|

|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

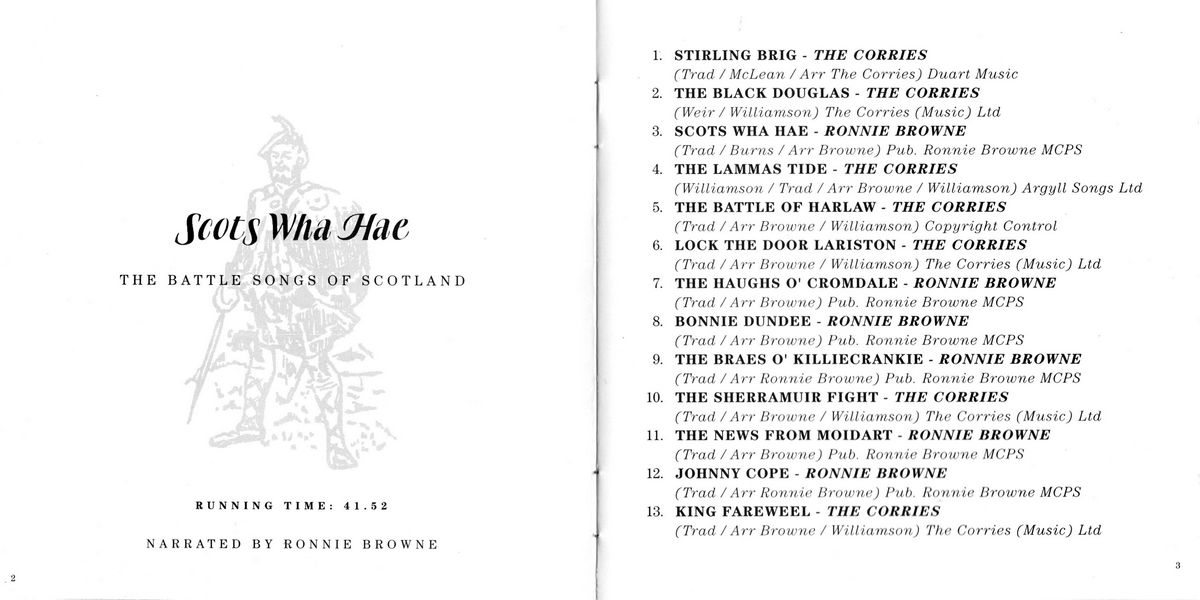

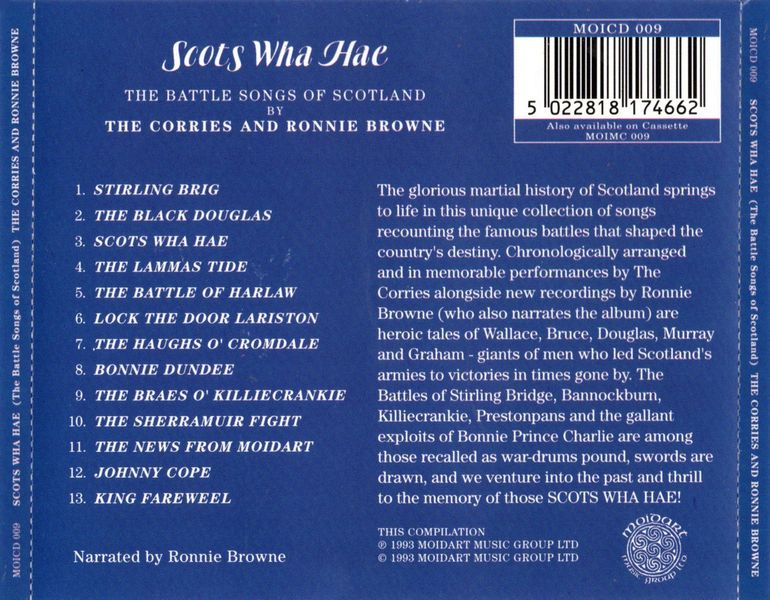

STIRLING BRIDGE — Here in 1297 Sir William Wallace and Andrew Murray took revenge on the English King Edward I, The Hammer of the Scots, whose earlier victories at Berwick, Dunbar, Roxburgh, Edinburgh and Stirling had resulted in the Scottish King John Balliol and The Stone of Destiny being transported to London.

