|

|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

INTRODUCTION

PERHAPS NO DATE in the recent history of published Burnsiana is more important than that on which the Auk Society edition of THE MERRY MUSES OF CALEDONIA came off the presses of M. MacDonald of Edinburgh in 1959. Not only was this an openly published edition, not intended for under-the-counter sales by irresponsible vendors of pornography; not only was this the first modern edition of The Merry Muses which minced no words (or spelling either, with common Anglo-Saxon four letter monosyllabic words properly used both in verse and editorial text); but it was the first edition to be responsibly edited by leading Burns scholars who, wielding neither the poet's pen nor seeing any necessity for protecting or defending the good name of the Ayrshire bard, have reproduced exactly every word and letter of the bawdy verse with which he is associated through the pages of the best known and most frequently published collection of song-erotica in the English-speaking world.

Indeed, the producers of this unique recording of unexpurgated songs from The Merry Muses (which was inspired by the Auk Society edition of this important collection) recommend that every purchaser of this album first read through the volume discussed here. From J. DeLancey Ferguson's important essay on "Sources and Texts of the Suppressed Poems," through the late James Barke's socio-psychologically oriented statement on "Pornography and Bawdry in Literature and Society," to Sidney Goodsir Smith's introductory note on "Burns and the Merry Muses," the opening pages of this volume are in themselves worth the price of the book. But the main course in this fabulous repast are the texts for the slightly less than 100 pieces which appear as reprinted from holograph manuscripts, the original circa 1800 edition, and later sources of songs either composed, collected or revamped by Burns. To Burns scholars, amateur or professional, to folklorists, sociologists, literary historians, anthropologists, and to that special breed of modern man sometimes referred to as 'erotica specialists', this work is a prime source of both erudite information … and pleasure.

Whether one agrees with the various conclusions arrived at by Messrs. Ferguson, Barke and Smith, or chooses to disagree with them on one point or another (as does the editor of this recording), the volume is certainly a source of intelligently organized and recondite commentary on The Merry Muses, Burns, and his interest in folk bawdry. But one must not be lulled into that realm of self delusion which permits most members of our society to deny their own interest in erotica — except (they will tell us) as material for objective, scientific pursuit of knowledge. The man who does not enjoy these songs for themselves, totally removed from their value in supplying him with materials for further study, is a dead man.

In line with this, the editor of this album has chosen to write a set of headnotes to each of the 24 songs included in this recording which will supply interested parties with a summary of the best available information drawn from the standard sources. This will permit listeners to enjoy the songs for their own sakes without supplying them with built-in excuses for listening to the songs for the alleged purpose of pursuing knowledge to its logical end — the logical end (pedants would have us believe) being knowledge for the sake of knowledge. Burns himself derived great pleasure in collecting, singing and writing these pieces — we invite you to join him in his pleasure. At times the editor has taken it into his head to supply some of his own opinions about certain problems relative to the sources of these songs. They are meant only to suggest alternate approaches to sometimes difficult or baffling problems. Store them away for future reference — never let them interfere with or detract from your first or later pleasureful listenings to this recording.

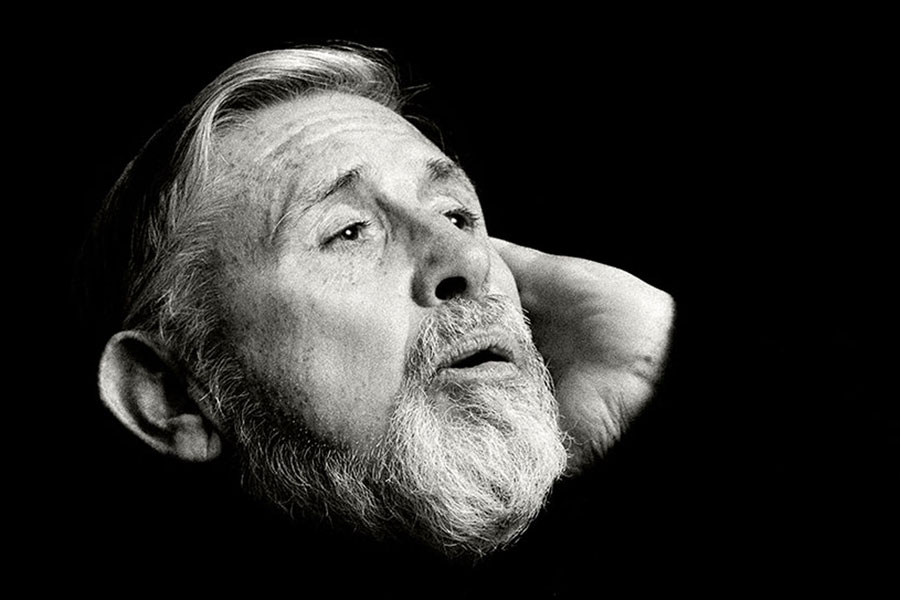

The production of this recording presented many problems, immediate and potential. The Auk Society edition of The Merry Muses contained little information about the music of the songs other than to supply the titles of the tunes to which they were sung, when such information was known. The present record is intended to be a musical supplement to that volume. The songs may read well or poorly as folk or art poetry but, almost without exception, they sing superbly, and certainly far better than they read. But in their performance they may be (and have been) so badly butchered that listening to them is like "hearing the cadaverous ecstasy of offal" (as Hugh MacDiarmid, Scotland's greatest living poet, has written in another context). The selection of a singer for this recording was not a difficult one, however. Indeed, there was no question of finding the proper person for the task. There was only one singer who could perform these songs with that knowledge, sympathy, empathy, verility and vocal ability which the songs demanded. That singer was EWAN MacCOLL, many of whose previous recordings had been produced and edited by the editor of the present recording. And the project proved to be one which MacColl himself had independently decided to do at some time, and which production he joined with fervor. The selection of the songs was the next problem to be faced. To 'play it safe' and avoid potential prosecution, the producers could well have selected those songs containing no so-called 'obscene' words and whose euphemistic and polite references to matters of sex would prove inoffensive to the ever pervasive censors (for this is surely an age of censors). To do so, however, would have been to defeat the very purpose for which the present recording was first conceived. It was therefor resolved that the singer was to make his own selection of songs and that such selection was to be both representative of the entire collection and at the same time the best of the available material. Here, too, MacColl's intentions coincided with those of the producers. The songs were performed unaccompanied, certainly as they might have been sung by the Scots folk themselves.

