|

|

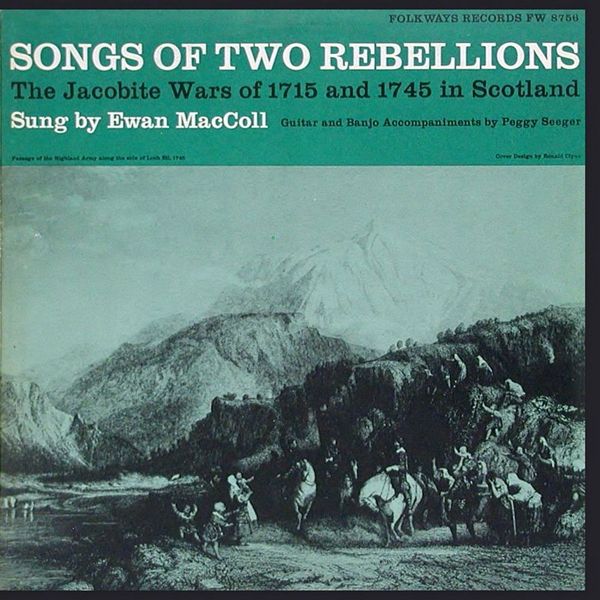

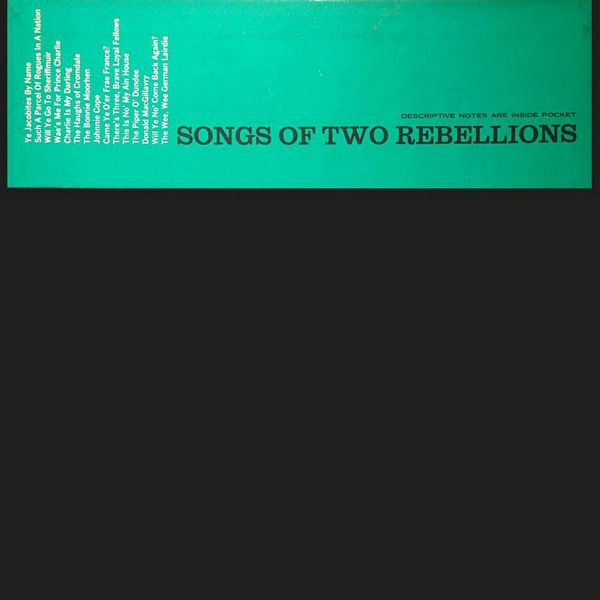

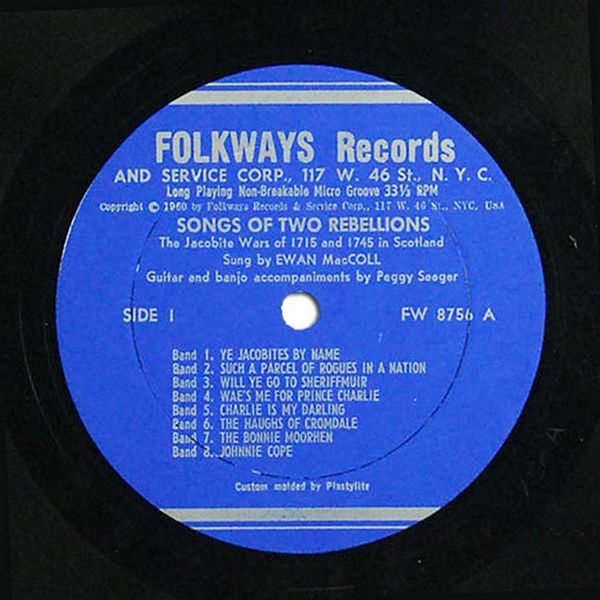

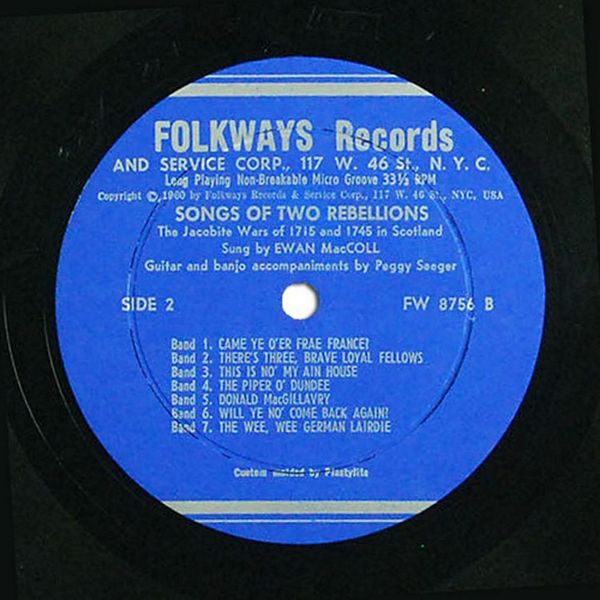

Sleeve Notes

Two Jacobite Rebellions

During the eighteenth century, Scotland, like many countries of western Europe, experienced a profound economic, social, religious and political revolution. In the early years of the century she was an agrarian, politically Independent nation; at the end she was heavily Industrialized and politically bound to England. The old system of lands worked by the peasantry in feu to the great landowners had been smashed and supplanted by Industrial capitalism. The political bond with England had destroyed the traditional "Auld Alliance" with France, that had helped sustain Scotland when she was Independent. Great urban centers of trade and manufacturing had developed, and the earlier extreme poverty of the Scottish people had been tempered a little by some prosperity.

Revolution did not occur without bewllderlngly sudden changes, harsh reverses, bloodshed, and great suffering.

Who can guess what course Scottish development would have taken without the Intervention of England? The aim of English policy had always been to dominate Scotland, to use and exploit her people and resources, and, as a necessary prerequisite, to suppress and even destroy her national aspirations and native culture. With the Union of the Parliaments (1707) It seemed that success was finally with England. But Scottish resistance continued to live, resulting in a series of armed rebellions, of which those of 1715 and 1745 were the most Important.

