|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

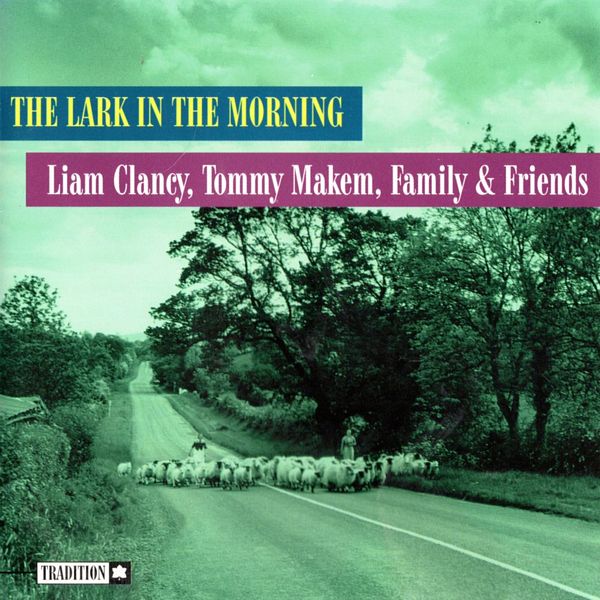

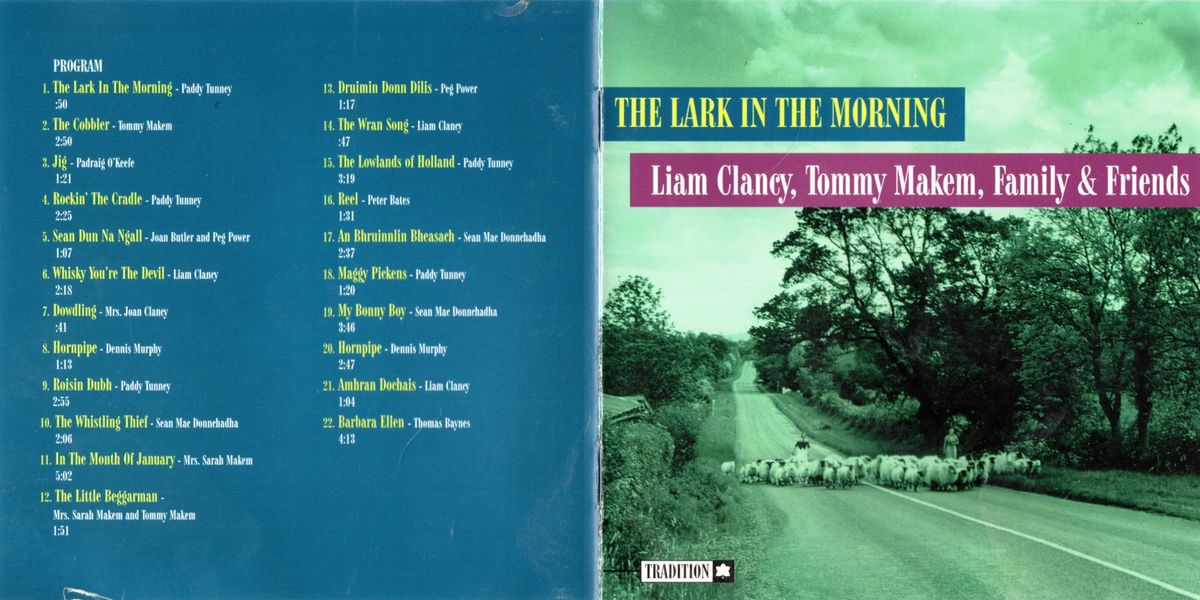

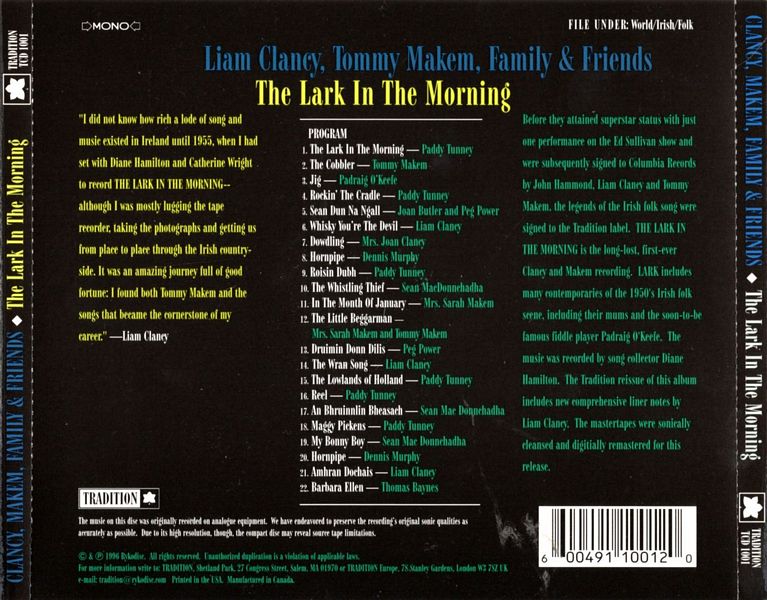

Before they attained superstar status with just one performance on the Ed Sullivan show and were subsequently signed to Columbia Records by John Hammond, Liam Clancy and Tommy Makem, the legends of the Irish folk song were signed to the Tradition label. THE LARK IN THE MORNING is the long-lost, first-ever Clancy and Makem recording. LARK includes many contemporaries of the 1950's Irish folk scene, including their mums and the soon-to-be famous fiddle player Padraig O'Keefe. The music was recorded by song collector Diane Hamilton. The Tradition reissue of this album includes new comprehensive liner notes by Liam Clancy. The master tapes were sonically cleansed and digitally re-mastered for this release.