After the songs had been selected and recorded, the producers found themselves questioning their intelligence in the matter. Legal advice concerning the issuance of such a recording was sought. Some lawyers advised wholely against it, others suggested its being utilized as a test case. Friendly scholars and other interested and experienced people gave us their opinions. Some suggested expurgating the recording by omitting those songs containing certain potentially objectionable verbs and nouns. In the final analysis we decided to issue the recording as it was originally conceived — unexpurgated and representative of the whole collection. The materials are in no way compromised. The compromise which the producers have made was to issue the recordings in such a manner as to make them generally unavailable to the man in the street. The edition is strictly limited to 500 copies. The price of the set was raised to a point at which it became prohibitively priced for a general market. And finally, the set has been made available by subscription only to a selected group of 'adult, mature and responsible' individuals — scholars and students in the fields of literature, folklore and related disciplines. It is a compromise which we would have preferred not having to make; the single restriction on the album should have been its sale to adults only. It is a shame that only 'responsible' selected scholars will be permitted to utilize this set for their various ends. May the scales show an equal balance of knowledge and pleasure.

The texts sung here do not always exactly follow the published texts, but vary only as to the use of unimportant prepositions and articles, dialect pronounciation, some refrain materials, and tune variation. In learning the songs, the singer made them his own and here presents them as part of a wholely digested musical and textual experience. The variation that exists is that which would be true for any natural folksinging experience. There is, however, no expurgation of text in such variation. The listener should refer to the Auk Society edition of The Merry Muses for the exact text originals.

The editor wishes to thank those individuals who have been of assistance with this production. They are too numerous to mention here, but they will know that lack of mention of their names is not a sign of discourtesy or lack of appreciation. Special thanks, however, must be singled out for Hamish Henderson, Research Fellow of the School of Scottish Studies and Scotland's leading folk song collector, and for Gershon Legman, of Valbonne, France, the leading scholar in the field of erotic folklore and an ever-vigilant, if sometimes impatient, critic of all that goes on in his chosen area of study.

Kenneth S. Goldstein

January, 1962.

A NOTE FROM THE SINGER

In selecting the songs included on this recording, I have chosen what I consider to be the cream of the material. There are other songs equally good in the collection, but there are few, if any, which are better. I have selected them with no desire to shock, but rather because I consider them good, some of them beautiful, songs.

Burns' collection of bawdry is not to everyone's taste. While there is in the collection a good deal that is witty and good naturedly bawdy, and while a surprising number of the songs succeed in being lusty and tender at the same time, there are also a number of items which are neither witty, good natured, or decently lustful. These latter are the kind of songs which are calculated to evoke from the listener the sly snigger, not the belly-laugh.

Love, the feeling and the act, is not a subject for the smart titter or the snigger behind the hand. It is an important phenomenon and needs an honest approach. It can be laughed at, yes, but not in falsetto. It needs to be approached with warmth and understanding. For the most part, Burns did just that with The Merry Muses. May I do the same?

Ewan MacColl

REFERENCE SOURCES

Aldine — George A. Aitken, editor, POETICAL WORKS OF ROBERT BURNS Aldine Edition, London, 1839.

Cook — Davidson Cook, "ANNOTATIONS OF SCOTTISH SONGS BY BURNS: AN ESSENTIAL SUPPLEMENT TO CROMEK AND DICK", article in the Burns Chronicle & Club Directory, No. XXXI, January, 1922 Burns Federation, Kilmarnock, pp. 1-21.

Herd — David Herd, THE ANCIENT AND MODERN SCOTS SONGS, HEROIC BALLADS Etc., Edinburgh, 1769 and 1776.

Letters Centenary — J. DeLancey Ferguson, THE LETTERS OF ROBERT BURNS, Oxford, 1931. W. E. Henley and T. F. Henderson, THE POETRY OF ROBERT BURNS, Centenary Edition, Edinburgh, 1896.

Hecht — Hans Hecht, SONGS FROM DAVID HERD'S MANUSCRIPTS, Edinburgh, 1904.

Dick, Notes — James C. Dick, NOTES ON SCOTTISH SONG BY ROBERT BURNS, WRITTEN IN AN INTERLEAVED COPY OF THE SCOTS MUSICAL MUSEUM, London, 1908.

Dick, Songs — James C. Dick, THE SONGS OF ROBERT BURNS, NOW FIRST PRINTED WITH THE MELODIES FOR WHICH THEY WERE WRITTEN, London, 1903.

Glen — John Glen, EARLY SCOTTISH MELODIES, Edinburgh, 1900.

Keith — Alexander Keith, BURNS AND FOLK-SONG, Aberdeen, 1922.

Illustrations — William Stenhouse, ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE LYRIC POETRY AND MUSIC OP SCOTLAND, Edinburgh, 1853 [This is the fourth volume of the 1853 edition of James Johnson's THE SCOTS MUSICAL MUSEUM].

MMC 1800 — MERRY MUSES OF CALEDONIA; A COLLECTION OF FAVOURITE SCOTS SONGS, ANCIENT AND MODERN; SELECTED FOR USE OF THE CROCHALLAN FENCIBLES, No place, no date, [circa 1800]. [The editor has not seen this volume, and references to it are from MMC '59.]

MMC 1827 — THE MERRY MUSES, A CHOICE COLLECTION OF FAVOURITE SONGS FROM MANY SOURCES BY ROBERT BURNS, No place, [predated] 1827. [The editor has not seen this volume, and references to it are from MMC '59.]

MMC '11 — THE MERRY MUSES OF CALEDONIA … A VINDICATION OF ROBERT BURNS IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE PUBLICATION AND THE SPURIOUS EDITIONS WHICH SUCCEEDED IT, Printed and published under the auspices of the Burns Federation, 1911 [Edited by Duncan M'Naught].