Commanding a vastly outnumbered Scottish army, Wallace and Murray waited until many of the English had crossed the narrow Bridge of Stirling then struck, cutting the enemy into two halves and slaughtering those who had crossed whilst the remainder could only helplessly watch. Soon the rout was completed with the remainder of the English army chased all the way back over the Border. A great morale boosting victory for the Scots who until then appeared to be defeated — if not conquered.

THE BLACK DOUGLAS — In the long struggle during the early 14th century for Scottish independence the exploits of Sir James Douglas became legendary. His deep penetrative raids into northern England bought something of the terror and devastation so often unleashed in Scotland by invaders from the South. He fought in most major battles of his time, including Bannockburn, however it is as a guerrilla leader he is best remembered as he drained the English of courage, castle and treasure. The sudden rush, the furious onslaught and the chilling war-cry that brought fear into the Border night — A Douglas! A Douglas! A Douglas! The Good Sir James to the Scots but he was known as The Black Douglas to their enemy.

SCOTS WHA HAE — Bannockburn, June 23rd 1314; a place and date embedded deep in Scottish consciousness. Robert the Bruce had gathered five thousand brave Scots, they faced an advancing English army of more than fifteen thousand who were better trained and better equipped. The English King Edward II was confident whilst the Scots were simply determined — they had not been conscripted and recruited as had their English counterparts — they were on the field voluntarily to fight for Scotland and The Bruce.

As the glittering array of the English approached, Bruce addressed his army, inviting any man not prepared to remain on the field and share victory or death as he was, to honourably leave now. Not a man moved — then the Scots rallied and prepared to meet their old foe once again.

It was a two day affair; the first, one of skirmishes and sizing up — the second, a long drawn day of slaughter that began at dawn with a hail of English arrows signalling battle had commenced in earnest. Spiked traps and pits bogged down the heavy English cavalry who were then overpowered — razor sharp Scottish spears pricked and pushed the English into an ever tightening mass — lethal English arrows rained upon the Scots with devastating effect — there were many gallant deaths on both sides — the grim day wore on and the outcome was set to go either way as both armies began to tire.

The seeming deadlock was broken by the arrival of unarmed Scots camp followers who, believing at one point the Scots had won, charged onto the battlefield. The arrival of this host, whom the English believed to be genuine reinforcements, turned the tide and the English panicked then fled — victory went to the near exhausted Scots in one of the most memorable and important battles in the country's history. The song requires no introduction or comment.

THE LAMMAS TIDE — A bold challenge between the two bold knights in the year 1388 created the story behind this fine song. The Scottish Earl of Douglas, proving as adept a guerrilla raider as had The Good Sir Douglas before him, laid desultory siege to Newcastle following a plundering raid into northern England. The town's defendant was Sir Henry Percy, a proud English knight known as 'Hotspur' due to his bold impetuosity, but a gallant man nonetheless.

In a skirmish before the walls of the town Douglas and Percy clashed and Douglas made off with Percy's standard, jeering that he would hang it from the walls of Dalkeith Castle back in Scotland. Annoyed, and realising he outnumbered the Scots three to one, Percy sallied out of Newcastle to pursue the leisurely withdrawal of the Scots.

On the night of August 5th, on the cold and sodden moorland of Otterburn, Hotspur's array poured into the Scots' encampment. In the carnage of the ensuing melee Douglas and Hotspur fought face to face — when they separated Douglas was struck by three spears and fell mortally wounded. The Earl called upon his nephew, Sir Hugh Montgomery, to rally his followers and the cry 'Douglas!' roared out as the Scots broke the English and secured victory. Percy surrendered to Montgomery but it was the courage of the now dead Douglas that won the field.

THE BATTLE OF HARLAW — Not all prominent battles in Scotland were against the English, land was a major cause of dispute and when the land was an entire Earldom and one of the claimants a Stewart, the other the Lord of the Isles, the bloodshed could attain a degree of ferocity verging on madness.