These rebellions were conducted by the Jacobites, adherents of James II and his descendants, who took as their first aim In both rebellions the restoration of the Stuarts to the throne of Scotland and England In place of the Hanovers. The Jacobites won the support of large sections of the Scottish people. There were supporters among some merchants whose trade had been ruined by the Union. There were patriotic Scots who longed for complete Independence and a return of the French alliance. There were Catholics, mainly In the Highlands, who wanted a return of the Catholic Stuarts.

Nevertheless, the broadest elements of Scottish life failed to support the Jacobites, particularly In the first Insurrection. It was an unfortunate fact, but quite understandable considering the time, that the struggle for Independence was led by representatives of the old feudal system who could not possibly rally the Scottish people entirely. As a struggle for the national existence, the wars took on nobility of purpose; but as an effort to restore an old system that had been supplanted by a better, they could not unify Scotland. This fact, combined with Inferior military leadership and the failure of expected French aid to appear, swiftly doomed the rebellion of 1715.

At Preston five thousand Jacobites, three armies, were surrounded and captured or dispersed. Soon thereafter, the chief Jacobite military leader, the Earl of Mar, led an army toward Stirling, the way to which was barred by the English force under the Scottish Duke of Argyle. They met at Sheriffmuir, near Dunblane, and fought a near draw. But since the Jacobites withdrew, leaving Argyle still barring the way to Stirling, the result was a defeat for the Jacobites. Prince James's arrival In Scotland the next month did nothing to rally the Jacobites, and he slipped away again to France, ending the Fifteen.

