|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

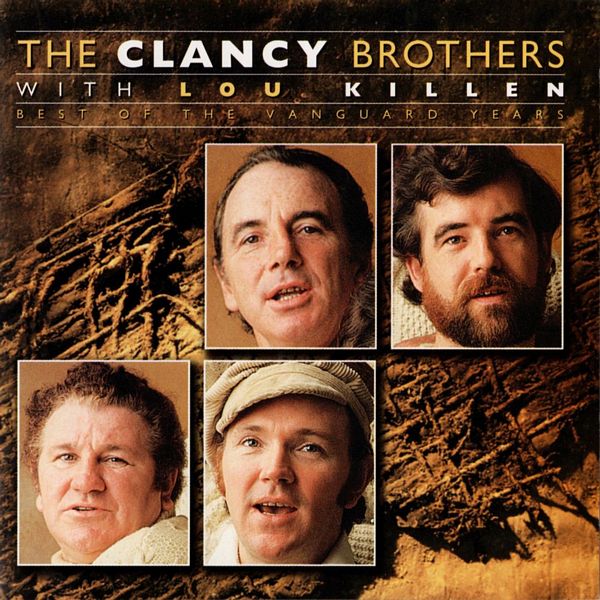

There's never been anything quite like The Clancy Brothers. Hearty of voice, soaring of melody, sly of wit, sharing a lust for life and a touch of the dramatic that never failed to bring audiences to their feet, they burst on the scene in the early 60s.

Armed with rebel songs and drinking songs, songs about life on the high seas and love, requited and not, they took Irish music off the Tin Pan Alley shelves and put it back where it belonged — with the people. In the process, they became an international phenomenon: If you were Irish, they made you proud. If you weren't, they gave you reason to take a very close look at your family tree.

The Clancys were, in short, the real thing: brothers from Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary. From a family of pub owners, their mother, Joan McGrath, was a great song source. Their father, Robert, sold insurance by day and sang at night. Pat was the oldest of nine Clancy siblings, then came Tom. Before they came to the States in the early 50s, they could have written a best-selling novel.

Mavericks of the finest cloth, they had resumes that included tours of duty in the RAF and IRA adventures: at one point Pat mined emeralds in South America, and Tom earned credits on the Irish stage. Liam, the youngest, arrived in America in 1956. Here he joined forces with his brothers and Tommy Makem (Makem's mother, Sarah, was a well-known singer and song collector in County Antrim. The two became friends when Liam and older brother Bobby were gathering material for Tradition Records, the label founded by Pat and Diane Hamilton.) By day, the four worked at odd jobs. Nights were spent singing at pubs (often, literally, for food and drink), with friends and at benefits for Tom's Cherry Lane Theater. They quickly became an integral and popular part of the then-burgeoning Greenwich Village folk music scene.

In 1961, The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem made a now-legendary 16-minute appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show. The rest is history. How they ever survived the bright lights in those Aran sweaters is anyone's guess, but survive they did. From New York to Chicago to Dublin and Sydney, they took the world by storm. Irish tornadoes, they hit the stage singing, and with every show audiences and performers alike could never remember a better time. Fans ranged from the teenager next door to grandparents — and Bob Dylan, who adapted such Clancy standards as "The Parting Glass" for his own material. Everyone knew the words to at least two Clancy songs. Everyone had more than a few albums. They still do.

