|

|

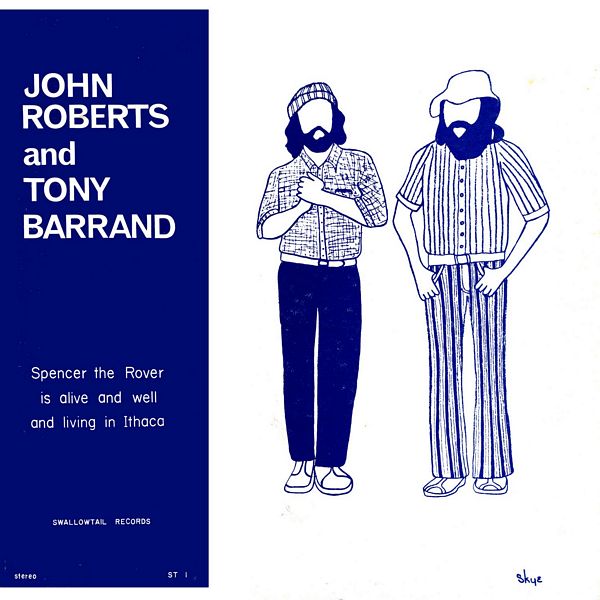

Sleeve Notes

English Traditional Ballads and Songs (mostly)

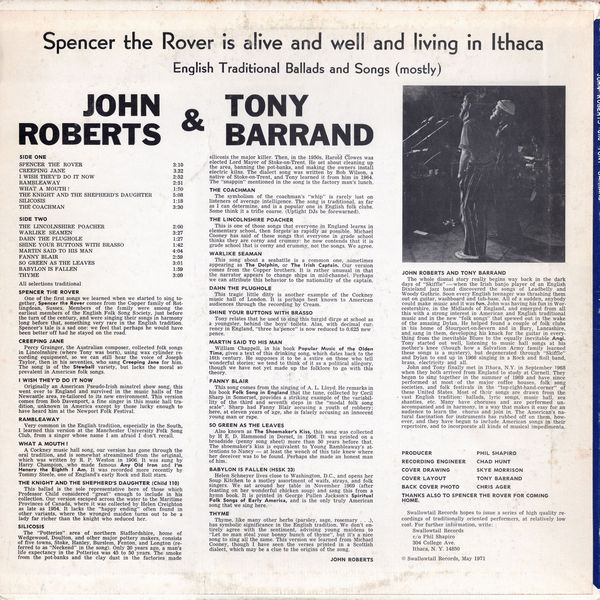

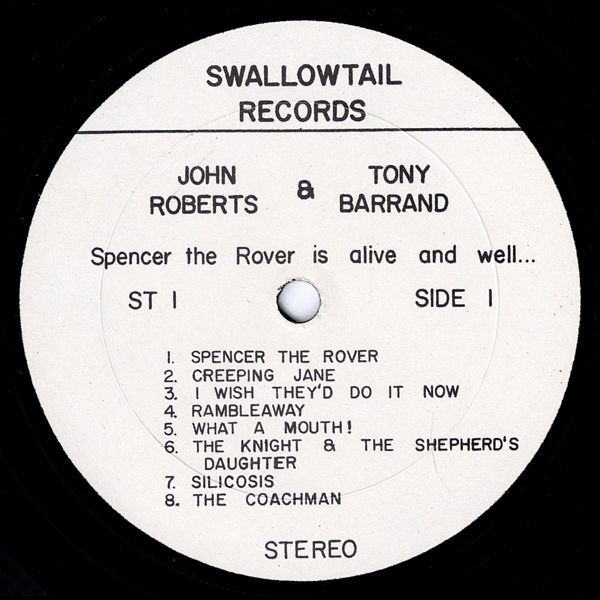

Spencer The Rover — One of the first songs we learned when we started to sing together, Spencer the Rover comes from the Copper family of Rottingdean, Sussex. Members of the family were among the earliest members of the English Folk Song Society, just before the turn of the century, and were singing their songs in harmony long before that, something very rare in the English tradition. Spencer's tale is a sad one: we feel that perhaps he would have been better off had he stayed on the road.

