|

|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

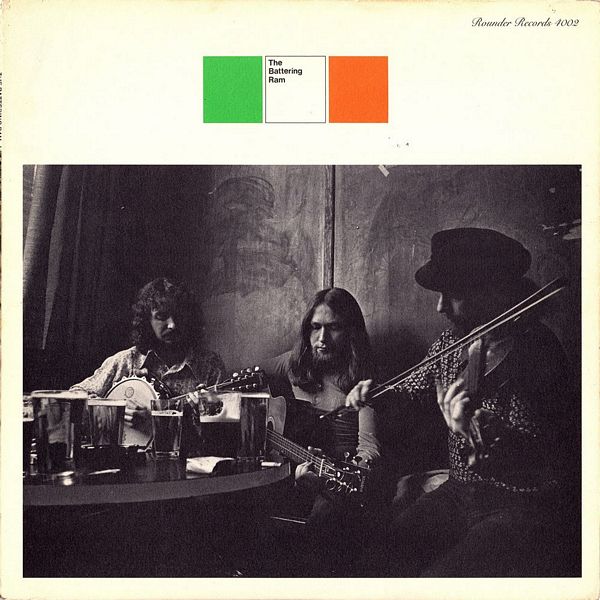

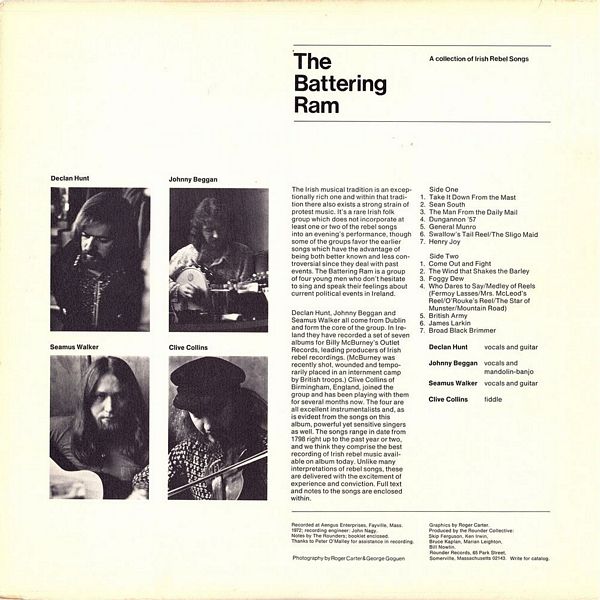

The Irish musical tradition is an exceptionally rich one and within that tradition there also exists a strong strain of protest music. It's a rare Irish folk group which does not incorporate at least one or two of the rebel songs into an evening's performance, though some of the groups favor the earlier songs which have the advantage of being both better known and less controversial since they deal with past events. The Battering Ram is a group of four young men who don't hesitate to sing and speak their feelings about current political events in Ireland.

Declan Hunt, Johnny Beggan and Seamus Walker all come from Dublin and form the core of the group. In Ireland they have recorded a set of seven albums for Billy McBurney's Outlet Records, leading producers of Irish rebel recordings. (McBurney was recently shot, wounded and temporarily placed in an internment camp, by British troops.) Clive Collins of Birmingham, England, joined the group and has been playing with them for several months now. The four are all excellent instrumentalists and, as is evident from the songs on this album, powerful yet sensitive singers as well. The songs range in date from 1798 right up to the past year or two, and we think they comprise the best recording of Irish rebel music available on album today. Unlike many interpretations of rebel songs, these are delivered with the excitement of experience and conviction. Full text and notes to the songs are enclosed within.

