|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

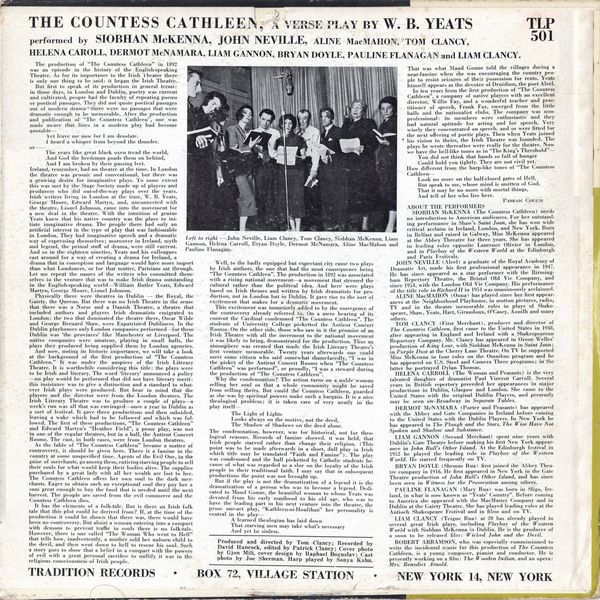

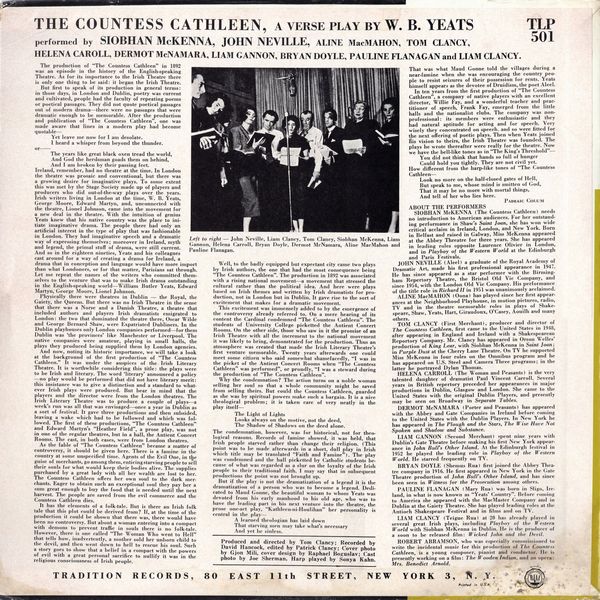

The production of "The Countess Cathleen" in 1892 was an episode in the history of the English–speaking Theatre. As for its importance to the Irish Theatre there is only one thing to be said: it began the Irish Theatre. But first to speak of its production in general terms: in those days, in London and Dublin, poetry was current and cultivated, people had the faculty of repeating poems or poetical passages. They did not quote poetical passages out of modern drama-there were no passages that were dramatic enough to be memorable. After the production and publication of "The Countess Cathleen", one was made aware that lines in a modern play had become quotable —

Yet leave me now for I am desolate.

I heard a whisper from beyond the thunder,

or —

The years like great black oxen tread the world,

And God the herdsman goads them on behind,

And I am broken by their passing feet.

Ireland, remember, had no theatre at the time. In London the theatre was prosaic and conventional, but there was a growing desire for imaginative plays. To some extent this was met by the Stage Society made up of players and producers who did out-of-the-way plays over the years. Irish writers living in London at the time, W. B. Yeats, George Moore, Edward Martyn, and, unconnected with the theatre, Lionel Johnson, came into the movement for a new deal in the theatre. With the intuition of genius Yeats knew that his native country was the place to initiate imaginative drama. The people there had only an artificial interest in the type of play that was fashionable in London. They had imaginative speech and a dramatic way of expressing themselves; moreover in Ireland, myth and legend, the primal stuff of drama, were still current. And so in the eighteen nineties, Yeats and his colleagues cast around for a way of creating a drama for Ireland, a drama that in conception and language would have more import than what Londoners, or for that matter, Parisians sat through. Let me repeat the names of the writers who committed themselves to the venture that was to make Irish drama outstanding in the English-speaking world-William Butler Yeats, Edward Martyn, George Moore, Lionel Johnson.

