|

|

Sleeve Notes

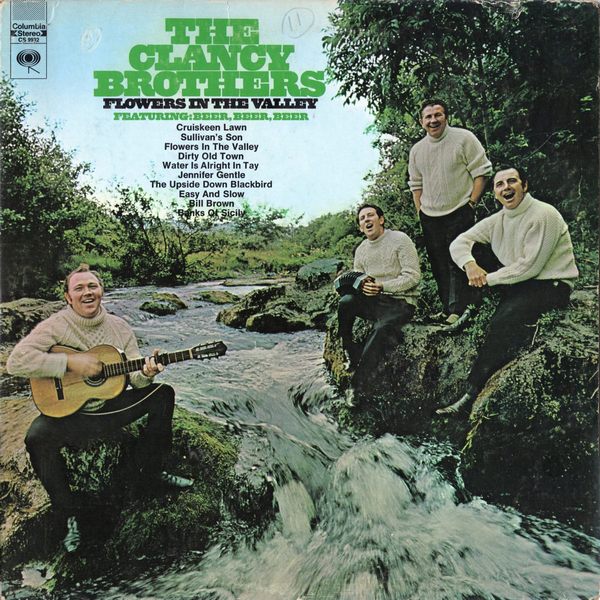

Songs are flowers. They spread out across the valleys of their time, and some of them last only a season. But others throw down roots, down past the surface, down into the rock, and when seasons of cold and bitterness arrive, they withdraw for a while, still there, waiting only for sun. Those are always the best songs, because, like men, they are sworn to endure. It is no accident that these are the songs The Clancy Brothers sing best. The Clancys, like all the good ones, tell us something about ourselves.

I suspect this is because Tom, and Liam, and Pat, and Bobby Clancy have done their research in the best of all places: the human heart. What they sing is, of course, folk music in the best sense of that phrase. But their music has never smelled of the academy; it is not some dry, anthropological tract; it has never been smothered with the false reverence that so many people in the field have brought to it; most important, their music never patronizes.

Instead they sing of the emotions that move all men, whether born in Carrick-on-Suir, in County Tipperary, or in the dark spiky alleys of American cities. I've seen them do their research, sitting late at night in men's saloons, listening to sea chanties, or fragments of Scots ballads, or leftover pieces of songs that men sang against fear and loneliness in places like the Libyan Desert in the Second World War. But the songs they retain, the songs they write down, the songs that they search out for the correct air, are the flowers. And these are the ones that shout out defiance, or celebrate joy, or express remorse, or tell about what happens to men late at night when they understand they are moving out into exile country, and that some things are broken and gone forever.

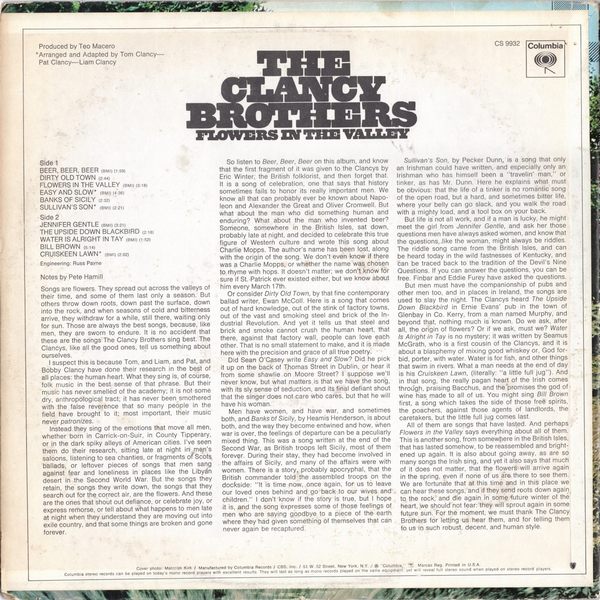

So listen to Beer, Beer, Beer on this album, and know that the first fragment of it was given to the Clancys by Eric Winter, the British folklorist, and then forget that. It is a song of celebration, one that says that history sometimes fails to honor its really important men. We know all that can probably ever be known about Napoleon and Alexander the Great and Oliver Cromwell. But what about the man who did something human and enduring? What about the man who invented beer? Someone, somewhere in the British Isles, sat down, probably late at night, and decided to celebrate this true figure of Western culture and wrote this song about Charlie Mopps. The author's name has been lost, along with the origin of the song. We don't even know if there was a Charlie Mopps, or whether the name was chosen to rhyme with hops. It doesn't matter; we don't know for sure if St. Patrick ever existed either, but we know about him every March 17th.

