|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

The Singers

LOUIS KILLEN, born at Gateshead-on-Tyne in 1934, comes from a singing family. He worked at various jobs before becoming a full-time singer and a student of folk-music, particularly of the north-east. He has sung all over this country at clubs, and on radio and television. Now living in the United States, he has spent most of his life on Tyneside, where in 1958 he founded the still flourishing Newcastle club, 'Folksong and Ballad'. His repertoire, which once contained much American material, is now mainly British, and although a skilled player on several instruments he now prefers the native concertina.

JOHNNY HANDLE is the pseudonym of a former mine-worker, born at Wallsend in 1935, who lives in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. His main musical interest was formerly in jazz, and as a folk-singer he began with a repertoire of blues and American songs, gradually going over to British, especially north-eastern, material, including his own songs. These were inspired by a study of A. L. Lloyd's Come All Ye Bold Miners and other collections of mining songs. Two or three years ago he left the pits, where he had become a mining surveyor, and is now a teacher. He is still very active as a singer, in the clubs — he helped to found the Newcastle club, of which he is a resident singer — and has sung on radio and television.

The Accompanist

COLIN ROSS, born at North Shields, where he still lives, in 1934, is a sculptor and teacher, who has long played for morris, sword and country dance teams, in this country and on tours abroad. He joined 'Folk Song and Ballad', of which he is still resident musician, in 1961. His fiddle playing has a strong, vigorous style, based on that of the best Border fiddlers, and he is an almost equally skilled performer on the Northumbrian pipes, tin whistle and melodeon. His music is used not only for accompanying singers and dancers, but also for solo and consort playing.

The Songs

Mining songs first. These are among the oldest (and the newest) of those sung today in Northumberland and Durham. Consider the dates of first publication, so far as these can be traced. (The words of most songs appeared in print long before the melodies). The riotous Collier's Rant was printed in 1793, but seems, in its description of a fight with the Devil in the dark of the mine, to echo a much more distant past. The Waggoner (Doon the Waggon-Way) may be almost as old ; first printed, apparently, in 1812, it is a woman's love-song, half-way in style between a country and an industrial song. It is roughly dated by the archaic means of transporting coal which it describes. Up the Raw, also found in John Bell's book of 1812, although a dandling song, sounds the harsher note, not entirely absent from The Waggoner, which is characteristic of north-eastern song, especially at this early period. The Blackleg Miners, anonymous, like these four and unlike the songs to be mentioned, although first noted, with its tune, in 1949, was born perhaps a hundred years earlier. In these four songs many of the characteristics of the miner are apparent: the pride in his work; the boisterous enjoyment of leisure; the sense of a closed community; the stoicism; the superstition; the humour; the habit of rough banter towards a loved one, oddly mixed, sometimes, with tenderness; the savagery towards enemies.

With the local compositions, the work of Anderson, Barrass and Armstrong, pitman-poets and part-time stage-singers of the eighteen-seventies, eighties and nineties, comes a certain change: the humour is less fierce; sentimentalism enters; the pit-work is described in greater technical detail. The pride, and many of the other older characteristics remain. Aw Wish Pay Friday Wad Come jokes wryly about the hardships which beset a miner's home when a fortnight's pay is lost in gambling, while The Putter, humorous too, is one of a series in which Alexander Barrass describes the different kinds of mining work. The Trimdon Grange Explosion, on the other hand, is written in the manner of a disaster song: pathetic, formal in language, and without the dialect words which writers of local compositions usually love to provide.

Johnny Handle's pieces, belonging to the mid-twentieth century and the age of the second folk-song revival — that which centres round the clubs — maintain the music-hall tradition, with omissions and additions appropriate to their period. They avoid the sententious vein of some of the older songs and show little of the discontent which we find in such songs as The Blackleg Miners, where the miner expressed his resentment against blackleg labour, and, by implication, the mine-owners. The wealth of technical detail continues, and there is still much about the miner's diversions, on Friday evenings at the pub, and on summer outings to 'the Coast'. Less familiar are the backward look, from a calmer period, at the days of struggle when the 'unions came to be', and, in Farewell to the Monty, the mingled feelings of regret and relief at a familiar twentieth-century happening, a pit-closure. Of Johnny's songs there are no doubt more to come.

Some of the remaining songs recorded here — those not concerned with mining — also seem old. They include two of the very best Northumbrian songs. Sair Fyeld Hinny, printed in a slightly different version in 1784, but very likely older, is a grave lament for lost youth, a rarity in folk-song, while Dollia, printed in 1812, is a skit, apparently of the seventeen-nineties, but perhaps just remade at that time, against the soldier-mad girls of the town. The Anti-Gallican, referring to an event of 1779, must have arisen about that date, while Derwentwater's Lament, if written, as it probably was, by Robert Surtees, presumably dates from about 1820. These two may be regarded as local compositions, although the author of the one is unknown and of the other uncertain. Joe Wilson's well-known comic song, Keep Your Feet Still, Geordie Hinny, is a local composition of much later date, about 1870.

