|

|

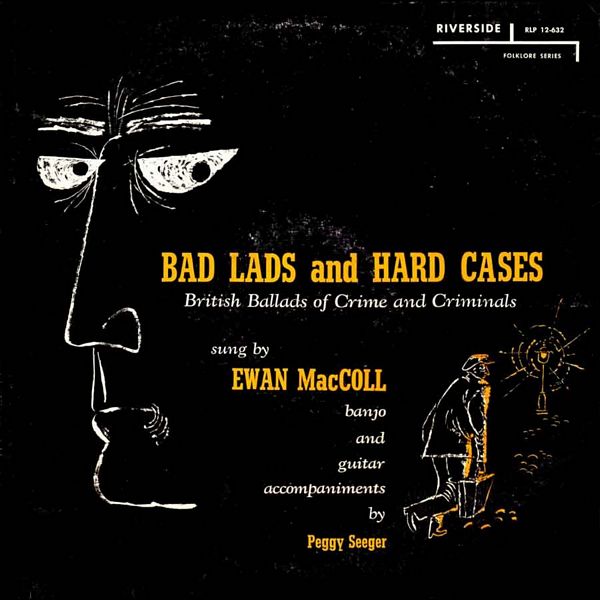

Sleeve Notes

The mammoth sales of tabloid newspapers specializing in the gory and sensational, the popularity of detective novels and 'thrillers', the countless films and TV features dealing with acts of violence, all point to public interest in crime and criminals.

This somewhat morbid fascination with underworld activity is no new phenomenon. A glance through Professor Child's collection of "The English and Scottish Popular Ballads" shows that rather more than one in three of the traditional texts assembled there deal with assorted acts of violence. Theft, treachery, assault, rape, kidnapping, cattle-rustling, piracy, murder in all its forms … there isn't a crime in the police gazette that hasn't been put to music.

The hard core of the real popular heroes of the traditional ballads is that swaggering band of hard-living, hard-riding and hard-fighting outlaws — Johnny Armstrong, Jock o' the Side, Johnny o' Breadislie, Hughie the Graeme — the moss troopers who ranged the debatable lands of the Scots lowland borders and refused to acknowledge the laws and proscriptions of Kings.

These guerillas of the border peasantry inherited the mantle of Robin Hood. Their qualities are the qualities of all the heroes of folk poetry. They were strong, courageous, skillful with weapons, scornful of authority, witty, fair-minded; they were loyal to their friends and just to their enemies, and they could face death with a jest on their lips. Though they were hunted men, they were the living embodiment of the peasantry's concept of freedom, and this at a time when freedom was only a dream.

They were the progenitors of all the 'bad men' heroes of the English-speaking world: of Dick Turpin, Claude Duval, Brennan of the Moor, Jesse James, Sam Bass, Billy the Kid, Bold Jack Donahue and Pretty Boy Floyd.

Where crimes of passion are the themes of traditional ballads, the events move towards the violent climax with all the inevitability of a Greek tragedy. And, as with the characters in the plays of Aeschylus and Sophocles, the protagonists are larger than life, filling the landscape so that there is no room left for irrelevant detail. Here there is no moralizing on the evils of murder. It is sufficient to state the act of violence and the events which led up to it; the rest is silence.

The 'Confession from the Gallows' type of ballad belongs, both in feeling and in structure, with the 'broadsides' which flourished from 1500 to 1800, though confession ballads continued to be made until such time as public executions were discontinued. For the most part the 'broadsides' deserve professor Child's characterization as "veritable dunghills" and yet, here and there, one comes upon flashes of pure feeling. And traditional singers, who always have the last word, have kept a surprisingly large number of them alive.

The element of protest, almost entirely absent in the confession songs, is a distinct feature of the 'Transportation Ballads.' Though these songs are generally cast in the same mold as the confession songs, they display fewer traits of Grubb Street construction and, on the whole, the poetry, though often crude, is not without vigor. As a body they represent the most recent and perhaps the last great impulse towards song-making on the part of the English peasantry.

Prison life in Britain has produced few genuine folk songs. Parodies exist in plenty, but they are generally of an ephemeral nature and rarely outlive a prison sentence. The only British songs which can compare with the convict group songs of U.S. southern prisons and state-farms are those which came out of the late 17th and 18th century treadmills. Several of these are still current with English south country singers. They represent an important part of our prison literature.

The present folksong revival in Britain has made many thousands of young people familiar with these old songs; it has, in addition, produced a growing number of new ballads about crime and criminals, ballads characterized by an understanding of the social causes of crime. In every city between Dundee and London, there may be found groups of young people who sing songs like The Ballad of Bentley and Craig and Go Down You Murderer.