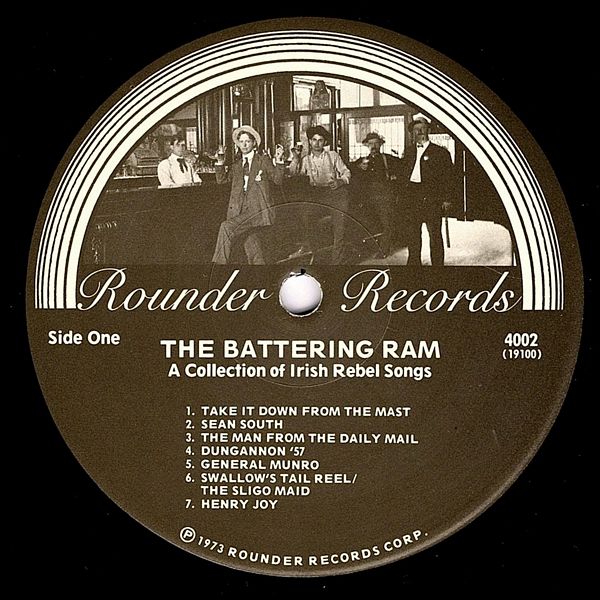

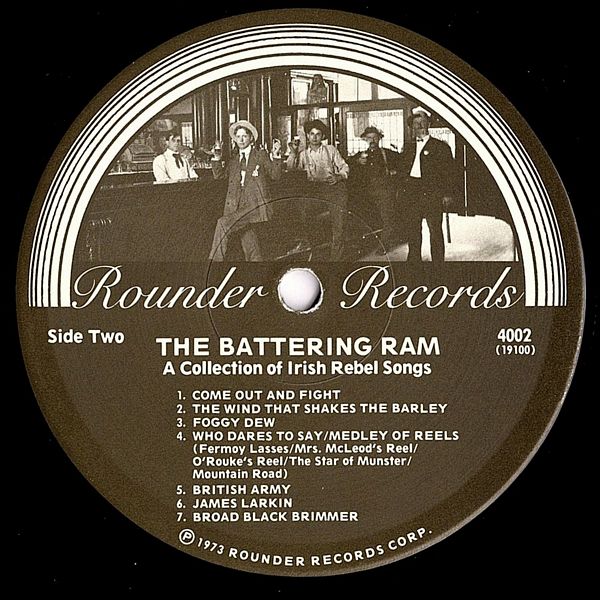

The Songs:

TAKE IT DOWN FROM THE MAST

You have murdered our brave Liam and Rory [1]

You have butchered young Richard and Joe

And your hands with their blood are still gory

Fulfilling the work of the foe.

Refrain:

So take it down from the mast, Irish traitors,

It's the flag we Republicans claim.

It can never belong to Free Staters,

For you've brought on it nothing but shame.

Then leave it to those who are willing

To uphold it in war and in peace,

To those men who intend to do killing

Until England's tyranny cease.

Refrain

We'll stand by Daly and Larkin

By the Provisionals and Sullivan the Bold [2]

And we'll break down the English connections

And we'll win back the nation you sold.

Refrain

You sold out the Six Counties for your freedom

When we have" given you McCracken and Wolfe Tone [3]

And brave Ulstermen have fought for you in Dublin

Now you watch as we fight on alone.

Refrain

And up in Ulster we're fighting on for freedom

For our people they yearn to be free

You executed those men who fought for us

With a hangman from over the sea.

Refrain

Repeat first stanza

Refrain

SeáN SOUTH [4]

It was on a dreary New Year's Day

As the shades of night hang down

A lorry load of volunteers

Approached the border town.

There was men from Dublin and from Cork,

Fermanagh and Tyrone,

But the leader was a Limerick lad,

Seán South of Garryowen.

And as they marched along the streets

Up to the barracks door

When they found the danger they would meet,

The fate that lay in store,

They were fighting for old Ireland's cause

To claim their very own,

But their leader was a Limerick man,

Seán South of Garryowen.

But the sergeant spoiled their daring plans;

He spied them through the door.

With the Sten guns and the rifles

A hail of death did pour.

And when that awful night had passed

Two men lay cold as stone

There was one from near the border

And one from Garryowen.

May God reward those gallant men

May Heaven be their home.

'Twas in Brookeborough town

Where they got shot down

In a cabin they lay cold.

Well, they never feared the RUC [5]

Or B-Men on patrol [6]

O'Hanlon from the border And South from Garryowen.

