|

|

|

|

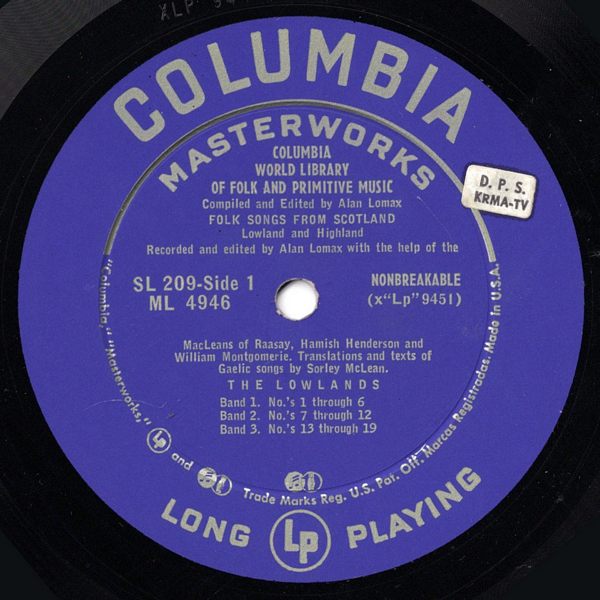

Introduction

What most impressed me on my collecting trip to Scotland in the summer of 1951 was the vigor of the Scots folk singing tradition, on the one hand, and its close connection with literary sources on the other. I could give scores of incidents that illustrate this. In a byre in South Uist a rawboned Hebridean woman sang three milking croons to make her cow give more milk. The first she knew was by a modern Gaelic poet, the second she had learned in school and of the last, she said, "I do not think it has ever been printed." Yet in this district there still lives the finest tradition of work song singing in western Europe.

The Scots have the liveliest folk tradition of the British Isles, but paradoxically, it is the most bookish.

Everywhere in Scotland I collected songs of written or bookish origin from country singers, and, on the other hand, I constantly encountered bookish Scotsmen who had good traditional versions of the finest folk songs. For this reason I have published songs which show every degree and kind of literary influence.

Scots folksong is extraordinarily nationalistic, the result of the centuries of wars with England. On the other hand, the nation of Scotland is divided into two very different cultural halves — the Highlands especially the Hebrides, where Gaelic is still spoken and where there still survives the remnants of the high and beautiful Gaelic culture — and the Lowlands, where the British popular ballad is at its very best and many people speak Lalands, a vernacular felt by the Scots to be a distinct language from English. Both of these regions have been much affected by their religious history. For instance, in some regions of the Hebrides the Presbyterian Kirk absolutely and effectively forbids all dancing; and in neighboring Catholic Islands the kalays last till morning. So one never knows what mixture of shame, joy or pride in his folk culture one will encounter in a Scot, but, whether it is love of bagpipes, Burns or border ballads, there is certain to be great enthusiasm for some sort of folk music.

