|

|

|

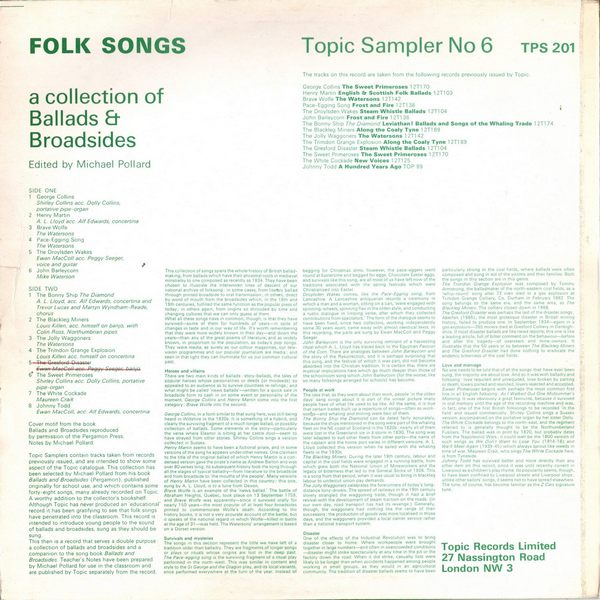

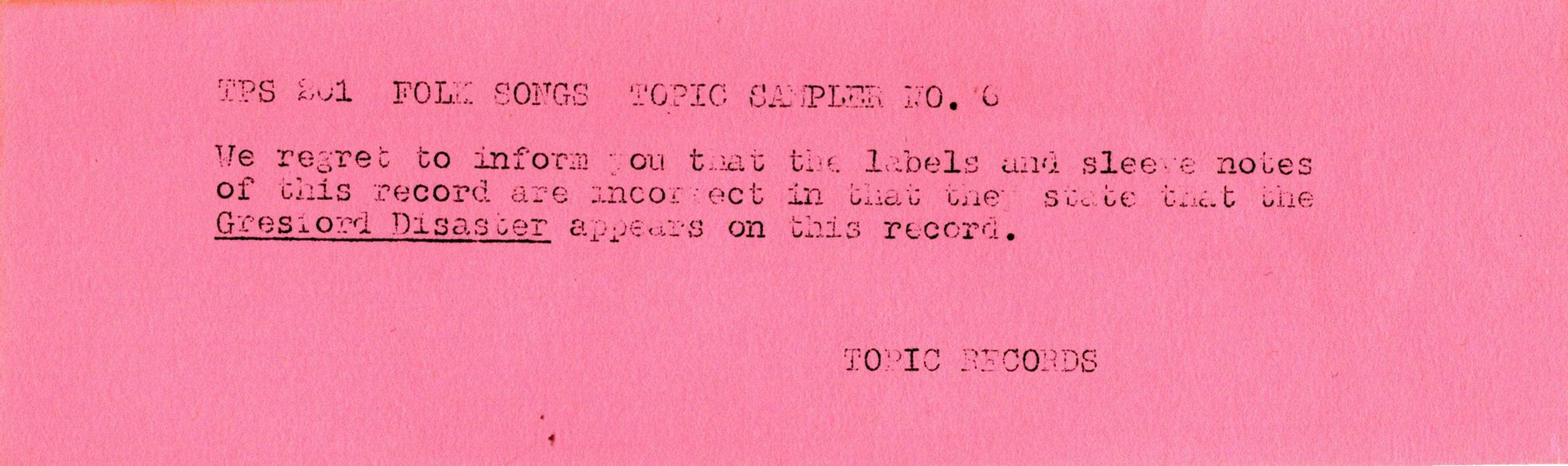

The above pink insert reads:

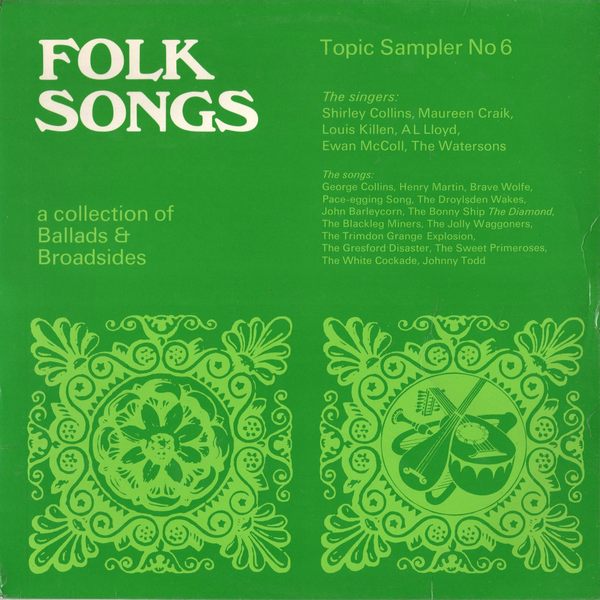

"TPS 201 FOLK SONGS TOPIC SAMPLER NO. 6

We regret to inform you that the labels and sleeve notes of this record are incorrect in that they state that the Gresford Disaster appears on this record.