In May 1402 The Earl of Ross died leaving his daughter, Euphemia, as heiress. Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany and Guardian of the Realm, assumed the wardship of Euphemia — styling himself 'Lord of the Ward of Ross'. This angered Donald of the Isles who had a claim to the Earldom through his wife, sister of the late Earl. Eventual confrontation was inevitable.

In 1411 Donald gathered ten thousand of his fighting men. They came in their galleys to Glen More and surged eastward, swallowing Dingwall and capturing Inverness. From here Donald headed southeast either to lay definite claim to the lands of Ross or perhaps he intended to sack Aberdeen. The local lords guessed the latter and the behaviour of the Islesmen as they rampaged onward stiffened the opposition.

Alexander Stewart, Earl of Mar, quickly raised an army from surrounding areas to meet them. At the township of Harlaw where the River Urie is overlooked by the Mither Tap of Bennachie there were a thousand men awaiting when Donald's might arrived.

A day long bloody battle ensued and when night descended upon the carnage there were nine hundred Highland and six hundred Lowland dead. Recoiling westward, Donald claimed victory but the land of Ross was given to the son of Albany and the field of Red Harlaw long remembered in the North.

LOCK THE DOOR LARISTON — Bannockburn had not ended the war of independence though it had marked a turning point that led to the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320 and the Treaty of Edinburgh in 1328. This treaty stated, categorically, that Scotland was a free and independent nation. There followed centuries of unrest on the borders, minor raiding punctuated by full scale war which set the land aflame from Lothian to the Tyne as the English again sought to claim Scotland for their own.

This continuous martial activity led to a new breed of men being reared upon both sides of the frontier, men who lived by the lance and their wits, who fought when necessary and ran when the odds were too great. Men who reived cattle for fun and profit whilst holding crown and country in contempt. In return, kings and governments in Scotland and England exploited these men cynically, using the Borderland as a buffer and the Borderers as a first line of defence.

Certain areas were notorious for the unruly quality of the inhabitants, Bewcastle was an example, the most consistently lawless however, lay just within the Scottish border, a shallow entrance narrowing to a deep gouge between the long border hills — this was Liddesdale.

Here dwelt some of the wildest men in all Scotland, untameable horsemen who raided incessantly and scorned any authority but that of their chiefs … these were the Armstrongs, the Nixons, the Crosiers and, with their base at Lariston, the Elliots, whose proud boast was 'Wha daur meddle wi' me'. Liddesdale was so wild that it was not unknown for Scottish kings to allow the English to raid here unchecked; occasionally the English needed no invitation and attacked in force — they were not always successful as this fine song illustrates.

THE HAUGHS O' CROMDALE — The centuries of warfare between Scotland and England ended with the Union of the Crowns in 1603 as anyone bom thereafter held common citizenship. This did not put an end to the fighting, religious and dynastic disagreements still ensured the march and countermarch of factional armies.

Civil war in England during the 1640's between King Charles and Oliver Cromwell left the Crown reeling and only in Scotland was there hope for the Royalists. James Graham, Marquis of Montrose, was ordered to win Scotland for the King so with the shearing broadswords of MacDonald and Cameron, McLeod, Stewart and, Co. Antrim MacDonells, Montrose slashed a bloody path through the Highlands. At Tibbermore in 1644, where seven thousand Covenanters opposed them in the name of Jesus, the clans left a swathe of two thousand bodies all the way to Perth — a distance of some seven miles. Aberdeen was next, where the sack of the city turned into a bloody act of pillage. Other victories followed and a legend wove itself around the name of Montrose so when bad times fell upon a future Stuart king, the memory could be recalled, the victories transported.

Forty years after Montrose had been hanged, the, Jacobite clans, in the last remnants of the uprising started by Viscount Dundee before his death at Killiecrankie, were surprised and dispersed in the mist at Cromdale on the River Spey. In due course a song was written to commemorate the event but an anonymous Jacobite songster resurrected Montrose in a rematch of the battle. Montrose, needless to say, reunited the clans — and won.