No more he will hear the seagulls cry

Or the Shannon's murmuring tide

For he fell beneath the Northern sky,

Brave O'Hanlon at his side.

He is bound to join that gallant band

Of Plunkett, Pearse, and Tone [7]

A martyr for old Ireland

Seán South of Garryowen.

THE MAN FROM THE DAILY MAIL

Oh, Ireland is a very funny place, sir,

It's a strange and a troubled land.

Oh, the Irish are a very funny race, sir,

Every girl's in Cumann Na mBan. [8]

Every doggy has a tri-colored ribbon

Tied firmly to its tail

And I wouldn't be surprising

If there'd be another rising

Said the man from the Daily Mail [9]

Refrain:

Every bird, upon my word,

Is singing treble, "I'm a rebel."

Every hen and jay, they're laying hand grenades

Over there, sir, I declare, sir.

And every cock in the farmyard stock

Is crowing for the Gael.

And I wouldn't be surprising

If there'd be another rising

Said the man from the Daily Mail.

Oh, the other day I traveled down to Clare, sir,

And I spied in an old boreen [10]

Such a bunch of Fenians there, sir, [11]

Dressed in orange, white, and green.

They were marching to the German goosestep

And whistling "Granuaile" [12]

Oh, I'm shaking in me shoes

As I'm sending out the news

Said the man from the Daily Mail.

Refrain

Oh, the country is seething with sedition

It's Sinn Fein through and through

All the people they are joining the Provisionals [13]

And the password's "Sinn Fein", too. [14]

The I.R.A. has sent me a time bomb in the mail

So be Jasus and begorrah

I'll be gettin' out tomorrow

Said the man from the Daily Mail.

Refrain

Repeat first stanza

Refrain

DUNGANNON '57

Some men went to Dungannon town [15]

The barracks for to case

And notice how the Queen's army

Gave class to that new place.

Refrain:

With your I.R.A., ricochet, play it on your Lambeg drum [16]

The R.U.C. they knew that we

Had planned to have some sport

For they'd read a piece of our police

In the Free State news report.

Refrain

The R.U.C. had read the news

And said, "Well, now, that's that."

When suddenly to their surprise

There came a rat-tat-tat.

Refrain

Well, what's goin' on out there, they said,

Now come and stop this lark.

Are you Protestants or Fenian men

That's out there in the dark?

Refrain

An R.U.C. man went outside

Came right in again

When he found that he was looking down

The barrel of a Sten.

Refrain

They blew the barracks up that night

And the R.U.C. as well

And if the British soldiers came, they said,

They'd blow them all to Hell.

Refrain

There are ten loyal policemen now

They're signing on the dole

And they'd love to get those Irish bastards

And shove it up his hole.

Refrain

GENERAL MUNRO

My name is George Campbell; at the age of eighteen

I joined the Unitedmen to strive for the green.

And many is the battle I did undergo

With our hero commander, brave General Munro. [17]

Have you heard of the battle of Ballynahinch

When the people, oppressed, they rose up in defense?

When Munro left the mountains, his men took the field

And they fought for twelve hours and never did yield.

Munro being tired and in want of his sleep

Gave a woman ten guineas his secret to keep.

When she had the money, the Devil tempted her soul;

She sent for the soldiers and surrendered Munro.

The soldiers they came and surrounded the place

And they took him to Lisburn and they lodged him in jail

And his father and mother is passing that way

Heard the very last words that their dear son did say.

"I'll die for my country as I've fought for her cause

And I don't fear her soldiers nor yet heed your laws."

And let every true man who hates Ireland's foe

Fight bravely for freedom like Henry Munro.

'Twas early next morning when the sun was still low

They murdered our hero, brave General Munro,

And high o'er the courthouse stuck his head on a spear

For to make the Unitedmen tremble with fear.

Up came Munro's sister, she was all dressed in green,

With a sword by her side that was well-sharped and keen,

Saying "God save old Ireland" and away she did go, baying,

"I'll have revenge for my brother Munro."

Oh you good men who listen, just think of the fate

Of our heroes who died in the year '98

For Ireland your nation would be free long ago

If her sons were all rebels like Henry Munro.