TOPIC RECORDS"

Sleeve Notes

Topic Samplers contain tracks taken from records previously issued, and are intended to show some aspect of the Topic catalogue. This collection has been selected by Michael Pollard from his book Ballads and Broadsides (Pergamon), published originally for school use, and which contains some forty-eight songs, many already recorded on Topic. A worthy addition to the collector's bookshelf.

Although Topic has never produced an 'educational record it has been gratifying to see that folk songs have penetrated into the classroom. This record is intended to introduce young people to the sound of ballads and broadsides, sung as they should be sung.

This then is a record that serves a double purpose: a collection of ballads and broadsides and a companion to the song book Ballads and Broadsides. Teacher's Notes have been prepared by Michael Pollard for use in the classroom and are published by Topic separately from the record.

This collection of songs spans the whole history of British ballad-making, from ballads which have their ancestral roots in medieval minstrelsy to one composed as recently as 1934. They have been chosen to illustrate the interwoven lines of descent of our national archive of folksong: in some cases, from literary ballad through printed broadside to oral transmission; in others, direct by word of mouth from the broadsides which, in the 18th and 19th centuries, fulfilled the same function as the popular press of today; in others again, from origins so shrouded by time and changing cultures that we can only guess at them.

What all these songs have in common, though, is that they have survived — some of them for hundreds of years — in spite of changes in taste and in our way of life. It's worth remembering that they were more widely known in their day — and down the years — than any of the great poems of literature, and as widely known, in proportion to the population, as today's pop songs. They were media, as surely as our colour magazines, our television programmes and our popular journalism are media; and seen in that light they can illuminate for us our common cultural past.

Heroes and villains

There are two main kinds of ballads: story-ballads, the tales of popular heroes whose personalities or deeds (or misdeeds) so appealed to an audience as to survive countless re-tellings; and what might be called news ballads' — written for a quick sale in broadside form to cash in on some event or personality of the moment. George Collins and Henry Martin come into the first category; Brave Wolfe into the second.

George Collins, in a form similar to that sung here, was still being heard in Wiltshire in the 1920s. It is something of a hybrid, and clearly the surviving fragment of a much longer ballad, or possibly collection of ballads. Some elements in the story — particularly the verse where Eleanor is sitting at her castle door — seem to have strayed from other stories. Shirley Collins sings a version collected in Sussex.

Henry Martin seems to have been a fictional pirate, and in some versions of the song he appears under other names. One claimant to the title of the original ballad of which Henry Martin is a condensed version gave the pirate's name as Andrew Barton and was over 80 verses long. Its subsequent history took the song through all the stages of typical balladry — from literature to the broadside and from broadside to 'the mouths of the people'. Many versions of Henry Martin have been collected in this country; this one, sung by A. L. Lloyd, is to a tune from Devon.

Brave Wolfe is an example of the 'news ballad.' The battle of Abraham Heights. Quebec, took place on 13 September 1759. and Brave Wolfe was apparently — since it survived orally for i nearly 150 years — the most popular of at least four broadsides printed to commemorate Wolfe's death. According to the history books, it is not a very accurate account of the battle, but it speaks of the national regard in which Wolfe — killed in battle at the age of 31 — was held. The Watersons' arrangement is based on a Dorset version.

Survivals and mysteries

The songs in this section represent the little we have left of a tradition older than balladry. They are fragments of longer songs or plays or rituals whose origins are lost in the deep past. The Pace-egging song is the surviving fragment of a ritual play performed in the north-west. This was similar in content and style to the St George and the Dragon play, and its local variants, once performed everywhere at the turn of the year. Instead of begging for Christmas alms, however, the pace-eggers went round at Eastertime and begged for eggs. Chocolate Easter eggs, and survivals like this song, are all most of us have left now of the traditions associated with the spring festivals which were Christianised into Easter.

Droylsden Wakes comes, like the Pace-Egging song, from Lancashire. A Lancashire antiquarian records a ceremony in which a man and a woman, sitting on a cart, 'were engaged with spinning-wheels, spinning flax in the olden style, and conducting a rustic dialogue in limping verse, after which they collected contributions from spectators.' The form of the dialogue seems to have been fixed, since two collectors, working independently some 30 years apart, came away with almost identical texts. In this recording, the parts are sung by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger.