Physically there were theatres in Dublin — the Royal, the Gaiety, the Queens. But there was no Irish Theatre in the sense that there was a Norse and a Danish Theatre, a theatre that included authors and players Irish dramatists emigrated to London: the two that dominated the theatre there, Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw, were Expatriated Dubliners. In the Dublin playhouses only London companies performed — for them Dublin was 'the provinces' like Manchester or Liverpool. The native companies were amateur, playing in small halls, the plays they produced being supplied them by London agencies.

And now, noting its historic importance, we will take a look at the background of the first production of "The Countess Cathleen." It was under the auspices of the Irish Literary Theatre. It is worthwhile considering this title: the plays were to be Irish and literary. The word 'literary' announced a policy — no play would be performed that did not have literary merit: this insistance was to give a distinction and a standard to whatever Irish plays were produced. But bear in mind that the players and the director were from the London theatres. The Irish Literary Theatre was to produce a couple of plays — a week's run was all that was envisaged — once a year in Dublin as a sort of festival. It gave three productions and then subsided, leaving a wake which had to be followed and which was followed. The first of these productions, "The Countess Cathleen" and Edward Martyn's "Heather Field", a prose play, was not in one of the regular theatres, but in a hall, the Antient Concert Rooms. The cast, in both cases, were from London theatres.

As the fable of "The Countess Cathleen" became a matter of controversy, it should be given here. There is a famine in the country at some unspecified time. Agents of the Evil One, in the guise of merchants, go among them, enticing starving people to sell their souls for what would keep their bodies alive. The supplies purchased by a great lady with all her wealth are lost to her. The Countess Cathleen offers her own soul to the dark merchants. Eager to obtain such an exceptional soul they pay her a sum great enough to buy the food that is needed until the next harvest. The people are saved from the evil commerce and the Countess Cathleen dies.

It has the elements of a folk-tale. But is there an Irish folk tale that this plot could be derived from? If, at the time of the production it could be shown that there was, there would have been no controversy. But about a woman entering into a compact with demons to prevent traffic in souls there is no folk-tale. However, there is one called "The Woman Who went to Hell" that tells how, inadvertently, a mother sold her unborn child to the devil, and then went down to hell to rescue his soul. Such a story goes to show that a belief in a compact with the powers of evil with a great personal sacrifice to nullify it was in the religious consciousness of Irish people.

Well, to the badly equipped but expectant city came two plays by Irish authors, the one that had the most consequence being "The Countess Cathleen". The production in 1892 was associated with a rising national movement — a movement that stressed the cultural rather than the political idea. And here were plays based on Irish themes and written by Irish dramatists for production, not in London but in Dublin. It gave rise to the sort of excitement that makes for a dramatic movement.

This excitement was immensely added to by the emergence of the controversy already referred to. On a mere hearing of its content the Cardinal condemned "The Countess Cathleen". The students of University College picketted the Antient Concert Rooms. On the other side, those who saw in it the promise of an Irish Theatre with all the increment to the national movement it was likely to bring, demonstrated for the production. Thus an atmosphere was created that made the Irish Literary Theatre's first venture memorable. Twenty years afterwards one could meet some citizen who said somewhat shamefacedly, "I was in the picket of the Antient Concert Rooms when "The Countess Cathleen" was performed", or proudly, "I was a steward during the production of "The Countess Cathleen".

Why the condemnation? The action turns on a noble woman selling her soul so that a whole community might be saved from selling theirs. But could the Countess Cathleen, guarded as she was by spiritual powers make such a bargain. It is a nice theological problem; it is taken care of very neatly in the play itself —

The Light of Lights

Looks always on the motive, not the deed,

The Shadow of Shadows on the deed alone.