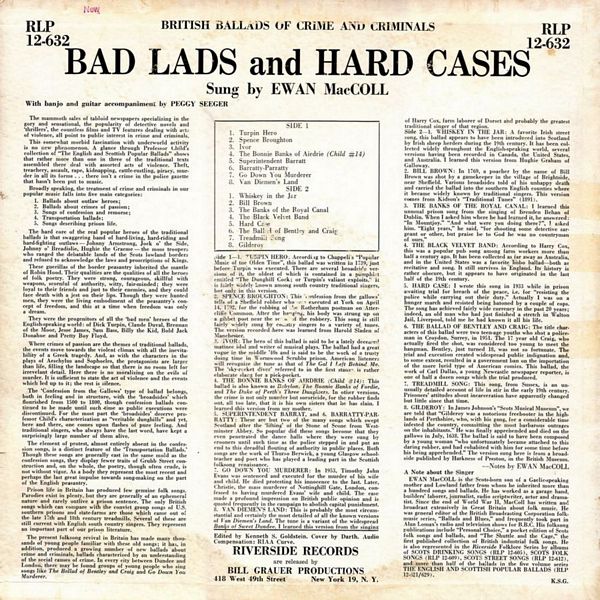

TURPIN HERO —

According to Chappell's ''Popular Music of the Olden Time", this ballad was written in 1739. just before Turpin was executed. There are several broadside versions of it, the oldest of which is contained in a pamphlet entitled "The Dunghill Cock; or Turpin's valiant exploits." it is fairly widely known among south country traditional singers, but only in this version.

SPENCE BROUGHTON —

This confession from the gallows" tells of a Sheffield robber who was executed at York on April 14, 1752, for the robbing of the Rotherham postman on Attercliffe Common. After the hanging. his body was strung up on a gibbet post near the scene of the robbery. This song is still fairly widely sung by country singers to a variety of. runes. The version recorded here was learned from Harold Sladen of Manchester.

IVOR —

The hero of this ballad is said to be a lately deceased matinee idol and writer of musical plays. The ballad had a great vogue in the middle '40s and is said to be the work of a trusty doing time in Wormwood Scrubbs prison. American listeners will recognize the tune as that of The Gal I Left Behind Me. The 'sky-rccket diver' referred to in the first stanza is rather elaborate slang for a pick-pocket.

THE BONNIE BANKS OF AIRDRIE (Child #14) —

This ballad is also known as Babylon, The Bonnie Banks of Fordie, and The Duke of Perth's Three Daughters. In other versions, the crime is not only murder but sororicide. for the robber finds out, all too late, that it is his own sisters that he has slain. I learned this version from my mother.

SUPERINTENDENT BARRAT, and BARRATTY-PARRATTY —

These are but two of the many songs which swept Scotland after the 'lifting' of the Stone of Scone from West-minster Abbey. So popular did these songs become that they even penetrated the dance halls where they were sung by crooners until such time as the police stepped in and put an end to this dreadful flouting of authority in public places. Both songs are the work of Thurso Berwick, a young Glasgow school-teacher and poet who has played a leading part in the Scottish folksong renaissance.

GO DOWN YOU MURDERER —

In 1953. Timothy John Evans was sentenced and executed for the murder of his wife and child. He died protesting his innocence to the last. Later. Christie, the mass murderer of Nottinghill Gate. London, confessed to having murdered Evans' wife and child. The case made a profound impression on British public opinion and is quoted frequently in the campaign to abolish capital punishment.

VAN DIEMEN'S LAND —

This is probably the most circumstantial and certainly the most detailed of all the known versions of Van Diemen's Land. The tune is a variant of the widespread Banks of Sweet Dundee. I learned this version from the singing of Harry Cox, farm laborer of Dorset and probably the greatest traditional singer of that region.

WHISKEY IN THE JAR —

A favorite Irish street song, this ballad appears to have been introduced into Scotland by Irish sheep herders during the 19th century. It has been collected widely throughout the English-speaking world, several versions having been recorded in Canada, the United States, and Australia. I learned this version from Hughie Graham of Galloway.

"BILL BROWN —

In 1769, a poacher by the name of Bill Brown was shot by a gamekeeper in the village of Brightside, near Sheffield. Various broadsides told of his unhappy death and carried the ballad into the southern English counties where it became widely known by traditional singers. This version comes from Kidson's "Traditional Tunes" (1891).

THE BANKS OF THE ROYAL CANAL —

I learned this unusual prison song from the singing of Brenden Behan of Dublin. When I asked him where he had learned it, he answered: "In Mountjoy." "And what were you doing there?", I asked him. "Eight years," he said, "for shooting some detective sar-geant or other, but praise be to God he was no countryman of ours."

