|

|

Sleeve Notes

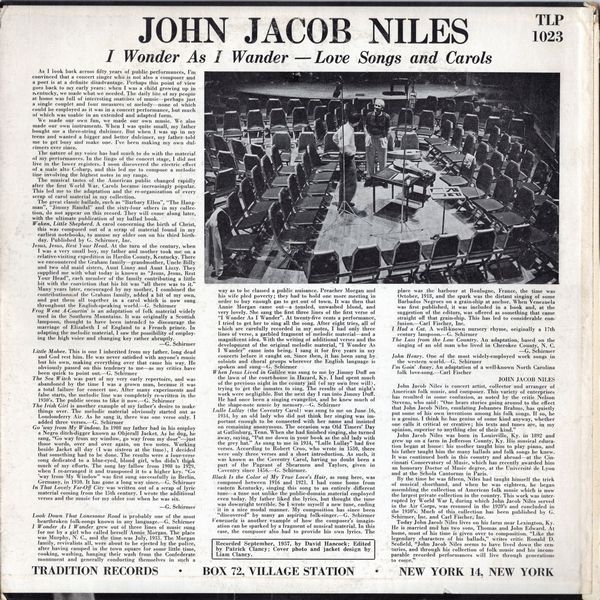

As I look back across fifty years of public performances, I'm convinced that a concert singer who is not also a composer and a poet is at a definite disadvantage. Perhaps this point of view goes back to my early years: when I was a child growing up in Kentucky, we made what we needed. The daily lite of my people at home was full of interesting snatches of music — perhaps just a single couplet and four measures of melody — none of which could be employed as it was in a concert performance, but much of which was usable in an extended and adapted form.

We made our own fun, we made our own music. We also made our own instruments. When I was quite small, my father bought me a three-string dulcimer. But when I was up in my teens and wanted a bigger and better dulcimer, my father told me to get busy and make one. I've been making my own dulcimers ever since.

The nature of my voice has had much to do with the material of my performances. In the lingo of the concert stage, I did not live in the lower registers. I soon discovered the electric effect of a male alto C-sharp, and this led me to compose a melodic line involving the highest notes in my range.

The musical tastes of the American public changed rapidly after the first World War. Carols became increasingly popular. This led me to the adaptation and the re-organization of every scrap of carol material in my collection.

The great classic ballads, such as "Barbary Ellen", "The Hangman", "Jimmy Randal" and the sixty-four others in my collection, do not appear on this record. They will come along later, with the ultimate publication of my ballad book.

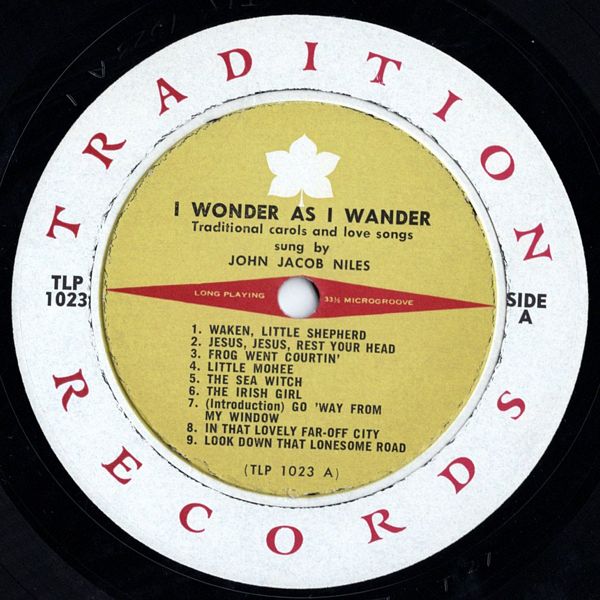

Waken, Little Shepherd. A carol concerning the birth of Christ, this was composed out of a scrap of material found in my earliest notebooks, to amuse my older son on his third birthday. Published by G. Schirmer, Inc.

