|

|

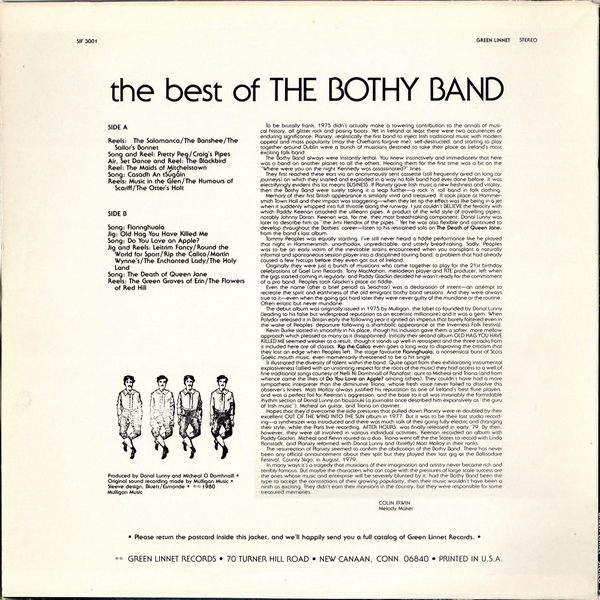

Sleeve Notes

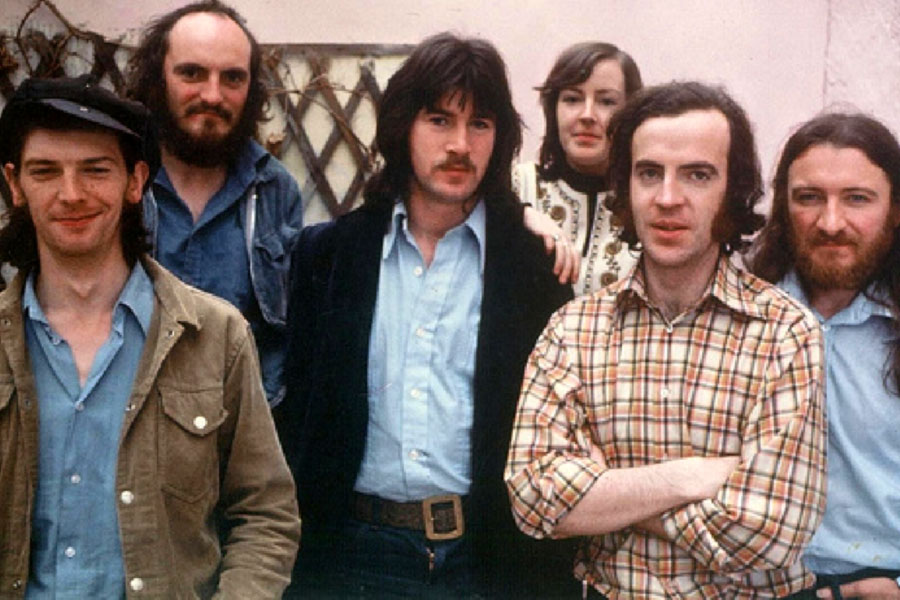

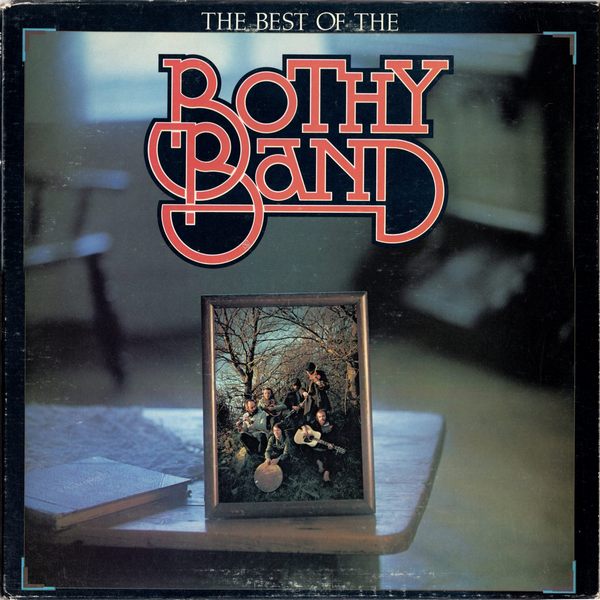

To be brutally frank, 1975 didn't actually make a towering contribution to the annals of musical history, all glitter rock and posing boots. Yet in Ireland at least there were two occurrences of enduring significance: Planxty, realistically the first band to inject Irish traditional music with modern appeal and mass popularity (may the Chieftains forgive me), self-destructed; and starting to play together around Dublin were a bunch of musicians destined to take their place as Ireland's most exciting folk band.

The Bothy Band always were instantly lethal. You knew instinctively and immediately that here was a band on another planet to all the others. Hearing them for the first time was a bit on the "Where were you on the night Kennedy was assassinated?" lines.

