|

|

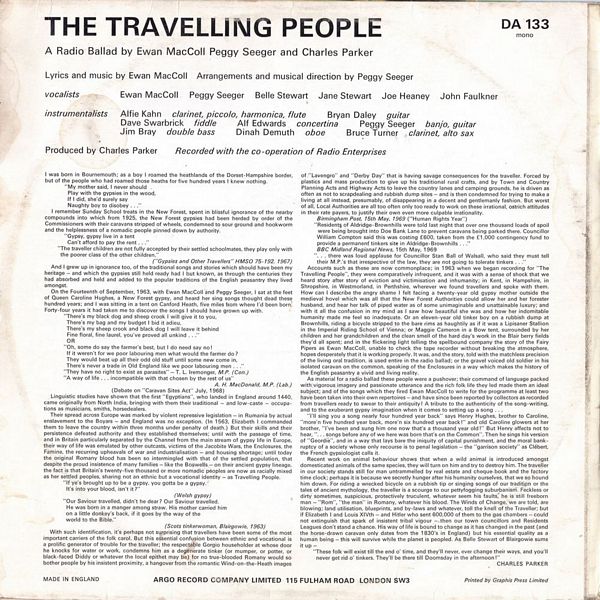

Sleeve Notes

I was born in Bournemouth; as a boy I roamed the heathlands of the Dorset-Hampshire border, but of the people who had roamed those heaths for five hundred years I knew nothing.

"My mother said, I never should

Play with the gypsies in the wood,

If I did, she'd surely say

Naughty boy to disobey …

I remember Sunday School treats in the New Forest, spent in blissful ignorance of the nearby compounds into which from 1925, the New Forest gypsies had been herded by order of the Commissioners with their caravans stripped of wheels, condemned to sour ground and hookworm and the helplessness of a nomadic people pinned down by authority.

"Gypsy, gypsy live in a tent

Can't afford to pay the rent …

"The traveller children are not fully accepted by their settled schoolmates, they play only with the poorer class of the other children."

("Gypsies and Other Travellers" HMSO 75-192. 1967)

And I grew up in ignorance too, of the traditional songs and stories which should have been my heritage — and which the gypsies still held ready had I but known, as through the centuries they had absorbed and held and added to the popular traditions of the English peasantry they lived amongst.

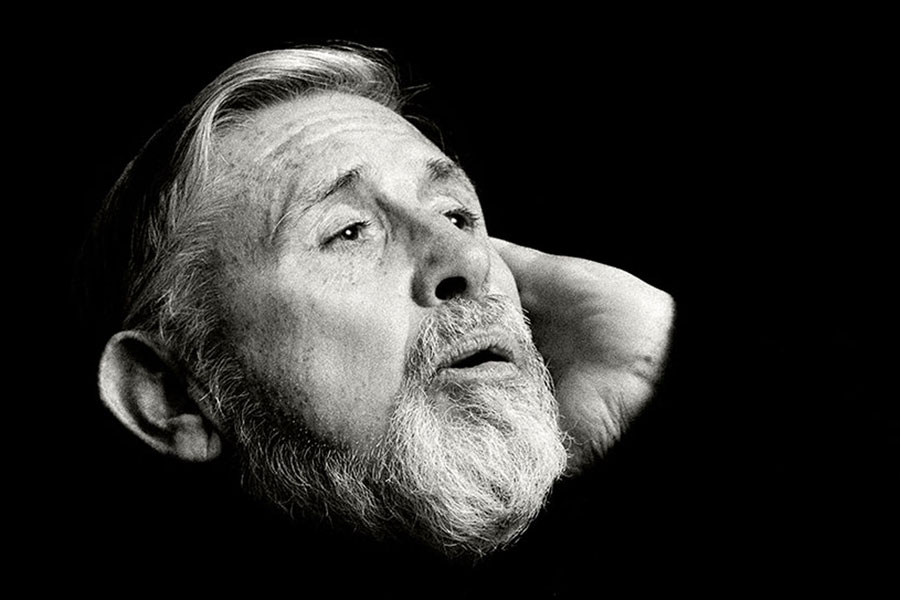

On the Fourteenth of September, 1963, with Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger, I sat at the feet of Queen Caroline Hughes, a New Forest gypsy, and heard her sing songs thought dead these hundred years; and I was sitting in a tent on Canford Heath, five miles from where I'd been born. Forty-four years it had taken me to discover the songs I should have grown up with.