Or consider Dirty Old Town, by that fine contemporary ballad writer, Ewan McColl. Here is a song that comes out of hard knowledge, out of the stink of factory towns, out of the vast and smoking steel and brick of the Industrial Revolution. And yet it tells us that steel and brick and smoke cannot crush the human heart, that there, against that factory wall, people can love each other. That is no small statement to make, and it is made here with the precision and grace of all true poetry.

Did Seán O'Casey write Easy and Slow? Did he pick it up on the back of Thomas Street in Dublin, or hear it from some shawlie on Moore Street? I suppose we'll never know, but what matters is that we have the song, with its sly sense of seduction, and its final defiant shout that the singer does not care who cares, but that he will have his woman.

Men have women, and have war, and sometimes both, and Banks of Sicily, by Heamis [sic] (Hamish) Henderson, is about both, and the way they become entwined and how, when war is over, the feelings of departure can be a peculiarly mixed thing. This was a song written at the end of the Second War, as British troops left Sicily, most of them forever. During their stay, they had become involved in the affairs of Sicily, and many of the affairs were with women. There is a story, probably apocryphal, that the British commander told the assembled troops on the dockside: "It is time now, once again, for us to leave our loved ones behind and go back to our wives and children." I don't know if the story is true, but I hope it is, and the song expresses some of those feelings of men who are saying goodbye to a piece of the earth where they had given something of themselves that can never again be recaptured.

Sullivan's Son, by Pecker Dunn [sic], is a song that only an Irishman could have written, and especially only an Irishman who has himself been a "travelin' man," or tinker, as has Mr. Dunn. Here he explains what must be obvious: that the life of a tinker is no romantic song of the open road, but a hard, and sometimes bitter life, where your belly can go slack, and you walk the road with a mighty load, and a tool box on your back.

But life is not all work, and if a man is lucky, he might meet the girl from Jennifer Gentle, and ask her those questions men have always asked women, and know that the questions, like the woman, might always be riddles. The riddle song came from the British Isles, and can be heard today in the wild fastnesses of Kentucky, and can be traced back to the tradition of the Devil's Nine Questions. If you can answer the questions, you can be free. Finbar and Eddie Furey have asked the questions.

But men must have the companionship of pubs and other men too, and in places in Ireland, the songs are used to slay the night. The Clancys heard The Upside Down Blackbird in Ernie Evans' pub in the town of Glenbay in Co. Kerry, from a man named Murphy, and beyond that, nothing much is known. Do we ask, after all, the origin of flowers? Or if we ask, must we? Water Is Alright in Tay is no mystery; it was written by Seamus McGrath, who is a first cousin of the Clancys, and it is about a blasphemy of mixing good whiskey or, God forbid, porter, with water. Water is for fish, and other things that swim in rivers. What a man needs at the end of day is his Cruiskeen Lawn, (literally: "a little full jug"). And in that song, the really pagan heart of the Irish comes through, praising Bacchus, and the promises the god of wine has made to all of us. You might sing Bill Brown first, a song which takes the side of those free spirits, the poachers, against those agents of landlords, the caretakers, but the little full jug comes last.

All of them are songs that have lasted. And perhaps Flowers in the Valley says everything about all of them. This is another song, from somewhere in the British Isles, that has lasted somehow, to be reassembled and brightened up again. It is also about going away, as are so many songs the Irish sing, and yet it also says that much of it does not matter, that the flowers will arrive again in the spring, even if none of us are there to see them. We are fortunate that at this time and in this place we can hear these songs, and if they send roots down again to the rock, and die again in some future winter of the heart, we should not fear: they will sprout again in some future sun. For the moment, we must thank The Clancy Brothers for letting us hear them, and for telling them to us in such robust, decent, and human style.