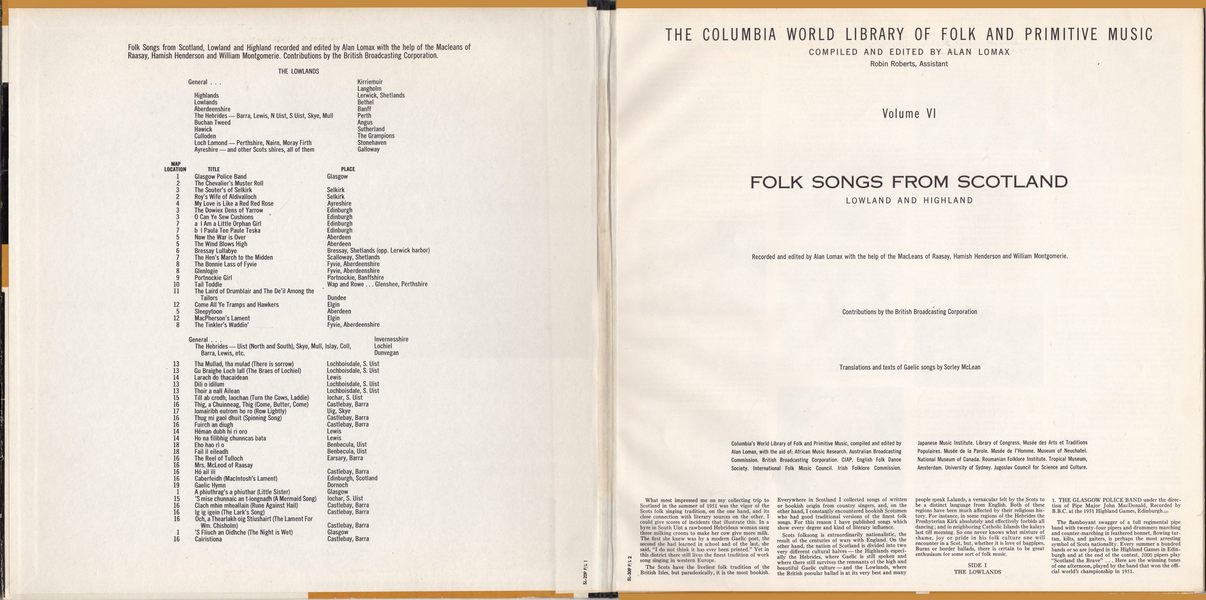

THE LOWLANDS

1. The Glasgow Police Band under the direction of Pipe Major John MacDonald, Recorded by B.B.C. at the 1951 Highland Games, Edinburgh.

The flamboyant swagger of a full regimental pipe band with twenty-four pipers and drummers marching and counter-marching in feathered bonnet, flowing tartan, kilts, and gaiters, is perhaps the most arresting symbol of Scots nationality. Every summer a hundred bands or so are judged in the Highland Games in Edinburgh and at the end of the contest, 2000 pipers play "Scotland the Brave" … Here are the winning tunes of one afternoon, played by the band that won the official world's championship in 1951.

2. The Chevaliers' Muster Roll, sung by Ewan McColl

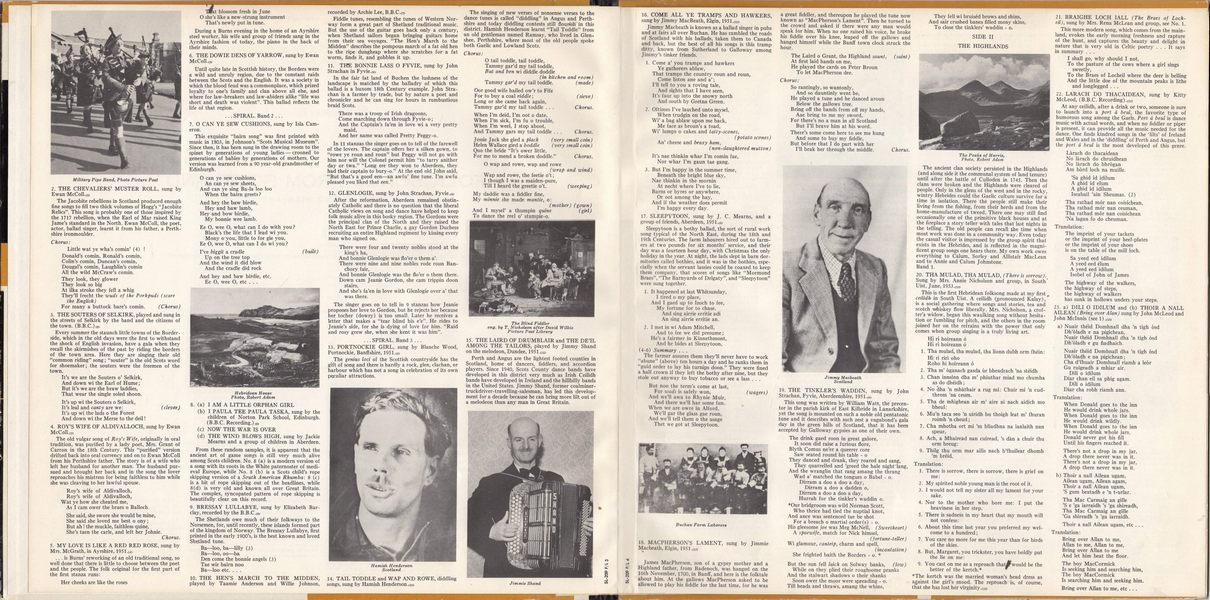

The Jacobite rebellions in Scotland produced enough fine songs to fill two thick volumes of Hogg's "Jacobite Relics". This song is probably one of those inspired by the 1717 rebellion, when the Earl of Mar raised King Jame's standard in the North. Ewan McColl, the poet, actor, ballad singer, learnt it from his father, a Perthshire ironmoulder.