John Barleycorn is the only surviving remnant of a harvesting ritual which A. L. Lloyd has traced back to the Egyptian Passion of the Corn. There are analogies between John Barleycorn and the story of the Resurrection, and it is perhaps surprising that this song, and the festival of which it was part, did not become absorbed into the Christian tradition. It is certain that there are mystical implications here which go much deeper than those of the schoolroom song which John Barleycorn (for the worse, like so many folksongs arranged for schools) has become.

People at work

The idea that, as they went about their work, people 'in the olden days' sang songs about it is part of the unreal picture many people have of what life used to be like. All the same, it is true that certain trades built up a repertoire of songs — often as work-songs — and whaling and mining were two of them.

The Bonny Ship the Diamond can be dated fairly accurately, because the ships mentioned in the song were part of the whaling fleet on the NE coast of Scotland in the 1820s; nearly all of them were lost in the Greenland ice in a storm in 1 830. The song was later adapted to suit other fleets from other ports — the name of the captain and the home port varies in different versions. A. L. Lloyd collected this version when he sailed with the whaling fleets in the 1930s.

The Blackleg Miners. During the later 19th century, labour and capital in the coal fields were engaged in a running battle, from which grew both the National Union of Mineworkers and the legacy of bitterness that led to the General Strike of 1926. This is a song from that period, when it was usual to bring in blackleg labour to undercut union pay demands.

The Jolly Waggoners celebrates the forerunners of today's longdistance lorry-drivers. The spread of railways in the 1 9th century slowly strangled the waggoning trade, though it had a brief revival with the development of steam traction on the roads. (In our own day, road transport has had its revenge.) Generally, though, the waggoners had nothing like the range of their successors; the production of goods was more localised in those days, and the waggoners provided a local carrier service rather than a national transport system.

Disaster

One of the effects of the Industrial Revolution was to bring disaster closer to home. Where workpeople were brought together in large numbers — and often in overcrowded conditions — disaster might strike spectacularly at any time in the pit or the factory down the road. When it did strike, casualty lists were likely to be longer than when accidents happened among people working in small groups, as they would in an agricultural community. The tradition of disaster ballads seems to have been particularly strong in the coal fields, where ballads were often composed and sung in aid of the victims and their families. Both the songs in this section are in this genre.

The Trimdon Grange Explosion was composed by Tommy Armstrong, the balladmaker of the north-eastern coal fields, as a 'whip-round' song after 72 men died in a gas explosion at Trimdon Grange Colliery. Co. Durham in February 1882. The song belongs to the same era, and the same area, as The Blackleg Miners. The colliery closed down in 1 968.

The Gresford Disaster was perhaps the last of the disaster songs ; Aberfan (1966). the most grotesque disaster in British mining history, failed to produce one. In September 1934 — again in a gas explosion — 265 miners died at Gresford Colliery in Denbighshire. If most disaster ballads are like news reports, this one is like a leading article, full of bitter comment on the behaviour — before and after the tragedy — of overseers and mine-owners. It illustrates that the 50 years or so between The Blackleg Miners and The Gresford Disaster had done nothing to eradicate the endemic bitterness of the coal fields.

Love and marriage

No one needs to be told that of all the songs that have ever been sung, the majority are about love. And so it was with balladry and folksong: love requited and unrequited, love broken by parting or death, lovers parted and reunited, lovers rejected and accepted. Sweet Primeroses begins with perhaps the most common first line in all English folksong : As / Walked Out One Midsummer's Morning. It was obviously a great favourite, because it survived in oral memory until the age of the recording machine and was. in fact, one of the first British folksongs to be recorded 'in the field' and issued commercially. Shirley Collins sings a Sussex version, accompanied on the portative organ by her sister Dolly. The White Cockade belongs to the north-east, and the regiment referred to is generally thought to be the Northumberland Fusiliers. The ballad was in print by 1820, but probably dates from the Napoleonic Wars; it could well be the 1800 version of such songs as I've Don't Want to Lose You (1914-18) and We'll Meet Again (1939-45) which always sprout like weeds in time of war. Maureen Craik, who sings The White Cockade here, is from Tyneside.

Johnny Todd has survived better and more directly than any other item on this record, since it was until recently current in Liverpool as a children's play rhyme. Its popularity seems, though, to have been confined to Liverpool streets and Liverpool ships; unlike other sailors' songs, it seems not to have spread elsewhere. The tune, of course, has become familiar as the Z Cars signature tune.