|

|

|

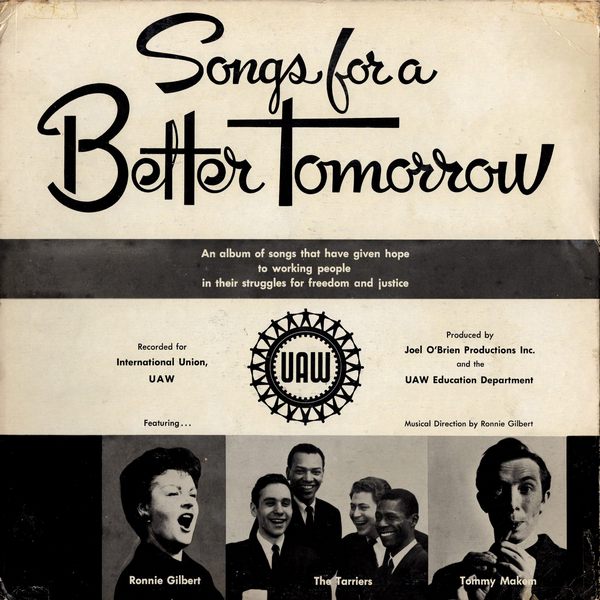

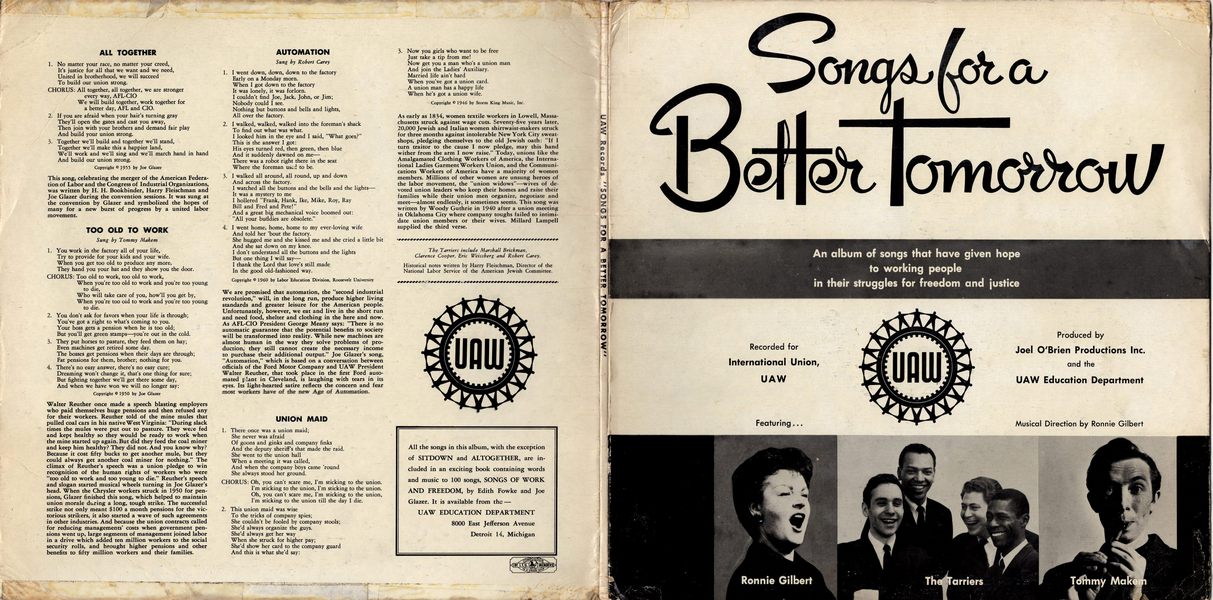

An album of songs that have given hope to working people in their struggles for freedom and justice.

Sleeve Notes

Joe Hill — In 1901, a young Swede, Joel Emanuel Hagglund, emigrated to the United States at the age of nineteen. He worked at odd jobs, mined copper, worked on the docks of California, shipped out as a sailor on the Honolulu run, and worked in the wheat fields. He changed his name to Joe Hill somewhere along the line and joined the Industrial Workers of the World, the IWW or Wobblies, in 1910. A militant industrial unionist, he was always "scribbling" songs, some of which became labor classics, like "Casey Jones — the Union Scab," and "The Preacher and the Slave." He was arrested on a murder charge in Salt Lake City, and despite vigorous protests by the American Federation of Labor, workers throughout the world, the Swedish government, and the intervention of President Woodrow Wilson, was shot by a five-man firing squad on November 19, 1915. The day before his execution, he wired Wobbly leader Big Bill Haywood, "Don't waste time mourning. Organize." The night before he was shot, a speaker at a protest meeting in Salt Lake City cried: "Joe Hill will never die!" This moving song by Earl Robinson and Alfred Hayes, written twenty years after his death, helps keep his memory alive as a symbol of all those killed while struggling for labor's rights.