HENRY JOY [18]

An Ulsterman I'm proud to be

From the Antrim Glens I come

And though I labor by the sea

I have followed flag and drum.

I have heard the martial tramp of men,

I've seen men fight and die.

And as to Eire, I remember when

I followed Henry Joy.

I pulled my boat in from the sea

And I hid my sails away.

I put my nets under a tree

And I scanned the moonlit bay.

The boys were out, the Redcoats, too,

I kissed my wife goodbye.

And there beneath that greenwood shade

I followed Henry Joy.

Well we fought for Ireland's glory then

For home and shire we bled

Though our numbers few, our hearts beat true

And five to one lay dead.

Aye, and many a mother mourned her lad

And many a man his boy,

For youth was strong in that gallant throng

That followed Henry Joy.

In Belfast town they built a tree

And the Redcoats mustered there

I heard him come and the beating of the drum

Did sound o'er the barracks square.

He kissed his sister, went aloft,

And said a sad goodbye.

And as he died, I turned and I cried

You have murdered Henry Joy.

COME OUT AND FIGHT

I was born in a Dublin street where the loyal drums did beat

And the loving English feet, they tramped all over us,

And every single night as me father came home tight,

He'd invite the neighbors outside with this chorus:

Refrain:

Come, out ye Black and Tans [19]

Come out and fight me like a man.

Show your wife how you won medals down in Flanders.

Tell them how the I.R.A. made you run like Hell away

From the green and lovely lanes of Killeshandra.

Come let me hear you tell how you slammed the brave Parnell [20]

When you thought him truly well and persecuted.

Where are the sneers and jeers that you bravely let us hear

When our leaders of '16 were executed.

Allen, Larkin, and O'Brien, [21] how you bravely call them swine,

Robert Emmet, who you hung and drew and quartered. [22]

High upon the scaffold high how you murdered Henry Joy

And our Croppy Boys in Wexford you did slaughter. [23]

Refrain

Well, the day is coming fast and the time is nearly past

When each shoneen will be cast aside before us [24]

And if there be a need, then me kids will say Godspeed

With a bar or two of Stephen Behan's chorus.

Refrain

THE WIND THAT SHAKES THE BARLEY [25]

I sat within the valley green

I sat me with my true love

My sad heart strove to choose between

The old love and the new love.

The old for her, the new that made me

Think of Ireland dearly

While soft the wind blew down the glen,

And shook the golden barley.

How hard the bitter words to frame

To break the ties that bound us

But harder still to bear the shame

Of foreign chains around us.

And so I said, the mountain glen

I'll seek at morning early

And join the brave Unitedmen

While soft wind shakes the barley.

How sad I kissed away her tears

Her soft arms round me clinging

When suddenly the foe men shot

From out of wild woods ringing.

The bullet pierced my tru love's heart

In life's young spring so early

And on my breast in blood she died

While soft winds shook the barley.

But blood for blood without remorse

I'll take at Oulart Hollow [26]

And I have lain her grey cold corpse

Where I full soon must follow.

As round her grave I wandered drear

Night, noon, and morning early,

With breaking heart when e'er

I hear The wind that shakes the barley.

FOGGY DEW [27]

As down the glen one Easter morn

To a city fair rode I

There armored lines of marching men

In squadrons passed me by.

No pipes did hum; the battle drum

Did sound its loud tattoo

And the Angelus bell

O'er the Liffey Swell

Rang out in the foggy dew.

But the bravest fell

And the Requiem bell

Rang mournfully and clear

For those who died at Eastertime

In the springtime of the year.

And the world did gaze, with deep amaze,

At those fearless men but few

Who bore the fight, that freedom's light

Might shine through the foggy dew.

But the night was black, and the rifle's crack

Made perfidious Albion reel.

'Neath the leaden rain

Several tongues of flame

Did burn o'er the lines of steel.

And by each shining blade

A prayer was said

That to Ireland our sons would be true

And when morning broke

Still the war flag shook

Its' folds in the foggy dew.

