|

|

Sleeve Notes

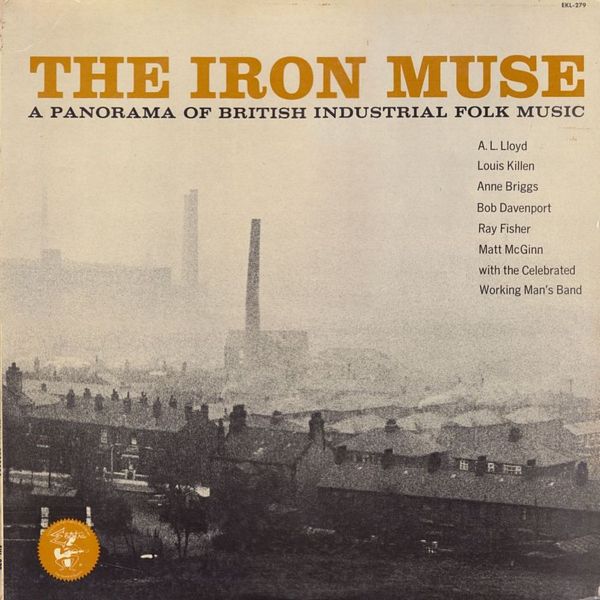

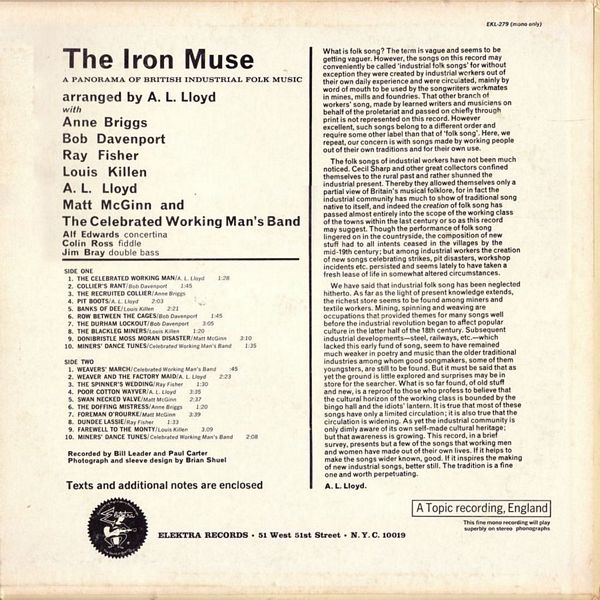

What is folk song? The term is vague and seems to be getting vaguer. However, the songs on this record may conveniently be called 'industrial folk songs' for without exception they were created by industrial workers out of their own daily experience and were circulated, mainly by word of mouth to be used by the songwriters workmates in mines, mills and foundries. That other branch of workers' song, made by learned writers and musicians on behalf of the proletariat and passed on chiefly through print is not represented on this record. However excellent, such songs belong to a different order and require some other label than that of 'folk song'. Here, we repeat, our concern is with songs made by working people out of their own traditions and for their own use.

The folk songs of industrial workers have not been much noticed. Cecil Sharp and other great collectors confined themselves to the rural past and rather shunned the industrial present. Thereby they allowed themselves only a partial view of Britain's musical folklore, for in fact the industrial community has much to show of traditional song native to itself, and indeed the creation of folk song has passed almost entirely into the scope of the working class of the towns within the last century or so as this record may suggest. Though the performance of folk song lingered on in the countryside, the composition of new stuff had to all intents ceased in the villages by the mid-19th century; but among industrial workers the creation of new songs celebrating strikes, pit disasters, workshop incidents etc. persisted and seems lately to have taken a fresh lease of life in somewhat altered circumstances.

We have said that industrial folk song has been neglected hitherto. As far as the light of present knowledge extends, the richest store seems to be found among miners and textile workers. Mining, spinning and weaving are occupations that provided themes for many songs well before the industrial revolution began to affect popular culture in the latter half of the 18th century. Subsequent industrial developments—steel, railways, etc.—which lacked this early fund of song, seem to have remained much weaker in poetry and music than the older traditional industries among whom good songmakers, some of them youngsters, are still to be found. But it must be said that as yet the ground is little explored and surprises may be in store for the searcher. What is so far found, of old stuff and new, is a reproof to those who profess to believe that the cultural horizon of the working class is bounded by the bingo hall and the idiots' lantern. It is true that most of these songs have only a limited circulation; it is also true that the circulation is widening. As yet the industrial community is only dimly aware of its own self-made cultural heritage; but that awareness is growing. This record, in a brief survey, presents but a few of the songs that working men and women have made out of their own lives. If it helps to make the songs wider known, good. If it inspires the making of new industrial songs, better still. The tradition is a fine one and worth perpetuating.

A. L. Lloyd