Solidarity Forever — This is the most popular union song in America. Written in 1915 by poet Ralph Chaplin, an organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World, the idea came to him while helping coal miners in the Kanawha Valley strike in West Virginia. His defiant, militant lyrics combined with the stirring march rhythm of the Civil War tune, "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," have made this song the anthem of the American labor movement and a favorite on picket lines and at union meetings throughout the nation.

No Irish Need Apply — America has long been the Golden Land of opportunity to millions of poverty-stricken immigrants, who were eagerly recruited to fill the insatiable maws of a growing economic system. Frequently, however, the economic machine creaked and went into a depression. Then the immigrants who came looking for work found themselves low man on the totem pole. Their color, nationality or religion were used to bar them from jobs. The barrier of discrimination has been used in this country at various times against Irish, Jews, Poles, Chinese, Italians and many others. In recent years, those hardest hit have been Negroes and Latin Americans. This song stems from the time of the Irish potato famines of 1845-47 when thousands of Irishmen fled their starving country. In America, signs were soon posted, "No Irish Need Apply," and this song was written to express the resentment of Irish workers and their militancy, which is not unlike the militancy of the young people in the sit-in and integration movements today.

The Mill Was Made Of Marble — In 1947, textile workers in North Carolina lost a five-month strike for a sixty-five cents an hour minimum wage at the Safie Textile Mill. Before it ended, an old striker brought Margaret (Pat) Knight of the union staff a tattered sheet of paper with eight lines about a "mill built of marble." When she showed the words to Joe Glazer, he reworked it, added several verses and, with Pat Knight, set it to music. Though written in 1947, the song symbolizes the heartbreak of workers in an industry with a 150-year-long, unhappy history of low wages, long hours, child labor, stretch-out and speed-up, and company-dominated mill towns.

Which Side Are You On? — In 1931, Harlan County, Kentucky coal miners were on strike. Mountaineer miners fought back hard against armed company deputies who beat, shot and killed union leaders. During the strike, Sheriff J. H. Blair came to the home of union leader Sam Reece while his wife, Florence, was there with their seven children. Failing to find Sam, the sheriff's force kept watch outside, ready to shoot Sam if he returned. This incident inspired Mrs. Reece to write the words to this song, which has since been adapted by workers for use in many other strikes. It dramatized the kind of class war that existed in America in the depression years.

Roll The Union On — Written at an Arkansas labor school in 1936, this song soon became popular with the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union. A Negro sharecropper and union organizer, John Handcox, wrote the first verse, and Lee Hays added others. Based on a gospel hymn, "Roll the Chariot On," the unionist merely substituted "boss" for "Devil" and "union" for "chariot" and another labor hit was on its way. The song became very popular and was the favorite of Alan Haywood, the CIO's chief organizer, who died in 1953.

We Shall Not Be Moved — During a strike of the West Virginia Mine Workers Union in 1931, 106 families living in company homes were evicted one morning. The League for Industrial Democracy and Brookwood Labor College were conducting a Labor Chautauqua for the union, and Mrs. Ethel Clyde, a philanthropist who had given the L.I.D. money for its educational work among the miners, was shocked at the sight of the miners and their children sleeping in an open field, without even tents to shelter them. She put up money for rent so that the miners could get back into their homes. That night, jubilation reigned supreme. A choir of Negro union members started to sing new verses to an old hymn, "We Shall Not Be Moved." They started out with:

"The people of New York have decided — We shall not be moved.

"Just like a tree that's planted by the water, We shall not be moved."

Sit Down! — In 1936 and 1937, General Motors' strikers developed one of labor's most dramatic weapons in the struggle for industrial organization — the sit-down strike. Auto workers laid down their tools, but instead of going out on strike, physically took possession of the plant to prevent the company from moving equipment to another factory or moving in scabs — either of which developments might well have broken the strike. The GM sit-downs led a veritable wave of organizing strikes and sparked the growth not only of the Congress of Industrial Organizations but of many American Federation of Labor unions as well. During the auto sit-downs, the United Auto Workers union maintained excellent discipline in the plants, sanitary squads kept them spic and span, and the union carried on educational classes and organized choruses and bands.