3. The Souters Of Selkirk, played and sung in the streets of Selkirk by the band and the citizens of the town. (B.B.C.)

Every summer the staunch little towns of the Border-side, which in the old days were the first to withstand the shock of English invasion, have a gala when they recall the skirmishes of the past by riding the borders of the town area. Here they are singing their old "common riding" song; "souter" is the old Scots word for shoemaker; the souters were the freemen of the town.

4. Roy's Wife Of Aldivalloch, sung by Ewan McColl.

The old vulgar song of Roy's Wife, originally in oral tradition, was purified by a lady poet, Mrs. Grant of Carron in the 18th Century. This "purified" version drifted back into oral currency and on to Ewan McColl from his Perthshire father. The story is of a wife who left her husband for another man. The husband pursued and brought her back and in the song the lover reproaches his mistress for being faithless to him while she was cleaving to her lawful spouse.

5. My Love Is Like A Red Red Rose, sung by Mrs. McGrath, in Ayrshire, 1951.

… is Burns' reworking of an old traditional song, so well done that there is little to choose between the poet and the people.

6. The Dowie Dens Of Yarrow, sung by Ewan McColl.

Until quite late in Scottish history, the Borders were a wild and unruly region, due to the constant raids between the Scots and the English. It was a society in which the blood feud was a commonplace, which prized loyalty to one's family and clan above all else, and where for law-breakers and law-abiders alike "life was short and death was violent". This ballad reflects the life of that region.

7. O Can Ye Sew Cushions, sung by Isla Cameron.

This exquisite "bairn song" was first printed with music in 1803, in Johnson's "Scots Musical Museum". Since then, it has been sung in the drawing room to the spinet by generations of young ladies — crooned to generations of babies by generations of mothers. Our version was learned from a 90 year-old grandmother of Edinburgh.

8. I Am A Little Orphan Girl, etc.

a) I Am A Little Orphan Girl

b) I Paula Tee Paula Taska, sung by the children of Norton Park School, Edinburgh. (B.B.C. Recording.)

c) Now The War Is Over

d) The Wind Blows High, sung by Jackie Mearns and a group of children in Aberdeen.

From these random samples, it is apparent that the ancient art of game songs is still very much alive among Scots children. No. 8 (a) is a modern version of a song with its roots in the White paternoster of medieval Europe, while No. 8 (b) is a Scots child's rope skipping version of a South American Rhumba: 8 (c) is a bit of rope skipping out of the headlines, while 8(d) is very old and known all over Great Britain. The complex, syncopated pattern of rope skipping is beautifully clear on this record.

9. Bressay Lullabye, sung by Elizabeth Barclay, recorded by the B.B.C.

The Shetlands owe much of their folkways to the Norsemen, for, until recently, these islands formed part of the kingdom of Norway. The Bressay Lullabye, first printed in the early 1900's, is the best known and loved Shetland tune.

10. The Hen's March To The Midden, played by Taamie Anderson and Willie Johnson, recorded by Archie Lee, B.B.C.

Fiddle tunes, resembling the tunes of Western Norway form a great part of Shetland traditional music. But the use of the guitar goes back only a century, when Shetland sailors began bringing guitars home from their sea voyages. "The Hen's March to the Midden" describes the pompous march of a fat old hen to the ripe dungheap where she scratches for a fat worm, finds it, and gobbles it up.

11. The Bonnie Lass O Fyvie, sung by John Strachan in Fyvie.

In the fair fat land of Buchen the lushness of the landscape is matched by the balladry of which this ballad is a buxom 18th Century example. John Strachan is a farmer by trade, but by nature a poet and chronicler and he can sing for hours in rumbustious braid Scots.

In 11 stanzas the singer goes on to tell of the farewell of the lovers. The captain offers her a silken gown, to "rowe ye roun and roun" but Peggy will not go with him nor will the Colonel permit him "to tarry anither day or twa." "Long ere they won to Aberdeen, they had their captain to bury-o." At the end old John said, "But that's a good een—an awfu' fine tune. I'm awfu pleased you liked that een."

12. Glenlogie, sung by John Strachan, Fyvie.

After the reformation, Aberdeen remained obstinately Catholic and there is no question that the liberal Catholic views on song and dance have helped to keep folk music alive in this bosky region. The Gordons were the principal clan of the North and they raised the North East for Prince Charlie, a gay Gordon Duchess recruiting an entire Highland regiment by kissing every man who signed on.