The condemnation, however, was for historical, not for theological reasons. Records of famine showed, it was held, that Irish people starved rather than change their religion. (This point was to be made afterwards in a short, dull play in Irish which title may be translated "Faith and Famine"). The play was condemned and the hall picketted by Catholic students because of what was regarded as a slur on the loyalty of the Irish people to their traditional faith. I may say that in subsequent productions the point was not brought up.

But if the play is not the dramatization of a legend it is the dramatization of a person who was to become a legend. Dedicated to Maud Gonne, the beautiful woman to whom Yeats was from his early manhood to his old age, who was to tbe leading part in his next venture into the theatre, the one-act play. "Kathleen-ni-Houlihan" her personality is in the play —

A learned theologian has laid down

That starving men may take what's necessary

And yet be be sinless

That was what Maud Gonne told the villages during a near-famine when she was encouraging the country people to resist seizures of their possession for rents. Yeats himself appears as the devotee of Druidism, the poet Aleel. In ten years from the first production of "The Countess Cathleen", a company of native players with an excellent director, Willie Fay, and a wonderful teacher and practitioner of speech, Frank Fay, emerged from the little halls and the nationalist clubs. The company was non-professional: its members were enthusiastic and they had natural aptitude for acting and for speech. Very wisely they concentrated on speech, and so were fitted for the next offering of poetic plays. Then when Yeats joined his vision to theirs, the Irish Theatre was founded. The plays he wrote thereafter were really for the theatre. Now we have the bell-like tones as in "The King's Threshold" —

You did not think that hands so full of hunger

Could hold you tightly. They are not civil yet.

How different from the harp-like tones of "The Countess Cathleen —

Look no more on the half-closed gates of Hell,

But speak to me, whose mind is smitten of God,

That it may be no more with mortal things,

And tell of her who lies here.

PADRAIC COLUM

ABOUT THE PERFORMERS

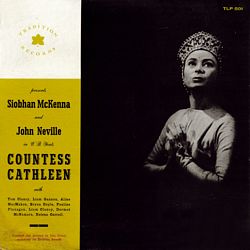

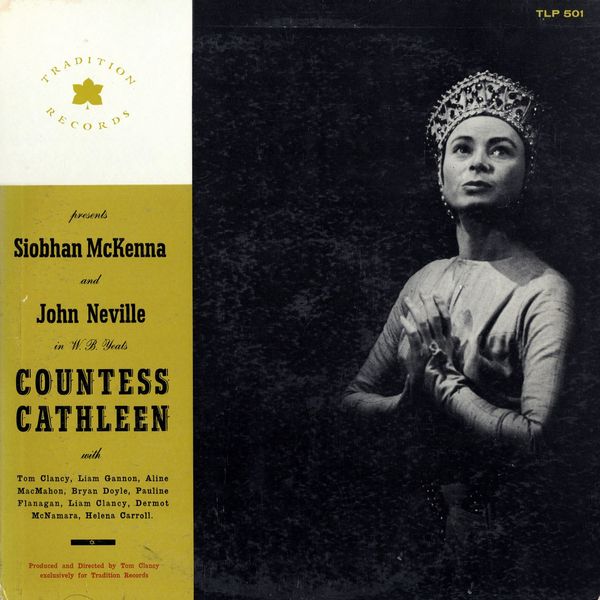

SIOBHAN McKENNA (The Countess Cathleen) needs no introduction to American audiences. For her outstanding performance in Shaw's Saint Joan, she has won wide critical acclaim in Ireland, London, and New York. Born in Belfast and raised in Galway, Miss McKenna appeared at the Abbey Threatre for three years. She has appeared in leading roles opposite Laurence Olivier in London, and in Playboy of the Western World at the Edinburgh and Paris Festivals.