MMC '59 — THE MERRY MUSES OF CALEDONIA, edited by James Barke and Sidney Goodsir Smith, with a prefatory note and some authentic Burns texts contributed by J. DeLancey Ferguson, Edinburgh, 1959.

Sharpe — Charles K. Sharpe, A BALLAD BOOK, n.p., 1823 [The edition referred to in headnotes was edited by David Laing, and reprinted with additional notes and ballads from the manuscripts of C. K. Sharpe and Sir Walter Scott, Edinburgh, 1880].

SMM — James Johnson, publisher, THE SCOTS MUSICAL MUSEUM, CONSISTING OF SIX HUNDRED SCOTS SONGS, Edinburgh, 1787-1803 [The edition referred to in headnotes was edited by David Laing and William Stenhouse, and reprinted in four volumes, Edinburgh, 1853. Songs are referred to by the number assigned to them in the collection, which remained constant in all editions]

TTM — Allan Ramsay, THE TEA-TABLE MISCELLANY, Edinburgh, 1724, and numerous later editions. [The edition referred to in headnotes was reprinted in two volumes from the fourteenth edition, in Glasgow, 1876].

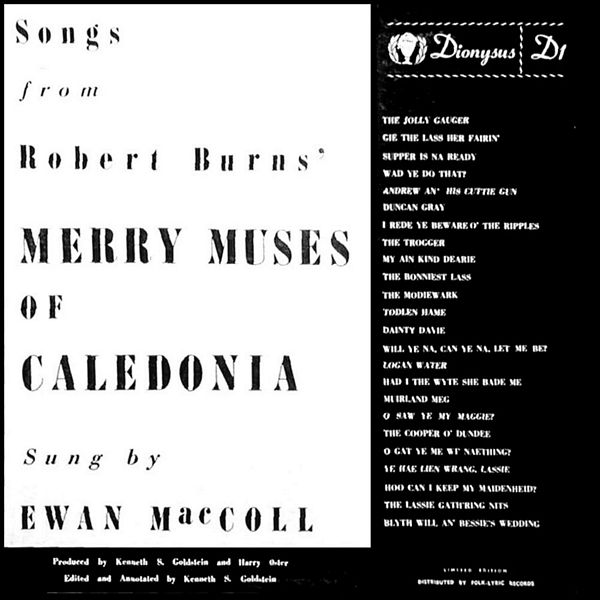

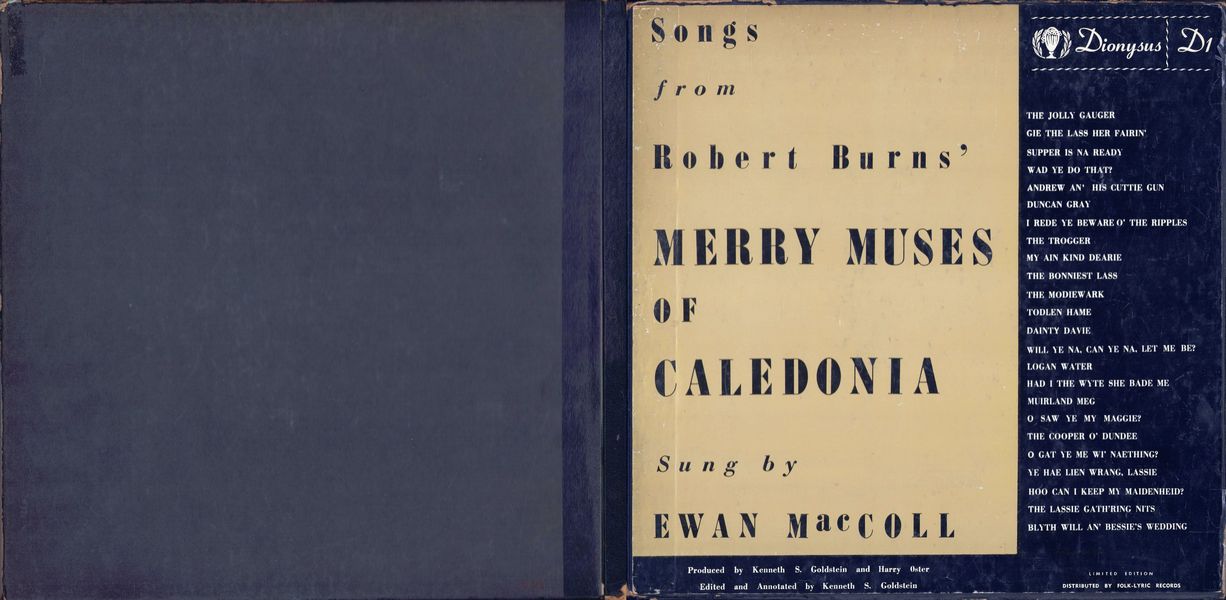

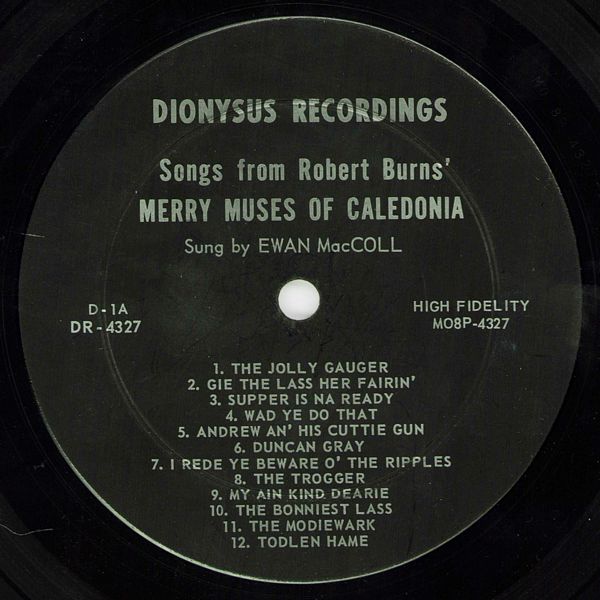

Songs from Robert Burns' THE MERRY MUSES OP CALEDONIA

Sung by EWAN MacCOLL

Edited and Annotated by KENNETH S. GOLDSTEIN

The Jolly Gauger — This piece is most certainly a parody of "The Jolly Beggar" (Child #279), authorship of which is traditionally attributed to James V of Scotland. A single verse of the original will clearly show its relationship to "The Jolly Gauger":

"There was a jolly beggar, and a begging he was bound,

And he took up his quarters into a land'art town,

And we'll gang nae mair a roving sae late into the night,

And we'll gang nae mair a roving, boys, let the moon shine ne'er sae bright,

And we'll gang nae mair a roving."

