|

|

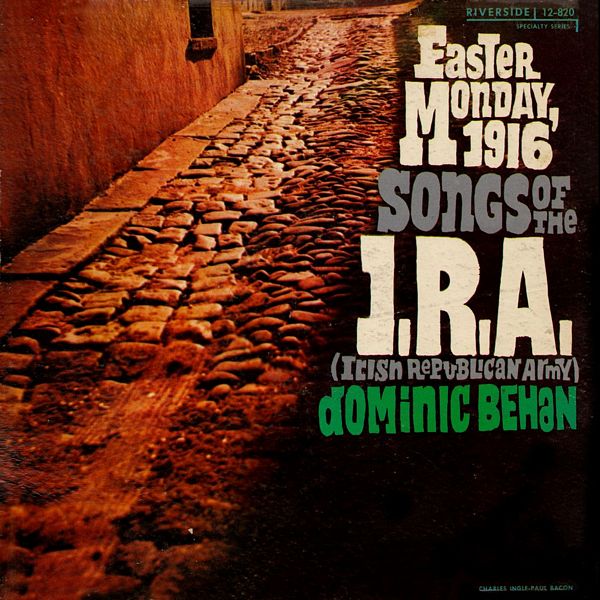

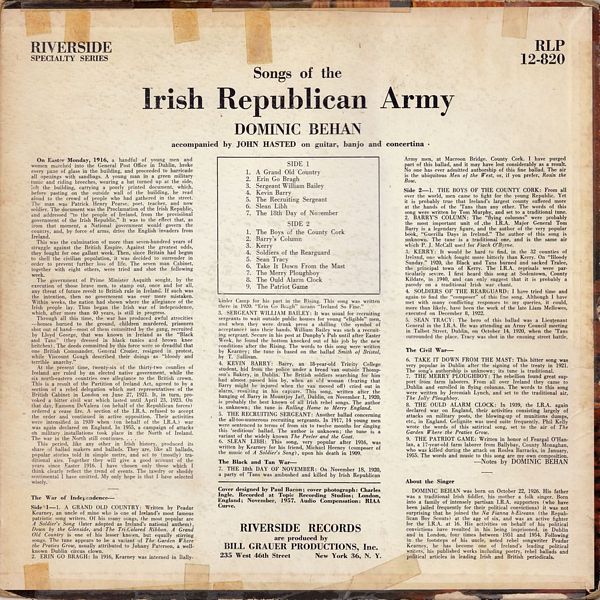

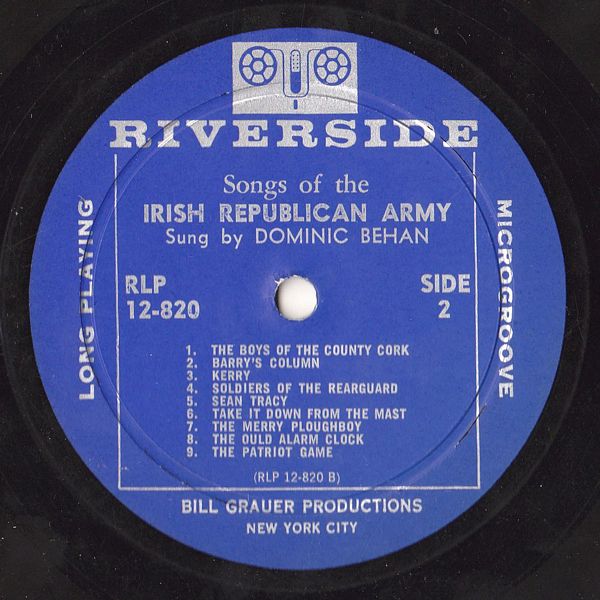

Sleeve Notes

On Easter Monday, 1916, a handful of young men and women marched into the General Post Office in Dublin, broke every pane of glass in the building, and proceeded to barricade all openings with sandbags. A young man in a green military tunic and riding breeches, wearing a hat turned up at the side, left the building, carrying a poorly printed document, which, before pasting on the outside wall of the building, he read aloud to the crowd of people who had gathered in the street. The man was Patrick Henry Pearse, poet, teacher, and now soldier. The document was the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, and addressed "to the people of Ireland, from the provisional government of the Irish Republic." It was to the effect that, as from that moment, a National government would govern the country, and, by force of arms, drive the English invaders from Ireland.

This was the culmination of more than seven-hundred years of struggle against the British Empire. Against the greatest odds, they fought for one gallant week. Then, since Britain had begun to shell the civilian population, it was decided to surrender in order to prevent further loss of life. The seven man Cabinet, together with eight others, were tried and shot the following week.

The government of Prime Minister Asquith sought, by the execution of those brave men, to stamp out, once and for all, any threat of future revolt to British rule in Ireland. If such was the intention, then no government was ever more mistaken. Within weeks, the nation had shown where the allegiance of the Irish people lay. Thus began the Irish war of independence, which, after more than 40 years, is still in progress.