UAW-CIO — Author John Gunther has called the United Auto Workers, now part of the AFL-CIO, "the most volcanic union in the country." With more than a million members, it has pioneered in such collective bargaining fields as pensions, cost-of-living increases, supplemental unemployment benefits (SUB), and regular productivity wage increases. Before America entered World War II, Walter Reuther proposed a dramatic plan to convert the auto plants to produce 500 planes a day — a plan ridiculed by the industry. In a short time, Reuther's basic concept was adopted and production zoomed to 100,000 planes a year. During the war, UAW members (and unionists in steel, rubber, glass, electrical and scores of other industries) mass-produced armadas of planes, jeeps and tanks which rolled the war on to victory against the Nazis and their allies. This song was written by Bess and Baldwin Hawes.

Song Of The Guaranteed Wage — "The saddest object in civilization," said Robert Louis Stevenson, "and the greatest confession of its failure, is the man who can work and wants to work, and is not allowed to work." Of course that's not what people who try to sell the nation on so-called "Right-to-Work" laws are talking about. They just want to wreck unions. But unions have been concerned for the past century and a half about recurring cycles of panics, booms and depressions that have plagued our economy. In addition to pushing for full employment legislation, unions have struggled both for unemployment insurance and then for guaranteed annual wages. In 1955, the United Auto Workers carried on a campaign which culminated in a contract with the Ford Motor Company, calling for a form of the guaranteed annual wage, under the term "supplemental unemployment benefits." Soon after, unions in steel, rubber, glass and other industries won similar guarantees in their contracts. Just before the 1955 convention, Ruby McDonald, the talented wife of a Flint auto worker, sent Joe Glazer "a song on the guaranteed annual wage," which he sang to the cheers of 2,500 convention delegates.

All Together — This song, celebrating the merger of the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations, was written by H. H. Bookbinder, Harry Fleischman and Joe Glazer during the convention sessions. It was sung at the convention by Glazer and symbolized the hopes of many for a new burst of progress by a united labor movement.

Too Old To Work — Walter Reuther once made a speech blasting employers who paid themselves huge pensions and then refused any for their workers. Reuther told of the mine mules that pulled coal cars in his native West Virginia: "During slack times the mules were put out to pasture. They were fed and kept healthy so they would be ready to work when the mine started up again. But did they feed the coal miner and keep him healthy? They did not. And you know why? Because it cost fifty bucks to get another mule, but they could always get another coal miner for nothing." The climax of Reuther's speech was a union pledge to win recognition of the human rights of workers who were "too old to work and too young to die." Reuther's speech and slogan started musical wheels turning in Joe Glazer's head. When the Chrysler workers struck in 1950 for pensions, Glazer finished this song, which helped to maintain union morale during a long, tough strike. The successful strike not only meant $100 a month pensions for the victorious strikers, it also started a wave of such agreements in other industries. And because the union contracts called for reducing managements' costs when government pensions went up, large segments of management joined labor in a drive which added ten million workers to the social security rolls, and brought higher pensions and other benefits to fifty million workers and their families.

Automation — We are promised that automation, the "second industrial revolution," will, in the long run, produce higher living standards and greater leisure for the American people. Unfortunately, however, we eat and live in the short run and need food, shelter and clothing in the here and now. As AFL-CIO President George Meany says: "There is no automatic guarantee that the potential benefits to society will be transformed into reality. While new machines are almost human in the way they solve problems of production, they still cannot create the necessary income to purchase their additional output." Joe Glazer's song, "Automation," which is based on a conversation between officials of the Ford Motor Company and UAW President Walter Reuther, that took place in the first Ford automated plant in Cleveland, is laughing with tears in its eyes. Its light-hearted satire reflects the concern and fear most workers have of the new Age of Automation.

Union Maid — As early as 1834, women textile workers in Lowell, Massachusetts struck against wage cuts. Seventy-five years later, 20,000 Jewish and Italian women shirtwaist-makers struck for three months against intolerable New York City sweatshops, pledging themselves to the old Jewish oath: "If I turn traitor to the cause I now pledge, may this hand wither from the arm I now raise." Today, unions like the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, and the Communications Workers of America have a majority of women members. Millions of other women are unsung heroes of the labor movement, the "union widows" — wives of devoted union leaders who keep their homes and raise their families while their union men organize, negotiate and meet — almost endlessly, it sometimes seems. This song was written by Woody Guthrie in 1940 after a union meeting in Oklahoma City where company toughs failed to intimidate union members or their wives. Millard Lampell supplied the third verse.