A brief rebellion flared in 1719. This was quickly crushed with the defeat of the Jacobites in the Pass of Glenshiels, in Ross-shire. More than twenty-five years later the greatest rebellion of all occurred — one that came very near success. This began on July 25, 1745, when Prince Charles Edward, son of James, landed In Scotland. Charles was a more forceful figure than his father. He was young and courageous and not without military ability; these attributes helped draw to the cause many Scots who might otherwise have been Indifferent. Besides, Bonnie Prince Charlie, unlike his father, came to help lead the military campaigns. Most of the clan chiefs joined him, and In August the Jacobite standard was raised.

Under Lord George Murray, an excellent strategist, the Jacobites marched boldly on Edinburgh and seized the city before the English could prevent them. The English leader, General John Cope, brought his troops Into Dunbar; but the Jacobites forced the Issue with a fierce dawn attack at Prestonpans, between Edinburgh and Dunbar, and routed Cope and his men. Prince Charles set up court at Holyrood Palace. Against the counsel of some of his advisors, there he wasted a number of weeks while the Hanoverians reorganized.

When the Jacobites finally moved, they Invaded England as far south as Derby, but failed to draw the North Country to their banner as they had hoped to do. English armies came in pursuit as the Jacobites retreated through the border country, the Lowlands, and back to their mountain glens. This time the English were determined to wipe out rebellion and the spirit of rebellion. The English leader, the Duke of Cumberland, dubbed "The Butcher" by the Scots, led the Redcoats In a campaign of pillage, rape and murder as they drove through Scotland. The last battle was fought at Culloden Moor, near Inverness, where the Jacobites suffered a crushing defeat that ended the Forty-Five.

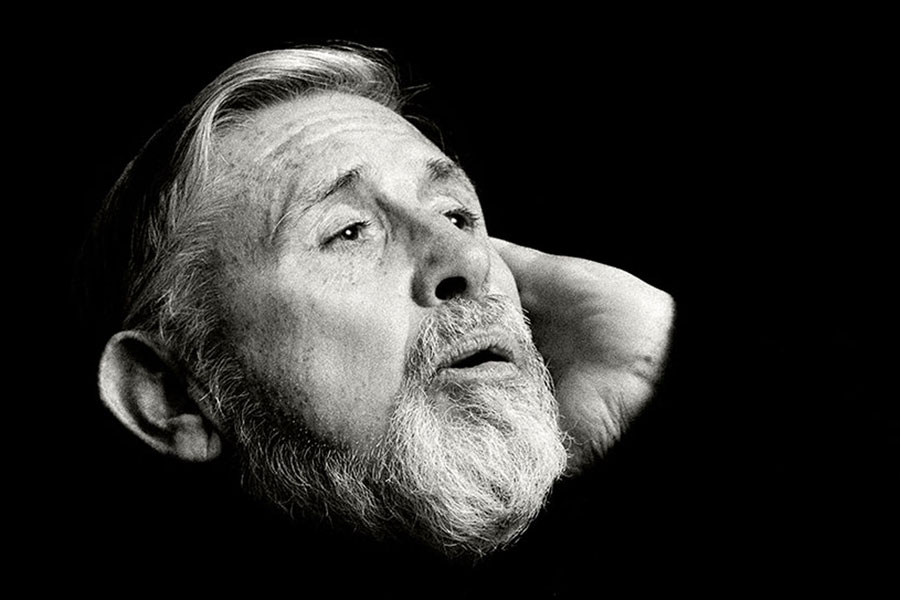

Whatever may have been the shortcomings of the Jacobite rebellions, or however ingloriously they may have ended, they and Bonnie Prince Charlie, to the Scots, remained as one of the peaks of national life. In the Jacobite songs every battle became a cry against oppression, and every leader wears the aspect of Ideal courage, boldness and strength, without blemish. The songs are glorious. Through them the Jacobites have won their rebellions, for the songs exist In posterity, moving us who are so far removed from the events, the causes, and the feelings, of the Fifteen and the Forty-Five; who live In other countries and pursue other destinies. As Ewan MacColl writes: "To a world which has become familiar with the concept of genocide, which has known fascism and two world wars, the Jacobite rebellions appear as no more than cases of mild unrest. They have grown dusty in history's lumber room along with all the other lost causes. The Stuart cause is forgotten and nothing, remains of it except the songs. "And what songs they are'. Witty, tender, proud, bitter, ribald, delicate, passionate; the songs of a people with a great zest and appetite for life; the songs of a people who are essentially optimistic and who, oddly enough, succeed In combining sympathy for a declining royal house with the most republican sentiments."

