|

|

Sleeve Notes

English folklorists, scholars, esthetes, musicologists and romanticists have long proclaimed that the traditional love songs of their country are among the most beautiful in the entire world. A rapid inspection of any printed collection of English folk songs will bear out the truth of their claim. From the earliest collections to the more recent findings of the folksong archives of the British Broadcasting Corporation, the English folk love song would in itself he sufficient reason to identify that country as one of the world's most important sources of traditional songlore, for love songs comprise such a large part of their traditional cultural heritage.

These songs are of diverse origin. Country lads and lasses, ploughboys and sailors, squires and tinkers, and broadside scriveners in every part of the country contributed to the shaping and reshaping of this rich tradition. Their circulation over long periods of time and vast distances have resulted in the creation of much exquisite folk poetry and music. The texts and tunes of many of these songs could hold their own in competition against the best songs turned out by known composers at the height of England's greatest poetic and musical glory.

We are indebted to the many English collectors who have painstakingly copied down songs collected from tradition, which in turn were published so that ever larger audiences might share their appreciation of this beautiful songlore. Most of these collectors, however, did not present us with a full report of this material. They took it upon themselves to act as moral censor in presenting these songs to us. Even as trustworthy a collector as Cecil Sharp believed it necessary to expurgate lines and stanzas from some of the finest of the songs he collected. And many of these songs were deemed in such bad taste that they never saw the inside of the printer's shop. Such songs are found only in the original manuscript collections residing in the British Museum and other institutions for the preservation of knowledge — and on the tongues and in the minds of folk-singers throughout England today. American audiences would find it impossible to hear these songs in their unexpurgated and "uncleansed" original form were it not for the researching and performance of these songs by folklorists like A. L. Lloyd, who find in the hold lustiness and unabashed frankness of these songs a true picture of a people little affected by the social inhibitions imposed by politico-clerically regimented societies.

Here, then, is a small, hut representative, sampling of TRADITIONAL ENGLISH LOVE SONGS as they were known and sung by centuries of plain English folk.

— K.S.G.

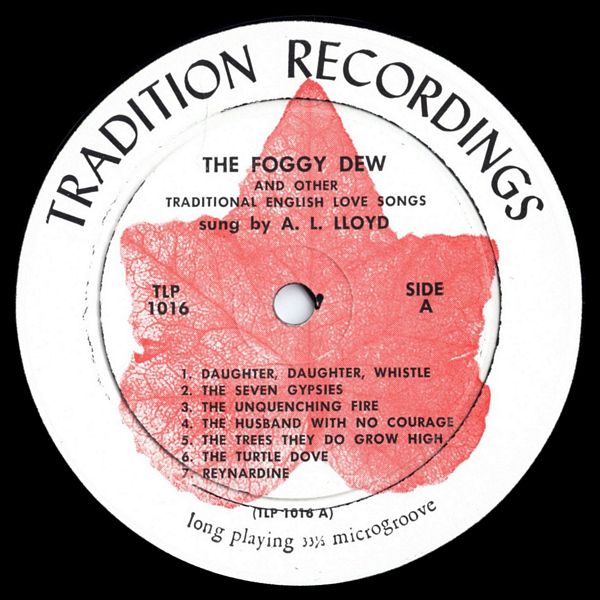

DAUGHTER, DAUGHTER, WHISTLE — This song, of the impatient girl who suddenly finds she can whistle when invited to whistle for a man, is known in many traditions, including Yiddish and Latin American. It has been suggested that the song means more than meets the ear, and that whistling is part of the witch's technique to summon the powers of darkness when she wants to realize a desire (akin to this belief is the sailor's horror of whistling for fear of raising a storm.) Somehow, though, the girl in the song sounds too healthy for a witch.

THE SEVEN GYPSIES — As the story goes, 300 years ago, Lady Jean Hamilton, married to the grim puritanical Earl of Cassilis, fell in love with John Faa, leader of a Scottish gypsy hand. The couple eloped, the band was pursued, and John Faa was captured and hanged. History is silent about this incident, hut the ballad (Child #200) has survived in many forms all over England, Scotland and America. Perhaps it was the piquancy of the situation in which the rich man's wife finds a poor man more desirable, that has commended it so long to the singers' fancy.