The singer goes on to tell in 9 stanzas how Jeanie proposes her love to Gordon, but he rejects her because her tocher (dowry) is too small. Later he receives a letter that makes a "tear blind his e'e". He rides to Jeanie's side, for she is dying of love for him. "Raid and rosy grew she, when she kent it was him".

13. Portnockie Girl, sung by Blanche Wood, Portnockie, Banffshire, 1951.

The genius loci of the Scottish countryside has the gift of song and there is hardly a rock, glen, clachan, or harbour which has not a song in celebration of its own peculiar attractions.

14. Tail Toddle & Wap And Rowe, diddling songs, sung by Hamish Henderson.

The singing of new verses of nonsense verses to the dance tunes is called "diddling" in Angus and Perthshire and today diddling contests still flourish in this district. Hamish Henderson learnt "Tail Toddle" from an old gentleman named Ramsay, who lived in Glen, shee, Perthshire, where most of the old people spoke both Gaelic and Lowland Scots.

15. The Laird Of Drumblair & The De'il Among The Tailors, played by Jimmy Shand on the melodeon, Dundee, 1951.

Perth and Angus are the lightest footed counties in Scotland, home of dancers, fiddlers, and accordion players. Since 1940, Scots County dance bands have developed in this district very much as Irish Ceilidh bands have developed in Ireland and the hillbilly bands in the United States. Jimmy Shand, former coalminer-truckdriver-travelling-salesman, has led this development for a decade because he can bring more lilt out of a melodeon than any man in Great Britain.

16. Come All Ye Tramps And Hawkers, sung by Jimmy MacBeath, Elgin, 1951.

Jimmy Macbeath is known as a ballad singer in pubs and at fairs all over Buchan. He has rambled the roads of Scotland with his ballads, taken them to Canada and back, but the best of all his songs is this tramp ditty, known from Sutherland to Galloway among Jimmy's tinker friends.

17. Sleepytoon, sung by J. C. Mearns, and a group of friends, Aberdeen, 1951.

Sleepytoon is a bothy ballad, the sort of rural work song typical of the North East, during the 18th and 19th Centuries. The farm labourers hired out to farmers at two pounds for six months' service, and their day was a fourteen hour day, with Christmas the only holiday in the year. At night, the lads slept in barn dormitories called bothies, and it was in the bothies, especially when the servant lassies could be coaxed to keep them company, that scores of songs like "Mormond Braes", "The Barnyards of Delgaty", and "Sleepytoon" were sung together.

18. MacPherson's Lament, sung by Jimmie Macbeath, Elgin, 1951.

James MacPherson, son of a gypsy mother and a Highland father, from Badenoch, was hanged on the 16th November, 1700, in Banff, and here is the folktale about him. At the gallows MacPherson asked to be allowed to play his fiddle for the last time, for he was

a great fiddler, and thereupon he played the tune now known as "MacPherson's Lament". Then he turned to the crowd and asked if there were any man would speak for him. When no one raised his voice, he broke his fiddle over his knee, leaped off the gallows and hanged himself while the Banff town clock struck the hour.

19. The Tinkler's Waddin, sung by John Strachan, Fyvie, Aberdeenshire, 1951.

This song was written by William Watt, the precentor in the parish kirk of East Kilbride in Lanarkshire, yet the song is mounted on such a noble old pentatonic tune and it describes with such zest a vagabond's gala day in the green hills of Scotland, that it has been accepted by Galloway gypsies as one of their own.

THE HIGHLANDS

The ancient clan society persisted in the Highlands (and along side it the communal system of land tenure) until after the battle of Culloden in 1745. Then the clans were broken and the Highlands were cleared of people. Only in the glens of the west and in the rocky, wintry Hebrides could the Gaelic culture survive for a time in isolation. There the people still make their living from the fishing, from their herds and from the home-manufacture of tweed. There one may still find occasionally one of the primitive black houses and at the fireplace a story teller with tales that last nights in the telling. The old people can recall the time when most work was done in a community way. Even today the casual visitor is impressed by the group spirit that exists in the Hebrides, and is reflected in the magnificent group songs one hears there. My own work owes everything to Calum, Sorley and Allistair MacLean and to Annie and Calum Johnstone.