THE BLACK VELVET BAND —

According to Harry Cox, this was a popular pub song among farm workers more than half a century ago. It has been collected as far away as Australia, and in the United States was a favorite hobo ballad — both as recitative and song. It still survives in England. Its history is rather obscure, but it appears to have originated in the last half of the 19th century.

HARD CASE —

I wrote this song in 1933 while in prison awaiting trial for breach of the peace, i.e. for "resisting the police while carrying out their duty." Actually I was on a hunger march and resisted being batoned by a couple of cops. The song has achieved fairly wide currency in the past 20 years; indeed, an old man who had just finished a stretch in Walton Jail, Liverpool, told me he had known it all his life.

THE BALLAD OF BENTLEY AND CRAIG —

The title characters of this ballad were two teen-age youths who shot a policeman in Croydon, Surrey, in 1951. The 17 year old Craig, who actually fired the shot, was considered too young to meet the hangman. Bentley, just turned 18, was not so fortunate. The trial and execution created widespread public indignation and. to some extent, resulted in a government ban on the importation of the more lurid type of American comics. This ballad, the work of Carl Dallas, a young Newcastle newspaper reporter, is one of half a dozen songs which the trial produced.

TREADMILL SONG —

This song, from Sussex, is an unusually detailed account of life in stir in the early 19th century. Prisoners' attitudes about incarceration have apparently changed but little since that time.

GILDEROY —

In James Johnson's "Scots Musical Museum", we are told that "Gilderoy was a notorious freebooter in the highlands of Perthshire, who, with his gang, for a considerable time infested the country, committing the most barbarous outrages on the inhabitants." He was finally apprehended and died on the gallows in July, 1638. The ballad is said to have been composed by a young woman "who unfortunately became attached to this daring robber, and had cohabited with him for some time before his being apprehended." The version sung here is from a broadside published by Harkness of Preston, in the British Museum.

— Notes by EWAN MacCOLL

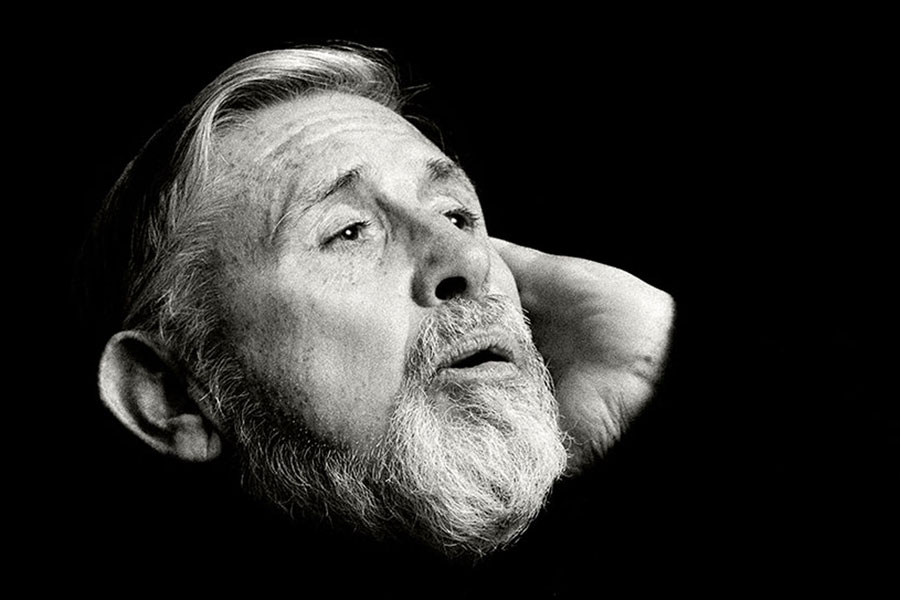

A Note about the Singer

EWAN MacCOLL is the Scots-born son of a Gaelic-speaking mother and Lowland father from whom he inherited more than a hundred songs and ballads. He has worked as a garage hand, builders' laborer, journalist, radio scriptwriter, actor and dramatist. Since the end of World War II. MacColl has written and broadcast extensively in Great Britain about folk music. He was general editor of the British Broadcasting Corporation folk-music series, "Ballads and Blues," and frequently took part in Alan Lomax's radio and television shows for B.B.C. His folksong publications include "Personal Choice," a pocket edition of Scots folk songs and ballads, and "The Shuttle and the Cage," the first published collection of British industrial folk songs.

He is also represented in the Riverside Folklore Series by albums of SCOTS DRINKING SONGS (RLP 12-605), SCOTS FOLK SONG (RLP 12-609), SCOTS STREET SONGS (RLP 12-612), and more than half of the ballads in the five volume series THE ENGLISH AND SCOTTISH POPULAR BALLADS (RLP 12-621/629).