Sleeve Notes

Dark Horse On The Wind

"This song is really the crystallization of my thoughts and feelings of Ireland: the anguish and the dread, the guilt and the cowardice of us all — not just the politicians or the bombers — the ambivalence of saying one thing, doing another; our continuing failure as humans in a situation where the mad dogs of all breeds shoot the people."

Smuggling The Tin

"This song tells the story of an expedition to smuggle tin across the border from Northern Ireland into what was then the Irish Free State, now the Irish Republic. In those days the word tinker meant a travelling tin smith and not a word of abuse. The tin used for soldering pots, cans, etc., was unobtainable in the southern part of the country, hence the smuggling. I learned this one from Francy Gavin, a merry little rogue who drowned his sorrows in a sea of porter."

The Blue Tar Road

"The plastic age, which having destroyed the traditional trade of the travellers, forced them to move into urban areas in large numbers, and what had hitherto been a side line, begging, became literally a life line. The government white paper of 1963 states some 80% of the travellers have no other means of life. The same government jail them for begging — some justice. The song describes some incidents, when travellers were being pushed from pillar to post by the corporation and even some mortgage-minded vigilante type citizens. Rory Cowen, the one lone voice to cry halt to the corporation, and Joe Donohoe, leading the travellers' Labre Park first official chalet-type camp site, was the end result. Lansdown Valley is off the Naas Road. Cherry Orchard is in Upper Ballyfermot where I live. The blue tar road is the asphalt road a shimmer under a blue sky."

The Town Of Castle d'Oliver

"This song is one of the many which I had literally followed for years before I finally caught up with the corpse. First heard it about '58, and learned two verses off the man who sang it. I don't think he had any more of it, but he would not, or could not, sing the rest. About '60/'61 I heard a woman sing an additional verse. A blank space till about '64 when to my joy, I heard a traveller singing it at Puck Fair. I asked him to sing it again, and bingo, we had her snared."

James Connolly

"My own favourite song of Ireland's greatest socialist revolutionary. The song is a fairly recent one, but anonymous as far as I know. The first person I heard singing it was Johnny Flood, a friend of mine and a fine singer. I sometimes tack on an extra verse when I sing it, but here I sing it as I heard it originally — well, more or less."

My Love Is A Well

"Written about 1959, for my first wife whom I haven't buried yet: the difficulty is she's not dead. There's not much I can say about this one, as it should explain itself. Compare it with the other love song, 'Via Extasia', and remember there is a seventeen year interval between them."

SIDE TWO:

Via Extasia

"A song of love on many different levels, physical and metaphysical. If you listen with your heart, let it flow round, over and through you — you will get the idea — through love, union with the absolute, in other words, Nirvana."

The Well Below The Valley

"I learned this song from the singing of Mary Duke, a big large-boned woman with high cheek bones and up-tilted eyes, which made her look more gipsy than any of the travelling people, who are not gipsies, but displaced Irish people. Its archaic quality struck me like a blow. Supposed to be a fragmentary version of 'Jesus and the woman at the well'."

Wild Croppy Tailor

"This song, English in origin, is a little different to some versions I have heard. It seems much more common in Northern Ireland than in the South. I learned it in the early sixties from a neighbour, Mrs. Carmel Callas, who learned in in turn from her father."

Barbary Allen

"Lazy days and Summer breezes, lying in a ditch hoping the catting bird would keep singing, and the brace hen would not entangle herself in her harness. Dickie Masterson, bird catcher and trapper — "singing birds, of course; if they didn't sing they wasn't birds." Dickie, five foot six, bushy eyebrows, once white walrus moustache stained a Woodbine ivory under a nose that was a living monument to himself; his Summer/Winter gear of hobnailed boots and long woollen army coat, singing to pass the time in his public-house tenor voice, everything from Martha to Barbary Allen. I being descended from a long line of birdcatchers, horse copers and chancers, I wasn't long in snaring Barbary Allen for myself — I've loved her ever since."

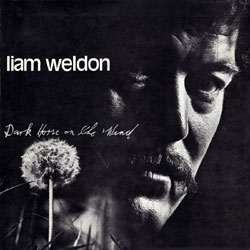

Jinny Joe

"Dublin children call the seed parachute of the dandelion a jinny joe. My eldest son, Brendan, who is sixteen now, was at the time about four or five, and I was walking in the park with him one day. He was hopping along as kids do, he bent down, plucked a dandelion seed head, and blew the seed into the wind. As I idly watched the drifting down, it suddenly struck me that I had cast him into the world just as he had cast the jinny joe, and with as much control over his destiny as he had over the seed. I made this song to alleviate my sorrow."

Liam Weldon (15th October 1933 - 28th November 1995)

Liam Weldon was born in the Coombe Hospital on the 15th of October, 1933 — "of a long line of Liberties heads." He claims his people have been in Dublin since the 12th century, and they've had a cottage in Hanbury Lane for 200 years.