— Herd (1776), Volume II, pp. 26-28,

Scott Douglas attributed authorship of "The Jolly Gauger" to Burns; Delancey Ferguson believes that if it was not original with Burns it was probably touched up by him.

The tune first appeared in Oswald's "Caledonian Pocket Companion," book IX, page 16, under the title "The Beggar's Meal Pokes". Glen questions the frequently attributed antiquity of the tune and comments that " … the tune has modern stamped upon it … " (Glen, p. 147.)

The present text, with slight orthographic changes consistent with Scots pronounciation, was learned from MMC '59, p. 78 (originally from MMC 1800). The tune was learned from SMM, #266 ("The Jolly Beggar").

Gie The Lass Her Fairin' — This song is attributed to Burns in MMC 1827, by Scott Douglas in a pencilled note in MMC 1800, and by the editors of MMC '59 who supported the attribution with the statement "Quite likely too; the tune was one of his favourites." M'Naught does not appear to have supported this contention, however, for in MMC 'll, below the song title, he has the remark: "An old fragment."

Mr. Hamish Henderson, folklore collector and Research Fellow for the School of Scottish Studies, Edinburgh, reports that he heard this song in tradition during his youth in Perthshire.

The tune, "Cauld Kail in Aberdeen", was popular to various sets of words before it was published for the first time in SMM (1788), #162, to a song of the same title, contributed by Burns (see Dick, Songs, notes to #225, p. 431, and #102, p. 384.)

The present text was learned from MMC '59, p. 80 (originally from MMC 1800) and the tune from SMM, #162.

Supper Is Na Ready — The editors of MMC '59 consider this song to be one collected by Burns. M'Naught appears to agree with this in MMC 'll, for below the title of the song he has the remark: "This is an old fragment." One cannot, however, agree with him as to its being a 'fragment'; no song was ever more complete in making its point in two such short stanzas.

Mr. Gershon Legman, in correspondence to me in April, 1960, informed me that this song is "a translation from 16th century French," but was unable to supply me with his bibliographical reference for the statement at the time.

Burns was certainly familiar with the tune, "Clout the Cauldron", to which it is supposed to be sung. He knew it as the tune to "The Tinker" and "The Turnimspike" (see Cook, p. 12, for Burns' note on "Clout the Cauldron", and Dick, Songs, p. 447), and used it as the tune to the song beginning "My bonnie lass, I work in brass … " in the "Jolly Beggars" cantata, as well as for "The Fornicator" (MMC '59, p. 52).

"Supper Is Na Ready" appears to have continued in oral circulation in Scotland (though its ultimate source may well have been some edition of MMC), as the version sung here by Ewan MacColl was learned by him from the singing of his father, who had it from a fellow iron-moulder, Jock Smyllie. MacColl's version differs only in its refrain from the one published in MMC '59 (originally from MMC 1800).

Wad Ye Do That? — M'Naught (MMC 'll) referred to this piece as "An old song before Burns's time." It is certainly the original of Burns' song "Lass, When Tour Mither Is Frae Hame" (Aldine. II, p. 156), which Scott Douglas referred to as "a silly paraphrase" of the present song.

The tune, "John Anderson, My Jo," dates back at least to the middle of the 17th century.

It was certainly a favorite with Burns, who also knew it as the tune to a bawdy song of that title (MMC '59, pp. 114-115) on which he based his own song of the same name (SMM, #260), as well as the tune of "Our Gudewife's Sae Modest", another piece of bawdry collected by Burns (see MMC '59, p. 135).

The present text was learned from MMC '59, p. 122, and the tune from MacColl's father.

Andrew An' His Cutty Gun — The earliest published song of this name appeared in Allan Ramsey's TTM in 1740. James Dick referred to it as "a brilliant vernacular song" of which "many imitations have been written, but none equals the original … " (Dick, Songs. p. 361). The exact relationship of that song to the present one is in question; Dick was uncertain as to whether the bacchanalian song in TTM was "the original or a parody of verses in the Merry Muses." (Dick. Notes. p. 96).

Either the 'brilliant' bacchanalian piece or the present bawdy song was the original from which Burns fashioned his composition, "Blythe Was She" (SMM, 1788, #180). From Burns' own remarks in a letter to George Thomson in 1794, in which he described the bawdy song as "the work of a Master" (Letters. Vol. II, p. 276), it would appear that the present song was the original for his own creation.

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 120 (originally from MMC 1800); the tune was learned from MacColl's father,

Duncan Gray — Henley and Henderson (Centenary. Volume III, p. 452) and Hans Hecht (Hecht. p. 319) appear to be in agreement that the Merry Muse text of "Duncan Gray" was a Burns touch-up of a similar version appearing in David Herd's mss. (see Hecht, pp. 208-209). This may have been the case, but nowhere in his correspondence did Burns ever mention Herd by name, a very unlikely occurence if he had had access to Herd's mss. Indeed, the editors of the Centenary edition of Burns' works claim that Burns used twenty of Herd's unpublished songs as source material. Burns, however, was too scrupulous in such matters to pass over giving credit where it was due. A more logical answer is that given by Alexander Keith (Keith, p. 41): " … Burns was familiar with the songs, or variants of them, independent of Herd or any manuscript whatever. He and Herd were tapping the same flow."

Either the present text or its original (if there was one) was the basis for two of Burns' Scots dialect creations of the same name (SMM, #160, and Dick, Songs, pp. 160-161), and an inferior song to the same tune, in English, "Let Not Women E'er Complain" (Dick, Songs. p. 99).