Jesus, Jesus, Rest Your Head. At the turn of the century, when I was a very small boy, my father and mother took me on a relative-visiting expedition in Hardin County, Kentucky. There we encountered the Graham family — grandmother, Uncle Billy and two old maid sisters, Aunt Linny and Aunt Lizzy. They supplied me with what today is known as "Jesus, Jesus, Rest Your Head", each member of the family contributing a little bit with the conviction that his bit was "all there was to it." Many years later, encouraged by my mother, I combined the contributions; of the Graham family, added a bit of my own, and put them all together in a carol which is now sung throughout the English-speaking world. — G. Schirmer

Frog Went A-Courtin' is an adaptation of folk material widely used in the Southern Mountains. It was originally a Scottish lampoon, thought to have been intended to discourage the marriage of Elizabeth I of England to a French prince. In adapting the melodic material, I saw the possibility of employing the high voice and changing key rather abruptly. — G. Schirmer

Little Mohee. This is one I inherited from my father, long dead and God rest him. He was never satisfied with anyone's music but his own, making everything over that came his way. He obviously passed on this tendency to me — as my critics have been quick to point out. — G. Schirmer

The Sea Witch was part of my very early repertoire, and was abandoned by the time I was a grown man, because it was a total failure for concert use. After many experiments and false starts, the melodic line was completely re-written in the 1930's. The public seems to like it now. — G. Schirmer

The Irish Girl is another example of my father's desire to make things over. The melodic material obviously started out as Londonderry Air. As he sang it, there was one verse only. I added three verses. — G. Schirmer

Go 'way from My Window. In 1908 my father had in his employ a Negro ditch-digger known as Objerall Jacket. As he dug, he sang, "Go way from my window, go way from my door" — just those words, over and over again, on two notes. Working beside Jacket all day (I was sixteen at the time), I decided that something had to be done. The results were a four-verse song dedicated to a blue-eyed, blond girl, who didn't think much of my efforts. The song lay fallow from 1908 to 1929, when I re-arranged it and transposed it to a higher key. "Go 'way from My Window" was first sung successfully in Berlin, Germany, in 1930. It has gone a long way since. — G. Schirmer

In That Lovely Far-Off City was written out of a scrap of lyric material coming from the 15th century. I wrote the additional verses and the music for my older son when he was six. — G. Schirmer

Look Down That Lonesome Road is probably one of the most heartbroken folk-songs known in any language. — G. Schirmer

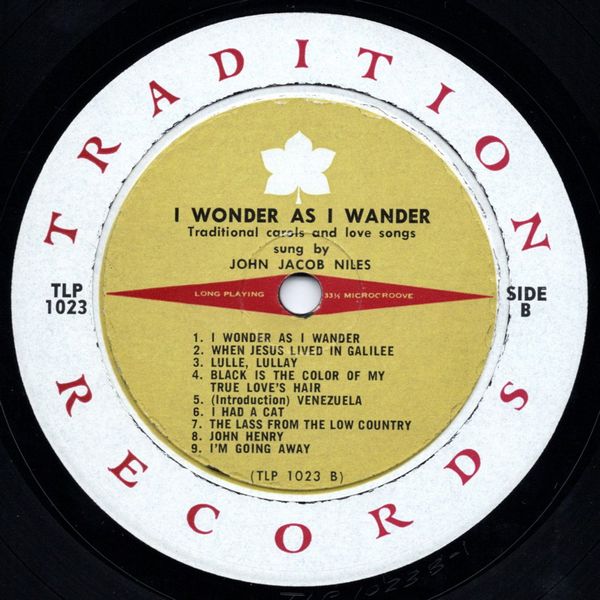

I Wonder As I Wander grew out of three lines of music sung for me by a girl who called herself Annie Morgan. The place was Murphy, N. C., and the time was July, 1933. The Morgan family, revivalists all, were about to be ejected by the police, after having camped in the town square for some little time, cooking, washing, hanging their wash from the Confederate monument and generally conducting themselves in such a way as to be classed a public nuisance. Preacher Morgan and his wife pled poverty; they had to hold one more meeting in order to buy enough gas to get out of town. It was then that Annie Morgan came out — a tousled, unwashed blond, and very lovely. She sang the first three lines of the first verse of "I Wonder As I Wander". At twenty-five cents a performance. I tried to get her to sing all the song. After eight tries, all of which are carefully recorded in my notes, I had only three lines of verse, a garbled fragment of melodic material — and a magnificent idea. With the writing of additional verses and the development of the original melodic material, "I Wonder As I Wander" came into being. I sang it for five years in my concerts before it caught on. Since then, it has been sung by soloists and choral groups wherever the English language is spoken and sung — G. Schirmer

When Jesus Lived in Galilee was sung to me by Jimmy Duff on the lawn of the court-house in Hazard, KY. I had spent much of the previous night in the county jail (of my own free will o. trying to get the inmates to sing. The results of that night's work were negligible. But the next day I ran into Jimmy Duff. He had once been a singing evangelist, and he knew much of the shape-note music by memory. — G. Schirmer

Lulle Lullay (the Coventry Carol) was sung to me on June 16, 1934, by an old lady who did not think her singing was important enough to he connected with her name and insisted on remaining anonymous. The occasion was Old Timers' Day at Gatlinburg, Tenn. When she had finished singing, she turned away, saying, "Put me down in your book as the old lady with the grey hat." As sung to me in 1934, "Lulle Lullay" had five verses. According to Robert Croo, who wrote in 1530, there were only three verses and a short introduction. As such, it was known as the Coventry Carol, having no doubt been a part of the Pageant of Shearmen and Taylors, given in Coventry since 1456. — G. Schirmer.

