|

|

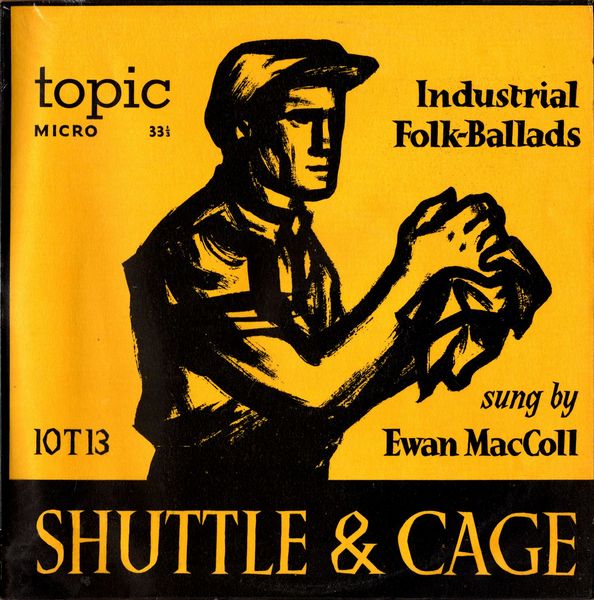

Sleeve Notes

There are no nightingales in these songs, no flowers — and the sun is rarely mentioned, their themes are work, poverty, hunger and exploitation. They are songs of toil, anthems of the industrial age.

Few of these songs have ever appeared in print before the collection "Shuttle and the Cage" (W.M.A. 2/.) was pubilished, for they were not made with the eye to quick sales, or to catch the song-plugger's ear, but to relieve the intolerable daily grind.

The folklore of the industrial worker is still a largely unexplored field. A comprehensive survey of our industrial folk-song requires the full collaboration of the Trade Union movement. Such a survey would, undoubtedly, enrich our traditional music.

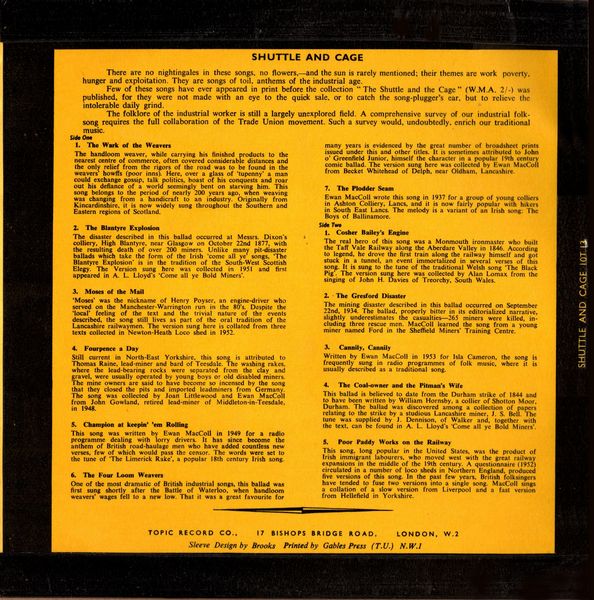

The Wark of the Weavers The handloom weaver, while carrying his finished products to the nearest centre of commerce often covered considerable distance, and the only relief from the rigors of the road was to be found in the weavers howffs (poor inns). Here over a glass of 'tupenny' a man could exchange gossip, talk politics, boast of his conquests and roar out his defiance of a world seemingly bent on starving him. This song belongs to the period of nearly 200 years ago, when weaving was changing from a handicraft to an industry. Originally from Kincardinshire, it is now widely sung throughout the southern and Eastern regions of Scotland.

The Blantyre Explosion The disaster described in this ballad occurred at Messrs. Dixon's colliery,. High Blantyre, near Glasgow on October 22nd 1877, with the resulting death of over 200 miners. Unlike many pit-disaster ballads which take the form of Irish 'come ye all' songs, The Blantyre Explosion is in the tradition of the South-West Scottish Elegy. The version sung here was collected in 1951 and first appeared in A. L. Lloyd's 'Come all ye bold Miners'.

Moses of the Mail 'Moses' was the nickname of Henry Poyser, an engine-driver who served on the Manchester-Warrington run in the '80s. Despite the 'local' feeling of the text and the trivial nature of the events described, the song still lives as part of the oral tradition of the Lancashire railwaymen. The version sung here is collated from three texts collected in Newton-Heath Loco shed in 1952.

Fourpence a Day Still current in North-East Yorkshire, this song is attributed to Thomas Raine, lead-miner and bard of Teesdale. The washing racks, where the lead-bearing rocks were separated from the clay and gravel were usually operated by young boysa or old disabled miners. Mine owners were said to have become so incensed by the song that they closed the pits and imported leadminers from Germany.

The song was collected by Joan Littlewood and Ewan MacColl from John Gowland, retired lead-miner of Middleton-in-Teesdale in 1948.

Champion at Keeping 'em Rolling This song was written by Ewan MacColl in 1949 for a radio programme dealing with lorry drivers. It has since been the British road-haulage men who have added countless new verses, few of which would past the censor, The words were set to the tune of 'The Limerick Rake', a popular 18th century Irish song.

The Four Loom Weavers One of the most dramatic of British Industrial songs, this ballad was first sung shortly after The Battle of Waterloo, when handloom weavers' wages fell to a new low. That it was a great favourite for many years is evidenced by the great number of broadsheet prints issued under this and other titles. It is sometimes attributed to John o' Greenfield Junior, himself the character in a ppoular l9th century comic ballad. The version sung here was collected by Ewan MacColl from Beckett Whtiehead of Delph, near Oldham, Lancashire.

The Plodder Seam Ewan MacColl wrote this song in 1937 for a group of young colliers in Ashton Colliery, Lancs, and it is now fairly popular with hikers in South East Lancs. The melody in a variant of an Irish song: The Boys of Ballinamore.

Cosher Bailey's Engine The real hero of this song was a Monmouth ironmaster who built the Taff Vale Railway along the Aberdare Valley in 1846. According to legend he drove the first train along the railway himself and got stuck in a tunnel, an event immortalised in several verses of this song. It is sung to the tune of the traditional Welsh song 'The Black Pig. The version sung here was collected by Alan Lomax from the singing of John H. Davies of Treorchy, South Wales.

The Gresford Disaster The mining disaster described in this ballad occurred on September 22nd 1934. The ballad, properly bitter in its editorialised narrative, slightly underestimates the casualties — 265 miners were killed, including three rescue men. MacColl learned the song from a young miner named Ford in the Sheffield Miners' Training Centre.

Cannily, Cannily Written by Ewan MacColl in 1953 for Isla Cameron, The song in frequently sung in radio programmes of folk music, where it in usually described as a traditional song.

The Coal-owner and the Pitman's Wife This ballad is believed to date from the Durham strike of 1844 and to have been written by William Hornsby, a collier of Shotton Moor, Durham. The ballad was discovered among a collection of papers relating to the strike by a studious Lancashire miner, J.S. Dell. The tune was supplied by J. Dennison. of WaIker and together with the text can be found in A.L Lloyd's 'Come all ye Bold Miners'.

Poor Paddy Works on the Railway This song, long popular in the United States, was the product of Irish immigrant labourer, who moved west with the great railway expansions in the middle of the 19th century. A questionnaire (1952) circulated to a number of loco sheds in Northern England produced five versions of this song. In the past few years British folksingers have tended to fuse two versions into a single song. MacColl sings a collation of a slow version from Liverpool and a fast version from Hellefield in Yorkshire.