|

|

Sleeve Notes

The land itself is a song. In the late spring, when the soft morning rain falls and the afternoon sun warms to the season, Ireland is a song of color. Its fields are dipped in several shades of green, a patch-work of stark emerald and delicate lime, sun bleached meadows wear pale golden faces. Whine bushes grow in wild patches along the tops of dirt brown ditches and blossom finally in a sunburst of summer yellow. Below them, thin-stemmed legions of white daisies skirt the roadside and bend with the wind that moves through the country. On flat stretches of coal black boglands, the heather grows in coarse purple-blue bunches around bottomless big lakes. And all along the sea beaten Western coast, the clouds come in low and fast off the North Atlantic, eclipsing mountain peaks and making one think of film director John Huston's remark that "the greatest drama in the world is in the Irish sky".

Travel across the face of this land that is a song and it is easy to understand why the language and music flow so naturally out of its people. For if the Irish are poor by our economic measurements, they are far richer in other areas that should matter far more. Their wealth lies in the pace of life, in their spirit and in the special gift that is their music. There are examples of that wealth everywhere. For instance, in Drumkeeran, a one-street town in the poorest part of rural Ireland, there is a farmer named Pat Phildy McGowan who is a concert all by himself. He has never taken a music lesson and yet he can pick up a tin whistle, or an accordian, or a fiddle or a flute, or a harmonica or even a set of spoons and play away on them through the night until the morning sun signals him to stop. He plays hundreds of traditional jigs and reels with marvelous titles like "The Pig's Lament Over The Empty Tub" and he sings songs whose lyrics take you through happy wars and tragic love affairs, to wakes with whiskey, town fairs, brothels, chapels and out to ships at sea.

But not all the Pat Phildy McGowans were able to stay in a land that could not support them. And so they left it in waves, fleeing westward like the legendary wild geese to discover America's far away dream or moving across the Irish Sea in boats to make their money in bleak, industrial English towns. Wherever they settled they brought with them the wealth of their music.

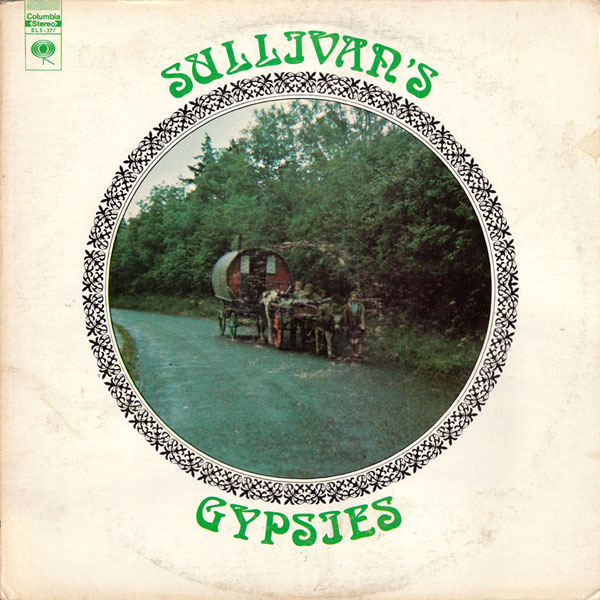

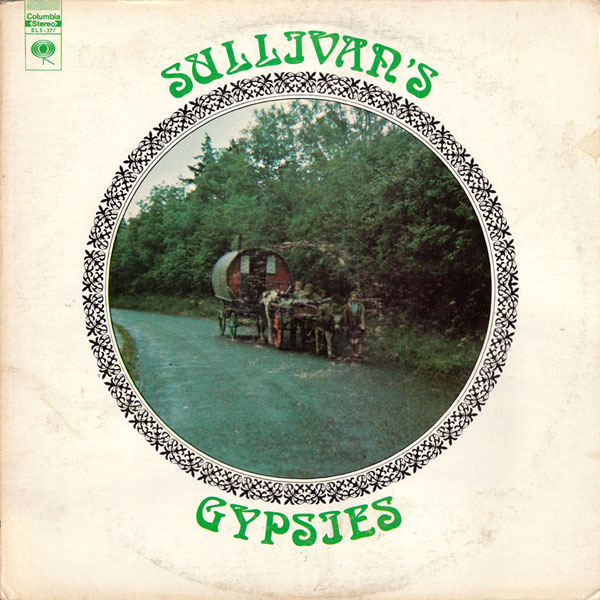

A few years ago, five young Irishmen followed the similar pattern. One of them came out of a village in Tipperary, another from the town of Omagh in troubled Northern Ireland and three others from the streets of mother Dublin. Like the wild geese their route was westward. Somehow they all ended up in Toronto and somehow music brought them all together there. They called themselves Sullivan's Gypsies and went out together across Canada raising songs and raising hell. My baptism with them came on what I had expected would be a dull Monday night of conservative drinking in a bar New York's Greenwich Village, a drinking house frequented by occasional and full time writers, artists, singers, seamen off-duty barmen, political journeymen, various Irishmen who all claim they were with James Connolly in the Dublin GPO during the '16 Rising and one Communist brewery worker. At about 10 o'clock, strange things began to happen. Tom Clancy of the folksinging Clancy Brothers arrive in off the street to announce the arrival of a new heiress.