BONNIE DUNDEE — During the late 17th century in Scotland there came to prominence a man named John Graham of Claverhouse — Covenanters named him Bluidy Claver'se. In contrast, the same man was known as Bonnie Dundee, darling of the Stuarts, a dashing cavalier who had the ear of the new King James II, brother of Charles.

James was as ardent a Catholic as his rival for the crown, William of Orange, was Protestant. When William swept to the throne through his Stuart wife, Mary, and the Revolution men called Glorious, the Scots were slow to welcome him despite his religion. Three regiments of mercenary Scots soldiers backed by a swarm of Covenanters marching upon Edinburgh, helped confirm Scottish delight at the accession of their new king (who was never to set foot in their country) and only men like the newly created Viscount Dundee remained loyal to James II — who had by now fled to France.

Proving he possessed a lot more mettle than did his monarch, Dundee brought fifty horse into the Capital to challenge the Williamites when the Convention of Estates was summoned in Scotland by order of King William. His gallant few however could do nothing when a Williamite Whig was elected as President. As the Stuarts withdrew from Parliament House, Dundee led his riders out of Edinburgh in a ranting, rollicking rout that created consternation among the dour citizens. History was perhaps justifiably unkind to Bluidy Claver'se but it had reserved a very special niche for Bonnie Dundee as he rode north to meet his destiny.

THE BRAES O' KILLIECRANKIE — Dundee's position in 1689 was similar to that of Montrose in 1644, with the enemies of his king controlling the Lowlands, and the Highlands a confusion of quarrelling clans. Only if the clans were united could they fight for King James and now Dundee revealed the genius which had long hidden beneath his sobriquet of Bluidy Claver'se. As charismatic as Montrose, Dundee bribed the Keppoch MacDonalds to join him and arranged a rendezvous at Dalcomera.

The fierce Lochiel, who had once bitten the throat from a Cromwellian officer, brought his Camerons. The MacLeans of Mull arrived, a few hundred Irishmen sent by King James, MacGregors from Balquhidder, Grants from the Northeast and Clan Donald all came in force. A rising was imminent.

Fully aware of the threat posed by Dundee's two thousand, the Estates sent General Hugh Mackay, a professional soldier and a Highlander who had spent most of his career in Dutch service. With him marched eight foot regiments, mostly Lowland Scots, plus a well-armed regiment of dragoons.

Mackay marched to Perth then northward to Jacobite held Blair Castle. To reach their intended destination, he had first to negotiate the deep Pass of Killiecrankie where on the northern exit awaited Dundee. The Jacobites were three hundred feet above Mackay's men and there they waited as the July sun glittered upon the broadswords and claymores. All the long afternoon the clans played their war pipes and yelled their slogans, howling to unnerve the Lowlanders and when the sun finally dipped — Dundee brought them down.

It was a charge in the fashion of Montrose's Highlanders with the clans forming wedges as they bounded screaming towards the enemy, plaids discarded, swords and targes held high they descended as the musketry whittled at their numbers. The redcoats were busy, loading and firing for their lives as the clans drew nearer, then, with only a few yards separating the armies, the Highlanders replied with a single volley before discarding their firearms and hurling themselves upon the triple ranks of the enemy.

The Williamite casualties were horrendous in the carnage that followed — two thousand of Mackay's men were brutally killed but among the six hundred Jacobite dead was the irreplaceable Bonnie Dundee — his death a hammer blow to future Stuart hopes.

Without their gallant leader the clans lost their impetus. At Dunkeld they met the dour Cameronians and after a long day of desperate defence, the psalms of the Cameronians rose triumphant amidst the smoke of the burning town. It only remained for the Jacobite clans to be surprised and scattered in a skirmish at Cromdale for the rising to be defeated.