Ralph Knight

Notes and Glossaries

YE JACOBITES BY NAME — The air of this song has always been popular in Scotland and is sung to many different songs on many different subjects, but, according to James Hogg, 'none of them are Jacobite save this.'

fauts, faults; maun, must.

SUCH A PARCEL OF ROGUES IN A NATION — This song embodies rather well the anti-Union feeling of Scotland during the eighteenth century. The charge of corruption which is made here against the majority of the Scottish Parliament who 'treasonably sold us for English gold', is repeated again and again in the Jacobite songs.

rins, runs.

WILL YE GO TO SHERIFFMUIR — The victory at the battle of Sheriffmuir, fought between the clans under the Earl of Mar and the Hanoverian forces under the Duke of Argyle on the 13th November 1715, has been claimed by both sides. Winners or losers, the Jacobites celebrated the battle in a number of fine songs, of which this is probably the least well known. There is some doubt among clan historians as to the identity of Bauld John o'Innisture.

ri'en, torn; hools, clothing; girnin gools, weeping melancholies; bauld, bold; gin, if, sic, such.

WAE'S ME FOR PRINCE CHARLIE — In spite of the harsh repressive measures which followed the collapse of the Forty Five rebellion, Scots ballad makers continued to extoll the virtues of Prince Charles for almost another hundred years. This song is the work of William Glen, born Glasgow in 1789. It is set to the ballad tune Gypsy Davy.

dule, sadness; ilka, every; row'd, wrapped.

CHARLIE HE'S MY DARLING — In these days, when it has become the custom to debunk the popular figures of other days, we are presented with a picture of the Young Pretender that is by no means agreeable. The shabby, and not quite sober, mendicant who haunted the back staircase of Versailles and who was not over scrupulous in his dealings with women, is not the Young Chevalier of the songs. For a great many Scots people. Charles Edward Stuart was not only a king and a leader but a living compendium of all the qualities which the Scots find commendable. The text given here is the original. Hogg wrote a modern and less forthright version of the song.

brawly weel be kend, very well he knew; daurna gang, dare not go.

THE HAUGHS OF CROMDALE — Poetic licence has been strained to breaking point in this vigorous ballad. The battle fought upon the plains of Cromdale in Strathspey did, in fact, result in the army of 1,500 Highlanders being defeated by Sir Thomas Livingstone's Hanoverians. Montrose, the hero of the song, was not present at the event. Some forty-five years before, however, he won a victory at the Battle of Auldearn against the Whig forces and it is probable that the two events have been dovetailed to provide us with a line, optimistic, if somewhat chronologically inaccurate song. The tune is a geat favourite with pipers. Haughs, level ground beside a stream: speer'd, asked.

THE BONNIE MOORHEN — Nearly ail the Jacobite songs were proscribed. Consequently, songwriters and singers tended to codify their verses. Charles Stuart appears in the songs in a host of disguises: as a blackbird, as 'our guidman' and, in this song, as a moorhen. The colours mentioned in the second verse allude to those found in the Clan Stuart tartan.

but, outside; ben, inside.

JOHNIE COPE — This song, still very popular with singers, fiddlers and pipers, refers to the Battle of Prestonpans. There the Jacobite army, commanded by Prince Charles in person, routed a numerically superior English force led by General John Cope. The event took place on September 21, 1745, but Scots singers still derive singular pleasure from recalling the outcome of the battle.

waukin, waking; C'wa, come away; hale, whole; blate, bashful; fogs, blows; claymores and filabegs. Highland swords and kilts.