Concerning the tune itself, Stenhouse (Illustrations. p. 148) reports a tradition that "this lively air was composed by Duncan Gray, a carter or carman in Glasgow, about the beginning of the last [l8th] century, and that the tune was taken down from his whistling it two or three times to a musician in that city."

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, pp. 98-99 (originally from MMC 1800); the tune was learned from MacColl's father.

I Rede Ye Beware O' The Ripples — In a pencilled note in MMC 1800, Scott Douglas attributed this version of an older song to Burns; Henley and Henderson concur with this (Centenary, Volume IV, p. 89). The song was the original of Burns' composition "The Bonnie Moor Hen" (Dick, Songs, p. 154) which Burns sent to Mrs. McLehose (Clarinda), and which she advised him not to publish.

The present song is sung to the tune of "The Taylor's faun thro the bed," the earliest appearance of which is in a manuscript music collection of 1694, where the tune is titled "Beware of the Ripells"; this certainly supports the contention that the song was known before Burns' time (Dick, Songs, p. 409). Burns contributed the song "The Taylor Fell Thro' the Bed" to SMM (#212), two verses of the song coming from his own pen (Dick, Notes, p. 43), and sung to the same tune.

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 83 (originally from MMC 1800), and the tune from SMM, #212.

The Trogger — M'Naught (MMC 'll) describes this song as "Anonymous; probably not older than Burns's time". However, Henley and Henderson (Centenary, Volume III, p. 415), Scott Douglas (in a pencilled note in MMC 1800), and James Barke and Sidney Goodsir Smith (MMC '59) are all in agreement that it was probably written by Burns.

The tune, "Gillicrankie", is also that given for two other Merry Muse songs, "Ellibanks"(MMC '59, pp. 108-109) and "Nae Hair On't" (MMC '59, p. 149), although we can not be sure that they were indeed sung to the same tune as there are several unrelated tunes of this same name.

The text was learned from MMC '59, p. 75 (Originally from MMC 1800), and the tune from James Hogg's Jacobite Relics, Volume I, pp. 32-33.

My Ain Kind Dearie — Henley and Henderson consider this song to be the basis of a song of the same name in SMM, #49, which they attribute to Burns (Centenary, Volume III, p.497). Burns, in the interleaved copy of SMM, indicates that the text printed there (for which he makes no claims) is less beautiful than the old words of the song which he states "were mostly composed by poor [Robert] Ferguson, in one of his merry humors." He follows this with one verse of the 'old words', which differs only slightly from the first verse of the present Merry Muses text (Dick, Notes, pp. 17-18). Hans Hecht, in commenting on two texts of "The Ley-Rigg" from David Herd's mss. (Hecht, pp. 100-101), refutes the claim made for Ferguson as its author, preferring to believe that Ferguson only transmitted it (Hecht, pp. 281-282).

Whether or not Burns was indeed the author of the song of this title in SMM, he certainly did use its tune for one of his own compositions, "When O'er the Hill the Evening Star" (see Dick, Songs, pp. 124-125). Dick indicates that the tune "probably belongs to the seventeenth century", but is unable to supply any references to it earlier than the middle of the 18th century (Dick, Songs, p. 397).

The present text was learned from MMC '59, p. 102 (originally from MMC 1800), and is sung to a tune which MacColl's parents used with the more conventional text.

The Bonniest Lass — This piece is certainly Burns' own composition; the theme is different, but it is of the same cloth as his deservedly world famous song, "Is There for Honest Poverty". It is Burns at his best in a lecturing mood, ranting against cant and hypocracy in matters concerning sex.

The tune, "For a' that", was a favorite of Burns. In addition to writing "Is There for Honest Poverty" to it, he also set to it the verses beginning "I Am A Bard of No Regard" in the "Jolly Beggars" cantata, which he later rewrote for publication in SMM as "Tho' Women's Minds Like Winter Winds" (see Dick, Songs, pp. 290-291, 228, and 69, respectively, for the three songs mentioned here.) James Dick reports that the tune "has been continuously popular since the middle of the eighteenth century," and gives several references to its publication (Dick, Songs, p. 475). It is also the tune for another Merry Muses song, "Put Butter In My Donald's Brose" (MMC '59, p. 76), which is sometimes attributed to Burns.

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 69 (originally from MMC 1827); the tune was learned from SMM, #290.

The Modiewark — This delightful piece of erotic symbolism was collected by Burns, and though the text itself was never used as the basis for any of his own compositions he apparently thought sufficiently of its tune to set his own verses to it. The song, "O, For Ane and Twenty Tam", was written by Burns specifically for SMM (#355), for which publication he directed it to be set to the tune "The Moudiewart" (Dick, Songs, p. 415).

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 144 (originally from MMC 1800), and the tune from SMM, #355.

Todlen Hame — The text of this song did not appear in any edition of the Merry Muses prior to its inclusion in MMC !59. In 1795 Burns sent it to his friend Robert Cleghorn, a fellow member of the Crochallan Fencibles, with the information that it was written by David McCulloch of Ardwell, Galloway (Letters, Volume II, p. 309).

Of the original song, "Todlen Hame", Burns wrote: "This is perhaps the first bottle song that ever was composed."(Dick, Notes, p. 51). It is the kind of song Burns would have admired, but he does not appear to have utilized either the text or tune for any of his own creations.

The song was first published in TTM in 1725 (see TTM, Volume I, p. 161), in Thomson's Orpheus Caledonius (1733), with a tune, and in SMM, #275, to a different tune. Both text and tune have appeared rather frequently in popular anthologies since that time.

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 61, and the tune from SMM, #275.