Creeping Jane — Percy Grainger, the Australian composer, collected folk songs in Lincolnshire (where Tony was born), using wax cylinder recording equipment, so we can still hear the voice of Joseph Taylor, then in his seventies, who sang Creeping Jane for him. The song is of the Stewball variety, but lacks the moral so prevalent in American folk songs.

I Wish They'd Do It Now — Originally an American Pseudo-Irish minstrel show song, this went over to England and survived in the music halls of the Newcastle area, re-tailored to its new environment. This version comes from Bob Davenport, a fine singer in this music hall tradition, unknown in America except by those lucky enough to have heard him at the Newport Folk Festival.

Rambleaway — Very common in the English tradition, especially in the South, I learned this version at the Manchester University Folk Song Club, from a singer whose name I am afraid I don't recall.

What A Mouth! — A Cockney music hall song, our version has gone through the oral tradition, and is somewhat streamlined from the original, which was written by R. P. Weston in 1906. It was sung by Harry Champion, who made famous Any Old Iron and I'm Henery the Eighth I Am. It was recorded more recently by Tommy Steele, one of England's early Rock and Roll stars.

The Knight And The Shepherd's Daughter (Child 110) — This ballad is the sole representative here of those which Professor Child considered "great" enough to include in his collection. Our version escaped across the water to the Maritime Provinces of Canada, where it was collected by Helen Creighton as late as 1954. It lacks the "happy ending" often found in other variants, where the wronged maiden turns out to be a lady far richer than the knight who seduced her.

Silicosis — The "Potteries" area of northern Staffordshire, home of Wedgewood, Doulton, and other major pottery makers, consists of five towns, Stoke, Hanley, Burslem, Fenton, and Longton (referred to as "Neckend" in the song). Only 20 years ago, a man's life expectancy in the Potteries was 45 to 50 years. The smoke from the pot-banks and the clay dust in the factories made silicosis the major killer. Then, in the 1950s, Harold Clowes was elected Lord Mayor of Stoke-on-Trent. He set about cleaning up the area, banning the pot-banks, and making the owners install electric kilns. The dialect song was written by Bob Wilson, a native of Stoke-on-Trent, and Tony learned it from him in 1964. The "snappin" mentioned in the song is the factory man's lunch.

The Coachman — The symbolism of the coachman's "whip" is rarely lost on listeners of average intelligence. The song is traditional, as far as I can determine, and is a popular one in English folk clubs. Some think it a trifle coarse. (Uptight DJs be forewarned).

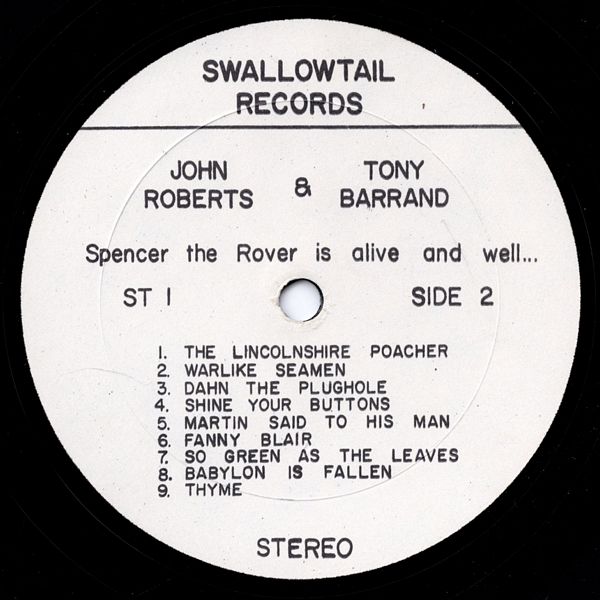

The Lincolnshire Poacher — This is one of those songs that everyone in England learns in elementary school, then forgets as rapidly as possible. Michael Cooney has said of these songs that everyone in grade school thinks they are corny and crummy: he now contends that it is grade school that is corny and crummy, not the songs. We agree.