The tunes of the older anonymous songs recorded here are, so far as we know and with the exception of The Blackleg Miners, their own. The local compositions of the nineteenth century and earlier, like most songs of this type, are set to borrowed tunes, but the Handle texts are set to tunes written specially for the purpose by Johnny himself, alone or in collaboration. The Trimdon Grange Explosion, has had an experience not uncommon among this class of song : it has changed the tune to which it was originally sung (The Cottage by the Sea) for another, which is modal, less sentimental, and more to the taste of the present day, when sung to words like these.

Variation has been at work on all these songs, local compositions of known authorship included. Small changes — some, it may be presumed, introduced not much before the present recording — can be seen both in the texts by Surtees and the other writers, and in the anonymous verses of The Collier's Rant and The Blackleg Miners, white Johnny Handle varies his own words, as other singers may do after him. Tunes are varied too: The Trimdon Grange Explosion, for example, as sung here, differs slightly from the air noted in 1951.

We know little about how these songs were accompanied in earlier times, although it is said that the Northumbrian small-pipes were sometimes used. Singing may often have been unaccompanied, but in the Newcastle music-halls, and in the mechanics' halls of the pit-villages, no doubt three-piece bands or piano backed the singer, and the later appearance of piano editions must have encouraged home singing round the family upright. Concert singers of a higher social class than, say, Joe Wilson, and choral societies, singing in parts, would also have a piano accompaniment. No piano is heard on this record. The guitar or banjo is used for some songs, while instruments longer established, for varying periods, in British tradition — fiddle, tin whistle, concertina and melodeon — accompany others. The small-pipes, particularly associated with Northumbria, are used for yet another group, either alone or with another instrument. Combinations of instruments are used for four songs. Four are sung unaccompanied.

All these songs are peculiar to the north-east, in the sense that — with the exception of a variant of The Blackleg Miners — they seem not to occur in closely similar form in collections made elsewhere. Folksongs are rarely so narrowly distributed — local compositions are another matter — and it may be that variants, at any rate of the older songs, existed once in other countries, but escaped collection and disappeared. Collection began earlier in Northumberland and Durham than in most parts of England.

It must be remembered that the people of the north-east never confined their singing to 'Northumbrian songs', such as those recorded here. The local collections themselves contain many versions of songs well known elsewhere, such as The Seeds of Love and Green Broom, while it has been possible to collect locally, in the last few years, other songs equally famous, such as The Banks of the Sweet Dundee and Died of Love, from singers who had them from a line of earlier north-easterners.

The Anti-Gallican Privateer — Text printed by Bell, 1812. The Anti-Gallican, of Newcastle, sailed from Shields, March 6th, 1779. The song, which describes the hopes of profit people had from a privateer fitted out during the American War of Independence, was evidently composed before the ship's return, for the Anti-Gallican took no prize.

The Collier's Rant — Text printed by Joseph Ritson, Northumberland Garland, 1793. One of the oldest English mining songs. The rant was a seventeenth-century dance.

Up The Raw — Text printed by Bell, 1812. A dandling song. The raw is eveidently a pit-row — a 'row of colliery houses.

Farewell To The Monty — The early part of 1959 marked the closing of a number of pits in the Northumberland coalfield. One of them, the Montague Colliery, West Denton, Newcastle on Tyne, was closed over a long period of time, its men being shifted gradually to pits on the eastern, coastal part of the field. Johnny Handle worked in this pit for a period during his apprenticeship. He wrote this song, on the pit's closure, in January, 1959.

The Blackleg Miners — Text printed in Come All Ye Bold Miners. A Northumberland pit-song collected by A. L. Lloyd from W. Sampey, Bishop Auckland, Co. Durham, in 1949. Reprisals against blacklegs were common during the strikes of the last century in the Northumbrian coalfield, when the owners brought in Welsh, Irish and Cornish labour, in attempts to break the miner's union. A variant of this song has been noted in Nova Scotia.

The Collier Lad (The Filler) — This is the first song about mining which Johnny Handle wrote. It is about the productive man of the mine, the filler. Fillers spent the best part of their working lives lying on their sides shovelling the loosened coal on to the conveyor belt. By reputation they have great thirsts which can be quenched only by large quantities of beer.

Dol-Li-A — Text printed by Bell, 1812. The Black and Green Cuffs were two regiments stationed in Newcastle in the early 1790s.

The Waggoner — Text printed by Bell, 1812. Another tune is in W. G. Whittaker's North Countrie Ballads, Songs and Pipe-Tunes, 1921. Carting coal along light surface railways is work that went out when the steam locomotive came in.

Derwentwater's Farewell — Appeared in Hogg's Jacobite Relics, 1819-21, to whose editor it was supplied by Robert Surtees, the probable author of the verses. The tune, Never Love Thee More, had already been used for a number of songs. It is popular among players of the small-nines.