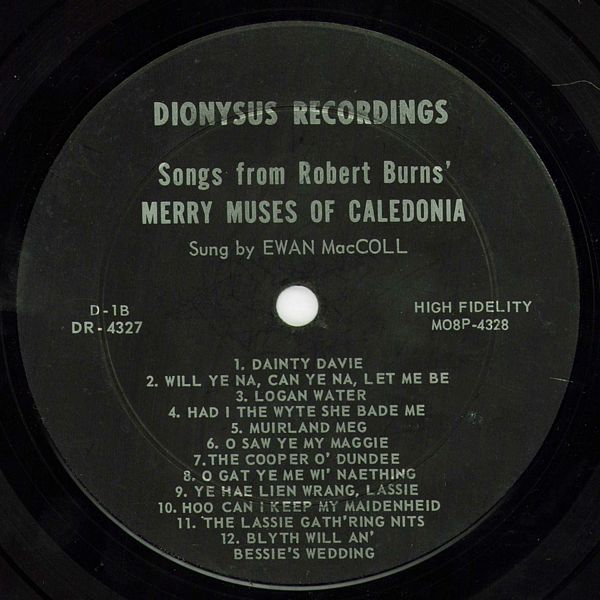

Dainty Davie — Hans Hecht, James Barke and Sidney Goodsir Smith are of the opinion that this text is Burns' own version of an old song published by David Herd (for their arguments in defense of this position see footnote in MMC '59, p. 74). I am inclined to disagree with these learned scholars about the matter of Burns' improving on Herd's published text. Herd (1776), Volume II, p. 215, prints a three verse text in a section called "Fragments of Comic and Humorous Songs". In his only known reference to Herd (see Cook, p. 12), Burns wrote: "A mutilated stanza or two are to be found in Herd's Collection, but the song consists of five or six stanzas, and has merit in its way." He then quotes a first stanza differing only in its last line from the Merry Muses text. When reworking some older song Burns usually gave proper credits, sometimes even indicating which lines or stanzas were his own. Having made reference to Herd's fragmentary text, why should he have found it necessary to invent the story of there being a longer version? Hecht's arguments are based on the fact that the Merry Muses text is more precise in telling its story and in making clear the allusion to the proper name Cherrytrees. He then states that "comparison makes it clear that the version of Dainty Davie in MMC was derived from the version given by Herd with express artistic intentions. There is no doubt whatever that Burns himself was the author of these changes." I am not convinced. Anyone familiar with the ways of traditional songs in Scotland would be aware of the fact that imprecise fragmentary versions of a song exist side by side with more exact, fuller texts in a folk-singing community. Tradition in a well established folk community is rather conservative, with the more literate and literary folksingers in the community tending to correct and reestablish the more degenerate and fragmentary texts into a more perfect whole. The "express artistic intentions" which had reshaped a fragmentary text could well have been those of any intelligent folk-poet (of which Scotland, with the most literate peasantry in the English-speaking world, has had thousands in past days), and need not necessarily have been the handiwork of Burns himself. The text which Burns knew could well have come to him from some folk source. To again quote Keith: "He and Herd were tapping the same flow." Burns may indeed have touched up any traditional song which came his way in order to "heighten the artistic effect," but the version which he knew could have come from a traditional singer of his acquaintance, and could have been a more "perfect" text than that published by Herd, in which case Burns' enroachments on the text would have been of a far lesser order than that in which he had to indulge if he was repairing Herd's fragmentary text to arrive at the Merry Muse text.

Burns thought highly of the song and of the anecdote which gave rise to it (see Dick, Songs. p. 474) and stated: " … were their delicacy equal to their humor, they would merit a place in any collection" (Dick, Notes. p. 12). He utilized its chorus and tune in his song "Now Rosy May Comes in Wi' Flowers" (Dick, Songs, p. 123). To its tune he also wrote "There Was A Lad Was Born in Kyle", which has, however, come down to us usually sung to the tune "O An' Ye Were Dead, Gudeman" (see Dick, Songs. p. 289 for the latter song to the "Dainty Davie" tune). The tune has been traced to the end of the 17th century, and was published rather frequently thereafter in both English and Scottish collections (see Glen, p. 68, and Dick, Songs. p. 474).

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 74 (originally from MMC 1800), and the tune from SMM, #34.

Will Ye Na. Can Ye Na, Let Me Be — The editors of MMC '59 have included this song under the section of "Old Songs Used by Burns for Polite Versions" on the basis that its first line was paraphrased by Burns in his song "Scroggam" (SMM, #539). The first line of the latter song reads:

"There was a wife wonn'd in Cockpen, Scroggam … "

Otherwise the two songs bear no relationship to each other. Nor does Burns appear to have used any other part of the song for his own creations.

The present song is such a perfect lyric in every way that I am led to believe that it may well be Burns' own composition, in one of his more playful moods. Until some variant text is reported from tradition or print this should be considered a definite possibility.

The tune, "I Ha'e Laid A Herrin' in Sa't", was certainly familiar to Burns, as it appeared in SMM, Volume III (1790), under the title "Lass, Gin Ye Lo'e Me, Tell Me Now," the tune's title being taken from the first line of the song. The song itself appeared in Herd (1776), Volume II, pp. 225-226, and, according to Hecht, Herd's text was 'recast' by James Tytler for SMM (see Hecht, p. 283). For the history of earlier related texts printed in England, see Wm. Chappel's introductory note to the broadside "The Countryman's Delight" in the Roxburghe Ballads. Volume III, pp 590-592.

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 107 (originally from MMC 1800); the tune was learned from SMM, #244.

Logan Water — Sidney Goodsir Smith, in comparing this text with a variant published by Herd, indicates his belief that "..variations here are most probably improvements made by Burns in transcribing" (MMC '59, p. 100). This need not have been the case. The same arguments which I put forward in the notes to "Dainty Davie" apply to this song as well. And, in addition, the text is so short and of the kind which strongly impresses itself on the memory, that the very slight variations between the Herd and Merry Muses text would be a common thing in oral tradition. Indeed, I found the first verse in living tradition in Scotland in 1959:

"It's Logan wids an' Logan braes,

Whaur I helped a bonnie lassie on wi! her claes;

First her hose an' then her sheen —

She gied me the slip fen a' wis deen."

— Collected in Fetterangus, Aberdeenshire, December 30, 1959.

The variations between the Merry Muse text and the traditional text are relatively minute when one considers that the former text is over 150 years older than the verse given above.