20. Tha Mulad, Tha Mulad, (There is sorrow). Sung by Mrs. Annie Nicholson and group, in South' Uist, June, 1953.

This is the first Hebridean folksong made at my first ceilidh in South Uist. A ceilidh (pronounced Kalay), is a social gathering where songs and stories, tea and scotch whiskey flow liberally. Mrs. Nicholson, a crofter's widow, began this waulking song without hesitation or fumbling for pitch, and the others in the room joined her on the refrains with the power that only comes when group singing is a truly living art.

21. Braighe Loch Iall (The Braes of Locked), sung by Mrs. Rena McLean and group, see No. 1.

This more modern song, which comes from the mainland, evokes the early morning freshness and rapture of the hunt, and captures the beauty and delight in nature that is very old in Celtic poetry … It says in summary …

22. Larach Do Thacaidean, sung by Kitty McLeod, (B.B.C. Recording).

At any ceilidh, after a drink or two, someone is sure to launch into a port a beul, the favorite type of humorous song among the Gaels. Port a beul is dance music with actual words, and when no fiddler or piper is present, it can provide all the music needed for the dance. One finds kindred songs in the 'lilts' of Ireland and Wales and in the 'diddling' of Perth and Angus, but the port á, beul is the most developed of this genre.

23. Dili O Idilum & Thoir A Nall Ailean (Bring over Alan) sung by John McLeod and John McInnis (see l).

24. Till Ab Crodh, Laochan, (Turn the Cows, Laddie), sung by Mrs. Kate Nicholson, Iochar, South Uist, June 1951.

During the great period of Gaelic folksong the basis of life in the Highlands was cattle. The Highland milkmaid had to be a singer, for the people had found that cattle respond to soothing songs and can differentiate between tunes, giving milk freely for some, witholding it for others. I recorded this milking song, at 11 p.m. on a white night of June in the byre of Mrs. Kate Nicholson as the milk flowed into the pail.

25. Thig, A Chuinneag, Thig (Come, Butter, Come) sung by Miss Annie Johnston while churning. Recorded in Barra, June 1951.

26. Iomairibh Eutrom Ho Ro (Row Lightly), Sung by Allan MacDonald, recorded in Uig on Skye, June, 1951.

From ancient times in the Hebrides, the rowing and the sailing of the clan galleys evoked heroic song, and, even after 1745, the dangers and joys of the sea continued to inspire Gaelic bards. In this rowing song, presumably, one of the rowers would sing the line and then his comrades would give the three line refrain. No Hebridean singer I questioned, however, could remember having heard a rowing song in actual use.

27. Thug Mi Gaol Dhuit, (Spinning Song) sung by Calum Johnston, Castlebay, Barra, June, 1951.

In the old days, an Island woman was known by the way she dressed her men against the cold and wet of his work in the mists and storms of the Minch. All the clothing was homemade and was the handiwork of the woman, from the carding of the wool to the final dressing of the cloth. Even today, the manufacture of tweeds is one of the staple industries of the islands.

This spinning song matches the peculiar rhythm of the spinner, with a long sustained phrase for spinning the thread away from the bobbin, while the spinner addresses the wheel and the thread in beautiful verses.

28. Fuirich An Diugh (Weaving Song), Sung by Annie Johnston, Castlebay, Barra, September 1951.

In this song, perhaps one discovers the ironic attitude of the weaver toward his painstaking work or, hears the echoes of some lost incantation.

