|

|

|

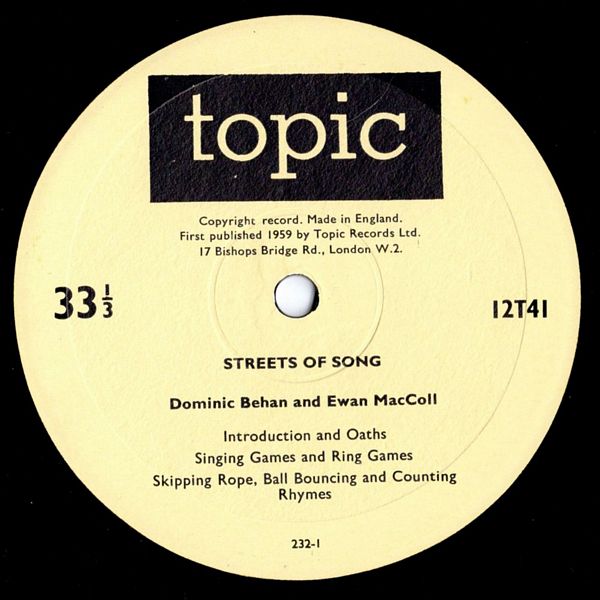

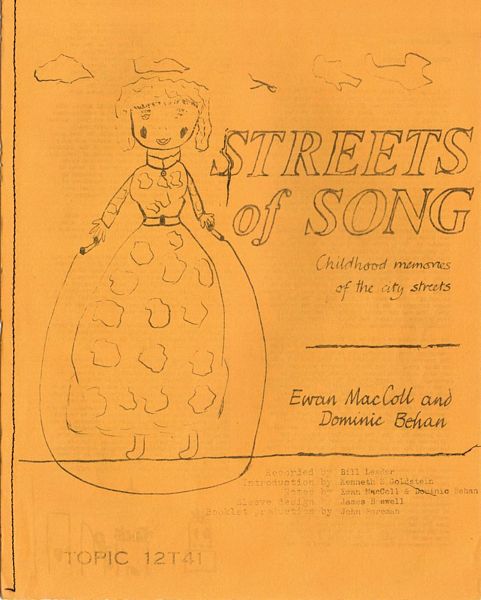

Sleeve Notes

An Introductory Note By Kenneth S. Goldstein

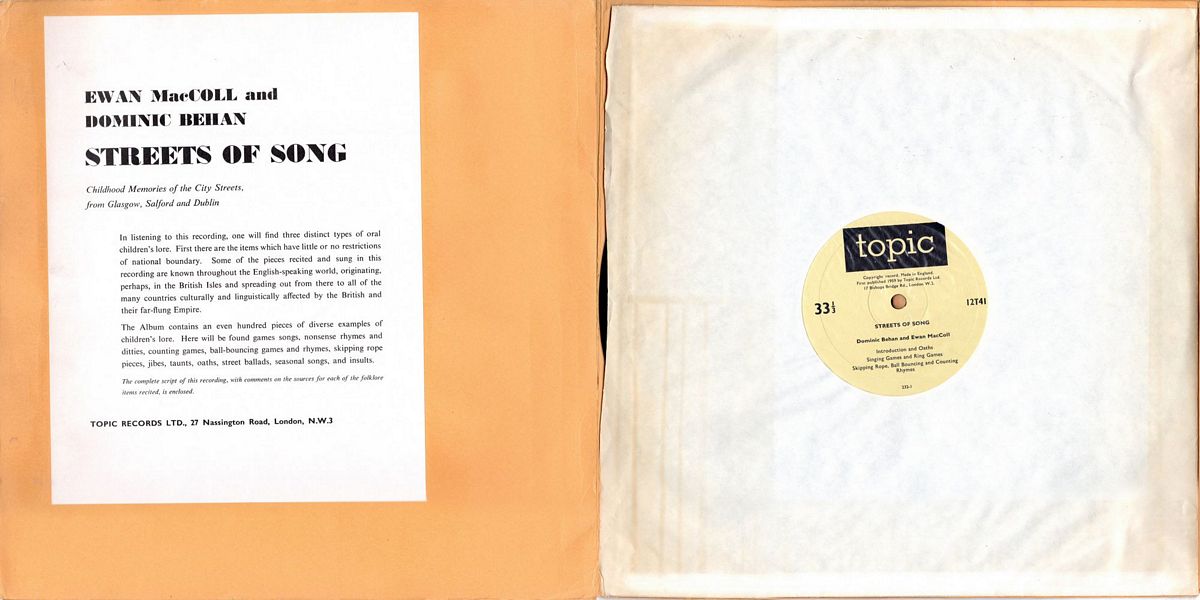

In listening to this recording, one will find three distinct types of oral children's lore. First there are the items which have little or no restrictions of national boundary. Some of the pieces recited and sung in this recording are known throughout the English-speaking world, originating, perhaps, in the British Isles and spreading out from there to all of the many countries culturally and linguistically affected by the British and their far-flung empire. Who, in the English-speaking world, for example, has not heard one or another version of the singing-game The Farmer Wants a Wife (heard in a Dublin Irish version on this recording), or Poor Mary Sat A-Weeping (from Salford on this recording). You may know these pieces by other names, and in forms differing quite radically from those presented on this recording, but it will require little imagination or insight to realise the relationship of the versions you know to those presented here.

A second category of pieces found in this recording are those which appear to have strictly national boundaries, being known either only in the British Isles or, perhaps, only in a single country or national group. Such pieces are frequently related to festivals or events which are purely national in character and incidence, or are so dependent upon purely national events or references as to make them almost meaningless outside of the national boundary of the country in which, they may be found. Such pieces include the holiday song Christmas is Coming (item number 67, from Dublin, but known throughout the British Isles), and the Scottish jibe, Wha saw the tattle howkers (item number 62, from Glasgow, but known in other parts of Scotland) among numerous others.

The third category consists of those pieces of a purely local nature, existing almost exclusively in a single community, town or county, but rarely found elsewhere. The reasons for such limitation of tradition are similar to those given for the second category mentioned above, but with considerably more localised references or language. Such piece include Up The Mucky Mountains (item number 64) and Jessie Stockton (item number 68), both from Salford, and Cheer up, Russell Street (item number 56) from Dublin. Into this last category must also go those pieces which are the creative efforts of a moment, in use for only a short period of time, and fading into the world of lost traditions almost before they were born. Occasionally such-pieces fall into the collector's lap, but the collector (at best, just an accident in time, in such instances) has no way of sorting out these pieces from those which are more than just mere ephemera.

