|

|

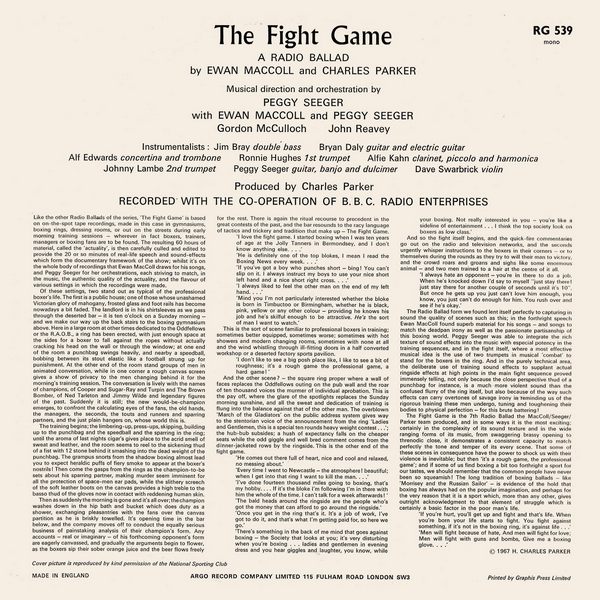

* Bob Davenport is credited as a singer on the CD but not the original vinyl release of The Fight Game …

"I was due to do Song of the Road but I went into hospital with tuberculosis so Louis Killen replaced me. I did The Fight Game. That was 1963. I went to America, came back and was told, 'Oh, you got it all wrong … all your songs were out of key.' I was singing with guys who read notes and I was singing around the theme. I'd listened to enough jazz to sing around a theme but they said, 'Oh, we took that out and took this out.'

Then they said they want to put it out on Argo on an LP and they wanted clearance. I said, 'Yeah, you can have clearance but my name must not appear anywhere — publicity, the cover, not anywhere at all.' They agreed to that but unfortunately Tony Engle, when they put it out on CD, hadn't read that contract, so my name's on it.

When the guy who wrote the book about the Radio Ballads asked Peggy Seeger, 'Why didn't you use Bob Davenport more?', she said she didn't know. I think the simple reason was they didn't like my voice. Charles Parker said to me, 'We've got you in The Fight Game, Davenport, but you're a music hall singah.'"

Bob Davenport — from: Singing from the Floor: A History of British Folk Clubs

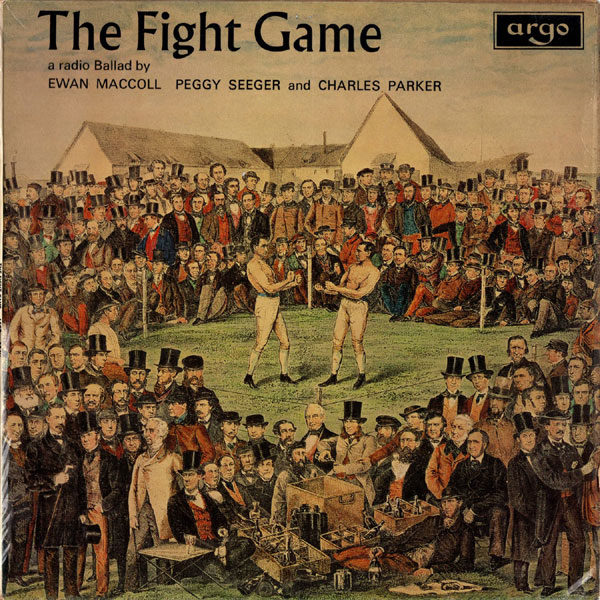

Sleeve Notes

Like the other Radio Ballads of the series, The Fight Game' is based on on-the-spot tape recordings, made in this case in gymnasiums, boxing rings, dressing rooms, or out on the streets during early morning training sessions — wherever in fact boxers, trainers, managers or boxing fans are to be found. The resulting 60 hours of material, called the 'actuality', is then carefully culled and edited to provide the 20 or so minutes of real-life speech and sound-effects which form the documentary framework of the show; whilst it's on the whole body of recordings that Ewan MacColl draws for his songs, and Peggy Seeger for her orchestrations, each striving to match, in the music, the authentic quality of the actuality, and the flavour of various settings in which the recordings were made.