THE MAID'S LAMENT — Superior people incline to think folk songs are quaint harmless ditties, fragrant or comic, the amiable stammer of unlettered farmhands and servant girls. Popular folk song collections reflect this view. What then is to he made of such a song as this country girl's lament, that suddenly jets like a fountain of agony, and in two brief stanzas cries such passion and heartbreak as would bring down the stars.

THE HUSBAND WITH NO COURAGE IN HIM — Here is one of the hidden love songs of Britain, a song collected several times yet never considered fit to print. In it, a wife laments the sexual shortcomings of her husband. This kind of candor is not uncommon in Genro and Oriental song. On printed evidence it seems rare in West European musical folklore. Would manuscript collections show something different? The song is in unusual meter, considered by some to be Scottish, though in fact the song has been collected most often in the far south of England, in Somerset and Dorset.

THE TREES THEY DO GROW HIGH — This curious ballad is common all over the British Isles. In Scotland, the young bridegroom is named Charlie Cochrane, or Young Craigston. In the English versions, he remains anonymous. Child betrothal and early marriage were common enough in the Middle Ages and later, especially among noble families marrying for convenience. Most singers sense there is something hidden, something untold, behind the fate of the pathetic little hoy, so early a husband, a father, and a corpse.

THE TURTLE DOVE — Around 1770, leaflets hearing the words of this song were being hawked about the fairgrounds of England and Scotland. Milkmaids and horse-handlers would paste such leaflets on the walls of dairy and stable to learn the songs as they worked. Now and then, the place would get a new coat of whitewash and a fresh layer of song-sheets. Robert Burns obtained one of the Turtle Dove leaflets (it still exists, with his name scrawled on it in a boyish hand). Years later, he re-made the song into his famous lyric, My Love Is Like a Red Rose. Beautiful as Burns' song is, it is no better than the present version, evolved by country singers in Dorset.

REYNARDINE — A girl meets a man on the mountain and surrenders immediately to his persuasion. Who was Reynardine, with his irresistible charm, his glittering eye, his foxy smile? An ordinary man, or an outlaw maybe, or some supernatural lover? Is he that dreadful Mr. Fox in the English folk-tale, the elegant gentleman whose bedroom was full of skeletons and buckets of blood? The song does not say. It puts a finger to its lip and preserves the mystery, letting the enigmatic text and dramatic tune hint at unspeakable things.

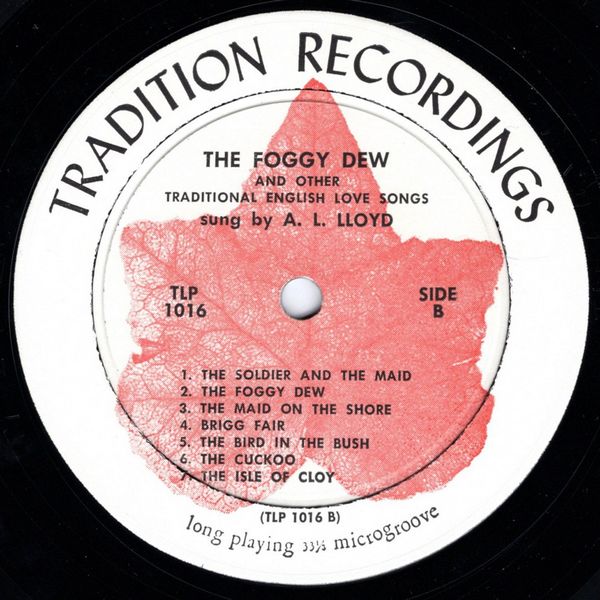

THE SOLDIER AND THE MAID — The encounter of the licentious soldier with the obliging young girl was an old story when Roman troops patrolled the great wall between England and Scotland. For newer versions, listen to the gossip around any army camp, any day, anywhere. Of the many ballads in the family of the Trooper and the Maid, this is perhaps the best. The song glides along the razor-edge between merriment and cruelty, and maybe that has commended it to the imagination of many singers. This is another of those ballads which words are usually "cleansed" in print.

THE FOGGY DEW — This is a true-life story known in many forms. Sometimes the girl is frightened by a ghost: the bugaboo; sometimes she is disturbed by the weather: the foggy dew. In either event, she comes to the old bachelor for comfort, and gets what she came for. The Irish have it as a sentimental piece of blarney. The Scots have it as a bawdy guffaw. The East Anglian ploughman has it the straightest . . . he sings it without a laugh or a tear, just as it happened. But the vital information he keeps to himself. The Foggy Dew is a song known all over England yet rarely is it seen in print except with the words bowdlerized. This is surely the age of the censors.