The record contains an even 100 pieces of diverse examples of children's lore. Here will be found game songs, nonsense rhymes and ditties, counting games, ball-bouncing games and rhymes, skipping-rope pieces, jibes, taunts, oaths, street ballads, seasonal songs, and insults. What is the origin of these pieces? For most of them we cannot even begin to speculate on the question of origins.

Some few can be pinpointed to historical occurrences and personages King Henry, King Henry (item number 12), tells of the affairs of love of a well-remembered English monarch. Others are the breakdown of older traditional ballads and tales; I know a woman, she lives in the woods (item number 23), obviously derives from the ballad The Cruel Mother (Child 20). Some like items 4, 56 and 59, are children's parodies of recent creations, including music hall and popular songs. Most of the pieces are created out of happenings and sights of everyday life. Because of the universality of their subject matter they might arise anywhere or at almost any time so it is an impossible task to do much more than guess at their origins.

First, we are introduced to the cultural milieu with which we are dealing. Poverty, a proud working-class inheritance, slum conditions, and the everyday, mundane things and occurrences affecting the individuals concerned. Next, we are presented with the oral products of that environment, set off against a train of thought concerning those products, not of the children living, playing and reciting those pieces of lore, but of two adult bearers of this urban tradition whose sensitivity to the setting is expressed in terms of mature afterthought. The opportunity presented by this recording to study the whys and wherefores of urban childhood traditions is the next best thing to working in the field with the children themselves.

One fascinating problem suggested by working with children's lore, and, even more specifically, with the lore of working-class children, is the question of class boundaries of such lore. Of this question, Dominic Behan has written:

"It can — so far as kids are concerned — be made only by children who own so little other rights to amusement that they must sing and make up songs about themselves and the places they inhabit; tenement house schools, neighbours, and, most and biggest of all, their playground — the streets. Maybe this not quite true, maybe other classes of folks' children make up other classes of songs. All I can say is if they do, I have never heard them."

"So much for the songs: what of the games? Are they 'class' bound? Do they belong to certain people or are they the property of all? Once again, I don't know. Once again I will guess, and say all".