"There's my black dog and sheep crook I will give it to you,

There's my bag and my budget I bid it adieu,

There's my sheep crook and black dog I will leave it behind

Fine floral, fine laurel, you've proved all unkind …

OR

"Oh, some do say the farmer's best, but I do need say no!

If it weren't for we poor labouring men what would the farmer do ?

They would beat up all their odd old stuff until some new come in,

There's never a trade in Old England like we poor labouring men …

"They have no right to exist as parasites" — T. L. Iremonger, M.P. (Con.)

"A way of life … incompatible with that chosen by the rest of us" —

A. H. MacDonald, M.P. (Lab.)

(Debate on "Caravan Sites Act" July, 1968)

Linguistic studies have shown that the first "Egyptians", who landed in England around 1440, came originally from North India, bringing with them their traditional — and low-caste — occupations as musicians, smiths, horsedealers.

Their spread across Europe was marked by violent repressive legislation — in Rumania by actual enslavement to the Boyars — and England was no exception. (In 1563, Elizabeth I commanded them to leave the country within three months under penalty of death.) But their skills and their persistence defeated authority and they established themselves; until with the passage of time, and in Britain particularly separated by the Channel from the main stream of gypsy life in Europe, their way of life was emulated by other outcasts, victims of the Jacobite Wars, the Enclosures, the Famine, the recurring upheavals of war and industrialisation — and housing shortage; until today the original Romany blood has been so intermingled with that of the settled population, that despite the proud insistence of many families — like the Boswells — on their ancient gypsy lineage, the fact is that Britain's twenty-five thousand or more nomadic peoples are now as racially mixed as her settled peoples, sharing not an ethnic but a vocational identity — as Travelling People.

"If ye's brought up to be a gypsy, you gotta be a gypsy.

It's into your blood, isn't it?"

(Welsh gypsy)

"Our Saviour travelled, didn't he dear? Our Saviour travelled.

He was born in a manger among straw. His mother carried him

on a little donkey's back, if it goes by the way of the

world to the Bible."

(Scots tinkerwoman, Blairgowie, 1963)

With such identification, it's perhaps not surprising that travellers have been some of the most important carriers of the folk carol. But this essential confusion between ethnic and vocational is a prolific generator of trouble for the traveller; the respectable Gorgio householder at whose door he knocks for water or work, condemns him as a degenerate tinker (or mumper, or potter, or black-faced Diddy or whatever the local epithet may be) for no true-blooded Romany would so bother people by his insistent proximity, a hangover from the romantic Wind-on-the-Heath images of "Lavengro" and "Derby Day" that is having savage consequences for the traveller. Forced by plastics and mass production to give up his traditional rural crafts, and by Town and Country Planning Acts and Highway Acts to leave the country lanes and camping grounds, he is driven as often as not to scrapdealing and rubbish dump sites — and is then condemned for trying to make a living at all instead, presumably, of disappearing in a decent and gentlemanly fashion. But worst of all, Local Authorities are all too often only too ready to work on these irrational, ostrich attitudes in their rate payers, to justify their own even more culpable irrationality.