Of these settings, two stand out as typical of the professional boxer's life. The first is a public house; one of those whose unashamed Victorian glory of mahogany, frosted glass and foot rails has become nowadays a bit faded. The landlord is in his shirtsleeves as we pass through the deserted bar — it is ten o'clock on a Sunday morning -and we make our way up the back stairs to the boxing gymnasium above. Here in a large room at other times dedicated to the Oddfellows or the R.A.O.B., a ring has been erected, with just enough space at the sides for a boxer to fall against the ropes without actually cracking his head on the wall or through the window; at one end of the room a punchbag swings heavily, and nearby a speedball, bobbing between its stout elastic like a football strung up for punishment. At the other end of the room stand groups of men in animated conversation, while in one corner a rough canvas screen gives a show of privacy to the men changing behind it for the morning's training session. The conversation is lively with the names of champions, of Cooper and Sugar-Ray and Turpin and The Brown Bomber, of Ned Tarleton and Jimmy Wilde and legendary figures of the past. Suddenly it is still; the new would-be-champion emerges, to confront the calculating eyes of the fans, the old hands, the managers, the seconds, the touts and runners and sparring partners, and the just plain hangers on, whose world this is.

The training begins; the limbering-up, press-ups, skipping, building up to the punchbag and the speedball and the sparring in the ring; until the aroma of last nights cigar's gives place to the acrid smell of sweat and leather, and the room seems to reel to the sickening thud of a fist with 12 stone behind it smashing into the dead weight of the punchbag. The grampus snorts from the shadow boxing almost lead you to expect heraldic puffs of fiery smoke to appear at the boxer's nostrils I Then come the gasps from the rings as the champion-to-be sets about his sparring partner, making murder seem imminent for all the protection of space-men ear pads, while the slithery screech of the soft leather boots on the canvas provides a high treble to the basso thud of the gloves now in contact with reddening human skin.

Then as suddenly the morning is gone and it's all over; the champion washes down in the hip bath and bucket which does duty as a shower, exchanging pleasantries with the fans over the canvas partition as he is briskly towelled. It's opening time in the bar below, and the company moves off to conduct the equally serious business of painstaking analysis of their champion's form. Any accounts — real or imaginary — of his forthcoming opponent's form are eagerly canvassed, and gradually the arguments begin to flower, as the boxers sip their sober orange juice and the beer flows freely for the rest. There is again the ritual recourse to precedent in the great contests of the past, and the bar resounds to the racy language of tactics and trickery and tradition that make up — The Fight Game. 'I love the fight game. I started boxing when I was ten years of age at the Jolly Tanners in Bermondsey, and I don't know anything else … '

'He is definitely one of the top blokes, I mean I read the Boxing News every week … '

'If you've got a boy who punches short — bing! You can't slip on it. I always instruct my boys to use your nice short left hand and a nice short right cross … '

'I always liked to feel the other man on the end of my left hand.

'Mind you I'm not particularly interested whether the bloke is born in Timbuctoo or Birmingham, whether he is black, pink, yellow or any other colour — providing he knows his job and he's skilful enough to be attractive. He's the sort of man I want to watch.'

This is the sort of scene familiar to professional boxers in training; sometimes better equipped, sometimes worse; sometimes with hot showers and modern changing rooms, sometimes with none at all and the wind whistling through ill-fitting doors in a half converted workshop or a deserted factory sports pavilion.

'I don't like to see a big posh place like, I like to see a bit of roughness; it's a rough game the professional game, a hard game!'