THE SHERRAMUIR FIGHT — When Queen Anne died in 1714 support for the return of a Stuart king was at its strongest but it was the German King George who mounted the throne. At this time there was an unfortunate lack of leadership amongst the Scottish Jacobites and it was the Earl of Mar who became the mainstay of the Stuart cause. Mar had gained the nickname 'Bobbing John' due to his aptitude for changing sides but now he called together the Highland chiefs who opposed King George and the Union. On September 6th 1715 Mar raised the Stuart standard on the Braes of Mar and proclaimed the eighth James as King. Another chapter in the saga of The Old Pretender was about to begin.

After frustrating his army by months of waiting, Mar decided to act. Hoping to ford the Forth he marched south when Argyll advanced to meet him, occupying Dunblane and positioning his redcoats between the town and Sheffifmuir. It was here the armies met — The Earl of Mar with eight thousand men, The Duke of Argyll with three thousand and both sides containing around a thousand horse.

The battle that followed on the 13th November was one of the strangest ever fought in Scotland. Under Mar's rather inept generalship the Jacobites moved too slowly to take the high ground but during pre-battle manoeuvring the left flank of Argyll's army was also slow, with supporting dragoons badly positioned making the infantry vulnerable. General Gordon of Auchintoul who commanded the Jacobite right was a veteran of the Russian army and he grasped this opportunity to attack at once.

It was a classic Highland charge which endured only one redcoat volley before crunching into the veteran battalions. Neither the new ring bayonets nor the reputation gained in bloody European warfare under Marlborough helped the regulars who crumpled beneath the broadswords, recoiled into the hapless dragoons — and ran.

The Jacobite left presented a total contrast — here the charge had met with steady volleys from the regulars aided by a flank attack from Argyll's cavalry. Forced to withdraw, the Highlanders soon found their backs were to the Allan Water and here most of the Jacobite casualties occurred.

With the right wing of both armies victorious, both commanders withdrew and claimed overall victory — a draw seemed a more appropriate result in this confused battle of the 1715 Stuart campaign, a campaign that in the space of the following twelve months would drift into ignominy through the ineptitude of its leaders — including King James himself.

THE NEWS FROM MOIDART — Between the failure of the Fifteen and the tragic glory of the Forty Five stretched thirty busy years. There were changes in the Highlands where clan feuding had faded into a heroic history and Jacobitism might well have died a natural death had Westminster not fanned the dulling flames by passing Acts which were seen, not incorrectly, as Anti-Scottish. Across Scotland it appeared only servile agreement with Westminster would bring prosperity — anything else meant repression.

To both the disaffected and the genuine Jacobites it seemed natural to look to the previous dynasty as possible saviours. Even so, it is extremely possible there would have been no rising had the French, embroiled in yet another English — now British — war, not proposed an invasion of Britain with the objective of placing a Stuart upon the throne.

The idea flourished only briefly but when France changed her mind, Prince Charles Edward Stuart, son of The Old Pretender, James III, decided to force the issue by raising a rebellion which the French were bound to support. Aided by a handful of Franco-Irish privateers, the twenty two year old Charles left France to sail into Hebridean waters.

In late July of 1745, Charles anchored at the island of Eriskay and met with Alexander MacDonald of Boisdale who refused to participate in such a mad scheme, adding that MacDonald of Sleat and MacLeod of MacLeod shared his opinion of it. Ignoring the advice to return to France, Charles steered for the mainland and landed in the bay of Loch nan Uamh between Moidart and Arisaig on the 25th of July 1745.

The chiefs who came to see him were all Jacobites who had expected a few thousand French regulars to be there in support of the Prince. Lacking such solid aid they feared any Rising would fail but by persuasion and bribery Charles gradually brought them round to his ideas. On August 19th at Glenfinnan the flag of the Stuarts was again raised in Scotland.

Among the Highland Jacobites there were Clanranald, Cameron of Lochiel and MacDonald of Keppoch. Within a few days the news from Moidart had spread, other clans joined and the rashest adventure in Scotland's long martial history had begun in earnest.

JOHNNY COPE — If the Black Watch had not been transferred to King George's continental campaigns they might have been able to delay the advance of the Jacobites in 1745. Instead, Scotland was defended by Sir John Cope and three thousand regulars. Cope was neither a fool nor a coward and he marched to confront Charles first to Stirling then to Inverness hoping to muster the Whig clans along the way.