Through all this time, the war has produced awful atrocities — homes burned to the ground, children murdered, prisoners shot out of hand — most of them committedby the gang, recruited by Lloyd George, that was known in Ireland as the "Black and Tans" (they dressed in black tunics and brown knee britches). The deeds committedby this force were so dreadful that one British Commander, General Crozier, resigned in protest, while Viscount Gough described their doings as "bloody and terrible anarchy."

At the present time, twenty-six of the thirty-two counties of Ireland are ruled by an elected native government, while the six north-eastern countries owe allegiance to the British crown. This a result of the Partition of Ireland Act, agreed to by a section of a rebel delegation which met representatives of the British Cabinet in London on June 27, 1921. It, in turn, provoked a bitter civil war which lasted until April 23, 1923. On that day, Eamonn DeValera (on behalf of the Republican forces) ordered a cease fire. A section of the I.R.A. refused to accept the order and continued in active opposition. Their activities were intensified in 1939 when (on behalf of the I.R.A.) war was again declared on England. In 1955, a campaign of attacks on military installations took place in the North of Ireland. The war in the North still continues…

This period, like any other in Irish history, produced its share of ballad makers and ballads. They are, like all ballads, popular stories told in simple metre, and set to (mostly) traditional airs. Together they will give a good account of the years since Easter 1916. I have chosen only those which I think clearly reflect the trend of events. The tawdry or shoddy sentimental I have omitted. My only hope is that I have selected wisely.

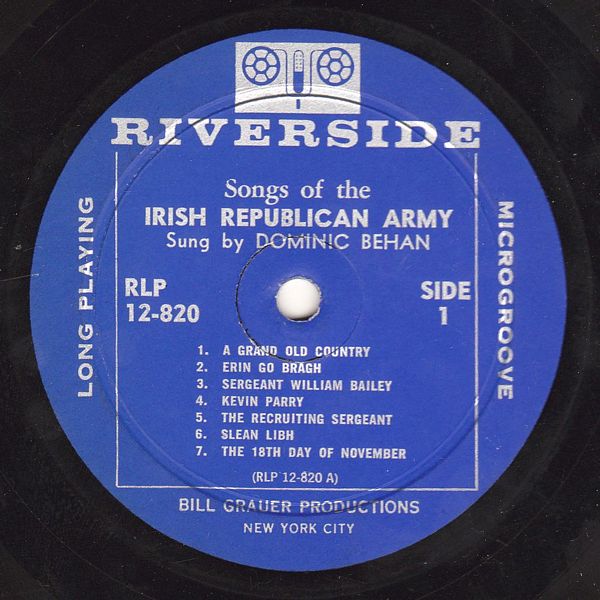

The War of Independence —

A GRAND OLD COUNTRY: Written by Peadar Kearney, an uncle of mine who is one of Ireland's most famous patriotic song writers. Of his many songs, the most popular are A Soldier's Song (later adopted as Ireland's national anthem), Down by the Glenside, and The Tri-Colored Ribbon. A Grand Old Country is one of his lesser known, but equally stirring songs. The tune appears to be a variant of The Garden Where the Praties Grow, usually attributed to Johnny Paterson, a well-known Dublin circus clown.

ERIN GO BRAGH: In 1916, Kearney was interned in Ballykinler Camp for his part in the Rising. This song was written there in 1920. "Erin Go Bragh" means "Ireland So Fine."

SERGEANT WILLIAM BAILEY: It was usual for recruiting sergeants to wait outside public houses for young "eligible" men, and when they were drunk press a shilling (the symbol of acceptance) into their hands. William Bailey was such a recruiting sergeant. Secure in his post at Dunphy's Pub until after Easter Week, he found the bottom knocked out of his job by the new conditions after the Rising. The words to this song were written by Kearney; the tune is based on the ballad Smith of Bristol, by T. Sullivan.

KEVIN BARRY: Barry, an 18-year-old Trinity College student, hid from the police under a bread van outside Thompson's Bakery, in Dublin. The British soldiers searching for him had almost passed him by, when an old woman (fearing that Barry might be injured when the van moved off) cried out in alarm, resulting in his capture. This song, written after the hanging of Barry in Mountjoy Jail, Dublin, on November 1, 1920, is probably the best known of all Irish rebel songs. The author is unknown; the tune is Rolling Home to Merry England.

THE RECRUITING SERGEANT: Another ballad concerning the all-too-numerous recruiting sergeants. In 1917, 14 young men were sentenced to terms of from six to twelve months for singing this 'seditious' ballad. The author is unknown; the tune is a variant of the widely known The Peeler and the Goat.

SLEAN LIBH: This song, very popular after 1916, was written by Kearney for his friend, Michael Heeney (composer of the music of A Soldier's Song), upon his death in 1909.

THE 18th DAY OF NOVEMBER: On November 18, 1920, a party of 'Tans' was ambushed and killed by Irish Republican Army men, at Macroon Bridge. County Cork. I have purged part of this ballad, and it may have lost considerably as a result. No one has ever admitted authorship of this fine ballad. The air is the ubiquitous Men of the West, or, if you prefer, Rosin the Bow.