CAME YE O'ER FRAE FRANCE — When George the First imported his seraglio of impoverished gentlewomen from Germany he provided the Jacobite songwriters with material for some of their most ribald verses. Madam Kilmansegge, Countess of Platen, is referred to exclusively as 'The Sow' in the songs while his favourite mistress, the lean and haggard Madame Schulemberg, later Duchess of Kendal, was given the name of 'The Goose.' She is the goosie in the song. The 'blade' mentioned in the second verse is the Count Koningsmark. 'Bobbing John' is a reference to John, Earl of Mar, who, at the time this song was made, was recruiting Highlanders for the Hanoverian cause. 'Geordie Whelps' is, of course, George the First.

kittle house, a house for dancing, a brothel; linkin, tripping along; niffer, haggle, exchange; tint, lost; has and maillins, houses and farmlands; belyve, quickly, burdie, buttock; brawly, well.

THERE'S THREE BRAVE, LOYAL FELLOWS — James Hogg suggests that this is a Highland song made on the eve of the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689. Certainly the air is more characteristic of Gaelic Scotland than of the Lowlands. The Lindsay mentioned in the song is probably Colin, Earl of Balcarras and the 'true MacLean' is surely the young Chief of Skye who played such a valiant part at Killiecrankie. 'Macrabrach' is possibly a mis-spelling of M'Abrach, the Laird of Coll. The unnamed gallant who succeeds Lindsay in the song could be Alaster MacDonald of Glengary, who carried King James' standard at the battle of Killiecrankie.

THIS IS NO MY AIN HOUSE — This beautiful song, written in the form of an allegory, is a perfect example of the skill shown by the Jacobite songwriters. The 'house' referred to is, of course, Scotland; 'my daddy' is the exiled Stuart king; and the 'cringing foreign goose" is the Hanoverian usurper.

carle, worthless fellow; ain, own; biggin, building; unco, illformed; downa, cannot; triggin,decoration; wi' routh o' kin and routh o' reek, with such a large family and so much bustle; door cheek, door step; claucht, seize.

THE PIPER O' DUNDEE — The identity of The Piper is unknown though Sir Walter Scott suggests that the notable Carnegie of Phinhaven would be a likely candidate. All those mentioned in the song were leading men of the Jacobite faction. Amulrie, where the meeting takes place, is a remote village in Central Perthshire.

spring, dance; fain, willing; muckle, great; queer, choir: gat, have; mad their lane, on their own.

DONALD MACGILLAVRY — James Hogg, in his Jacobite Relics, places this song as belonging to one of the risings, either 1715 or 1745. MacGillavry of Drumglass is one of the chiefs mentioned in the Chevalier's Muster Roll of 1715; and in the Forty-Five rebellion the powerful clan of M'Intosh was lead by a Colonel MacGillavry. On the other hand, the name might have been used as a convenient designation for loyal Highlanders.

gouk's nest, cuckoo's nest; weigh bauk, scales; wud, mad; elwand, measuring rod; rief, banditry; callan, fine fellow; lingel, shoemakers thread; mumpit wi' mirds, lulled with flattery; blads, large portions: flyting, scolding.

MACLEAN'S WELCOME — This song of greeting sets forth in flowery terms the Highland delights prepared for Prince Charles Edward Stuart's coming by a clan chieftain. In spite of the dubious part played by a Maclean prior to the rising of 1715, the Clan Maclean regiment fought bravely in the front line at the disastrous Battle of Culloden and sustained grievous losses. WILL YE NO COME BACK AGAIN? — This is by far the most popular Jacobite song sung in Scotland today. It is used as a parting song for all occasions.

merl, nightingale; lav' rock, lark.

NOTES BY EWAN MacCOLL