It was England bade our wild geese go

That small nations might be free

But their lonely graves

Are by Suvla's waves

O'er the fringe of the gray North Sea.

O, had they died by Pearse's side,

Or fought with Connolly, too,

Then their graves we would keep

Where the Fenians sleep

'Neath the shrouds of the foggy dew.

Back to the glen I rode again;

My heart with grief was sore.

For I parted then with valiant men

I will never see no more.

As to and fro

In my dreams I go

And I kneel and I pray for you

When slavery fled all you rebel dead

When you fell in the foggy dew.

WHO DARES TO SAY [28]

Who dares to say forget the past

To men of Irish birth?

Who dares to say cease fighting

For our place upon this earth?

Let remembrance be our watchword

And our dead we'll never fail.

Let their graves be to us as milestones

On that blood-soaked one-way trail.

Remember how Owen Roe fought,

Leinster Mill beside. [29]

No man can say a coward fell

When Hugh O'Donnell died. [30]

Remember Ruth and Sarsfield [31]

And forget whoever will

That glorious stand at Limerick

At Kill McCadden hill. [32]

How Emmet's gallant handful

In historic Dublin town

Came out to give their challenge

To the forces of the Crown.

And then for a time, 'twas silence

Was Ireland's struggle done?

The answer's in the negative

Thundered manv a Fenian gun.

And then when England thought she'd won,

That we at last were meek,

Roared forth the glorious challenge

Of the men of Easter Week.

Remember how our soldiers fought

The scum of many lands.

Fought the scum of British prisons

And Britain's Black and Tans.

And then, by men we trusted,

This land of ours was sold;

They sold their friends to enemies

As Judas did of old.

Remember how in Kerry

They butchered our lads like swine. [33]

God, think of Ballyseedy,

Where they tied them to a mine.

How Rory and Liam and Dick and Joe,

To glut the imperial beast,

Were murdered while in prison

On our Blessed Lady's Feast.

How with overworked revolver

As he dashed from that hotel

Roared a rebel's last defiance

As Cathal Brugha fell. [34]

Hear we not the voice of Connolly,

The worker's soldier friend?

The conquered soul asserts itself

And we shall rise again.

For freedom, yes, and not to starve,

And not for rocks and clay;

But for the lives of Ireland's working class

We fight and die today.

And what, says Cathal Brugha,

If the last man is on the ground,

If he's lying weak and helpless

And his enemies ring him 'round;

If he's fired his last bullet,

If he's fired his final shot,

And they say, "Come into the Empire."

He should answer, "I will NOT."

Then back, back to that one-way trail

Ni Siochan Go Saoirse is the war cry of the Gael. [35]

While our country stands beside us

With the blood of martyrs set

Wayside crosses to remind us,

Who dares to say forget?

While Emmet's tomb is uninscribed

Until we our rights assert;

Until our country takes her place

Among the nations of the earth.

BRITISH ARMY [36]

When I was young I had a twist

For punching babies with me fist

And then I thought I would enlist

And join the British Army.

Refrain:

Oh too ra loo ra loo ra loo

They're looking for monkeys up in the zoo

And if I had a face like you

I'd join the British Army.

When I was young I used to be

As fine a lad as ever you'd see

And the Prince of Wales, he says to me,

"Come join the British Army."

Refrain

Corporal Daly went away

He left his sweet in the family way

And the only thing that she could say

Was "Blame the British Army."

Refrain

Ian Paisley has the drought.

Fill him up with Guinness's stout

He'll beat the enemy with his mouth

And save the British Army.

Refrain

We beat the enemy without fuss

And leave their bones out in the dust

I know for they quite near beat us

The gallant British Army.

Refrain

So if you're young and in your prime

And fond of every kind of crime

I promise you a jolly good time

Inside the British Army.

Too ra loo ra loo ra loo

I've made me mind up what to do

Well, I'll work me ticket home to you

And I'd fuck the British Army.

JAMES LARKIN [37]

In Dublin city in 1913

The boss was boss and the poor were slaves,

The women working and the children hungry,

Then on came Larkin like a might wave.