" The wife's given birth," Tom shouted to the bar. A lovely young girl. I took one look at the baby and said we're naming it Blawneen, Little flower. We'll have a drink on the strength of that."

Great cheers greeted that suggestion. Guiness flowed. Shot glasses went damp with Jameson Irish whiskey. A crowd swelled around Clancy, handshaking and back-slapping at him while outside a full moon shone down on the city like some round yellow omen of what was to come. An hour passed. The door swung open then in off the street tumbled Seán McCarthy, an Irish folk poet, singer, song writer, author and story-teller who spends his time wandering around the western world asking people to come on back to old Lixnaw in County Kerry to have an old drink with him. In behind McCarthy tramped Sullivan's Gypsies, all of them big enough men with generous portions of hair on their faces and heads. McCarthy introduced them all around.

There was the leader of the group, Don Sullivan, a monster sized man whose face is a fleshy fortress camouflaged with a curly bush of black hair. And there was Dennis Ryan, the tall gentle Tipperary man who wears the expression of an altar boy who has forgotten his prayers. And then there were the three men from mother Dublin, all of them bearing names that seem to have music in them, all of them equipped with sharp Dublin street accents that attack the ear drums of the listener.

There was Fergus O'Byrne, standing there and peering out from behind his John Lennon Lyndon Johnson granny glasses, his s head of hair falling onto his shoulders like living room drapes. And beside him was Gary Cavanaugh, the wearer of a strawberry red head which puts a top on a face whose expression is capable of going from the look of virgin innocence to bedroom roguery in one easy transformation. And holding up the rear was Dermott O'Reilly, a fellow whose smile is unrehearsed and whose reputation on the guitar had preceded him to New York.

With introductions in order, someone in the crowd mentioned the word 'singsong'. With that, there was a huge flush of people into the bar's backroom. The five Gypsies began to unpack their musical tools — two guitars, a banjo, tin whistle, mandolin and fiddle. Meanwhile, McCarthy was trying to order another drink. He summoned a tall, thin black waitress. "Ara, how are you gettin' on, love?" he greeted her. She strained at his Kerry accent. "Now love, all these lads have a diabolical thirst so bring us an old drink. Four or five big bottles of champers all around. and, Jasus, make sure it's icy, love." The waitress looked at McCarthy like he was some kind of alien. Which he was. "What's champers?", she asked in a tone that mode boredom sound interesting. McCarthy tried again: "Ah sure, the bubbly, love, the old bubbly. What in the name of the sufferin' Jasus do you call it in this diabolical country? Ah, the French stuff, love, the champagne. That's it, champagne. Go on off now before we dry up with the thirst." Soon the champagne flowed. And then the music. The sound came up out of those musical tools the Gypsies held and filled the back room and carried out along the bar. The sing-song was on.

There were five voices raised in song now, moving through a great piece of work called "The Rising of The Moon", a song about men rising in revolution, a song which has poetry for lyrics.

When they finished it, Fergus O'Byrne lifted his banjo, and lifted his voice in "Paddy On The Railway", a song which seems to suspend itself in the chorus. The quiet man, Dennis Ryan shifted into position next, setting down his fiddle on the table and tucking his tin whistle into his back pocket. His two hands caught a hold of the open edges of his tweed vest, giving him the studied look of a railroad conductor between ticket collections. There was no sound in the room as he began to sing "The West' s Awake", a lovely song which tells how West Ireland came out of its "slumber deep" to awaken and learn liberty. I have heard this song sung by countless people on countless occasions for countless reasons but I have never heard anyone sing it quite like Dennis Ryan. His indeed the definitive version.

As the night wore on into the early morning, songs kept on being sung and the tall, thin black waitress kept on bringing the champers, Guiness and Jameson, which was the fuel that fed the voices and kept the musical machine well oiled. Since that mad evening, I have spent many a night in pubs and folksinging houses in the U.S., Canada and Ireland listening to Sullivan's Gypsies fill them with the music that is Ireland's wealth.

Part of that wealth is on this album; the voices of five men singing with gusto and rough charm the songs of the country that produced them. it is the singsong all over again. Sit down, loosen your tie, put a bottle of champers on ice and sing along.

I think you'll be glad you stopped by.

Jack Deacy

(Jack Deacy is a 26-year-old columnist for the New York Daily News. His Column, which appears three times a week, touches on politics, entertainment, drinking, gambling etc.)