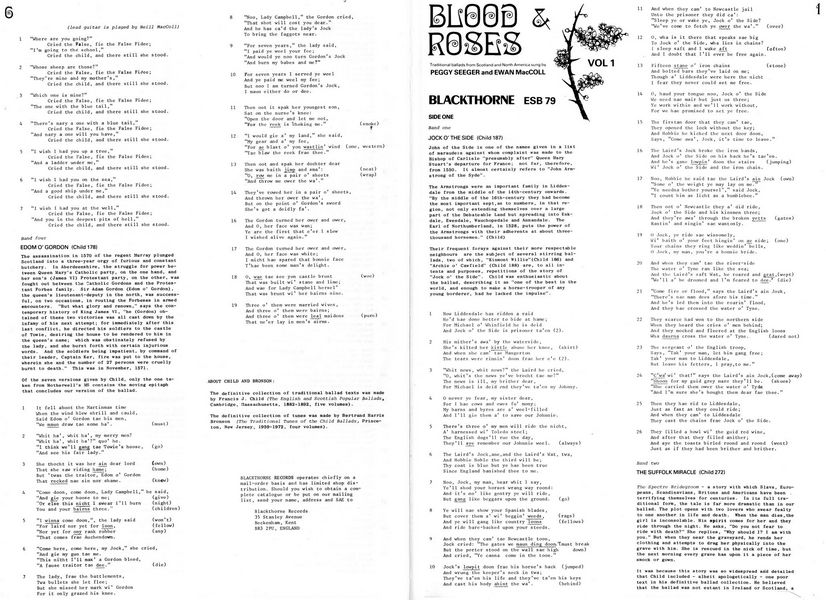

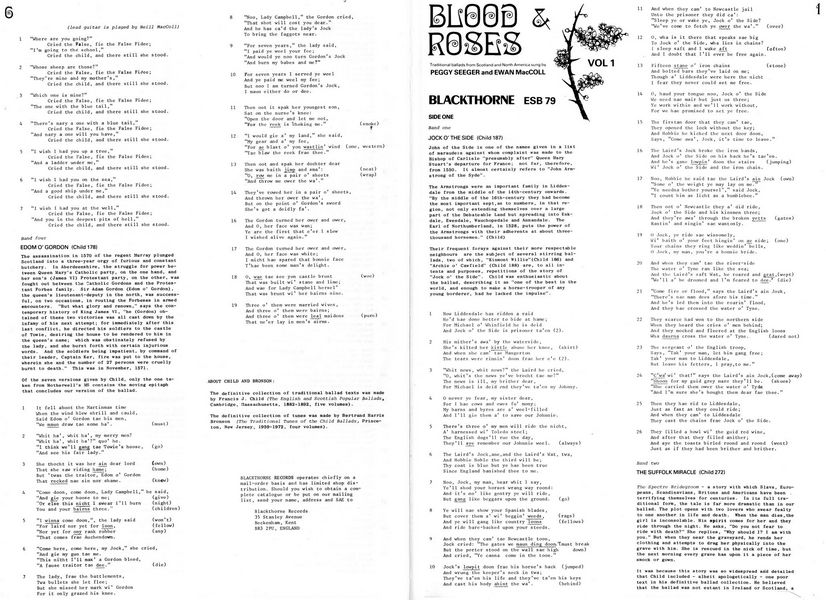

Jock O' The Side (Child 187) — John of the Side is one of the names given in a list of marauders against whom complaint was made to the Bishop of Carlisle "presumably after" Queen Mary Stuart's departure for France; not far, therefore, from 1550. It almost certainly refers to "John Armstrong of the Syde". The Armstrongs were an important family in Liddesdale from the middle of the 14th-century onwards.

"By the middle of the 16th-century they had become the most important sept, as to numbers, in that region, not only extending themselves over a large part of the Debateable Land but spreading into Eskdale, Ewesdale, Wauchopedale and Annandale. The Earl of Northumberland, in 1528, puts the power of the Armstrongs with their adherents at about three-thousand horsemen." (Child)

Their frequent forays against their more respectable neighbours are the subject of several stirring ballads, two of which, "Kinmont Willie"(Child 186) and "Archie o' Cawfield" (Child 188) are, to all intents and purposes, repetitions of the story of "Jock o' the Side". Child was enthusiastic about the ballad, describing it as "one of the best in the world, and enough to make a horse-trooper of any young borderer, had he lacked the impulse".

The Suffolk Miracle (Child 272) — The Spectre Bridegroom — a story with which Slavs, Europeans, Scandinavians, Britons and Americans have been terrifying themselves for centuries. In its full traditional form, the tale is far more dramatic than in our ballad. The plot opens with two lovers who swear fealty to one another in life and death. When the man dies, the girl is inconsolable. His spirit comes for her, and they ride through the night. He asks, "Do you not fear to ride with death?" She replies, "Why should I? I am with you." But when they near the graveyard, he rends her clothing and attempts to drag her physically into the grave with him. She is rescued in the nick of time, but the next morning every grave has upon it a piece of her smock or gown.