THE MAID ON THE SHORE — As the song comes to us, it is the bouncing ballad of a girl too smart for a lecherous sea-captain. But a scrap of the ballad as sung in Ireland hints at something sinister behind the gay recital. For there, the girl is a mermaid or siren. So the song the girl sang may once have been the song Homer spoke of, with which the strange bird-women beguiled unwary-seamen, and the sailors' deep sleep may have been, in earlier sets of the ballad, the sleep of death.

BRIGG FAIR — This is surely one of the most beautiful melodies in the English tradition. It is a rare song, reported from only one singer, Joseph Taylor, a onetime carpenter of Saxby, Lincolnshire. The song came to light by accident. A folk song competition was held at Brigg, Lincolnshire. The contest yielded no great finds. After it was over, an unsuccessful entrant, Mr. Taylor, came privately to the judges' tent, and, rather diffidently, he dredged up from memory this unforgettable song. Nowadays it is best known as the theme of Delius' orchestral rhapsody of the same name.

THE BIRD IN THE BUSH — Men may keep alive love songs that women would allow to die. Usually the women's song is of the ecstasy or grief of love. The man's song, in England anyway, rarely sings of the heights and depths of love. Rather it looks the facts in the eye, and reports fairly objectively of the situation. Sometimes a spade is called a spade; sometimes it's called a bird in the hush. Also known as Three Maidens A-Milking Did Go, the song has often been printed, but always bowdlerized to make a piece of bumpkin quaintness out of what is one of the most sensuous of all English songs. Here, for a change, is how the song is sung by the folk who made it.

THE CUCKOO — Spring cannot start till the cuckoo sings. Perhaps that is why the cuckoo is a magical bird. Turn your money when you hear him first, and you'll have money in your pocket until he comes again. Whatever you're doing when you hear him, you'll do most often throughout the year. Especially if you're in bed. No bird is more oracular. It can prophesy how long a man will live and a girl remain a maid. There is no better omen for love than the song of the cuckoo, the beloved bird of folklore. On the other hand, he is the sly creature who gave us the word 'cuckold'. The flattering invocation — to the cuckoo in this widespread song is perhaps in the nature of a magical safeguard for the worried lover.

THE ISLE OF CLOY — The 18th century was an age of country idyll in England. Science was making fields more fertile, stock more stout than ever before. Stubbs was painting his fat farmers on fat horses. An air of prosperity blew over the acres. And perhaps the laborers began to dream of getting some of the prosperity for themselves, for instance by marrying the squire's daughter. Whatever the reason, the story of the servant boy shanghaied to sea by his sweetheart's rich parents came to be the common theme of 18th century folksong. The Isle of Cloy, a song from the east coast of England, offers an unusually dramatic denouement, with the bereft girl hanging from a beam in her cruel father's bedroom.

ABOUT THE SINGER

A. L. LLOYD was born in London in 1908 of musically endowed parents and learned many songs as a hoy, especially from his father, an East-Anglican fisherman. His parents died when he was 14, after which he emigrated to Australia where he worked as a stockman, horsebreaker and shearing roustabout. He took his first conscious interest in folksongs there, learning many from his fellow workers. He extended his first-hand knowledge of songs and singers while working at sea in the 1930's, particularly in Antarctic whaling ships. Today he is a freelance folklorist and journalist, and one of England's leading musicologists. He has written and broadcast a great deal about folk music and folk dance, besides performing on the concert stage and on radio and television. He was the winner of the 1947 National Folk Singing Contest, adjudicated by Ralph Vaughan Williams. He has since made numerous recordings for various companies. Recently John Huston sought him out to play the part of the shantyman in the film version of Moby Dick. During World War II he served with a tank regiment, and during his period of service wrote a brief social-historical introduction to English folksongs entitled The Singing Englishman. In 1932, be published Come All Ye Bold Miners, a collection of songs and ballads of the British mining industry. In 1955, he was appointed general editor of the handbook series Traditional Dances of Latin America. Mr. Lloyd is a member of the editorial hoard of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, and the International Folk Music Council, regularly contributing articles and reviews to the journals of both organizations.