|

|

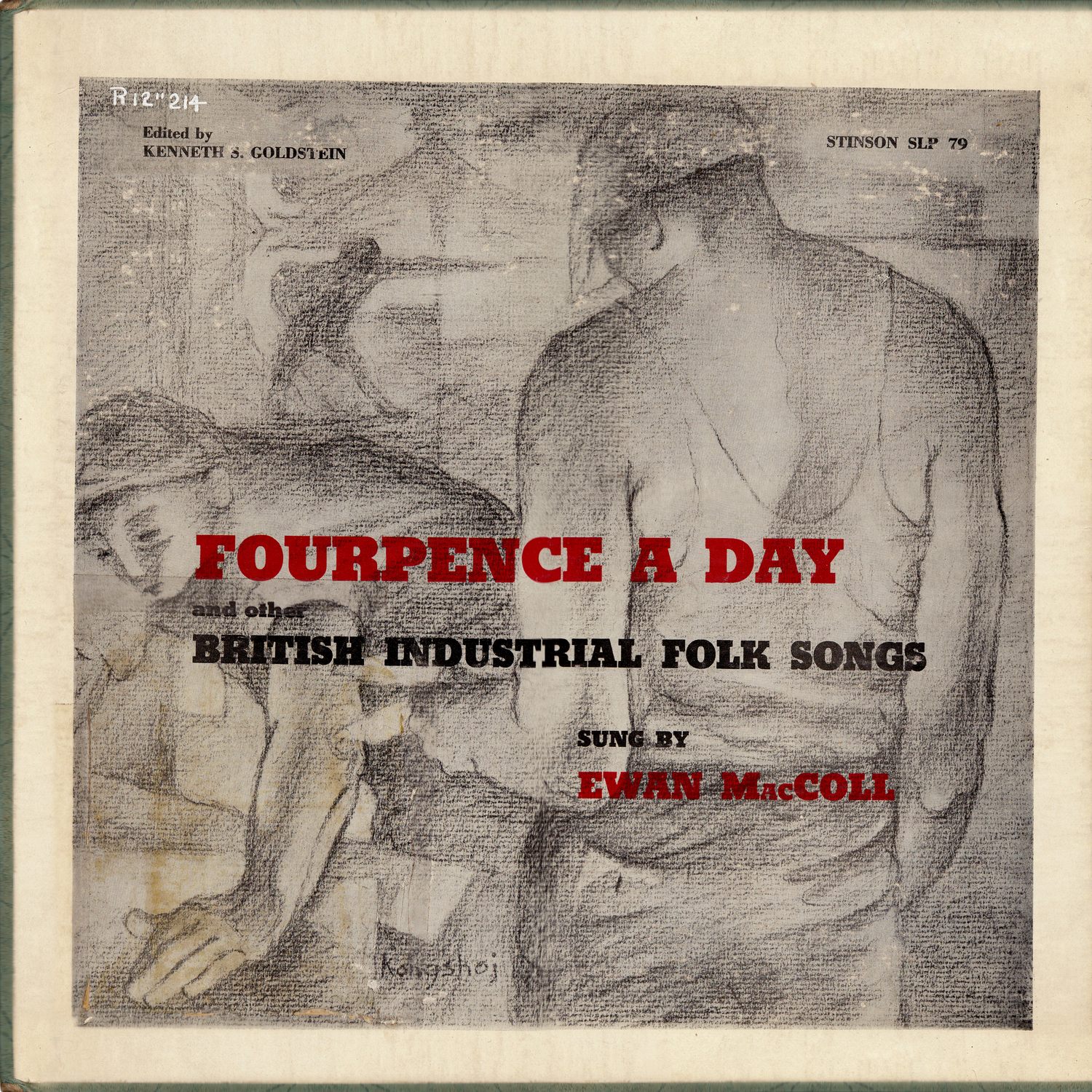

Sleeve Notes

The songs in this album were made by colliers, weavers and spinners, by bards with dirty faces and segs on their hands, by minstrels in denim overalls and dungarees. Many of them are rough songs made to old tunes; the words are gritty with cold dust and sweat. Some of them are makeshift jobs and others have had the rough edges smoothed away with constant usage. Some are as crude as an old spade and some are as neat as precision tools. They were made yesterday, a hundred years ago. They've been sung a mile under the earth in the roads where the sun never shines and they've risen above the clatter of handlooms.

They represent the pride, the creativeness and the capacity for living of that indispensable part of the community, the men who dig coal, the men and women who spin and weave textiles and the drivers, shovel-slingers, porters, hammer-balancers, fat lads, steam raisers, fire-droppers and everybody connected with the iron road. Such people have a very proper sense of values; courage is a fine thing, so they sing about it. Love is a fine thing, so they sing about it, and pride in one's class is a fine thing, so they sing about that too.