It was because this story was so widespread and detailed that Child included — albeit apologetically — one poor text in his definitive ballad collection. He believed that the ballad was not extant in Ireland or Scotland, a fact since disproved by the memories of American informants. Indeed, the ballad is rarely sung now in Britain, but it flourishes in America and Canada: and for once, the New World is not excising the supernatural motifs. Phillips Barry, the excellent American ballad scholar, traces the "superior" North American variants back to the Scotto-Irish forms and the more informal — perhaps slovenly but very singable — southern versions to the Child broadside. Our text is from Virginia.

In Child's set, the girl dies of horror and remorse. Rarely does she do so in the American texts, where we are usually warned in a moralising verse of the meddlesome habits of old (rich) parents. Occasionally, the final verse is given over to a lament, in which the girl vows to henceforth forswear all mankind.

Clyde's Water (Child 216) — At first glance, this ballad appears to be a reworked version of "The Lass of Roch Royal" (Child 76) with the lovers' roles reversed. The surrogate lover motif, a feature of both pieces, tends to emphasise the similarity: the conversation through closed doors between a lover and an imposter, the rejection of the importunate love and his/her subsequent death by drowning, are all there.

The mother's curse upon her son, however, is what gives "Clyde's Water" its unique character, that and the triumphant cry of Maggie as she drowns at her lover's side.

Child cites ballads with similar themes from Italy and Czechoslovakia.

Child Waters (Child 63) — Professor Child's comment on this ballad has often been quoted. He calls it "this charming ballad, which has perhaps no superior in English and if not in English perhaps nowhere." (This, despite the fact that all his ten sets were reported from Scotland.) The ballad has not been reported from England and is hardly known across the Atlantic, the two main American texts having been collected from Arkansas and North Carolina (our text). Even so, this American variant gives the impression that it has not yet been sung in.

The central theme is the same as that in "Fair Annie": patient Griselda, the long-suffering, usually pregnant heroine who follows her wayward lover, awaiting the reawakening of his dulled affections. The trials he visits upon her, as well as a number of other motifs, are shared with several other ballads.

It is interesting that our anti-hero is not named, for in the British texts he is Child Waters, Lord John, Lord Thomas, Sweet Willie, or just plain Willie. The North Carolina set was taken from the singing of Mrs. Rebecca Gordon of Cat's Head, on Saluda Mountain, Henderson County, N.C. The woman who collected it reported another version, apparently too scandalous to print.

(accompanied by Peggy Seeger on the five-string banjo)

Fair Annie (Child 62) — Despite the fact that most of the American versions are abridged, this ballad comes through as one of the most moving examples of the "patient Griselda" story. My set, from West Virginia, is the longest so far published in the United States.

The ballad runs, as Bronson puts it, "back into the mists, through Scandinavian and German analogues" to (and perhaps past) Le Lai de Freisne, the earliest recorded version of the tale (ca. 1180), but does not appear in the Scots repertory until the late 1700's. The Scots texts are extraordinary. They bring the characters alive with brilliant touches of description and dialogue. In some versions, for instance the new bride is quite harsh toward Annie, proposing that she be driven out into the woods. In others, it is suggested that Thomas should hang for his treatment of Annie. Or, occasionally, his callousness may suddenly shift to incredible love:

Rise up, rise up, my bierly bride,

I think my bed's but cold;

I wouldna hear my lady lament

For your tocher ten times told. (dowry)

The ballad is full of Freudian symbolism, as in the 3 verses in which Annie balances herself as predator a-gainst her seven sons. The ballad is packed with old beliefs and customs. Annie must comb down her hair then braid it up into a crown, for only maidens wore their hair flowing. Annie's identity is revealed in a myriad of ways: through a broken-token exchanged with her sibling, through Annie's playing of harp and virginals, through her actually singing her own story outside the bridal chamber.

Considering that the Scots texts are so rich, so observant of human behaviour, it is amazing that the ballad is scarcely ever encountered in Scotland among either field or revival singers. Indeed, it has not been popular in the United States, although the few texts that have been recovered are spread well over the country. The ballad has adapted well in America. The Injuns (not Lord Thomas) steal Annie away; the banjo is used; Annie comes out onto her front porch, employing a spyglass to see the ship; or

Your hogshead hoops are a-bursting off,

And your wine is running out.

The ballad clearly has enormous appeal. It is nearly eleven minutes long, yet it is short in the performance situation, as bated breath gives background to the voice, the poetry, the symbiosis of singer and listener, as they recreate together, once more, this seemingly improbable love-tale.

Lang Johnny More (Child 251) — In a note to ballad No. 99, Child refers to "Lang Johnny More" as "perhaps an imitation" and in fact almost a parody of "Johnnie Scot." This less than enthusiastic reference to one of the funniest pieces in the entire canon suggests that the professor's ear for the Scots tongue was less than perfect.

While it is true that the plots of "Lang Johnny More" and "Johnnie Scot" are almost identical, the intonation and general tone of the two ballads are poles apart. Johnnie Scot is "as brave a knight as ever sailed the sea". The hair that "hung on his head was like threads of gold". He takes a knightly oat to "relieve the damesel that last lay by my side". He fights a duel with an Italian champion swordsman and wins the liberty of his love. This surely is the language of romance and chivalry.

