|

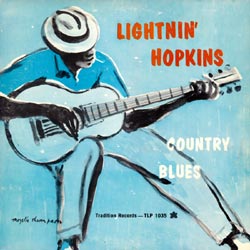

Sleeve Notes

Houston's Third Ward is a tiny kingdom. Sam 'Lightnin' Hopkins, is its prophet and jester.

Most of his 47 years he's wandered a few blocks of Dowling Street, a cocky, loping figure with a guitar slung across his back pausing now and then to gather a crowd and coax their coins into his hat.

He is — in the finest sense of the word — a minstrel: a street singing, improvising song maker born to the vast tradition of the blues. His only understanding of music is that it be as personal as a hushed conversation.

His lanky frame bent to the guitar, he virtually dances his songs, posing with self-delight, at times contorting as if a man in the grip of a strong purgative. For long introverted moments pain shades his puckered face, then suddenly he bursts into a blazing gold-tooothed grin. A rich moan settles on the haze of exhaust fumes. A phrase hangs suspensefully as he twirls the guitar, bringing it back to position precisely with the beat. Over the dark sunglasses slipping down his nose, he winks at a friend and makes up a line for him. He drifts from a prison work song to a mistreated blues and then slips into a boogie-paced line of patter in which he gaily mocks the bystanders. Lifting a limp hand in a sardonic command he picks out a girl in the crowd and tells her, "Okay — now twist it.!" And she does.

The songs speak about the railroads and jails, the fickle love and hard times, gaining immediacy as the lines are newly melded at each performance. Unpredictably wandering thru a song, Lightnin bends the traditional blues to his purpose, adds his own spontaneous rime, involves his listeners with impromptu narrative and asides tossed out with a knowing grimmace. Jeweled guitar phrases heighten the mood as he formulates the verse to follow.

The language of these blues is deceptively simple, casual in its honesty, yet firmly in touch with the realities and primary emotions. In the hands of the singer, the guitar is not accompaniment but corollary: the joy or pain of the song's origin, the passion re-experienced. Caught in the flow the metrical pattern strains or telescopes to fit the singer's need. Autobiographical fact and legendary wisdom merge in one complete expression. For Lightnin it is a total expression. His personality is the half-spoken blues line ending in a moan or an impish chuckle.

Lord, turn your twister the other way …

These fifteen selections are a sampling of Lightnin's moods. He talks to the sun in a work song of the Texas river bottoms (Go Down Old Hannah) and stages a capsule drama (Gonna Pull A Party). He sees himself as a cuckold (Hear My Black Dog Bark), reminisces of his family (Bunion Stew), and dwells on a momentary state of mind (Rainy Day Blues). His songs must always absorb the immediate circumstances and so the recording process itself becomes the subject of veiled comment in You Got To Work To Get Your Pay.

The blues abound with the tragic sense of life and Lightnin makes it his personal property. According to musicologist John W. Work, "The blues singer translates every happening into his own intimate inconvenience." According to Lightnin Hopkins, "Can't see why all this evil coming down on me." This egocen-tricity is his weakness or greatness depending on the breadth of spirit with which he casts his troubles. Subject to the pitfalls of an unreflective art, he may drift into banal repetition in one moment, and in the next strike out with some deep intimacy, stunning with humor or melancholy insight.

He necessarily deals in the orphic manners close to his tradition; yet, Lightnin is that rare article, the genuine folk artist whose appeal carries his native expression beyond its own culture. Universal experience is vividly stated in his extraordinary staging of dramatic scenes in the first person, present tense. In Prison Blues Come Down On Me he conjures images of the vagrant farm boy trudging dustily home from the prison farm, the apprehensive questions and wry comments set against the guitar's unrelenting bitterness. Here, he unknowingly echoes the opening scenes of "The Grapes of Wrath": Tom Joad's encounter with Muley. Lightnin never heard of the John Steinbeck novel; his experience of the chain gang is first hand and the images entirely personal.

That red-eyed sergeant, boy, coming after me …

Prison Blues too is an example of Lightnin's incredible spontaneity. During the recording session he was asked for a "sad" piece. After a moment's thought he called Luke 'Long Gone' Miles into the room. (Part of the blues tradition is the youthful errand boy and apprentice who accompanies the master.) The rehearsal' consisted in its entirey of Lightnin's telling him. "Now you be some old boy standing in the road and I'll be some old boy gitting back from the prison farm …"

In Lightnin, a major folk tradition survives. The East Texas 'Piney Woods' — at the center of a triangle lying between Dallas: Houston, and Shreveport — is a magic spring from which the great blues minstrels have flowed in an unbroken line. The tradition of this scraggy land — typified by the long guitar runs and the mixed narrative and song — is the best known of the American blues owing to the early and vastly influential records of Blind Lemon Jefferson and Texas Alexander.