Warlike Seaman — This song about a seabattle is a common one, sometimes appearing as The Dolphin, or The Irish Captain. Our version comes from the Copper brothers. It is rather unusual in that the narrator appears to change ships in mid-channel. Perhaps we can attribute this behavior to the nationality of the captain.

Dahn The Plughole — This tragic little ditty is another example of the Cockney music hall of London. It is perhaps best known to American audiences through the recording by Cream.

Shine Your Buttons with Brasso — Tony relates that he used to sing this turgid dirge at school as a youngster, behind the boys' toilets. Alas, with decimal currency in England, "three ha'pence" is now reduced to 0.625 new pence.

Martin Said to His Man — William Chappell, in his book Popular Music of the Olden Time, gives a text of this drinking song, which dates back to the 16th century. He supposes it to be a satire on those who tell wonderful stories; we tend to think of it as a political allegory, though we have not yet made up the folklore to go with this theory.

Fanny Blair — This song comes from the singing of A. L. Lloyd. He remarks in his book Folk Song in England that the tune, collected by Cecil Sharp in Somerset, provides a striking example of the variabillity of the third and seventh steps in the "modal folk song scale". Sharp had Fanny Blair accusing a youth of robbery; here, at eleven years of age, she is falsely accusing an innocent young man or rape.

So Green as The Leaves — Also known as The Shoemaker's Kiss, this song was collected by H E. D. Hammond in Dorset, in 1906. It was printed on a broadside (penny song sheet) more than 50 years before that. The shoemaker's kiss is equivalent to Young Rambleaway's attentions to Nancy — at least the wench of this tale knew where her deceiver was to be found. Perhaps she made an honest man of him.

Babylon Is Fallen (HSSK 23) — Helen Schneyer lives close to Washington, D.C., and opens her Soup Kitchen to a motley assortment of waifs, strays, and folk singers. We sat around her table in November 1969 (after feasting on her wonderful chicken soup) and sang this from a hymn book. It is printed in George Pullen Jackson's Spiritual Folk Songs of Early America, and is the only truly American song that we sing here.

Thyme — Thyme, like many other herbs (parsley, sage, rosemary . . .), has symbolic significance in the English tradition. We don't entirely agree with the sentiment, advising young maidens to "Let no man steal your bonny bunch of thyme", but it's a nice song to sing all the same. This version we learned from Michael Cooney, though I have seen the verses printed in a Scottish dialect, which may be a clue to the origins of the song.

John Roberts

John Roberts & Tony Barrand

The whole dismal story really begins way back in the dark days of "Skiffle" — when the Irish banjo player of an English Dixieland jazz band discovered the songs of Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie. Soon every English teenager was thrashing them out on guitar, washboard and tub-base. All of a sudden, anybody could make music and it was fun. John was having his fun in Worcestershire, in the Midlands of England, and emerged from all this with a strong interest in American and English traditional music and in the new "folk songs" that spewed out in the wake of the amazing Dylan. He helped found a couple of folk clubs in his home of Stourport-on-Severn and in Bury, Lancashire, and sang in them, developing his knack for the guitar in everything from the inevitable Blues to the equally inevitable Angi. Tony started out well, listening to music hall songs at his mother's knee (though how a Salvation Army family learned these songs is a mystery), but degenerated through "Skiffle" and Dylan to end up in 1966 singing in a Rock and Roll band, brass, electricity and all.

John and Tony finally met in Ithaca, N.Y. in September 1968 when they both arrived from England to study at Cornell. They began to sing together in the summer of 1969 and have since performed at most of the major coffee houses, folk song societies, and folk festivals in the "top-right-hand-corner" of these United States. Most of their songs are drawn from the vast English tradition: ballads, lyric songs, music hall, sea shanties, etc. Many have choruses and are performed unaccompanied and in harmony, in a way that makes it easy for an audience to learn the chorus and join in. The American's natural fascination for instruments has rubbed off on them, however, and they have begun to include American songs in their repertoire, and to incorporate all kinds of musical impedimenta.