And the other scene? — the square ring proper where a wall of faces replaces the Oddfellows outing on the pub wall and the roar of ten thousand voices the murmer of individual approbation. This is the pay off, where the glare of the spotlights replaces the Sunday morning sunshine, and all the sweat and dedication of training is flung into the balance against that of the other man. The overblown 'March of the Gladiators' on the public address system gives way to the stentorian voice of the announcement from the ring 'Ladies and Gentlemen, this is a special ten rounds heavy weight contest … '; the hub-bub subsides; a hush of expectancy falls on the cheaper seats while the odd giggle and well bred comment comes from the dinner-jacketed rows by the ringside. This is the other end of the fight game.

'He comes out there full of heart, nice and cool and relaxed, no messing about.'

'Every time I went to Newcastle — the atmosphere! beautiful; when I get into that ring I want to kill the man … '

'I've done fourteen thousand miles going to boxing, that's my hobby … . If it's the bloke I'm following I'm in there with him the whole of the time. I can't talk for a week afterwards!' 'The bald heads around the ringside are the people who's got the money that can afford to go around the ringside.' 'Once you get in the ring that's it. It's a job of work, I've got to do it, and that's what I'm getting paid for, so here we go.'

'There's something in the back of me mind that goes against boxing — the Society that looks at you; it's very disturbing when you're boxing … ladies and gentlemen in evening dress and you hear giggles and laughter, you know, while your boxing. Not really interested in you — you're like a sideline Of entertainment … I think the top society look on boxers as low class.'

And so the fight itself begins, and the quick-fire commentaries go out on the radio and television networks, and the seconds urgently whisper instructions to the boxers in their corners — or to themselves during the rounds as they try to will their man to victory, and the crowd roars and groans and sighs like some enormous animal — and two men trained to a hair at the centre of it all.

'I always hate an opponent — you're in there to do a job. When he's knocked down I'd say to myself "just stay there I just stay there for another couple of seconds until it's 10". But once he gets up you just can't love him enough, you know, you just can't do enough for him. You rush over and see if he's okay.'

The Radio Ballad form we found lent itself perfectly to capturing in sound the quality of scenes such as this; in the forthright speech Ewan MacColl found superb material for his songs — and songs to match the deadpan irony as well as the passionate partisanship of this boxing world. Peggy Seeger was able to integrate the rich texture of sound effects into the music with especial potency in the training sequences, and in the fight itself, where a most effective musical idea is the use of two trumpets in musical 'combat' to stand for the boxers in the ring. And in the purely technical area, the deliberate use of training sound effects to supplant actual ringside effects at high points in the main fight sequence proved immensely telling, not only because the close perspective thud of a punchbag for instance, is a much more violent sound than the confused flurry of the ring itself, but also because of the way such effects can carry overtones of savage irony in reminding us of the rigorous training these men undergo, tuning and toughening their bodies to physical perfection — for this brute battering I

The Fight Game is the 7th Radio Ballad the MacColl/Seeger/ Parker team produced, and in some ways it is the most exciting; certainly in the complexity of its sound texture and in the wide ranging forms of its music, from swaggering brassy opening to threnodic close, it demonstrates a consistent capacity to match perfectly the tone and temper of its every scene. That some of these scenes in consequence have the power to shock us with their violence is inevitable; but then 'it's a rough game, the professional game'; and if some of us find boxing a bit too forthright a sport for our tastes, we should remember that the common people have never been so squeamish! The long tradition of boxing ballads — like 'Morrisey and the Russian Sailor' — is evidence of the hold that boxing has always had on the popular imagination, and perhaps for the very reason that it is a sport which, more than any other, gives outright acknowledgment to that element of struggle which is certainly a basic factor in the poor man's life.

'If you're hurt, you'll get up and fight and that's life. When you're born your life starts to fight. You fight against something, if it's not in the boxing ring, it's against life … ' 'Men will fight because of hate, And men will fight for love; Men will fight with guns and bombs, Give me a boxing glove …

H. Charles Parker

© 1967