The Black and Tan War —

THE BOYS OF THE COUNTY CORK: From all over the world, men came to fight for the young Republic. Yet it is probably true that Ireland's largest county suffered more at the hands of the 'Tans than any other. The words of this song were written by Tom Murphy, and set to a traditional tune.

BARRY'S COLUMN: The "flying columns" were probably the most important unit of .the I.R.A. Major General Tom Barry is a legendary figure, and the author of the very popular book, "Guerilla Days in Ireland." The author of this song is unknown. The tune is a traditional one, and is the same air which P. J. McCall used for Fiach O'Byrne.

KERRY: It would be hard to find, in the 32 counties of Ireland, one which fought more bitterly than Kerry. On "Bloody Sunday," 1920, the Black and Tans burned and sacked Tralee, the principal town of Kerry. The I.R.A. reprisals were particularly severe. I first heard this song at Sodentown, County Kildare, in 1940, and can only suggest that it is probably a parody on a traditional Irish war chant.

SOLDIERS OF THE REARGUARD: I have tried time and again to find the "composer" of this fine song. Although I have met with many conflicting responses to my queries, it could, more than likely, have been the work of the late Liam Mellowes, executed on December 8, 1922.

SEÁN TRACY: The hero of this ballad was a Lieutenant General in the I.R.A. He was attending an Army Council meeting in Talbot Street, Dublin, on October 14, 1920, when the 'Tans surrounded the place. Tracy was shot in the ensuing street battle.

The Civil War —

TAKE IT DOWN FROM THE MAST: This bitter song was very popular in Dublin after the signing of the treaty in 1921. The song's authorship is unknown; its tune is traditional.

THE MERRY PLOUGHBOY: The rebellion found great sup-port from farm laborers. From all over Ireland they came to Dublin and enrolled in flying columns. The words to this song were written by Jeremiah Lynch, and set to the traditional air, The Jolly Ploughboy.

THE OULD ALARM CLOCK: In 1939, the I.R.A. again declared war on England, their activities consisting largely of attacks on military posts, the blowing-up of munitions dumps, etc., in England. Gelignite was used suite frequently. Phil Kelly wrote the words of this satirical song, set to the air of The Garden Where the Praties Grow.

THE PATRIOT GAME: Written in honor of Feargal O'Hanlan, a 17-year-old farm laborer from Ballybay, County Monaghan, who was killed during the attack on Roslea Barracks, in January, 1955. The words and music to this song are my own composition.

— Notes by DOMINIC BEHAN

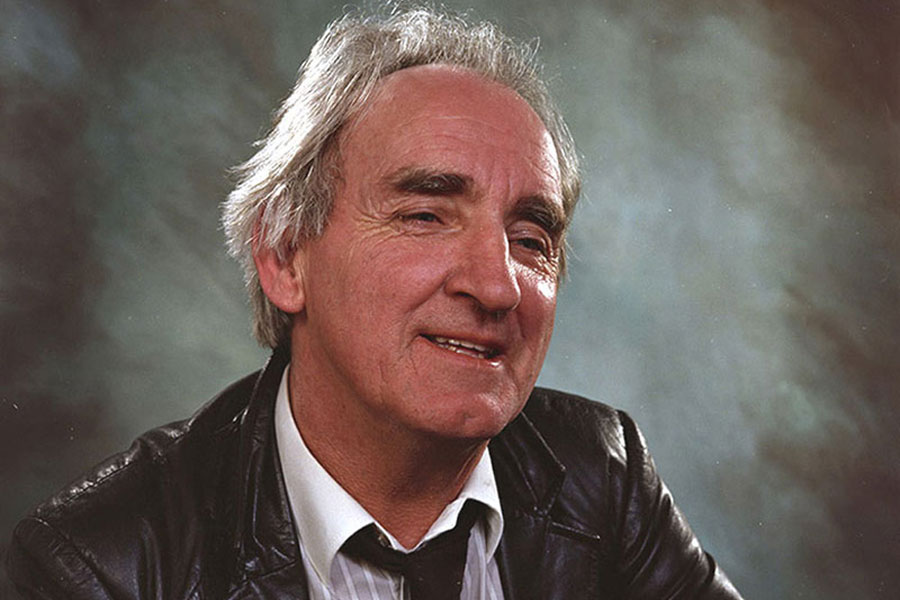

About the Singer

DOMINIC BEHAN was born on October 22, 1926. His father was a traditional Irish fiddler, his mother a folk singer. Born into a family of intensely partisan I.R.A. supporters (who have been jailed frequently for their political convictions) it was not surprising that he joined the Na Fianna h-Eireann (the Republican Boy Scouts) at the age of six, and was an active fighter for the I.R.A. at 16. His activities on behalf of his political convictions have resulted in his being imprisoned, in Dublin and in London, four times between 1951 and 1954. Following in the footsteps of his uncle, noted rebel songwriter Peadar Kearney, he has become one of Ireland's leading political writers, his published works including poetry, rebel ballads and political articles in leading Irish and British periodicals.