|

Sleeve Notes

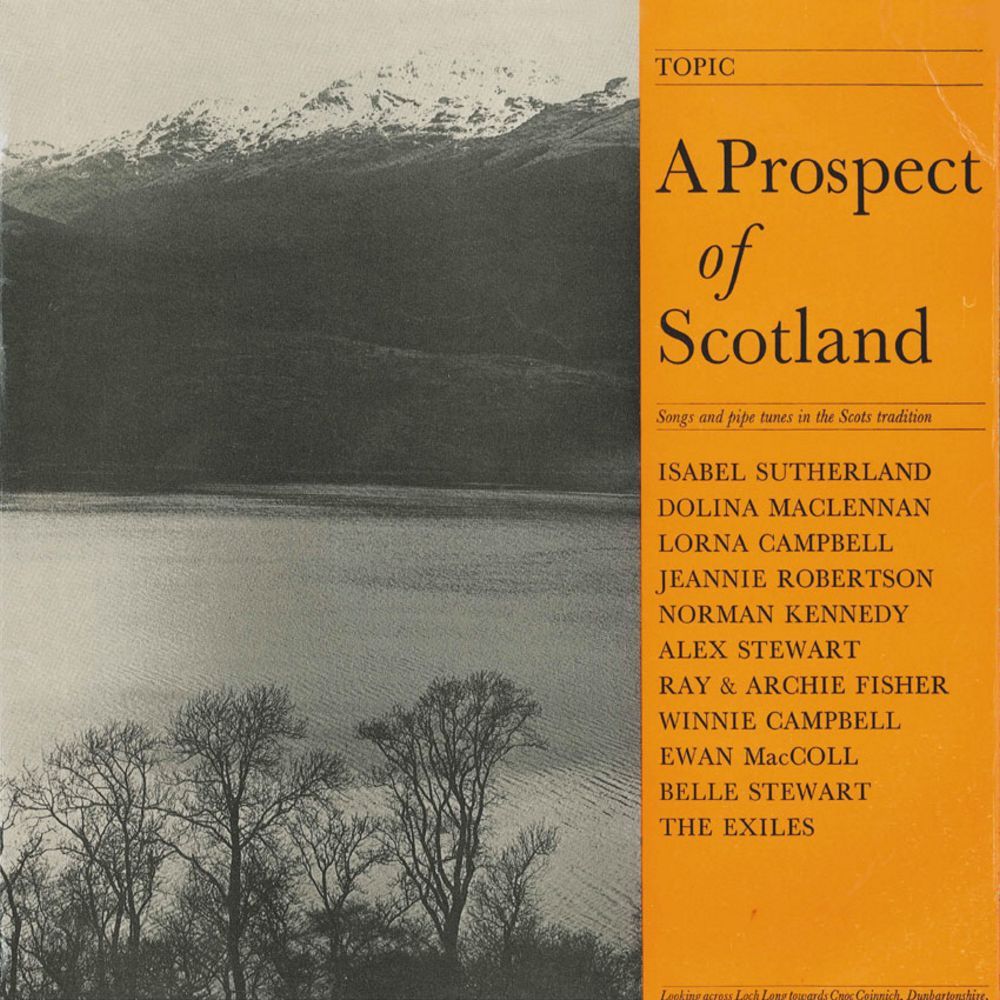

Scotland the brave. Land of mists, heather and tartan; of porridge, venison and amber coloured whisky. The Scotland of the travel posters tends also to be the picture of his native land the exile takes with him to the four corners of the earth. Or to England. Where he will sigh for lakes, mountains and the skirl o' the pipe, exotically romanticised by time and distance.

And maybe he will quite forget the real flavour of Scotland, which is stern, ribald and rational all at once. The towns have harsh, forbidding stone faces although the countryside is so beautiful it wins the heart immediately. But the Clyde is for building ships, Lanarkshire is for mining, and Scotland contains some of the blackest, bleakest industrial slums in Europe as well as so much physical beauty.

A physical beauty which itself is often the price of depopulation. Bracken usurps the homesteads. Sheep nibble where the fiddler used to play for reels and flings. The drift away from the country, the drift away from Scotland, is relentless.

Who built Scotland's character? All sorts of people. John Knox, arch puritan, furious foe of licentiousness and frivolity. And also, parodoxically, Robert Burns, poet, radical and lover. David Hume, too, chief architect of the Age of Reason, who lived in eighteenth century Edinburgh, the Athens of the North. Sir Walter Scott, who put Scotland squarely into the Romantic period, tartan and all, and helped make popular the glory of her traditional balladry.