These tactics suited Prince Charles who avoided the General, captured Perth and then took Edinburgh. From Inverness Cope moved to Aberdeen then sailed south in a belated attempt to save the Capital. From Dunbar he harried his army along the golden shores of the Forth until, at Tranent, the redcoats contacted a picket of the Jacobites and Cope halted to choose his ground — at Prestonpans. He chose well, level killing ground fronted by a wide bog — there seemed no way the Highlanders could use their ferocious charge.

In the early afternoon of September 20th 1745 the Jacobite army arrived — two thousand untrained Highland militia, many of whom were grandsons of the victors of Killiecrankie — for the rest of that day the two armies surveyed one another. Cope had the advantage of position, artillery and cavalry. Charles appeared baffled, unsure of the correct tactics.

It was a local Jacobite named Anderson who came to the Prince's aid, guiding his army on a pre-dawn march through the bog to outflank the redcoats. Expecting some such move, Cope had lit watch fires and sent dragoons to guard his flanks. Shortly before the sun burned off the east coast haar, the dragoons made contact with the Highlanders and Cope wheeled his army to face the enemy.

The Highlanders came fast out of the dawn mist, fired their single volley and crashed into the redcoat lines. Catching the thrusting bayonets on their targes, they killed the bayoneter and continued slashing right and left with broadsword and dirk. Unable to fire and finding their bayonets ineffectual, demoralised further by the screaming slogans and ranting pipes, the redcoats broke, ran and were slaughtered. Cope, with Lord Loudon and Lord Hume, halted a troop of panicking dragoons but they refused to face the now rampant Highlanders and Cope was compelled to retreat.

While the Jacobites counted their booty and fifteen hundred prisoners, Cope was confessing his defeat to the garrison at Berwick where it was noted with some wit that he was the first General to bring the first news of his own defeat — such was the speed of his flight.

KING FAREWEEL — After Prestonpans Bonnie Prince Charlie controlled Scotland. Had he been satisfied then perhaps the strong anti-Union elements may have rallied to him and the Stuarts could have returned to reign in their ancient kingdom. Instead he followed the more ambitious course of tilting for the British throne and marched his Highland army deep into England.

Even though few English Jacobites joined him, Charles created panic among the courtiers of King George who were quickly recalling redcoat regiments from Flanders, when the Jacobites reached Derby there were three much larger Hanoverian armies closing in. The long retreat north began, punctuated by victories at Clifton and Falkirk, until eventually Charles led his gallant Highlanders onto Drumossie Muir on the 16th April 1746, to meet the massive army of the Duke of Cumberland, the son of King George.

The Battle of Culloden that followed should have been a one sided affair — only the courage of the clans kept the issue in doubt for a time. Outnumbered two to one, hammered by artillery and accurate volleys of musketry, those brave clans who reached the redcoat lines hacked their way through two battalions only to find others in support. The individual and collective heroism that had carried the Highlanders so far was now not nearly enough against the techniques of modem warfare — here at Culloden the Stuart dream died with many hundreds of its most loyal supporters.

In the bloody aftermath of the battle, Cumberland ordered the murder of the wounded and the ravaging of the glens in the most savage and brutal reprisals ever taken as he 'laid waste to the country of his enemy'. The rape, pillage and torture that methodically followed was not solely confined to those clans who supported the Stuarts, it was also applied to loyal subjects of King George as the army stamped its authority upon all Highland Scotland.

Having been led in disbelief from the bloody field, Prince Charles, with a price of £30,000 on his head (a price never collected despite the awful reprisals taking place in the country) had now begun his well chronicled escape and eventually sailed for France some months later.

He was to die in Italy in 1788 at the age of sixty eight years, an embittered and forgotten man whose rashness and vanity had cost Scotland dear. Yet when our national pride is stirred today, one cannot help imagining the clansmen and claymores of old defiantly marching again. In this enlightened age, it is with at least understanding, if not complete sympathy, that we may rightly say King fareweel, aye fareweel.