Henley and Henderson (Centenary, Volume III, p. 485) consider the present song to be the origin of Burns' song of the same name (Dick, Songs, pp. 252-253). However, aside from its tune, there is no apparent relationship between the two songs. Burns wrote to Thomson that he knew "a good many different" songs of "Logan Water", and he apparently fashioned his own song after one by John Mayne (see Dick, Songs. p. 458). There is also another song, "The Bower of Bliss", to this tune in MMC '59, p. 160.

The tune may trace back to the 17th century, as various English broadsides of that period were instructed to be sung to the tune "Logan Water". The time appeared frequently in Scottish collections during the 18th century and has been printed often since that time (Dick, Songs, p. 458).

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 100 (originally from MMC 1800), and the tune from SMM, #42.

Had I The Wyte She Bade Me — Henley and Henderson (Centenary. Volume III, p. 411) write: "The inference is irresistable that the fragment in the Herd ms [Hecht, p. 117] suggested two songs to Burns: one for publication, the other — not." Hecht is in agreement with this (Hecht, p. 288) and James Barke and Sidney Goodsir Smith indicate their approval of this evaluation. But until it can be proven that Burns actually saw the Herd mss., the claim is pure conjecture. Again, as in the case of "Dainty Davie" and "Logan Water", Burns could have gotten hold of another and more complete version from tradition. Sir Walter Scott appears to have known another version, for in a marginal note to Herd's text he wrote: "For the last two lines read

And when I could na do't again: Silly loon she ca'd me."

— Hecht, p. 117 [repeated in MMC '59, p. 9l]

Note that these two lines are a variant of lines 5 and 6 in the first verse of the Merry Muses text, but are nowhere present in the Herd text. Are we to assume that Scott also was reworking Herd's text? If so, isn't it strange that he should arrive at two lines which are closely related to two lines which are supposed to be the handiwork of Burns? More than likely, both Burns and Scott had heard other traditional versions which may have been related, but which were certainly different from the Herd ms. text.

There is no question that the Merry Muses song did suggest Burns' own composition of the same name, which was published in SMM, #415. According to Dick, the tune can be traced to the beginning of the 18th century and was known by various other titles in addition to "Highland Hills" (to which the Merry Muses text is instructed to be sung). The tune was printed frequently in the 18th century, and its popularity has come down to this century (see Dick, Songs, p. 418). I heard the tune played on the harmonica in northeastern Scotland in 1960.

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 73 (originally from MMC 1800), and the tune from SMM, #415.

Muirland Meg — Only a handful of Merry Muses texts have come down to us in Burns' own handwriting. "Muirland Meg" is one of these, and the present text is probably one collected by Burns' from tradition.

"Muirland Meg" is instructed to be sung to the tune "Saw Ye My Eppie McNab", the title song of which is also to be found in MMC '59, p. 97. This latter song was undoubtedly the origin of Burns' song of the same title (Dick, Songs. p. 114). The tune has been traced back to 1742, but Dick believes that "From its construction it is much older than the earliest date named" (Dick, Songs, p. 394).

The present text was learned from MMC '59, p. 60 (originally from a holograph text in Burns' handwriting, but incorporating the chorus with which it appeared in MMC 1800). The tune was learned from SMM, #336.

O Saw Ye My Maggie? — This song is an old form of "Saw Ye Nae My Peggie" which Johnson published in SMM, #11 (borrowed from Herd (1769), p. 175, or Herd (1776), Vol. I, pp. 288-289). In the interleaved SMM, Burns says of "Saw Ye Nae My Peggie": "There is another set of the words, much older still, and which I take to be the original one, but though it has a great deal of merit it is not quite ladies reading" (Dick, Notes. p. 4). In another set of comments, he specifically identifies this 'older' version, referring to it as "a song familiar from the cradle to every Scotish ear: — ", and then follows three verses of the present song (Cook, pp. 9-10). Dick attempts to establish the age of the song by reporting that it is named in an account of witchcraft trials in the year 1659 (Dick, Notes, p. 83).

The tune, "Saw Ye Nae My Peggy", has been traced by Dick to a manuscript of 1694, and then appears in Orpheus Caledonius, 1725 and 1733, from which the SMM tune was borrowed (Dick, Notes, p. 83). There is another song, "O Gin I Had Her", sung to the same tune, which appears in MMC '59, p. 155.

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, pp. 48-50 (originally from a holograph ms. which omitted stanza 3; the missing stanza and the order in which the stanzas are sung here are as they appeared in MMC 1800). The tune was learned from SMM, #11.

The Cooper O' Dundee — The editors of MMC '59 include this song under section three, "Old Songs Used by Burns for Polite Versions", and indicate it as being "an old version of "Whare gat ye that happed meal-bannock."" I see absolutely no relation between this song and the one named, except in their common use of the same tune, and Dundee as the place of action. Burns' song, "O Whar Got Ye That Hauver-Meal Bannock" (SMM, #99, entitled "Bonnie Dundee") was his own rewrite of some old song which was perhaps related to an old broadside with the same opening lines (for a version of this broadside see A Collection of Old Ballads, Volume I, pp. 275-277) and concerning the affairs of a soldier and a parson's daughter. Neither Burns' song or the old broadside from which it may have been derived are in any way related to the present song from the Merry Muses.

"The Cooper o' Dundee" is one of a large group of bawdy songs in printed and oral tradition which make use of euphemistic references to sexual intercourse, utilizing industrial or trade terminology for the various actions and organs.

The tune, "Bonny Dundee" (or "Adieu Dundee"), has been traced back to the beginning of the 17th century, and was popular both in England and Scotland from at least the end of the 17th century, appearing as the tune to numerous broadside and drollery songs, as well as for use as a dance tune (Dick, Songs, p. 389). A second song in the Merry Muses, "Cuddie the Cooper" (MMC '59, p. 148), utilizes both the same tune and trade euphemisms.

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 105, and the tune from SMM, #99.