The challenge has been issued. It is the duty of folklorists, sociologists, and psychologists to take it up and answer the question. An attempt to do so from a library chair will prove futile; the data are insufficient and largely undocumented in most of the existing works on children's lore. By utilizing the existing tools of each discipline we can expect to arrive at a satisfactory conclusion. We are fortunate in dealing with children's lore, to be working in an area which appears to have no beginning or end in time, and while some scholars have bemoaned the dying of oral tradition (such claims have been made for the past century, though I for one prefer to think of traditions changing and evolving rather than dying), none will be so rash as to deny the very vital nature of children's songs and games. There is no question of the existence of sufficient material for study.

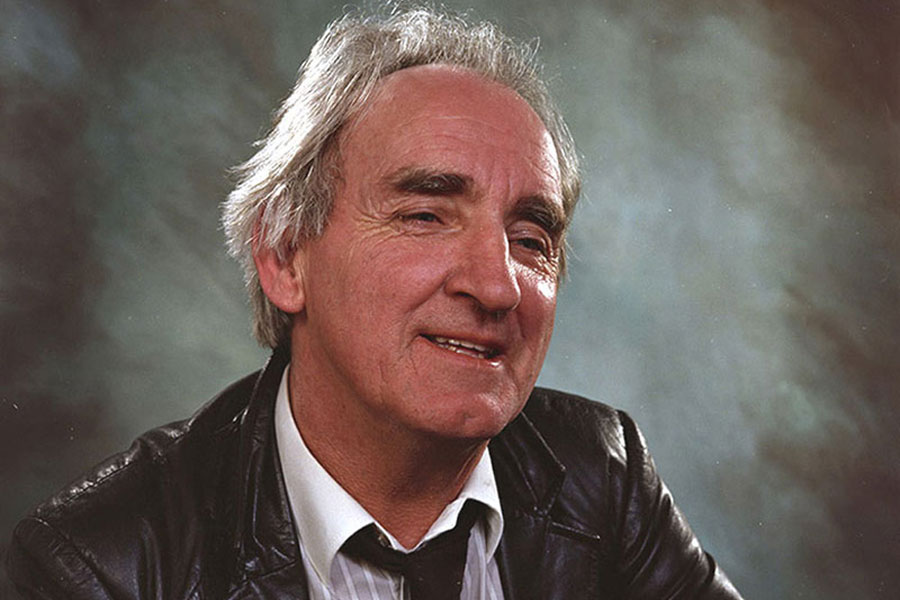

About the Artists

EWAN MacCOLL was born in Auchterarder, Perthshire, Scotland, the son of a Lowland Scots father and a Gaelic-speaking mother. Both parents had an extensive repertoire of Scots folk songs and ballads, and a large part of MacColl's tremendous repertory was learned from them.

Of his early childhood, excellent commentary is given in this recording. After leaving school at the age of 14, he spent the next 10 years working at odd Jobs between periods of unemployment. While working as a street singer, he was picked up by a B.B.C. direct and given his first radio broadcast in a program called Music of the Streets. In 1935, MacColl began to devote an increasing amount of his time in writing programs for the B.B.C., including his first group of Folklore broadcasts. Included among his many folkmusic activities have been the collecting of folksongs for the B.B.C. archives, the production of regular folkmusic concerts, touring concert halls in England Scotland presenting folkmusic at a popular level and performing folksongs on radio broadcasts from every major city in Europe. He has also made numerous recordings of British folk songs available in most parts of the English-speaking world.

In addition to being one of Great Britain's leading folksingers, it should be noted that MacColl is a leading figure in British writing and acting circles. In 1947, George Bernard Shaw was sufficiently inspired by MacColl's work to remark: "Apart from myself, MacColl is the only man of genius writing for the theatre in England today."

MacColl is also the editor of three excellent pocket- size anthologies of folksongs: "Scotland Sings." "Personal Choice", and "The Shuttle and the Cage," the latter being the first general collection of British industrial songs ever published.

DOMINIC BEHAN was born in Dublin, Ireland, having a traditional Irish fiddler as a father and a folksinger as a mother. Born into a family of entensely partisan I.R.A. supporters, it was not surprising that he Joined the Na Fianna h-Eireann (The Republican Boy Scouts) at the age of six and was an active fighter for the I.R.A. at 16. His activities on behalf of his political convictions have resulted in his being imprisoned, in Dublin and in London, four times between 1951 and 1954. Following in the footsteps of his uncle, the noted rebel songwriter Peadar Kearney, he has become one of Ireland's leading political writers, his published works including poetry, rebel ballads, and political articles in leading Irish and British periodicals.