THE LARK IN THE MORNING

"THE LARK IN THE MORNING SHE RISES OFF HER NEST

SHE GOES HOME IN THE EVENING WITH THE DEW ALL ON HER BREAST

AND LIKE THE JOLLY PLOUGH BOY SHE WHISTLES AND SHE SINGS

SHE GOES HOME IN THE EVENING WITH THE DEW ALL ON HER WING"

"I did not know how rich a lode of song and music existed in Ireland until 1935, when I had set with Diane Hamilton and Catherine Wright to record THE LARK IN THE MORNING — although I was mostly lugging the tape recorder, taking the photographs and getting us from place to place through the Irish countryside. It was an amazing journey full of good fortune: I found both Tommy Makem and the songs that became the cornerstone of my career."

The songs and tunes on this album are from a much more innocent time and they are presented here in all their unadorned simplicity. They were recorded by the American folk music collector. Diane Hamilton, between August and December 1955. Being an accomplished singer and musician herself (she played the harp and the mountain dulcimer), she had a great love of folk music and set out to follow in the foot-steps of Alan Lomax and Jean Ritchie, who had recorded extensively in Ireland a few years before. I was privileged to be part of the making of this album, although my role was mainly confined to lugging about the equipment and taking photographs. One dark Saturday night in early October, 1955, I answered a knock at our door on William Street, Carrick-on-Suir. a small town in south Tipperary in Ireland. It was Diane and her traveling companion, the copious Catherine Wright. Diane said they were directed to us by my brothers Paddy and Tom. who were running a theatre in New York's Greenwich Village at the time. "They tell me your mother, 'Mammy Clancy' they called her, has a great store of children's songs."

Well, there followed the kind of night that was to become all too familiar during the next couple of months as we set out on our Odyssey to find the singers and musicians Diane was seeking; a night overflowing with tea and music, cakes and biscuits, chat and song and of tape wound down in the small hours. Diane asked my brother Bobby and me if we would like to join them next morning on their trip to Kerry to track down the renowned fiddle player, Padraig O'Keefe. "I usually go to half eleven Mass." I told her. "But if I'm up for the ten o'clock, I'll go along." I did get up, and that decision literally changed the course of my life.

At eleven o'clock the next morning we set out for Kerry on the trail of Padraig O'Keefe. Bobby and I sat in the back of the rented Austin A 40. Diane drove and the weighty Catherine made a fair dent in the front passenger seat. There's an expression in Ireland, "shorten the road," meaning that a song and a story will make the road feel short. Catherine shortened the road to Kerry for us with her sardonic New York wit and commentary. She didn't exactly say that her trip to Ireland was a disaster, but the litany of complaints implied that the Ireland of the fifties left much to be desired by way of creature comforts. We laughed and sang all the way to Kerry with Diane's incessant questioning sometimes driving us to distraction. "Have you got a version of this one? It's a play-party song from Kentucky." I didn't know what the hell a play-party song was. Or, "Is there a local version of Barbara Allen?" Soon the mountains of Kerry, a sight I'd never seen before, loomed near.

Finding Padraig O'Keefe was not the easy task one might think. We were told he was a school master and could be found al his school near Scartaglen. When we did find the school, it was boarded up. A neighbour wasn't much help. All she could say was "Ah sur, poor Padraig, poor Padraig (sigh)." "Oh dear, he's not dead is he?," Diane asked. "No, no. Worse!" she said, "He took to the fiddle." Taking to the fiddle or taking to the drink were considered a fate worse than death, and Padraig had taken to both.

We finally found him in a pub in Castleisland. He was not well. He certainly was not fit to cope with the overbearing "Yanks." However, he was clever enough to realize that there could be a "cure" in this and maybe more. Stories abound about Padraig and the drink. He once got a weakness and collapsed in his local pub in Scartaglen. In spite of the fact that he was heavily in debt to "the slate," he was given a large whiskey to revive him. A second one was even put up in front of him when he was strong enough to sit up on a bar stool. Contemplating the amber magic in the glass in front of him he noticed that a comrade-in-drink was eyeing his whiskey with a greedy glint, Padraig rounded on him. "Would you ever go off," he said, "and have your own weakness!"