The workmen cringed when the bossman thundered

And just ten hours was his weekly chore

He asked for little and less was granted

Thus getting little he would ask for more.

Then God sent Larkin, so dark and handsome,

A might man with a mighty tongue,

The voice of justice, the voice of labor,

And he was gifted and he was young.

And God sent Larkin, in 1913,

A mighty man with a mighty tongue,

He raised the workers, he gave them courage;

He was their leader, a worker's son.

In the month of August the bossman told us

No union man for him could work.

We stood for Larkin, we told the bossman,

We'd fight or die but we would not shirk.

Eight months we fought and eight months we starved

We stood by Larkin through thick and thin.

But foodless homes and the crying of children,

They broke our hearts and we could not win.

Then Larkin left us, we seemed defeated,

The night was dark for the working man.

Along came Connolly with hope and counsel

His motto was that we'd rise again.

In Dublin city, in 1916,

The English soldiers, they burned the town.

They shelled the buildings, they shot our leaders.

Their heart was buried beneath the Crown.

They shot MacDermott and Pearse and Plunkett,

They shot MacDonagh and Clarke the brave [38]

From bleak Kilmainham they took their bodies

To Arbour Hill and a quick lime grave. [39]

And last of all our seven heroes

I'll sing the praise of James Connolly.

The voice of justice, the voice of freedom,

Who gave his life that men might be free.

BROAD BLACK BRIMMER [40]

There's a uniform hanging in what's known as father's room,

A uniform so simple in its style.

It has no braid of silk nor gold, no hat with feathered plume,

Yet me mother has preserved it all the while.

One day she made me try it on, a wish of mine for years,

"Just in memory of your father, Seán," she said.

And as I tried the Sam Brown on she was smiling through her tears

And she placed the broad black brimmer on me head.

Refrain:

It's just a broad, black brimmer,

Its ribbons frayed and torn

By the carelessness of many's the mountains breeze,

An old trench coat that's all battle-stained and worn

And the britches almost threadbare at the knees.

A Sam Brown belt with a buckle big and strong

And a holster that's been empty many the day.

Oh, when men claim Ireland's freedom,

The one they'll choose the lead 'em

Will wear the broad black brimmer of the I.R.A.

That uniform was worn by me father long ago

When he reached me mother's homestead on the run;

That uniform was worn in that little church below

When Father Mac, he blessed the pair as one.

Then after truce and treaty and the parting of the ways

He wore it as he marched out with the rest,

And as they bore his body down the rugged heather braes,

They placed the broad black brimmer on his breast.

Refrain

Repeat first stanza

Refrain

An understanding of the crisis in Ireland today is not possible unless one comprehends the following statement by G. Desmond Greaves: "The conflict is not between two sets of discriminators, but between those who want to divide the people and those who want to unite them." [41] The question of religion is not merely a smokescreen, However. It has deep historic roots in the days when English colonizers asserted and established power over the native peoples of Ireland. The natives were Catholic; the waves of English and Scottish settlers were Protestant. "If the setting were Algiers, rather than Belfast, the differences of skin color would lead us immediately to identify racism as the core of the problem. But in the Irish setting, religious affiliation, rather than skin color, has marked the social identities of the two groups, colonizers and colonized. This crucial difference has obscured the mechanisms at work and confused many outside observers. Our thoughts move too quickly to the Catholic Church and its viciously reactionary institutional role in places like Spain and Latin America, to allow us to understand what it means for an Irishman to think of himself as a Catholic ," [42] Conor Cruise O'Brien, writing in the New York Review of Books, elaborates,

Basically, religious affiliation was-and is- socially, economically, and politically significant, for it distinguishes, with very few exceptions, the natives and their children from the 17th century settlers and their children. The British Crown, in the post-Reformation period, naturally favored the settlement of loyal Protestants, and the dispossession of natives, whose support of the Counter-Reformation was necessarily a form of rebellion: politics and religion were inseparable from the start.