For the visitor, life is full of pleasant surprises. They serve you crisp, hot, delicious rolls for breakfast and call a leg of lamb a "gigot" as if they were pretending to be French, a relic of the "auld alliance", in the days long before the union with England, when Scotland and France presented a united front from two directions against that country. And Edinburgh rock, which sounds as grim as granite, turns out to be confectionery, crumbly in texture and almost excessively sweet. This something like the Scots temperament, which is not nearly so stern as it is painted. The legendary dourness of the race, on examination, is seen to be no grimness but a stoic courage, no dourness but passionate convictions intensely held.

Not till the tenth century was the name "Scotland" applied to the country north of the Cheviots, and, in that century, the dialect of English that now seems to us to be the authentic voice of Scotland began to supersede the native Gaelic.

So modern Scots is really an importation from the north of England all the time. In fact, all through

the Middle Ages, the lowland Scot called his speech not "Scots" but English-"Scots" to him always meant Gaelic.

On this record of the music of Caledonia, Dolina Maclennan sings in Scots Gaelic and Lorna Campbell sings a song translated into English from that language, nowadays spoken more freely in Scots settlements in the New World than in the Old. The Fisher family have a song in English, Joy of my Heart, a fine Gaelic tune, and the process has been reversed—its lyric praising the beauty of the Western Isles has lately been translated back into Gaelic.

During the Middle Ages and for a long time afterwards, the division between the Gaelic Highlands and the English Lowlands was a very real one. The bare-legged Highlander, garbed in plaids, slept on bundles of heather, fished, hunted and plundered cattle from the hard-working Lowlanders, who could not understand a word their wild countrymen spoke and were already living in towns and founding industries, like God-fearing people.

The Highlanders were tribal, clansmen bound in loyalty to their chief, living roughly in rough country, accepting no authority but the chief and largely dependent on him for their livelihood. By the end of the Middle Ages, English-speaking Scotland was a self-respecting member of the European community of nations but there always remained in the blue distance these natives who seemed like foreigners.

Despite the illusory bond of language, Scotland and England fought like cat and dog until 1603, when James, the son of ill-fated Mary, Queen of Scots, became the sixth king of that name in Scotland and the first king of that name in England. One prince united the nations; strife, it would seem, was at an end.

But the evil fortunes of the House of Stewart willy nilly involved the land from which they came. When the Stewarts were turned peremptorily off the throne at the end of the seventeenth century and left to wander disconsolate through Europe, the old-fashioned, feudal Highlands still supported the Jacobite cause and paid the price in blood. The Lowlands, already profiting from union with England and fiercely Protestant, into the bargain, wanted no more of the autocratic, Catholic Stewart line.

But the Stewarts were loved in Scotland. The tragic Jacobite cause is reflected on this record in Isabel Sutherland's song, King Fareweel, a song she says "has always seemed to me to be like a bugle call or a battle cry." And after the defeat of the famous Jacobite rebellion in 1745, the Highlands were crucified and the Lowlands prospered.

In the heart of the rural North East, there were prosperous farms that hired a multitude of farm servants and housed them in stone built huts or "bothies". This practice continued until our own day. During the long winter evenings, these bothies were the scene of much music making and we call the songs associated with them "bothy ballads".

There are two favourite such ballads on this record—Sleepy-toon, finely sung by Norman Kennedy, and Bogie's Bonnie Belle, sung by Winnie Campbell. This last is a story of love gone sour told with all the wry honesty of the Scots. This record brings the musical history right up to the factories and mills of the industrial revolution, too; Ray Fisher sings a graphic and lively industrial piece, The Spinner's Wedding.

Ray Fisher is a young woman who has consciously learned her way of singing from that of the great Scots women singers. Two of these singers, and they are two of the finest singers you could wish to hear, appear on this record. Both are of the "Travelling" or tinker stock and both have a way with a song to melt the stoniest heart.

Jeannie Robertson, sometimes called "the greatest ballad singer in the world", is represented by a salty slice of underworld life, the broadside ballad, The Bonny Wee Lassie who Never said No, and Belle Stewart performs one of the masterpieces of Scots balladry, The Dowie Dens of Yarrow.

The traditional ballads of Scotland, dating perhaps from Medieval times, perhaps before, are one of the great, though anonymous, glories of Scots literature. Ewan MacColl sings another great ballad, Minorie, also called The Two Sisters, widely known in England and America, too, and believed to be of Scandinavian origin, relic of the constant intercourse between Scotland and Scandinavia over the centuries.

You can hear, too, the savage but noble sound of the Highland war pipes, the most famous bagpipes of all, played by Alex Stewart, husband of Belle; and the record closes, fittingly, with a song by Robert Burns, Scotland's finest poet and one of the most warmly human and utterly human men who ever lived, A Man's A Man for A' That.

This record is Scotland in little, a brief glance at her history, a quick look at the fabric of Scots life. Here we have some small but tangible and genuine a part of Caledonia herself.