They first reached these ears via an anonymously sent cassette (still frequently aired on long car journeys) on which they snarled and exploded in a way no folk band had ever done before. It was electrifyingly evident this lot meant BUSINESS. If Planxty gave Irish music a new freshness and vitality, then the Bothy Band were surely taking it a leap further — a rock n' roll bond in folk clothing.

Memory of their first British appearance is similarly vivid and treasured. It took place at Hammersmith Town Hall and their impact was staggering — when they let rip the effect was like being in a jet when it suddenly whipped into full throttle along the runway. I just couldn't BELIEVE the ferocity with which Paddy Keenan attacked the uilleann pipes. A product of the wild style of travelling pipers, notably Johnny Doran, Keenan was, for me, their most breathtaking component: Dónal Lunny was later to describe him as "the Jimi Hendrix of the pipes." Yet he was also flexible and continued to develop throughout the Bothies' career — listen to his restrained solo on "The Death of Queen Jane", from the bands last album.

Tommy Peoples was equally startling. I've still never heard a fiddle performance like he played that night in Hammersmith: unorthodox, unpredictable, and utterly breathtaking. Sadly, Peoples was to be an early victim of the inevitable strains encountered when you transplant a naturally informal and spontaneous session player into a disciplined touring band, a problem that had already caused a few hiccups before they even got out of Ireland.

Originally they were just a bunch of musicians who come together to play for the 21st birthday celebrations of Gael Linn Records. Tony MacMahon, melodeon player and RTÉ producer left when the gigs started coming in regularly, and Paddy Glackin decided he wasn't ready for the commitment of a pro band. Peoples took Glackin's place on fiddle.

Even the name (after a brief period as Seachtar) was a declaration of intent — an attempt to recreate the spirit and earthiness of the old emigrant bothy band sessions. And they were always true to it — even when the going got hard later they were never guilty of the mundane or the routine. Often erratic but never mundane.

The debut album was originally issued in 1975 by Mulligan, the label co-founded by Dónal Lunny (leading to his false but widespread reputation as an eccentric millionaire) and it was a gem. When Polydor released it in Britain early the following year it ignited on impetus that barely faltered even in the wake of Peoples' departure following a shambolic appearance at the Inverness Folk Festival

Kevin Burke slotted in smoothly in his place, though his inclusion gave them a softer more mellow approach which pleased as many as it disappointed. Initially their second album OLD HAG YOU HAVE KILLED ME seemed weaker as a result, though it stands up well in retrospect and the three tracks from it included here are all classics. "Rip the Calico" even goes a long way to disproving the criticism that they lost an edge when Peoples left. The stage favourite "Fionnghuala", a nonsensical burst of Scots Gaelic mouth music, even momentarily threatened to be a hit single.

It illustrated the diversity of talent within the band. Quite apart from their exhilarating instrumental explosiveness (allied with an unstinting respect for the roots of the music) they had access to a well of fine traditional songs courtesy of Nelli Ni Domhnaill of Ranafast, aunt to Mícheál and Tríona (and from whence came the likes of "Do You Love on Apple?" among others). They couldn't have had a more sympathetic interpreter than the diminutive Tríona, whose fresh voice never foiled to dissolve this observer's knees. Matt Molloy always justified his reputation as one of Ireland's best flute players and was a perfect foil for Keenan's aggression; and the base to it all was invariably the formidable rhythm section of Dónal Lunny on bouzouki (a journalist once described him expansively as "the guru of Irish music"), Mícheál on guitar, and Tríona on clavinet.

Hopes that they'd overcome the side pressures that pulled down Planxty were re-doubled by their excellent OUT OF THE WIND INTO THE SUN album in 1977. But it was to be their last studio recording — a synthesizer was introduced and there was much talk of their going fully electric and changing their style, while the Paris live recording, AFTER HOURS, was finally released in early 79. By then, however, they were all involved in various individual activities: Keenan recorded on album with Paddy Glackin, Mícheál and Kevin toured as a duo, Tríona went off the the States to record with Linda Ronstadt, and Planxty reformed with Dónal Lunny and (briefly) Matt Molloy in their ranks.

The resurrection of Planxty seemed to confirm the abdication of the Bothy Band. There has never been any official announcement about their split but they played their last gig at the Ballisodare Festival, County Sligo, in August, 1979.

In many ways it's a tragedy that musicians of their imagination and artistry never became rich and terribly famous. But maybe the characters who can cope with the pressures of large scale success are the ones whose music and enterprise will be severely blunted by it; had the Bothy Band been the type to accept the constrictions of their growing popularity, then their music wouldn't have been a ninth as exciting. They didn't earn their mansions in the country, but they were responsible for some treasured memories.

COLIN IRWIN

Melody Maker