His father bred and raced greyhounds, played general factotum for a bookie. After a good meeting at Harold's Cross, the father and his cronies used take a cab (never a taxi, that was infra dig) into town for a spree, dropping young Liam off near home with money for the mother and several half-crowns for himself.

Behind the Hanbury Lane cottages there was a big yard, with sheds for pigs, goats and ice-cream vendors. Granny was the matriarch. Her husband was batman to Holy Father Willie Doyle in the '14 war, with a medal to prove it ("for ducking at the right time", said the tongues of mischief). Back home he drank deep, but his wife ran the fruit-veg-and-fish boutique. She went to Seven Mass in Meath Street every morning, did all her own baking, her hands never idle save when under her apron — and not even then: the boy soon twigged their movements: she was saying her beads …

There was no music in the family but Liam got it from the travellers his granny let stay in the yard — two families with their wagons. At nine years of age he'd be feeding his father's greyhounds and hearing the old travelling women singing, he'd stop to listen, getting the ripple up and down his spine, and the old women would notice him listening and say: "Aren't you the quare little sham? You're not always throwing cans at the nanny-goats." Sham means man in travelling-talk, or gammon as it's called — Liam learnt to speak it from the kids in the yard. And he knew, no need to "learn" it, that those kids, his coevals, and those old singing women, were as human as anyone else — in Foxrock or Thomas Street. Years later he wrote a song stemming from that: The Blue Tar Road. Many people born "more privileged" (which in a context like this may in fact mean less so) could learn from this great magnanimous song of human brotherhood.

His mother's father was a bird-catcher, a lark man. He used to go out to Greenhills where the larks were then prevalent. As the city crept out, he had to go further afield — to Brittas, then Walkinstown. But always he kept to the south side, no question of that north lark. The nets for larks were big, two men to handle them.

Dicky Masterson, a crony of his bird-catching granda, took him out with brace-hens calling birds (or decoys) for linnet and goldfinch. They could catch up to 30 birds at a time in spring-nets.

Once admiring buntings Liam said: "Aren't they lovely birds, Dicky?" Dicky replied: "Sure them is not birds, sure they can't sing." Bird meant song-bird, only. And birds never whistled, they sang. You were hopped on if you said "whistled."

He started mending guitars and making mandolins. He'd already made a Bodhrán or two for himself but now he began to make them for sale. That was in the Sixties, they fetched from £7 to £18.

Round '68 he became a fitter's mate, installing boilers, grills, and giant cookers in hotels. This took him all over the country, which fitted in very well with his appetite for songs. First thing in every new town was finding the music — filling in the missing verses of old songs he already had most of, acquiring new songs, listening to the pipers and fiddlers.

About that time a lad called Patsy Brennan, who was "into Dylan" and played steel guitar, asked Liam to join him, with Johnny Flood on Spanish guitar. The sessions were in the Central Bar in Aungier Street, and that's how the Pavees started — but in the long run Liam prefers to sing solo, unaccompanied. This puts him firmly in a tradition even stronger in Connacht than in Dublin.

The first man to put Weldon on television was Tony MacMahon, but he was far more benefit to him than just that. He gave him a regular spot but he also pointed out how Liam could slur — the worst thing a singer can do. This made Liam realise more fully than before that singers sing not just for themselves but for others to hear. (Think of all the lovely voices whose possessors have never realised that, their God-given voices wasted, pointless). Tony taped Liam and played it back to him to show him. That's what's called constructive criticism and Liam regards it as a turning point. TV and radio in general were good for his discipline and self-criticism, stopped him running on too long, made him prune.

In 1966 he was painting steel girders and when the powers-that-be started celebrating the Rising he began to feel pretty bitter. Cherish the children mar dhea: he thought of the men of '16, whirling like tops or deverishes in their graves and half the country still in the hands of grabbers, native or foreign. So to counter the lip-service a bit, he made up the song, "Dark Horse on the Wind". It's against false glory, against hyprocrisy, and it has more hope in its disillusionment (because more truth) than all the sham celebrations. The way those two great mythologies, Greek and Irish, come together at the end of it, is natural and easy and fitting; I'll wager a harp to a halo both Connolly and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington would have relished it:

In grief and hate our motherland her

dragons' teeth has sown.

Now the warriors spring from the

earth to maim and kill their own.

Rise Rise Rise! Dark horse on the

wind —

For the one-eyed Balor still reigns king

In our nation of the blind.

Liam Weldon finds the tops of buses good for making up songs. With any luck you're alone there or nearly alone, with no distractions, and there's movement all the time and what is life but movement — and what are songs but moving sound?

Apart from what he learnt from the travelling people, the boy was taken by the slow airs he heard on the pipes or on old rickety melodeons. And after his folk moved to Aungier Street, where they'd no wireless, he'd walk to his granny's in Hanbury Lane every Sunday morning to listen, on her old battery-radio, to Seamus Ennis's now legendary programme, "As I Roved Out". He learnt a lot from that — tho' he still has no time for what he calls "the academic English mangel-wurzel merchants."