Birmingham Post, 15th May, 1969 ("Human Rights Year")

"Residents of Aldridge-Brownhills were told last night that over one thousand loads of spoil were being brought into Doe Bank Lane to prevent caravans being parked there. Councillor William Compton said this was costing £600, taken from the £1,000 contingency fund to provide a permanent tinkers site in Aldridge-Brownhills … "

BBC Midland Regional News, 15th May, 1969

" … . there was loud applause for Councillor Stan Ball of Walsall, who said they must tell their M.P.'s that irrespective of the law, they are not going to tolerate tinkers … "

Accounts such as these are now commonplace; in 1963 when we began recording for "The Travelling People", they were comparatively infrequent, and it was with a sense of shock that we heard story after story of eviction and victimisation and inhumanity; in Kent, in Hampshire, in Shropshire, in Westmorland, in Perthshire, wherever we found travellers and spoke with them. How can I describe the angry shame I felt facing a twenty-year old gypsy mother outside the medieval hovel which was all that the New Forest Authorities could allow her and her forester husband, and hear her talk of piped water as of some unimaginable and unattainable luxury; and with it all the confusion in my mind as I saw how beautiful she was and how her indomitable humanity made me feel so inadequate. Or an eleven-year old tinker boy on a rubbish dump at Brownhills, riding a bicycle stripped to the bare rims as haughtily as if it was a Lipisaner Stallion in the Imperial Riding School of Vienna; or Maggie Cameron in a Bow tent, surrounded by her children and her grandchildren and the clean smell of the hard day's work in the Blair berry fields they'd all spent; and in the flickering light telling the spellbound company the story of the Fairy Pipers as Ewan MacColl, unable to check the tape recorder without breaking the atmosphere, hopes desperately that it is working properly. It was, and the story, told with the matchless precision of the living oral tradition, is used entire in the radio ballad; or the gravel voiced old soldier in his isolated caravan on the common, speaking of the Enclosures in a way which makes the history of the English peasantry a vivid and living reality.

As material for a radio ballad these people were a pushover; their command of language packed with vigorous imagery and passionate utterance and the rich folk life they led made them an ideal subject; and of the songs which they fired Ewan MacColl to write for the programme at least two have been taken into their own repertoires — and have since been reported by collectors as recorded from travellers ready to swear to their antiquity! A tribute to the authenticity of the song-writing, and to the exuberant gypsy imagination when it comes to setting up a song …

"I'll sing you a song nearly four hundred year back" says Henry Hughes, brother to Caroline, "more'n five hundred year back, more'n six hundred year back!" and old Caroline glowers at her brother, "I've been and sung him one now that's a thousand year old!" But Henry affects not to hear, " … songs before any of we here was born that's on the Common". Then he sings his version of "Geordie", and in a way that lays bare the iniquity of capital punishment, and the moral bankruptcy of a society whose only recourse is to penal legislation — the "garrison society" as Clébert, the French gypsiologist calls it.

Recent work on animal behaviour shows that when a wild animal is introduced amongst domesticated animals of the same species, they will turn on him and try to destroy him. The traveller in our society stands still for man untrammelled by real estate and cheque book and the factory time clock; perhaps it is because we secretly hunger after his humanity ourselves, that we so hound him down. For riding a wrecked bicycle on a rubbish tip or singing songs of our tradition or the tales of ancient mythology, the traveller is a scourge to our pettyfogging suburbanism. Feckless or dirty sometimes, suspicious, protectively truculent, whatever seem his faults, he is still freeborn man — "Rom", "the man" in Romany, whatever his blood. The Winds of Change, we are told, are blowing; land utilisation, blueprints, and by-laws and whatever, toll the knell of the Traveller; but if Elizabeth I and Louis XIVth — and Hitler who sent 600,000 of them to the gas chambers — could not extinguish that spark of insistent tribal vigour — then our town councillors and Residents Leagues don't stand a chance, His way of life is bound to change as it has changed in the past (and the horse-drawn caravan only dates from the 1830's in England) but his essential quality as a human being — this will survive while the planet is peopled. As Belle Stewart of Blairgowie sums it up —

"These folk will exist till the end o' time, and they'll never, ever change their ways, and you'll never get rid o' tinkers. They'll be there till Doomsday in the afternoon!"

CHARLES PARKER