Waulking Songs

29. Héman Dubh Hi Rì Oro, from Lewis. (B.B.C. Recording)

30. Hó Na Filibhig Chunncas Báta, from Lewis (B.B.C. Recording)

31. Eho Hao Ri Ó, from Benbecula, recorded June, 1951.

32. Fail Il Éileadh, from Benbecula, recorded June 1951.

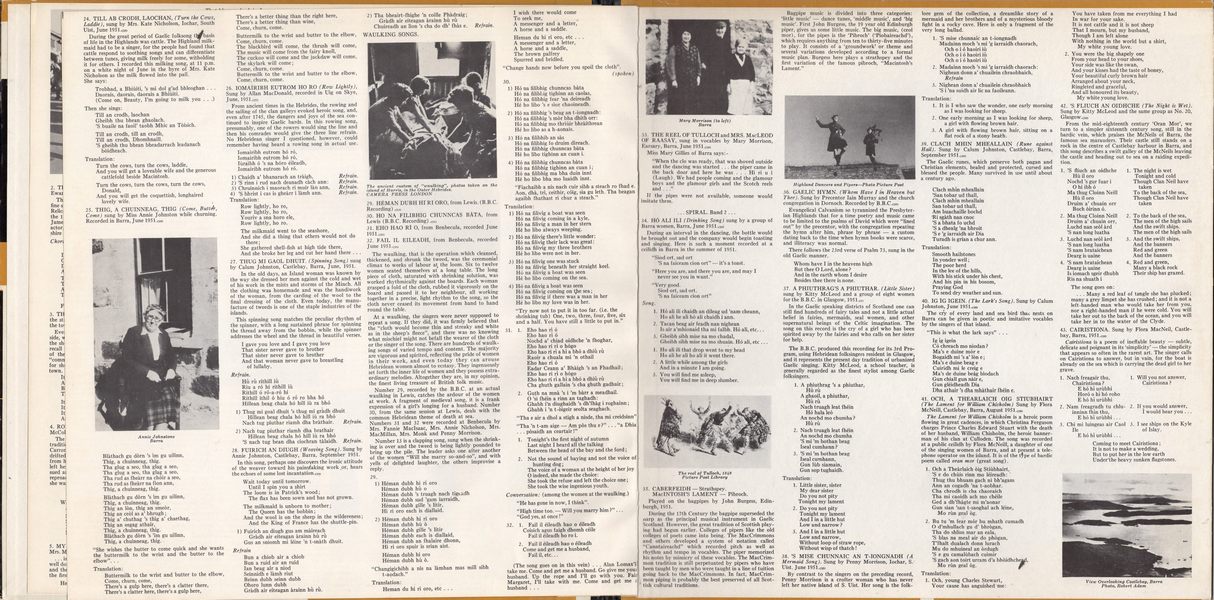

The waulking, that is the operation which cleansed, thickened, and shrunk the tweed, was the ceremonial climax to weeks of labour at the loom. Six to twelve women seated themselves at a long table. The long piece of cloth, saturated with shrinking solution, was worked rhythmically against the boards. Each woman grasped a fold of the cloth, rubbed it vigorously on the board and passed it to her neighbour, all working together in a precise, light rhythm to the song, so the cloth never ceased its movement from hand to hand round the table.

At a waulking, the singers were never supposed to repeat a song. If they did, it was firmly believed that the "cloth would become thin and streaky and white as in the sheep's fleece", and there was no knowing what mischief might not befall the wearer of the cloth or the singer of the song. There are hundreds of waulking songs of varied tempo and content. The majority are vigorous and spirited, reflecting the pride of women in their work, and even today they can arouse Hebridean women almost to ecstasy. They ingenuously set forth the inner life of women and they possess extraordinary melodies. Altogether they are, in my opinion, the finest living treasure of British folk music.

Number 29, recorded by the B.B.C. at an actual waulking in Lewis, catches the ardour of the women at work. A fragment of medieval song, it is a frank expression of a girl's longing for a husband. Number 30, from the same session at Lewis, deals with the common Hebridean theme of death at sea.

Numbers 31 and 32 were recorded at Benbecula by Mrs. Fannie MacIsaac, Mrs. Annie Nicholson, Mrs. MacMillan, Mrs. Monk and Penny Morrison.

Number 13 is a clapping song, sung when the shrinking is over and the tweed is being lightly pounded to bring up the pile. The leader asks one after another of the women "Will she marry so-and-so", and with yells of delighted laughter, the others improvise a reply.

33. The Reel Of Tulloch & Mrs. Macleod Of Raasay, sung in vocables by Mary Morrison, Earsary, Barra, June 195l.

Miss Mary Gillies of Barra says:— "When the clo was ready, that was shoved outside and the dancing was started … the piper came in the back door and here he was … Hi ri u i (Laugh). We had people coming and the glamour boys and the glamour girls and the Scotch reels and … "

If the pipes were not available, someone would imitate them.

34. Hó Ali Ili (Drinking Song) sung by a group of Barra women, Barra, June 1951.

During an interval in the dancing, the bottle would be brought out and the company would begin toasting and singing. Here is such a moment recorded at a ceilidh in Barra in the summer of 1951.