There are terrors and hardships in the life of a miner but that is not the whole story; there is hunger and poverty in the life of a weaver but that is not the whole story either. The miner is more than a mere instrument for digging coal and the weaver is more than a cloth fashioning machine; they are men with all the dreams and aspirations of the race. So they lift up their voices and ask the world "If it wasn't for the weavers, what would you do?". And their womenfolk sing sweet and tender ballads like The Collier Laddie. And if Romeo works at the loom or handles a pick at the coalface, then he is no less desirable in Juliet's eyes for that. And she sings no less sweetly because she lives in a cottage facing a slap-heap and nurses her baby in between doing the week's wash and preparing the evening meal.

— EWAN MacCOLL

POOR PADDY WORKS ON THE RAILWAY

This song, long popular in the United States, was the product of Irish immigrant laborers who moved west with the great railway expansions in the middle of the 19th century. For the most part, the British railways, too, were laid by Irish laborers. The song may well have 'found its way to Britain by means of merchant seamen who used the song as a capstan shanty. The form in which it was used at sea was undoubtedly taken over wholly from stage comedians and music hall performers in whose repertoire it was a favorite. A recent questionnaire circulated in a number of locomotive sheds in northern England, produced five versions of this song. In the past two years, British folksingers have tended to fuse two versions into a single song. MacColl sings a collation of a slow version from Liverpool and a fast version from Hellefield in Yorkshire.

THE GRESFORD DISASTER

The mining disaster described in this ballad occurred on September 22, 1934. The ballad, properly bitter in its editorialized narrative, slightly underestimates the casualties—265 miners were killed, including three rescue men. MacColl learned the song from a young miner named Ford in Sheffield Miners' Training Centre. The five mining songs in this album may be found, in one variant or another, in A. L. Lloyd's Come All Ye Bold Miners, a collection of British ballads and songs of the coalfields, published by Lawrence & Wishart Ltd., London, 1952.

THE FOUR LOOM WEAVER

One of the most dramatic of British industrial folk songs, this ballad was first sung shortly after the Battle of Waterloo, when handloom weavers' wages fell to a new low. It was apparently a favorite song for many years, as evidenced by the great number of broadsheet prints issued under this and other titles. Controversy as to its authorship exists. One popular theory is that it was the work of John of Greenfield Junior, himself the character in a popular 19th century comic ballad. The version recorded by MacColl was communicated to him by Becket Whitehead of Delph, near Oldham, Lancashire.

I'M CHAMPION AT KEEPING 'EM ROLLING

This song was written by Ewan MacColl in 1949 for a radio program about one of the great truck roads running from London to Scotland. It has since become the anthem of British truck drivers who have added countless new-verses, few of which would pass censor. The words were set to the tune of the popular 18th century Irish song The Limerick Rake.

THE COLLIER LADDIE

One of the oldest and most beautiful of Britain's industrial ballads, this song dates back to at least the 17tth Century. Robert Burns noted it and sent it to James Johnson, editor of The Scots Musical Museum, with the comment, "I do not know a blyther old song then this." The song reflects the spirit of pride and independence which characterizes the men of the mining communities. The song, still fairly widely known, is most commonly found among farm workers who sometimes substitute 'ploughman laddie' for 'collier laddie'. MacColl's version is from the singing of Isabell Henry of Auchterarder, Perthshire.

THE COAL OWNER AND THE PITMAN'S WIFE

This ballad is believed to date from the Durham strike of 1844 and to have been written by William Hornsby, a collier of Shotton Moor, Durham. The ballad was discovered among a collection of papers relating to the strike by a studious Lancashire miner, J. S. Bell. The tune was supplied by J. Denison, of Walker, and together with the text, can be found in Lloyd's Come All Ye Bold Miners.

THE IRON HORSE

According to A. L. Lloyd, this song was written by Charles Balfour, stationmaster at Glencarse, Scotland, and was first performed at a railwayman's festival in 1848. It remained popular in the neighborhood of Perth and Dundee for many years and was a favorite in the ploughmen's bothies (cottages) of Aberdeenshire. There are few folk who remember it now. The tune is an adaption of The Piper of Dundee. MacColl's version comes from the Dundee Loco Shed and is collated with the version found in Robert Fordis Vagabond Songs and Ballads of Scotland.

THE BLANTYRE EXPLOSION

The disaster described in this ballad occurred at Messrs Dixon's colliery, High Blantyre, near

Glasgow, on October 22, 1877, with the resulting death of over 200 miners. Unlike many pit-disaster ballads which take the form of the Irish 'come all ye' songs, The Blantyre Explosion is in the tradition of the South-West Scottish elegy. The melody was widely used in the United States, and the most famous song associated with it is The Cumberland's Crew, a heart-rending description of a Naval battle in the war between the states. The version of The Blantyre Explosion sung here was collected in 1951 and first appeared in A. L. Lloyd's Come All Ye Bold Miners.

