|

|

Sleeve Notes

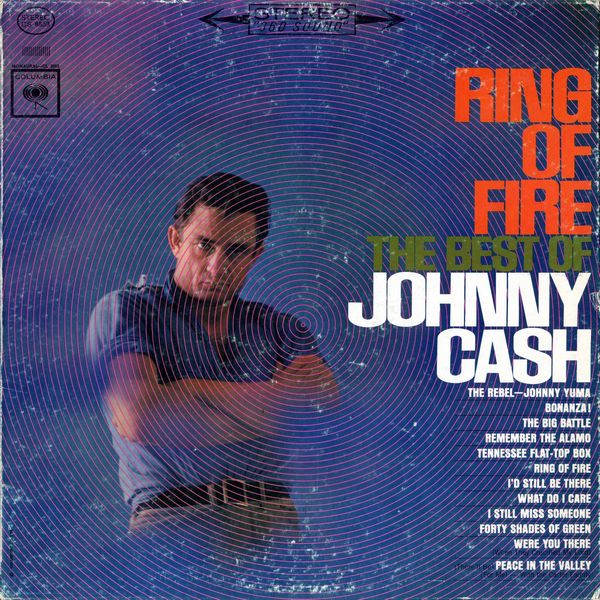

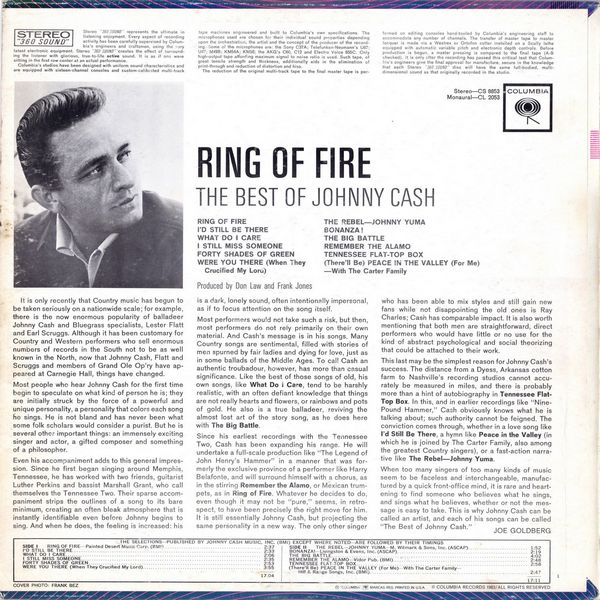

It is only recently that Country music has begun to be taken seriously on a nationwide scale; for example, there is the now enormous popularity of balladeer Johnny Cash and Bluegrass specialists, Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs. Although it has been customary for Country and Western performers who sell enormous numbers of records in the South not to be as well known in the North, now that Johnny Cash, Flatt and Scruggs and members of Grand Ole Op'ry have appeared at Carnegie Hall, things have changed.

Most people who hear Johnny Cash for the first time begin to speculate on what kind of person he is; they are initially struck by the force of a powerful and unique personality, a personality that colors each song he sings. He is not bland and has never been what some folk scholars would consider a purist. But he is several other important things: an immensely exciting singer and actor, a gifted composer and something of a philosopher.

Even his accompaniment adds to this general impression. Since he first began singing around Memphis, Tennessee, he has worked with two friends, guitarist Luther Perkins and bassist Marshall Grant, who call themselves the Tennessee Two. Their sparse accompaniment strips the outlines of a song to its bare minimum, creating an often bleak atmosphere that is instantly identifiable even before Johnny begins to sing. And when he does, the feeling is increased: his is a dark, lonely sound, often intentionally impersonal, as if to focus attention on the song itself.

Most performers would not take such a risk, but then, most performers do not rely primarily on their own material. And Cash's message is in his songs. Many Country songs are sentimental, filled with stories of men spurned by fair ladies and dying for love, just as in some ballads of the Middle Ages. To call Cash an authentic troubadour, however, has more than casual significance. Like the best of those songs of old, his own songs, like What Do I Care, tend to be harshly realistic, with an often defiant knowledge that things are not really hearts and flowers, or rainbows and pots of gold. He also is a true balladeer, reviving the almost lost art of the story song, as he does here with The Big Battle.

Since his earliest recordings with the Tennessee Two, Cash has been expanding his range. He will undertake a full-scale production like "The Legend of John Henry's Hammer" in a manner that was formerly the exclusive province of a performer like Harry Belafonte, and will surround himself with a chorus, as in the stirring Remember the Alamo, or Mexican trumpets, as in Ring of Fire. Whatever he decides to do, even though it may not be "pure," seems, in retrospect, to have been precisely the right move for him. It is still essentially Johnny Cash, but projecting the same personality in a new way. The only other singer who has been able to mix styles and still gain new fans while not disappointing the old ones is Ray Charles; Cash has comparable impact. It is also worth mentioning that both men are straightforward, direct performers who would have little or no use for the kind of abstract psychological and social theorizing that could be attached to their work.

This last may be the simplest reason for Johnny Cash's success. The distance from a Dyess, Arkansas cotton farm to Nashville's recording studios cannot accurately be measured in miles, and there is probably more than a hint of autobiography in Tennessee Flat-Top Box. In this, and in earlier recordings like "Nine-Pound Hammer," Cash obviously knows what he is talking about; such authority cannot be feigned. The conviction comes through, whether in a love song like I'd Still Be There, a hymn like Peace in the Valley (in which he is joined by The Carter Family, also among the greatest Country singers), or a fast-action narrative like The Rebel — Johnny Yuma.

When too many singers of too many kinds of music seem to be faceless and interchangeable, manufactured by a quick front-office mind, it is rare and heartening to find someone who believes what he sings, and sings what he believes, whether or not the message is easy to take. This is why Johnny Cash can be called an artist, and each of his songs can be called "The Best of Johnny Cash."

Joe Goldberg