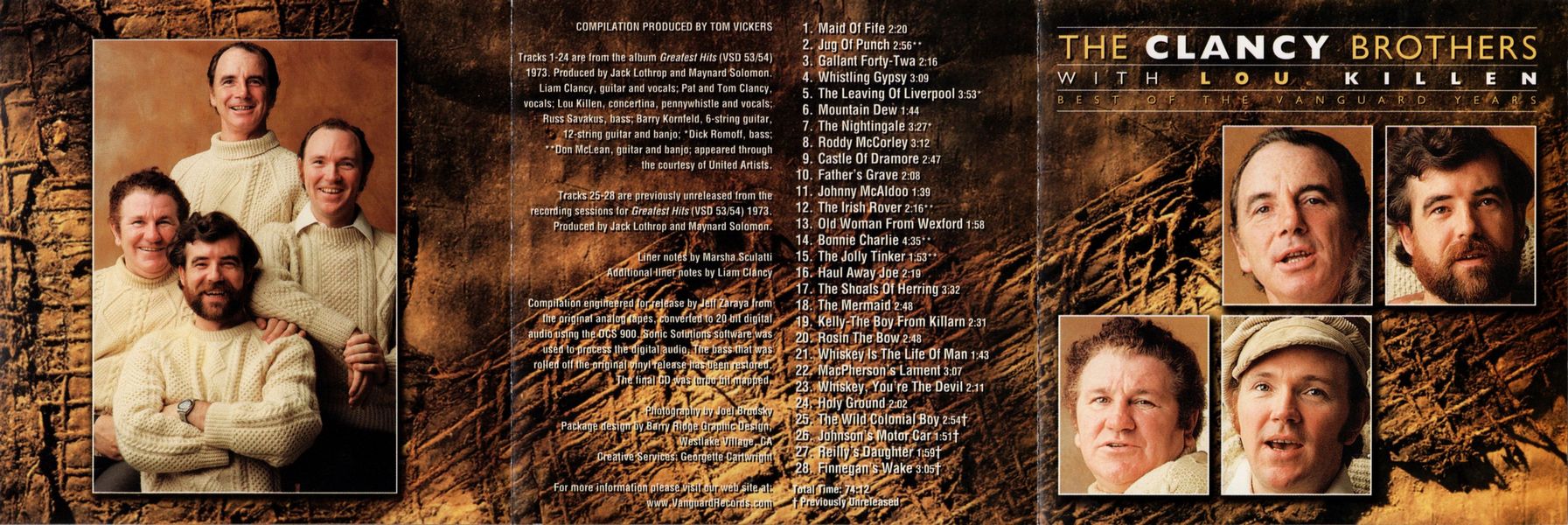

Collectively, the career of The Clancy Brothers encompasses more than 40 years (Tom died in 1990, Pat in 1998. Liam continues to perform), and over 30 albums. In 1965, Maynard Solomon convinced Liam that he should make a solo album for Vanguard (reissued in 1999 with additional material under the title Irish Troubadour). In 1973, Tom and Pat followed Liam's lead and with Louis Killen recorded this album. Originally titled Greatest Hits, this collection of songs (four of which were not on the original release) is among the group's best and brightest.

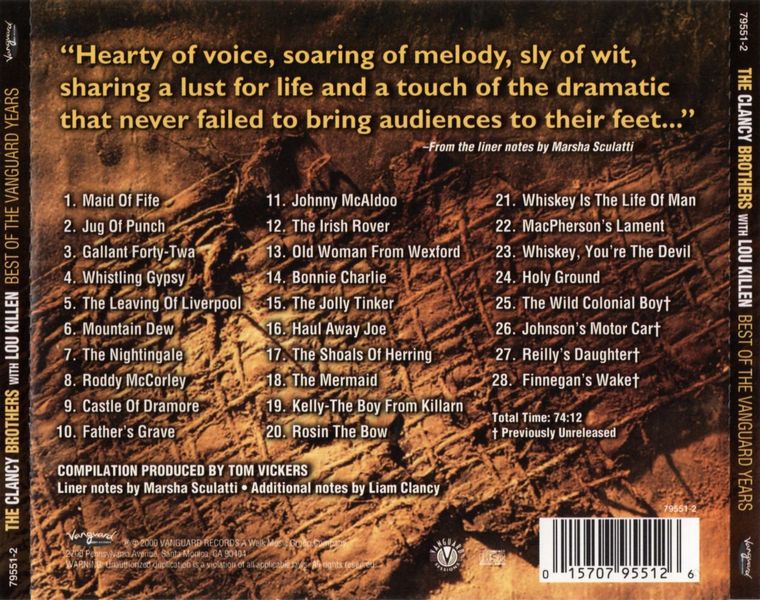

"The Maid Of Fife" opens the album. The song is unusual since it's the soldier, not the woman, who suffers in the end. Pat takes the lead on "Jug Of Punch," well-known in all its variants throughout Ireland. With lilting high spirits, "Gallant Forty-Twa" dates from 19th Century Ulster, where few chances were missed to cheer the hometown regiment or a personal favorite. One of the most beloved of traditional songs, "The Whistling Gypsy" falls under the Clancy spell on this beguiling version with Liam on lead vocals. Liverpool lies across the Irish Sea from Dublin, and many's the Irishman who found employment there when England's clipper ships ruled the seas. "The Leaving of Liverpool" is among the most haunting songs from those times. It's often said that in Ireland you can tell from where a man — or woman — hails by the word they use to describe liquor: "Mountain Dew" is among the euphemisms. More often than not, it's the soldiers, not the women they court, who get off free and easy in relationships: "The Nightingale" is one good example. The Rebellion of 1798 gave Ireland some of her most memorable heroes and songs. Roddy McCorley was a local leader in County Antrim. "Castle of Dramore," as the story goes, is said to date from the 8th Century. A manuscript of the tune was discovered in the ruins of Cashel. Words were written in English, translated into Irish Gaelic and, ultimately, translated back into English. Changing tempos, and all in good fun, "They're Moving Father's Grave (To Build A Sewer)" puts a sly Tom in the lead and the rollicking drama of the dance hall up front.