JOHN NEVILLE (Aleel) a graduate of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, made his first professional appearance in 1947. He has since appeared as a star performer with the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, the Bristol Old Vic Company, and since 1954, with the London Old Vic Company. His performance of the title role in Richard II in 1951 was unanimously acclaimed.

ALINE MacMAHON (Oona) has played since her first appearances at the Neighborhood Playhouse, in motion pictures, radio, TV and in the theatre memorable roles in plays of Shakespeare, Shaw, Yeats, Hart, Giraudoux, O'Casey, Aouilh and many others.

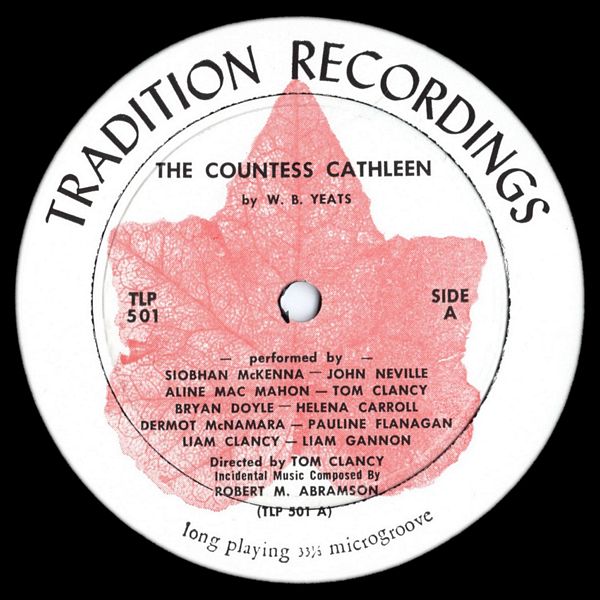

TOM CLANCY (First Merchant), producer and director of The Countess Cathleen, first came to the United States in 1948, after appearing in England and Ireland with a Shakespearean Repertory Company. Mr. Clancy has appeared in Orson Welles' production of King Lear, with Siobhan McKenna in Saint Joan; in Purple Dust at the Cherry Lane Theatre. On TV he supported Miss McKenna in four roles on the Omnibus program and he has appeared on U.S. Steel and Camera Three programs; in the latter he portrayed Dylan Thomas.

HELENA CARROLL (The Woman and Peasants) is the very talented daughter of dramatist Paul Vincent Carroll. Several years in British repertory preceded her appearances in major productions in Dublin, Glasgow and London. She came to the United States with the original Dublin Players, and presently may be seen on Broadway in Separate Tables.

DERMOT McNamara (Porter and Peasants) has appeared with the Abbey and Gate Companies in Ireland before coming to the United States with the Dublin Players. In New York he has appeared in The Plough and the Stars, The Wise Have Not Spoken and Shadow and Substance.

LIAM GANNON (Second Merchant) spent nine years with Dublin's Gate Theatre before making his first New York appearance in John Bull's Other Island. At the Edinburgh festival in 1952 he played the leading role in Playboy of the Western World. He starred frequently on TV.

BRYAN DOYLE (Shemus Rua) first joined the Abbey Theatre company in 1916. He first appeared in New York in the Gate Theatre production of John Bull's Other Island, and has since been seen in Witness for the Prosecution among others.

PAULINE FLANAGAN (Mary Rua) I was born in Sligo. Ireland, in what is now known as "Yeats' Country". Before coming to America she appeared with the MacMaster Company and in Dublin at the Gaiety Theatre. She has played leading roles at the Antioch Shakespeare Festival and in films and on TV.

LIAM CLANCY (Teigue Rua) at 20 has already played in several great Irish plays, including Playboy of the Western World with Siobhan McKenna in Dublin. He is the producer of a soon to be released film: Wicked John and the Devil.

ROBERT ABRAMSON, who was especially commissioned to write the incidental music for this production of The Countess Cathleen, is a young composer, pianist and conductor. He is presently working on a film: The Wooden Indian, and an opera: Mrs, Benedict Arnold.