The Protestant settlers-Scotch and English- were the gainers, the Catholic natives were the losers: antagonistic collective interests were established immediately. The natives were dispossessed, but not exterminated nor assimilated nor converted to Protestantism. Their Catholicism became the badge of their identity and their defiance. After the destruction of the Gaelic social order by the end of the 17th Century and the substitution of English for the Gaelic language-a process completed by the mid 19th century-the Catholic Church became almost the sole form of social cohesion of the native people. [43]

Nevertheless, those who have fought for Irish freedom have always stressed religious toleration. Wolfe Tone, Henry Joy McCracken, and Henry Munro, and the United Irishmen of 1798 exemplify this truth. So does the Easter Week proclamation. As do the contemporary activities of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (WICRA) and many other groups. The I.R.A. has always adopted this position, as have essentially all Republican groups. From time to time, of course, there have been instances of sectarian fighting, hardly surprising in light of the numerous provocations. There has never been a Catholic association devoted to the abolition of Protestantism, while there have been several groups (such as Paisley's) organized against Catholicism. The tricolor flag with its green and orange symbolizes the desire for unity.

"Religious sectarianism originated not in Ireland but in Britain, whose revolution was fought under the slogans of the Reformation. The final expropriation of the Irish tribal lands proceeded under the only excuse which would justify naked robbery to the British people. This was protection against the papacy, for practical purposes enshrined not in the spiritual power of Rome, but in the military designs of Spain and France… Ireland from 1782 to 1800 had legislative independence. But only Protestants could vote or sit in Parliament, which thus became the central executive committee of the landlord class… (Wolfe Tone's) proposal was to enfranchise the Catholics when inevitably landlordism would be swept away, Ireland undergoing a revolution similar to that of France. Rather than face such a prospect, the landlords fell in with the British oligarchy in submerging the Irish representation in Westminster through the Act of Union." [45]

The partition of Ireland was designed to prevent a united, revolutionary Ireland. It had become apparent over the years that the Act of Union was not working and that the Irish would incessantly fight to be free. The English ruling class and the landlord class of Northern Ireland shared the fear of a socialist republic in Ireland, for obvious reasons. Trade union solidarity between English and Irish workers, as indicated in British workers' support of the 1913 strike of the Dublin Transport Workers, made revolutionary contagion a real threat in England as well. Thus, rather than allow full independence for all of Ireland, the ruling classes cleverly partitioned Ireland into two different zones. Greaves feels that stifling revolution was the primary reason. English imperialism also stood to gain in other ways. The Free State lost 29 % of its population, the main industrial areas, the largest port, and 40 % of the taxable capacity of the country as the Six Counties were brought under the control of Westminster. (The Stormont parliament in Ulster has control overonly 10 % of tax revenues, and has almost no real power at all. Any doubts as to the degree of Ulster independence from Westminster were erased by the stationing of British troops in the Six Counties. Currently the occupying force numbers around 25,000.) With the loss of the industrial areas, the 26 counties were faced with a severely unfavorable balance of trade, and the need for machinery and equipment. Two things resulted: over-reliance on agriculture and the cattle industry (the most socially backward elements of the, society) and the necessity to admit foreign investments, thus-resulting in a classically neo-colonial situation in the Free State while the Six Counties of Ulster remain fundamentally colonial. Greaves quotes Brian O'Neill as observing the start of the process forty years ago: "Landlordism has been replaced by Bondlordism." [46]

It has become popular in recent years to refer to Ireland as "Britain's Vietnam" and the parallels are obvious. The unity of British and American imperialism was dramatically demonstrated b the recent July 1972 invasion of citizen-controlled areas by over 20,000 British troops. The following day William Whitelaw, British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, publicly thanked President Richard Nixon on the floor of the House of Commons. "Without President Nixon's permission, Whitelaw explained, the British could not have abandoned their N.A.T.O. commitments to send extra troops to Northern Ireland… without the extra troops the invasion could not have been carried out. Whitelaw wanted to take this opportunity, he said, 'to thank our American allies.' He assured the Members of Parliament that President Nixon has been fully briefed on 'Operation Motorman1 in advance of the event." [47]