It's doubtful there was ever a Clancy Brothers concert that didn't include "Johnny McAldoo," Amazing fun, it never failed to bring the house down. Who can resist a sing-along with "The Irish Rover," another example of the fine art of credibilitystretching. The amusing "Old Woman From Wexford" is a song of courting and comeuppance. Led by Charles Edward Stuart, the Jacobite Revolt of 1745 gave us some of Scotland's most-beloved songs: "Bonnie Charlie" is among them. The fact that rogues come in all shapes and sizes isn't news, but the merry spin The Clancys put on it in "The Jolly Tinker" might be. One of the most familiar of sea shanties, "Haul Away Joe" is given lusty treatment here. Ewan MacColl wrote the evocative "Shoals Of Herring" for a BBC special on fishing and fishermen. Though it's still a mystery how she wreaked such havoc with only a mirror and comb, "The Mermaid" is a great frolic. Another song from ‘98, "Kelly The Boy From Killarn" details the untimely end of this dashing leader of the Wexford Rising. "Rosin The Bow," one of the most popular of Irish drinking songs, is followed by a sailors ode to drink, "Whiskey Is The Life Of Man." The gallows and rebels seem to be inextricably intertwined, and so it is in "MacPherson's Lament." "Whiskey You're The Devil" takes us back to good friends and good drink, while good times of another sort abound in "Holy Ground," a song about a district frequented by sailors in Cobh, County Cork.

Australia owes several debts to Ireland, and one of those is "The Wild Colonial Boy." Probably no people have played out their trials and tribulations in story and song with such wit and wisdom as have the Irish: The group has a playful time with it all on "Johnson's Motor Car." Rounding out the album are two of the best-loved songs in the Clancy repertoire: "Reilly's Daughter," and "Finnegan's Wake," said to have inspired one of James Joyce's finest.

For those who were, as they say in Ireland, "bread and buttered" on The Clancy Brothers, this collection is a family reunion. For those about to discover the magic of Pat, Tom and Liam Clancy, ready a welcome for new fast friends for life.

— Marsha Sculatti

Marsha Sculatti first heard The Clancy Brothers in the early 60s. Her life — and the lives of those around her, has never been the same. Special thanks to Liam Clancy, for inspiration, information and all these years of good music; and Larry Caffo and Gene Sculatti for their unending enthusiasm and support.

In the late 60s, I had met Louis Killen at a folk festival in Canada. We got into a sea shanty session in the hotel lounge which grew and grew into a massive male-voice choir in the course of the evening. Louis and I became fast friends, and he started me playing concertina. I lived in an apartment in Greenwich Village at the time and my walls were covered with sheets of tablature invented by Louis for teaching illiterate musicians like myself how to play.

In 1970 (I think), I proposed to Paddy and Tom that we enlist Louis as the fourth member of the group. It turned out to be an ideal combination — Louis playing banjo and guitar as well as concertina, and his strong shanty voice blended perfectly with the belt-'em-out style of The Clancys. A few eyebrows were raised, of course, among our fans when they heard that we now had an Englishman in the group. The thing is, Geordies live on the Scottish borders and don't really think of themselves as English, certainly not in the Maggie Thatcher sort of way. Besides, Louis' father and mother both came from Irish backgrounds.

Maynard Solomon, who founded Vanguard Records, was a good friend of ours, and when our Columbia contract expired he asked us to record with his company. The double LP was his idea. Another friend, Barry Kornfeld, had a large input as well. During those memorable recording sessions on 23rd St. in Manhattan, Barry was "instrumental" — pardon that — in making the songs fly down onto tape. We knew when we started that there were a couple of days in-studio when Barry had other commitments. That's when Louis suggested Don McLean. They had worked together on Pete Seeger's sloop, the Clearwater, before Don had shot to super-stardom with "American Pie" and "Vincent." Louis said in this thick Geordy accent, "We'll give him a try, bonny lad. He can but refuse, and he's no' got a big head." Don McLean agreed instantly, said he was honored to be asked, and insisted on doing the sessions for union rates — $40 a day! They don't make super-stars like that anymore.

The album we ended up with was a collection of the "cream of the crop" from the core of our repertoire of songs. So here they are, enhanced by modern magic, to replace your old, scratched LPs, in crisp, new CD format. Pick your choice at the push of a button — and enjoy!

Liam Clancy, October 1999