Black Is the Color of My True Love's Hair, as sung here, was composed between 1916 and 1921. I had come home from eastern Kentucky, singing this song to an entirely different tune — a tune not unlike the public-domain material employed even today. My father liked the lyrics, but thought the tune was downright terrible. So I wrote myself a new tune, ending it in a nice modal manner. My composition has since been "discovered" by many an aspiring folk-singer. — G. Schirmer

Venezuela is another example of how the composer's imagination can be sparked by a fragment of musical material. In this case, the composer also had to provide his own lyrics. The place was the harbour at Boulogne, France, the time was October, 1918, and the spark was the distant singing of some Barbados Negroes on a grain-ship at anchor. When Venezuela was first published, it was included in a book and, at the suggestion of the editors, was offered as something that came straight off that grain-ship. This has led to considerable confusion. — Carl Fischer, Inc.

I Had a Cat. A well-known nursery rhyme, originally a 17th century lampoon. — G. Schirmer

The Lass from the Low Country. An adaptation, based on the singing of an old man who lived in Cherokee County, N. C. — G. Schirmer

John Henry. One of the most widely-employed work songs in the western world. — G. Schirmer

I'm Gain' Away. An adaptation of a well-known North Carolina folk love-song. — Carl Fischer

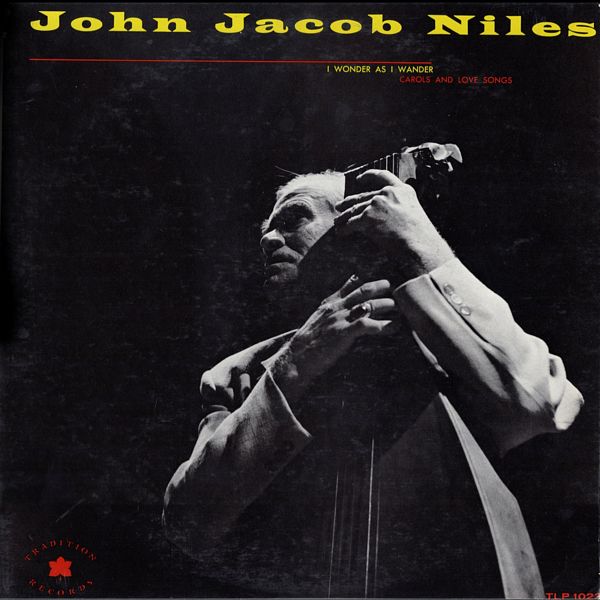

JOHN JACOB NILES

John Jacob Niles is concert artist, collector and arranger of American folk music, and composer. This variety of enterprises has resulted in some confusion, as noted by the critic Nelson Stevens, who said: "One hears stories going around to the effect that John Jacob Niles, emulating Johannes Brahms, has quietly put some of his own inventions among his folk songs. If so, he is a genius. I think he has genius of some kind anyway, whether one calls it critical or creative; his texts and tunes are, in my opinion, superior to anything else of their kind."

John Jacob Niles was born in Louisville, Ky. in 1892 and grew up on a farm in Jefferson County, Ky. His musical education began at home: his mother taught him to play piano, and his father taught him the many ballads and folk songs he knew. It was continued both in this country and abroad — at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music, which has recently awarded him an honorary Doctor of Music degree, at the Universite de Lyon and at the Schola Cantorum in Paris.

By the time he was fifteen, Niles had taught himself the trick of musical shorthand, and when he was eighteen, he began assembling the collection of American folk music which is now the largest private collection in the country. This work was interrupted by World War I, during which John Jacob Niles served in the Air Corps, was resumed in the 1920's and concluded in the 1930's. Much of this collection has been published by G. Schirmer, Inc. and Carl Fischer, Inc.

Today John Jacob Niles lives on his farm near Lexington, Ky. He is married and has two sons, Thomas and John Edward. At home, most of his time is given over to composition. "Like the legendary characters of his ballads," writes critic Ronald D. Scofield, "John Jacob Niles seems to have lived down the centuries, and through his collection of folk music and his incomparable recorded performances will live through generations to come."