Lightnin is from Leon County at the center of the 'Piney Woods.' As a brash youngster he tagged after Blind Lemon at the Baptist 'association' meetings. Later, he accompanied Texas Alexander as the aging singer — penniless and forgotten after a prison term cut short his recording career — begged along Houston's West Dallas Street.

"But nobody taught me," Lightnin says. "I just see how they do and then I do it my own way. Make my own songs." His roots are not the motley impressions of phonograph records but the distinct heritage of his birthplace.

He is a strangely innocent man, isolated and oblivious to much of contemporary life, and ignorant in some astounding ways. (Until the time of this recording he had never heard of long playing records even tho an LP reissue of his early recordings was on sale within a block of his home.) Yet, if limited, his experience within his own culture is deep and he is a man casually versed in human wisdom. Like many of those who make up his audiences, beneath the sharp urban manners he is pure 'country.' He belongs to the East Texas cotton lands in an almost tribal sense.

If a mule starts to run away with the world …

Bound to the city and detesting the Yessuh behavior demanded of a southern Negro, he chooses to seclude himself within his own segregated society with its self-sufficient mores. His songs often depict this oddly isolated world — a Negro ward wedged in but not quite part of the city — revealing his easy familiarity with the enforced poverty, the quick violence, policy slip gambling, mojo charms, and empty gin bottles. Within his world, Lightin is adulated and free to indulge in such swaggering habits as planting a kiss on the cheek of any young lady that happens by.

"I been married nine times," he says, explaining the source of many songs. "But only once with holding hands and all in front of a preacher. Them others, they just be around … Don't you know I'm some bad man?

"My real wife — her name was Elmer just like a man — lives up at Crockett, Texas where I had that trouble that time. Had to cut an old boy and they give me time on the County farm. It wasn't the penitentiary but it was like second to the bottom." (The Texas penal farms dotting the Trinity and Brazos river bottoms are commonly known as 'the bottom'.) "It was old Judge McClain — he's dead and gone I suppose — give me that time. Then he come and made 'em turn me loose, saying 'That boy didn't do nothing so much …' You drive up around Crockett on them roads? Well, I built on them roads myself with a chain locked around this ankle. See, it's a scar there, festering and scabby ain't it? Back in '37 or so. That Judge came and says to turn me loose after I'd sung him a song about 'How bad and how sad to be a fool.'

"Old Texas Alexander was my cousin and we'd work together. He couldn't play nothing but he could sing. We start off plenty of places together. He died about four years ago. Blind Lemon!" He'd be around Buffalo and Leona when all them preachers come together and little kid I was, I'd just start in playing with him. If you played good, he'd have a little smile. I heard about him being frozen and found dead in Chicago that time. Then there was Blind Butler sang all them religious songs. He's dead I suppose.

"Most the time I be around Houston, just wandering. From up there on Dowling I'd ride the bus to West Dallas Street and have $7, $8 by the time the bus brought me back. They'd nobody get off the bus, just keep ndin' while I'm playing. One night it's two police cars stop me and ask me where I got all my money. Say, 'Where you been stealing?' I just show them this guitar and tell 'em, 'This makes my living'."

Lightnin was first recorded in 1946 by a firm devoted to the jukebox trade. Since then, increasingly pursued by amplifiers, echo chambers, and thudding drums, he has appeared on a dozen labels. His near pathetic attempts to conform to the gimmick-oriented demands of these firms — typified by the one that dubbed in the sound of a sobbing voice over one of his blues — have resulted in nearly 200 selections of a nondescript Lightnin in competition with the rock n' roll industry. The subleties of his voice have been shouted away, the dramatics of his guitar forced to become acrobatics flung against deadly up-tempos. He enjoyed several hits but was soon lost in the shuffle of fads. But here and there, the strength of his personality showed through the haze of gimmicks and these records began to excite attention among followers of the country blues. His early sides for the defunct Houston firm, Gold Star, became collector's items. Discographers traced his career and musicologists termed him a "primitive … belonging to the sources." The realization came that Lightnin is not only the embodiment of a fundamental American tradition, but a creator who remakes the idiom in his own image: too caught by his own fury to be anything but unique.

Being an utterly personal and immediate offering, Lightnin's music does not readily lend itself to the blank-walled studio. For these recordings, engineering finesse was happily sacrificed in order that no inhibiting technical process dampen his rough edged moods. He was recorded in familiar circumstances, informally intent on playing for a friend. The microphone was made an incidental part of the scene and it heard him candidly, catching his spontaneity at its fullest.

After several mock sessions to ease the sense of pressure instilled by his previous recording experience, he warmed to the procedure, performing as freely and with all the characteristic surprises of his streetcorner manner. If not virtually heard, the winks and grins, the face drawn in pain and his dancing forward on his chair, the winning maze of gestures and tossing his body to mark an accent — these too are caught by the recording.

This is the man in his own terms: "Lightnin Hopkins, himself, alone."

— MACK McCORMICK