Jack Lynch, Prime Minister of the Republic of Ireland also knew. This provides further ammunition, of course, for the sentiments embodied here in the song "Take It Down From the Mast." It has been said that "the founders of the Irish Free State were men of petit-bourgeois origin, who out of fear of its ultimate logic allowed themselves to become the agency of halting a popular revolution, thus handing power to the bourgeoisie." [48] The Prime.Minister has a nephew, Captain Lynch of the British First Paratroop Battalion, which as of August 1972 occupied the Ballymurphy section of Belfast. [49]

The objection is often raised that a united Ireland would simply reverse the pattern of discrimination, with the Ulster Protestants being placed in the minority. Britain partitioned Ireland, the Irish people did not. By arbitrarily cutting the country into two parts, and both building a gerrymander onto and encouraging traditional social cleavages, the British essentially gave a minority the "power of veto on the unity of Ireland." There is no doubt that if the will of the people of all 32 counties had been expressed that the majority would have overwhelmingly voted for complete independence from England. So essentially a minority of the people were given majority control in a section of the country, though nothing more than a simple gerrymander created in collusion between the wealthy elements in Northern Ireland and their stooges and the Westminster Parliament in London. The question is one of democracy: are the Irish people as a whole to be allowed to settle their own affairs by majority rule, or does Britain retain the right to divide, partition, and enforce dependency? Again, the military occupation in Northern Ireland leaves no doubt as to how they see it.

The movement for a united Ireland takes the form of civil rights agitation in both North and South-in the South there currently is resistance to bourgeois rule, evidenced in a series of rent strikes and workers control agitation. After a two-month occupation of their factory at Navan, the workers of Crarmac Teo have formed a cooperative and purchased the plant from the liquidators. In the North, the celebrated "no-go areas" were living examples of citizens government until the British invasion and reoccupation of July. The widespread refusal to pay gas and electric bills continues.

The tragedy of division in the Republican ranks continues, and the differences of opinion between the Official and Provisional wings have at times exploded into fightings and even killings. It's a characteristic feature of revolutionary movements that they often dissipate more time fighting other factions than the real enemy. Feelings run deep, though, as the Officials accuse the Provisionals of indiscriminate terroristic bombing alienating the great majority of the people from the Republican cause and certainly doing a great deal to eliminate any possibility of united Protestant and Catholic action. The United Irishman calls the Provisional leader "Mad Jack" MacStiofain and criticizes them for meeting with Whitelaw. "For even while Seán MacStiofain's boys were liberating working people's arms and legs from their bodies, while the internees languished in Long Kesh, another sell-out was being arranged… The only tangible result of all the Provisionals' actions has been an increase in sectarian tensions almost to the point of civil war, a seat for Mad Jack at the sell-out table, many deaths and widespread confusion amongst the people as to what was going on." [51]

Writing from such a distance as we are, it is difficult to comment much further. The Provisionals may deserve credit for carrying the struggle to a more active stage than civil rights marches, yet it does seem as though they must be held responsible for a degeneration of the struggle as described above. Obviously the future of Ireland rests in the capacity of the Republican ranks to somehow close, and also for people in other lands to exert pressure on the British.' The English working class can play the strongest role here', but persons of all classes in America and elsewhere must add their weight as well.

The Battering Ram's songs present a fairly consistent statement, though members of the group are admittedly not thoroughly political in their orientation. As noted above, they have mixed Officials songs with Lyrics talking of "joining the Provisionals." They have played in both an Official and. a Provisional club on the same evening. They probably are closer in personal sympathies to the Provisionals and say that if it wasn't for them, the struggle might not exist today. (As may have been clear, we tend to favor the Official I.R.A. interpretation of the situation.) But while the Battering Ram have not attempted to work out a consistent political philosophy for themselves, they have and are quite evidently contributing greatly to the cause they all believe in. Johnny explains that they have never been in the I.R.A. as they just do not have the required discipline-the I.R.A, is a 24-hour-a-day calling. One must be ready at any moment to follow directives in a disciplined fashion. Constant drilling and political education are important, as are the missions, both offensive and defensive, for which members must be ready at all times.