One day he stood long in the street listening to a singer, gave him what a little boy could — "not charity but paying him for giving me something." On his way to the Adelaide, another time, as a ten-year-old out-patient, he heard a man singing "The Miller's Daughter". He knew the first two verses himself and sang them: the man said: "Me brave man, you'll make a fair little ballad-singer yourself." Liam Og bought a ballad-sheet from him, for an English threepenny-bit (which left him sixpence for sweets). He bowled onwards to the children's party at the hospital, where he sang his now complete version of "The Miller's Daughter" and won a prize for it: "Tom Brown's Schooldays". He lapped it up — like other books, especially natural history (Kevin Street Library was a boon) — but he couldn't see why the people in it were so scared of hard liquor: round Hanbury Lane people downed it all the time, given half a chance, and never seemed worried …

When his father died at 37, of pneumonia and asthma, leaving his mother with 7 kids and a non-contributory widow's pension, scrubbing stairs for dear life, 14-year-old Liam needless to say left school. He was a messenger boy till 16. Then he sent shekels back from England for several years. At 22 he came back, with a fiver and no prospects, to marry a girl from Blackpitts called Nellie. The wedding took place in Ballyfermot, Nellie's brother was a baker so the wedding cake was no bother. The ten bob Liam slipped to the priest was tattered, much to the priest's dismay — but life since then has been "one tattered ten bob after another …

They lived in Chambers Street for two years, then moved to Ballyfermot. After five months of marriage Liam got a job in a woollen mill in Walkinstown. He stuck it for 8 years — dust, fluff, lint, lousy conditions and a barely living wage — and at least it squeezed out of him the first song he made up for himself. "My Love is a Well" was made up thinking of Nellie, as he handled the loose, damp sheep's wool into huge hoppers, made in Huddersfield early on in the first glorious dawn of the Industrial Revolution but still going strong (or decrepit) in Walkinstown, not far from birdsong.

When the woollen mill folded he got £150 redundancy, after that the family helped out a bit. Things were rough. Somebody who'd heard him singing offered him a spot, so he didn't refuse. Between singing and "the labour", two years. Then I agree with him about the top decks of buses, the world always looks new from there and what are songs but hope? But that's not enough either. There are songs to which hope is irrelevant, even inadequate — "Via Extasia" is one. Of all the songs on this record it's the one that takes (for me) most listening. Love can go beyond hope.

Yet there's always hope in anyone singing as well as this man sings on this record, singing words as true and as deeply felt as these, in this voice both lonely and full of power. This is Dublin singing and Irish singing, as Dublin as the Easter Rising, as Irish as the Love Songs of Connacht or Flanders fields or the Limerick Soviet that got clobbered.

In tempo, in depth of feeling and understanding, in atmosphere, Liam Weldon is the only Irishman singing in English who reminds me, often and inescapably, of the Gaelic Sean-nós; yet with no superficial imitation. It's a matter of kindred spirit. The same tenderness is there (most of all in the unforgettably poignant "Jinny Joe") and the same tragic power that goes far beyond protest without ever reneging on it.

It's no accident Liam first learnt his singing from the travellers, whom he calls (in his note about "Smuggling the Tin") "displaced Irish people." As long as Dublin can still breed a singer like this, the Irish are not utterly displaced, and Ireland's soul is still her own.

Pearse Hutchinson.

In The Singing of a Song

My pulse runs in a scarlet flood,

my thoughts swim in a heady wine

deep and dark.

My words fall,

syllabic leaves

on the breath of an Autumnal wind.

I blow.

Blow wind and words

my life to tell,

telling my life,

telling my life to all,

my life to all,

in a song.

Screaming my life

in a song,

screaming my very existence.

I once was here …

in the singing of a song.

© Antaine Ó Faracháin,

2 Feabhra 1999.

Words, music, the person, life played out for a few moments, shared distilled wisdom, personal insight, things that can't be said in any other way, layers of meanings, surges of emotions, laughs, tears, screams, company … an affirmation that I am alive, and that I know I am. I am eternally alive in the words that pass from my lips to others and in the words that have come forth from others to me, and all those who have amassed this wisdom are alive within me, echoing their wisdom within. All those poets sing me as a song and the song asserts my life. The song sings me as I sing it.

Liam Weldon was a man who thought about life, who had a respect for life and for nature and for people. There was an honesty about the way he saw things. His sense of fun and his sense of humour he often shared, setting the company laughing with his sharp one-liner wit. He was also a man who had a sense of poetry and who earned the respect of poets. Although Liam has passed away he is one of those who echo within me, his words, his thoughts, his emotions. He sings with me and he sings within me. He is in my company. He is in all our company, alive in the songs he has left us, in their petals and in their thorns …

"And were you then the last wild leaf, on the Autumn bough,

I the wind, a wanton thief, to blow as I blow now,

And when you'd fall, as fall you must, I to be the waiting dust,

Beyond sorrow, pain or lust,

And to live forever, truly one … " (Liam Weldon)

"Sin a bhfuii … "

Antaine Ó Faracháin,

2 Feabhra 1999.