Lang Johnnie More, on the other hand, is a genial giant who talks like an Aberdeenshire ploughman and who, even on the gallows, cannot bring himself to take his captors seriously. Auld Johnny and Jock o' Noth are two amiable old worthies, still able in their dotage to run from North Aberdeenshire to London in some two-and-a-half days. At the gates of the city, they indulge in no heroics but casually kick a hole in the wall and enter that way. By riding in "by Drury Lane and doon by the toon ha'", they reduce London to a country town of manageable size.

Much of the irony is directed inwards at the Scots' sense of exaggerated self-esteem and at what is sometimes seen as an obsessional national compulsion to deafen the world with assertions of masculinity.

Parody? Perhaps, but if so, the parody is a great deal more interesting than the original model.

The False Knight On The Road (Child 3) — Here we have a truly ancient subject for balladry, folktale and folklore: the conflict between good and evil. The False Fidee is, of course, the devil and the child is teetering on the brink of Hell. The dialogue form is well-established in the tradition, housing classic content in classic form.

Riddling is a time-honoured human occupation. Traditionally, it was practiced at crucial periods in the human life cycle: birth and death, courtship and marriage, sowing and reaping, etc. It has very strong religious and supernatural overtones, even in modern times when riddling is a vehicle not only for mundane affairs or hilariously surrealistic subject matter but also for overt social comment. Riddling was entertainment, but it was also for the instruction of the young,' to help develop a sense of the world, a sense of values and a good wit at the same time.

The ballad was recited as well as sung. It appeared quite regularly in textbooks, yet never became what one might call a "popular piece". Our text, from Indiana, is fairly broken down and could be regarded as a typical American example. It still contains the stark confrontation which renders the older Scandinavian and Scots versions almost as fairy tales; it lacks only the richness of imagery that an old language in an old civilisation confers upon a work of verbal art.

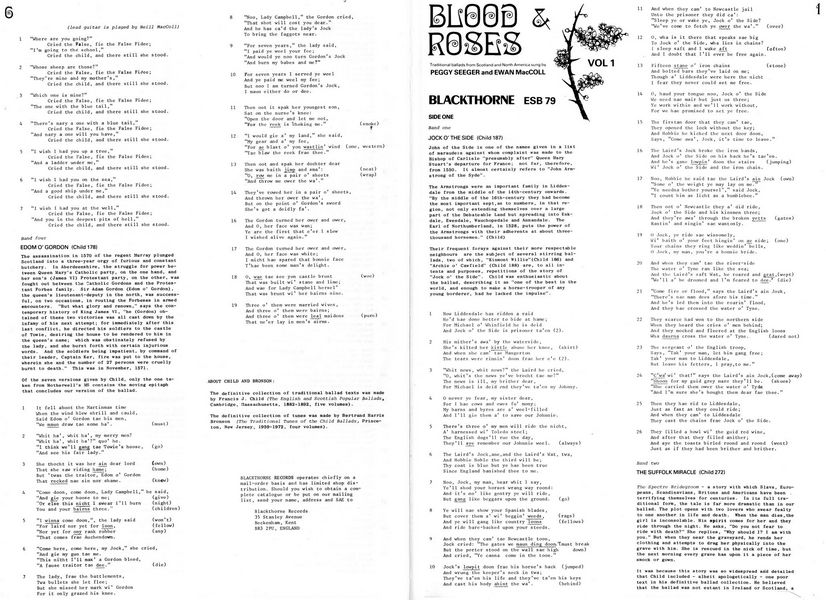

Edom O' Gordon (Child 178) — The assassination in 1570 of the regent Murray plunged Scotland into a three-year orgy of furious and constant butchery. In Aberdeenshire, the struggle for power between Queen Mary's Catholic party, on the one hand, and her son's (James VI) Protestant party, on the other, was fought out between the Catholic Gordons and the Protestant Forbes family. Sir Adam Gordon (Edom o' Gordon), the queen's lieutenant-deputy in the north, was successful, on two occasions, in routing the Forbeses in armed encounters. "But what glory and renown," says the contemporary history of King James VI, "he (Gordon) obtained of these two victories was all cast down by the infamy of his next attempt; for immediately after this last conflict, he directed his soldiers to the castle of Towie, desiring the house to be rendered to him in the queen's name; which was obstinately refused by the lady, and she burst forth with certain injurious words. And the soldiers being impatient, by command of their leader, Captain Ker, fire was put to the house, wherein she and the number of 27 persons were cruelly burnt to death." This was in November, 1571.

Of the seven versions given by Child, only the one taken from Motherwell's MS contains the moving epitaph that concludes our version of the ballad.

About Child and Bronson:

The definitive collection of traditional ballad texts was made by Francis J. Child (The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1882-1892, five volumes).

The definitive collection of tunes was made by Bertrand Harris Bronson (The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads, Princeton, New Jersey, 1959-1972, four volumes).