Stottin' Doon The Waall — This song describes the activities of the young single men working at the Rising Sun Colliery, Wallsend, Northumberland, at the week-end after drawing their pay. The Waall in the song is the wall of R. Hood Haggie's Rope Works, which runs from the centre of Wallsend (just behind the High Street) up into the housing estates between the town centre and the Sun Colliery. It was the habit of one of the pit's apprentice surveyors, after a good night's drinking and dancing and seeing a girl home, to place his shoulder against the top end of this wall (he was usually inebriated) and bounce his way along it, knowing that when the wall came to an end he'd be in the centre of the town, where he lived.

Keep Your Feet Still, Geordie Hinny — Words by Joe Wilson, 1841-73, famous Tyneside music-hall writer and performer. It ranks, with Ridley's Blaydon Races and Cushie Butterfield, among the best known Tyneside music-hall songs.

The Stone Man's Song — This song is about the men who advance the tunnels near the coal face. They move up the coal removing machines, and the conveyors draw out the props in the area from which coal has recently been removed (the goaf) and replace them in new positions close to the face, allowing the roof to collapse behind them. This is a highly dangerous job which is done when the rest of the work in the pit has ceased, usually on the night shift (4 p. m. - 10 p. m.), hence the term 'no man's land', for there are very few people, other than the stonemen, underground.

Aw Wish Pay Friday Wad Come — Words written, 1870, by James Anderson, miner, of Elswick, Newcastle.

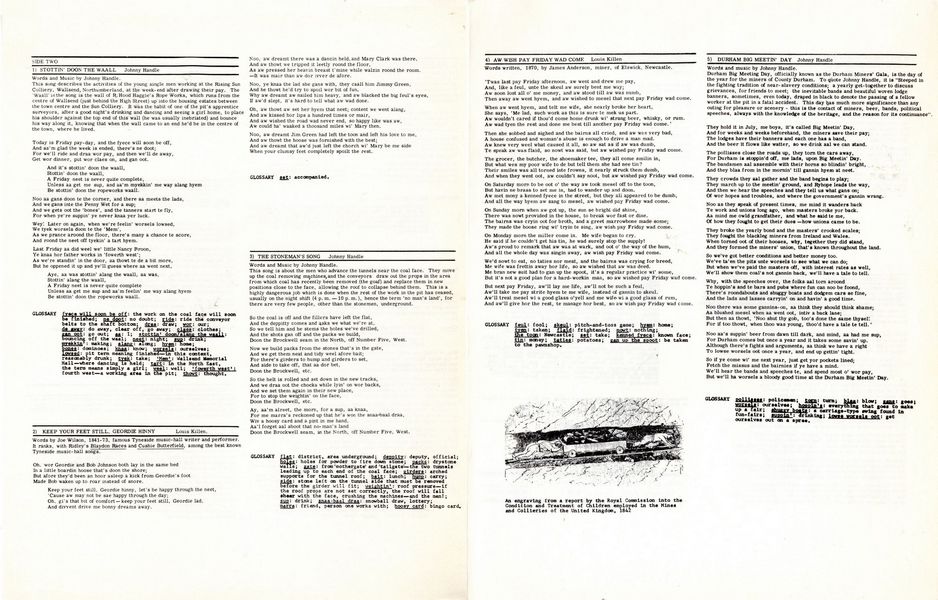

Durham Big Meetin' Day — Durham Big Meeting Day, officially known as the Durham Miners' Gala, is the day of the year for the miners of County Durham. To quote Johnny Handle, it is "Steeped in the fighting tradition of near-slavery conditions; a yearly get-together to discuss grievances, for friends to meet; the inevitable bands and beautiful woven lodge banners, sometimes, even today, draped in black to denote the passing of a fellow worker at the pit in a fatal accident. This day has much more significance than any outing for pleasure or scenery — this is the contact of miners, beer, bands, political speeches, always with the knowledge of the heritage, and the reason for its continuance".

The Trimdon Grange Explosion — Words by Thomas Armstrong, pitman-poet, written in 1882, immediately after the explosion, in which seventy-four lives were lost. This version is substantially the same as that noted, with the present tune, by A. L. Lloyd, in 1951. Originally set to the tune of Go and Leave Me If You Wish It. (The Cottage By The Sea).

The Putter — Words by Alexander Barrass, pitman-poet, and included in his Pitman's Social Neet, 1897. Originally sung to the tune of Wait for the Waggon. The present tune is by Johnny Handle. A putter is a miner who takes the tubs from the fillers to the shaft-bottom. The tubs are drawn up in groups of forty-one, and each of the putters working together in one section always strives to be the one who gets the odd tub, since the pay is by the tub. This song tells the troubles of a putter who is working in a bad section, full of obstructions which slow him down.

Sair Fyel'd, Hinny — A different version of the words was printed by Joseph Ritson in Gammer Gurton's Garland, 1784.