THE WARK OF THE WEAVERS

The handloom weaver, while carrying his finished products to the nearest center of commerce, became familiar with the countryside (and with the women in whose kitchens he settled temporarily to weave thread.) The distances to be covered were often considerable and (except for the above mentioned diversion) the only relief from the rigors of the road was to be found in the weavers' howffs (poor inns). Over a glass of 'tuppeny' a man could exchange gossip, talk politics, boast of his conquests, and roar out his defiance of a world seemingly bent on starving him. Even after the old travelling weavers had been absorbed into the mills, their songs retained much of the old pride and defiance. This song belongs to the period of nearly 200 years ago, when weaving was just changing from a handicraft to an industry. Originally from Kincardinshire in southern Scotland, it is now widely sung throughout the southern and eastern regions.

FOURPENCE A DAY

This song is over a hundred years old. Still current in parts of northeast Yorkshire, it is attributed to Thomas Raine, lead-miner and bard of Teesdale. The lead mines in this area have been worked since Roman times. The operators worked these small mines on skinflint principles. The washing rakes, where the lead-bearing rocks were separated from the clay and gravel, were usually operated by young boys or old disabled miners. The mine owners were supposed to have become so incensed by the song that they closed the pits and imported leadminers from Germany. The song was collected by Joan Littlewood and Ewan MacColl from John Gowland, retired lead-miner of Middleton-in-Teesdale.

COSHER BAILEY'S ENGINE

The real life hero of this song was a Monmouth ironmaster who built the Taff Vale Railway along the Aberdare Valley in 1846. According to legend, he drove the first train along the railway himself and got stuck in a tunnel, an event immortalized in several verses of the song. It has dozens of verses, many quite rough, some completely unsuitable for respectable company. It is sung to the tune of the traditional Welsh song The Black Pig. A. L. Lloyd informs us that the motif of the Devil allowing a master to set up a Hell of his own (usually a foundry or mine) is a familiar one in industrial folklore. The version sung by Mr. MacColl was collected by Alan Lomax from the singing of John H. Davies of Treorchy, South Wales.

Notes by KENNETH S. GOLDSTEIN

(Prepared with the kind assistance of A. L. Lloyd and Ewan MacColl)

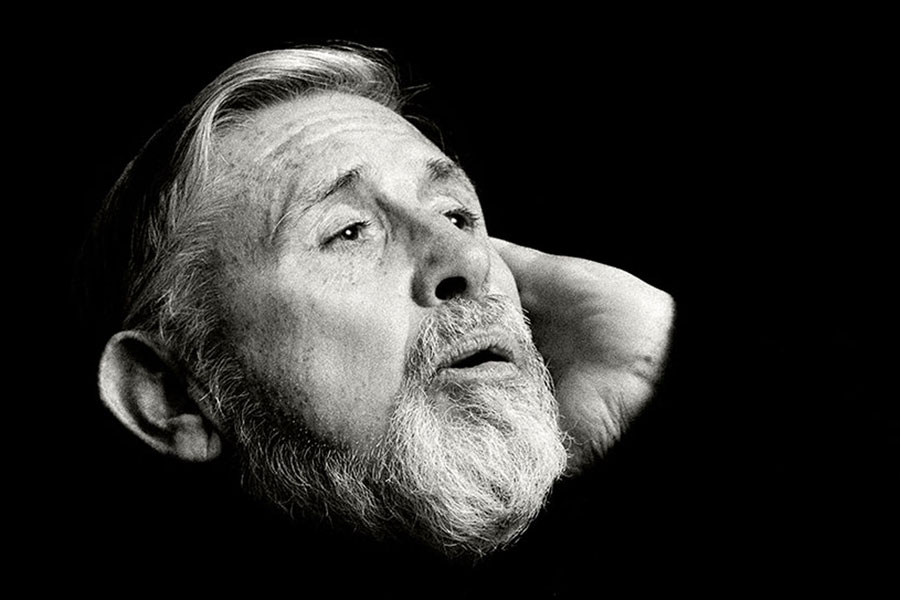

ABOUT THE SINGER

EWAN MacCOLL is the Scots-born son of a Gaelic-speaking mother and Lowland father from whom he inherited more than a hundred songs. His father, an iron-moulder and militant trade unionist, was so frequently black-listed that the family was forced to be constantly on the move. MacColl has worked as a laborer for the English subsidiary of Anaconda Copper, as well as a garage hand, builders laborer, organizer of the unemployed, journalist on a Textile journal, radio scriptwriter, actor and dramatist.

Since the war, MacColl has written and broadcast extensively about folk music. He was general editor of the British Broadcasting Corporation folk music series, "Ballads and Blues", and frequently took part in Alan Lomax's radio and television shows for B.B.C. His folksong publications include PERSONAL CHOICE, a pocket edition of Scottish folksongs and ballads, and THE SHUTTLE AND THE CAGE, the first published collection of British industrial folk songs. Both of these collections are available from Hargail Music Press, 130 West 56th Street, New York City.