There was a small problem when it came to recording him. No fiddle. It was in "hock" behind the bar at his local in Scart. If we wanted to record him. we'll have to secure its freedom by paying off the ransom. Many adventures later, we finally set up the recording equipment in the pub. He was not at his best, but a couple of whiskies later he looked up slyly and said, "She's purring now." A couple more and he announced, "High purring." "The fiddle was always referred to a "she." "The best wife a man ever had," he used to announce. "All you have to do is stroke her belly and she's purring for you." For me though, the treasure that emerged from the session was the photograph of Padraig with the glass of Guinness in one hand and the fiddle and bow in the other. Look carefully at the bow. The strings are held away from the wood by the cork of a porter bottle. Many serious musicians pay thousands of dollars for the right how to suit them. Vanity!

I saw sights and heard music on that recording trip that I never knew existed on this island. It was to set the cornerstone, for me, of a life of involvement and fascination with the world of traditional music and song.

We traveled through Kerry and Limerick and Clare, up through Galway. Mayo and Sligo. In Siglo, I got to visit the grave of W.B. Yeats, another major influence in my life (and countless other lovers of poetry). I got to climb Ben Bulben, the mountain in whose shadow Yeats is buried and Knocknarea, where Queen Maeve lies under her cairn of stones.

THE WIND HAS BUNDLED UP THE CLOUDS HIGH OVER KNOCKNAREA

AND THROWN THE THUNDER ON THE STONES FOR ALL THAT MAEVE CAN SAY.

Catherine, of course, never joined us in any of the forays that involved physical exertion and sweat. One day she unceremoniously presented Bobby and me with a jar of Mum deodorant. "I'm not traveling another mile in this car with you two until you rub some of this under your 'oxters.' as you put it so quaintly in this country, Gawd. you smell like mountain sheep!"

Speaking of armpits, there was a hotel in Armagh where we encamped during the recording sessions at the Makem house in Keady. Primitive and dangerous, with narrow winding timber stairs, I encountered Catherine one morning on a particularly narrow bend when two normal sized people would find it difficult to pass. She was dressed outlandishly in a floorlength dressing gown of multicoloured stripes, yards and yards of it. and carried in her hand a chamber pot covered with newspaper. Completely unabashed, she commanded me to "Make way young man!" "Catherine, where are you off to?" I asked. "Well, I'm not going cycling." she retorted, as she crushed by me with her aromatic cargo.

The recording sessions at the Makems' house were memorable. Peter, with his pipe and fiddle — "Oh aye. Oh begob aye." was all he ever seemed to say — and Jack, "Don't give that man another drop or he won't he able to play at all." Ann Jane Kelly. the neighbour, with a perpetual fag. bigger than herself, shouting, "Make the tay, make the tay." Tommy in the corner, nearly as shy as myself (hard to imagine now), and the girls hustling and bustling, making pots of tea and cutting cake with nonstop (and to me, a southerner, completely unintelligible) chatter and they all buzzing around the Queen Bee herself, Sarah Makem, as she sat, placid in the eye of the hurricane.

It was so much like the Clancy household it was uncanny, in our case Mammy Clancy being the Queen Bee. All that was different were the accents.

Sarah Makem had a vast store of songs which the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem would later plunder. Seán O'Boyle. too, the great musical scholar and folklorist, was a regular at the sessions. From him I got the beautiful Gaelic sung "Buachaill on Erine" which was "Englishized" by a Scottish journalist and became the Irish "folk song" "Come By The Hills." A mighty day and night too were spent with the great Paddy Tunney in Letlerkenny, County Donegal. What a trip that was, with half the town of Keady in the entourage, singing all the way. After a session of blinding poetry and song with Paddy, and his mother, that went on into the early hours, there was an air of growing unease among the Keady contingent at the thought of driving back along the dark winter roads of the North at such an hour. The "B specials" were active and dangerous at the time. They had shot and killed a young man near Keady the previous year. The "B specials" were the Protestant militia, armed civilians really, who patrolled the roads of Northern Ireland, in the fifties. The province, at that time, was very much like South Africa under apartheid, the Catholics being the blacks. However, we need not have worried. Coming out of the hotel in Letterkenny, someone had stepped in "doggy doo" (as Catherine so delicately put it) and although we were slopped several times by the "II specials," they quickly backed off when they got the whiff emanating from the lead car.

Tommy and I struck up a great friendship at this time. Our interests were strikingly similar; girls, theatre and singing, in that order. We went to a dance one night in Armagh. The band knew Tommy and invited him up on (he stage to sing a song. The hall was mobbed with young people and I thought "My God, this crowd will never listen." He got on stage and asked for a chair. Putting his right foot up on his left knee, he started making the motions of mending his shoe. He began — "Oh me name is Dick Darby, I'm a cobbler." Those in front started shushing those behind and before he'd finished the first verse there was total silence. I was impressed.

That night was the beginning of an association that was to last decades and produce scores of albums both as the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem and, later, as Makem and Clancy. Together, we did plays in New York for poverty-line pay, plowed a furrow for a new attack on Irish folk song, won an Emmy for our Canadian TV series, and performed throughout the English speaking world for presidents and peasants. Before we parted ways professionally, in 1987, we had made something in the region of fifty albums of music, poetry and song. As with most things that grow and flourish organically, our careers started out quietly and without fanfare — much like the songs and tunes on this album, THE LARK IN THE MORNING.

— Liam Clancy