35. Caberfeidh (Strathspey) & MacIntosh's Lament (Pibroch), Played on the bagpipes by John Burgess, Edinburgh, 1951.

During the 17th Century the bagpipe superseded the harp as the principal musical instrument in Gaelic Scotland. However, the great tradition of Scottish playing had begun earlier. Colleges of pipers like the old colleges of poets came into being. The MacCrimmons and others developed a system of notation called "Canntaircachd" which recorded pitch as well as rhythm and tempo in vocables. The piper memorized his notes by mimicry of these vocables. The MacCrimmon tradition is still perpetuated by pipers who have been taught by men who were taught in a line of tuition going back to the MacCrimmons. In fact, MacCrimmon piping is probably the best preserved of all Scottish cultural traditions.

Bagpipe music is divided into three categories: 'little music' — dance tunes, 'middle music', and 'big music'. First John Burgess, the 19 year old Edinburgh piper, gives us some little music. The big music, (ceol mor), for the pipes is the 'Pibroch' ('Piobaireachd'), which requires anything from ten to thirty-five minutes to play. It consists of a 'groundwork' or theme and several variations developed according to a formal music plan. Burgess here plays a strathspey and the first variation of the famous pibroch, "Macintosh's Lament."

36. Gaelic Hymn, (Whom Have I in Heaven but Thee). Sung by Precentor Iain Murray and the church congregation in Dornoch. Recorded by B.B.C.

Evangelical Calvanism so tyrannized the Presbyterian Highlands that for a time poetry and music came to be limited to the psalms of David which were "lined out" by the precentor, with the congregation repeating the hymn after him, phrase by phrase — a custom dating back to the time when hymn books were scarce, and illiteracy was normal.

37. A Phiuthrag's A Phiuthar, (Little Sister) sung by Kitty McLeod and a group of eight women for the B.B.C. in Glasgow, 1951.

In the Gaelic speaking districts of Scotland one can still find hundreds of fairy tales and not a little actual belief in fairies, mermaids, seal women, and other supernatural beings of the Celtic imagination. The song on this record is the cry of a girl who has been spirited away by the fairies and who calls on her sister for help.

The B.B.C. produced this recording for its 3rd Program, using Hebridean folksingers resident in Glasgow, and it represents the present day tradition of urbanized Gaelic singing. Kitty McLeod, a school teacher, is generally regarded as the finest stylist among Gaelic folksingers.

38. 'S Mise Chunnaic An T-Iongnadh (A Mermaid Song). Sung by Penny Morrison, Iochar, S. Uist. June 1951.

By contrast to the singers on the preceding record, Penny Morrison is a crofter woman who has never left her native island of S. Uist. Her song is the folklore gem of the collection, a dreamlike story of a mermaid and her brothers and of a mysterious bloody fight in a rocky cave. Here is only a fragment of the very long ballad.

39. Clach Mhin Mheallain (Rune against Hail). Sung by Calum Johnston, Castlebay, Barra, September 1951.

The Gaelic runes, which preserve both pagan and Christian elements, healed and protected, cursed and blessed the people. Many survived in use until about a century ago.

40. Ig Ig Igein (The Lark's Song). Sung by Calum Johnston, June 1951.

41. Och, A Theárlaich Óig Stiúbhairt (The Lament for William Chisholm) Sung by Flora McNeill, Castlebay, Barra, August 1951.

The Lament for William Chisholm is a heroic poem flowing in great cadences, in which Christina Ferguson charges Prince Charles Edward Stuart with the death of her husband, William Chisholm, the heroic banner-man of his clan at Culloden. The song was recorded at a public ceilidh by Flora McNeill, a daughter of one of the singing women of Barra, and at present a telephone operator on the island. It is of the type of bardic poem called oran mor (great song).

42. 'S Fliuch An Oidhche (The Night is Wet). Sung by Kitty McLeod and the same group as No. 20, Glasgow.

From the mid-eighteenth century 'Oran Mor', we turn to a simpler sixteenth century song, still in the bardic vein, which praises the McNeils of Barra, the famous sea marauders. Their castle still stands on a rock in the centre of Castlebay harbour in Barra, and this song describes a swift galley of the McNeils leaving the castle and heading out to sea on a raiding expedition.

43. Cairistiona. Sung by Flora MacNeil, Castlebay, Barra, 1951.

Cairistiona is a poem of ineffable beauty — subtle, delicate and poignant in its 'simplicity' — the simplicity that appears so often in the rarest art. The singer calls on Cairistiona to answer, but in vain, for the boat is already on the sea which is carrying the dead girl to her grave.

THE LOWLANDS