|

|

Sleeve Notes

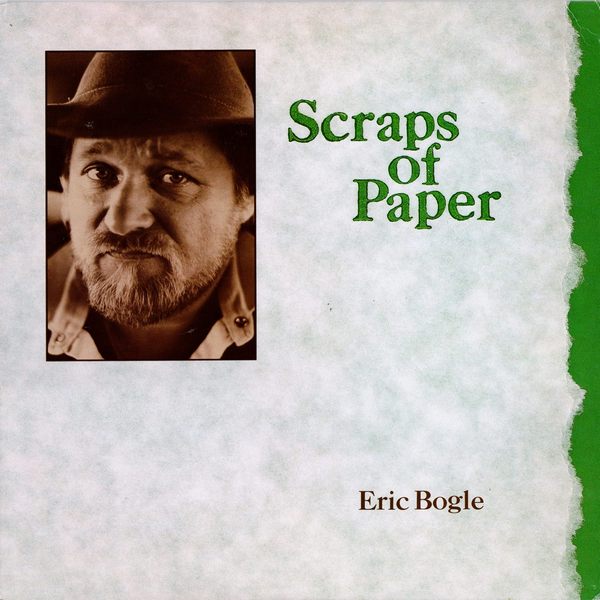

Eric Bogle is a Scot by birth, an Australian by choice, an accountant by training, a musician by profession, and one of the most astounding songwriters in contemporary acoustic music by virtually all accounts. He is modest to a fault ("I'm a wee, short, fat bloke with thinning hair; songwriters, by popular demand, should be six feet two, thin, aesthetic, dark-haired, and moody") and a much better performer than he gives himself credit for. Perhaps most important, however, he has crafted a body of music over the past decade that has redefined social and topical song.

Most Americans — and Britons and Europeans, for that matter — first heard of Eric Bogle when they encountered his masterful condemnation of the carnage at the Battle of Gallipoli in World War I, "And the Band Played 'Waltzing Matilda." The international success of that song, like so many of the milestones in Eric's life, was almost accidental. Eric was a hobbyist songwriter (following an early period of singing traditional folk songs in Scotland on the club circuit, which in turn had followed a tour of duty in a 1960s Top-40 band) who had emigrated to Australia in 1969. In 1972, after watching a parade of frail, elderly veterans of the ill-advised and horribly bloody Gallipoli campaign of 1915 (which had involved, for the most part, troops from Australia and New Zealand, and was such a disaster that Winston Churchill, then a naval official, lost his job over it), Eric wrote "Matilda." He sang it in 1975 at a national songwriting competition in Brisbane; when it came in third, the crowds nearly rioted in protest. Someone who heard it was taken with it who wouldn't be? — and carried it off to Britain, where it would be recorded by June Tabor. Eric Bogle's name finally started to be known.

There have been many other profoundly poetic, almost painfully insightful songs since then, from the chilling "No Man's Land," with its haunting evocation of the youth and hope that are among the first victims of war, to "A Reason for It All," which is to my mind an anthem not only for our times, but for our very humanity and the need to preserve our capacity for caring against most unfavorable odds.

However, as Eric himself is quick to point out, "My mind is not filled only with graveyards, military cemeteries, marches, and old people dying alone. If it was, I'd throw myself off a building! I'm no different from any other thinking human being. I'm concerned about things like that. But I also like a good laugh and a good drink, just like most other people." And, indeed, the world of his songs is also populated by tales of cats that tried to outrun tractor-trailers (resulting in the oddest lament in all of English-language folk music, I suspect), delightfully goofy imitations of Bob Dylan, and odes to such eccentric institutions as the smoke-filled Australian barbecue and the dubious contents of Down Under take-out food.

In the end, Eric Bogle succeeds as a chronicler of our time because of his eye for our foibles and his compassion in the face of our stupidities. Once asked where he found his inspirations, he replied. "There are several billion of them sharing the planet with you." Eric's eye is on the sparrow and the swagman, the subsistence farmer musing as his life comes to a close, the spun-glass relationships on which we pin our hopes. But because he, himself, is possessed of so much hope, even the most tragic of tales becomes uplifting in his hands. "I still feel that I have 'the' song inside me somewhere," he says. "The ultimate song is the one that sums up my philosophy, points toward the future, and gives everyone hope and inspiration. I'm full of anticipation when I think about the songs I still have to write." So, I might add, are the rest of us.

Emily Friedman

Editor, Come for to Sing magazine

June 1983