O Gat Ye Me Wi' Naething — This song may be the original of "The Lass of Ecclefechan" (SMM, #430), from which it differs in only the last five lines of the first stanza. Though not marked as such in SMM, Stenhouse (Illustrations. p. 381) indicates that the latter song is the work of Burns, and most modern editors have agreed with this. If such is the case then the present song from the Merry Muses is probably Burns' composition, as well. Henley and Henderson (Centenary, Volume III, p. 156) and Scott Douglas (in a pencilled note in MMC 1800) are of this opinion. The possibility exists that the present text is substantially as Burns collected it from tradition, and that he found it necessary to amend only five lines for publication in SMM. Sidney Goodsir Smith suggests that it "might well be by Burns on the basis of an old fragment, probably the first two lines" (MMC '59, p. 79).

Dick traces the tune, "Jacky Latin", from the middle of the 18th century, and prints the first stanza and chorus of a song "of uncertain age" whose hero is "Bonie Jockie Latin" (Dick, Songs. pp. 418-419).

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 79 (originally from MMC 1800); the tune is from SMM, #430.

Ye Hae Lien Wrang, Lassie — This song was probably collected from tradition by Burns. It is certainly the origin of his fragmentary song of the same title (Aldine, Volume II, p. 155), which contains the chorus and third verse, considerably altered, of the present song.

The tune, "Up and Waur Them a', Willie", is that of a song of the 1715 Rebellion which Burns rewrote in part for inclusion in SMM, #188. Dick traces the tune from the middle of the 18th century (Dick, Songs, p. 465).

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 106 (originally from MMC 1800), and the tune from SMM, #188.

Hoo Can I Keep My Maidenheid — The editors of MMC '59 consider this song to be the original of Burns' song "O Wat Ye What My Minnie Did" (Aldine, Volume II, p. 157), but I am inclined to view that as an unrelated song sharing only its tune and metrics, and which may not have been written by Burns at all; it appears in a manuscript in Burns' handwriting which contains his notes on various songs together with texts which are not of his own composition (Cook, p. 7). It would appear, in any case, that the present song was one of the bawdy songs which Burns collected from tradition.

Another version of this song was published by C. K. Sharpe in 1823 (Sharpe, pp. 54-55), and may date back to Burns' time. In his notes to the song, Sharpe indicates that "Nancy Anderson, our nursery-maid in old times, used to sing this very well. It was a prodigious favourite among the nymphs of Annandale" (Sharpe, p. 130).

Hamish Henderson informed me that the song was in oral circulation during his childhood days in Perthshire. The song continues to live in oral tradition; I collected two fragmentary texts in northeastern Scotland in December 1959 containing substantially the lines of the first two verses of the Merry Muses text.

The tune, "The Birks o' Abergeldie", was utilized by Burns for a song of the same name which he wrote for SMM, #113. Dick traces the tune back to the end of the 17th century, after which it was printed rather frequently in the 18th century (Dick, Songs, p. 389).

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 119 (originally from MMC 1800); the tune is from SMM, #113.

The Lassie Gath'ring Nits — This tender bit of bawdry was probably collected by Burns from tradition. He does not appear to have used it as the basis for any of his own compositions.

A chanted street rhyme from my childhood in Brooklyn, New York, told a similar story:

I saw a girl who fell asleep,

Eerie, eerie, orie,

When up to her four boys did creep,

Eerie, orie, aye.

The first he touched her on the breast,

I leave it to you to guess the rest.

The second he touched her on the thigh,

I leave it to you to guess how high.

The third he touched her on the hair,

I leave it to you to guess just where.

The fourth he touched her not at all,

But what he did I will not tell.

— circa 1936.

Mr. Hamish Henderson, in correspondence to me in December, 1960, informed me that "The Lassie Gath'ring Nits" corresponds, stanza by stanza to a modern French bawdy song, "Jeanneton prend sa faucille":

Ce que fit le dernier

N'est pas dit dans la chanson.

The present song is instructed to be sung to the tune, "O the Broom". I take this to be the tune commonly associated with "The Brook of Cowdenknowes", the chorus of which begins: "O the broom, the bonnie, bonnie broom,/ The broom of Cowdenknowes … ". Dick traces the tune back to the middle of the 17th century and reports its inclusion in "numerous Scottish collections of the eighteenth century" (Dick, Notes, p. 89). It is also given as the tune to another Merry Muses song, "Johnie Scott" (MMC '59, p. 153).

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 151 (originally from MMC 1800); the tune was learned by MacColl from his father's singing of "The Broom of Cowdenknowes".

Blyth Will An' Bessie's Wedding — This song was probably collected from tradition by Burns. At least part of the song has continued into modern tradition. I collected a close variant of the last verse in Aberdeenshire in 1959, and in a letter from Hamish Henderson in December, 1960, the following stanza was enclosed which Mr. Henderson informed me as occurring by itself or with other verses in the bawdy song "Tail Toddle" (for a version of which see MMC '59, p. 82):

"Twa and twa made the bed,

Twa and twa lay doon thegither;

Fin the bed begin tae heat,

The teen lay on abeen the tither."

In a letter from Gershon Legman in April, 1960, he indicated that he considered "Blyth Will as still in tradition, under the title The Ball o' Kirriemuir!". The connection is not as tenuous as it may seem on first glance, for certainly both songs are in the same spirit, and several of the verses given here would find themselves quite at home in "The Ball of Kirriemuir".

The tune, "Roy's Wife" is also known as "Ruffian's Rant" and under that title is suggested as the tune for "Cornin' o'er the Hills o' Coupar" (see MMC '59, pp. 110-111) which contains stanzas very much in the same spirit as the present song. In MMC 1800, three stanzas which originally belonged to the latter song were included in the text with "Blyth Will"; the editors of MMC '59 have set the matter straight,

Dick traces this song back to about 1740 (Dick, Songs. p. 442); Glen informs us that "the air is considerably older" without citing any earlier collections or mss. in which it appeared (Glen, p. 168),

The text sung here was learned from MMC '59, p. 131 (originally from MMC 1800); the tune was learned from the singing of MacColl's father to the usual "Roy's Wife of Aldivaloch" text.