|

|

|

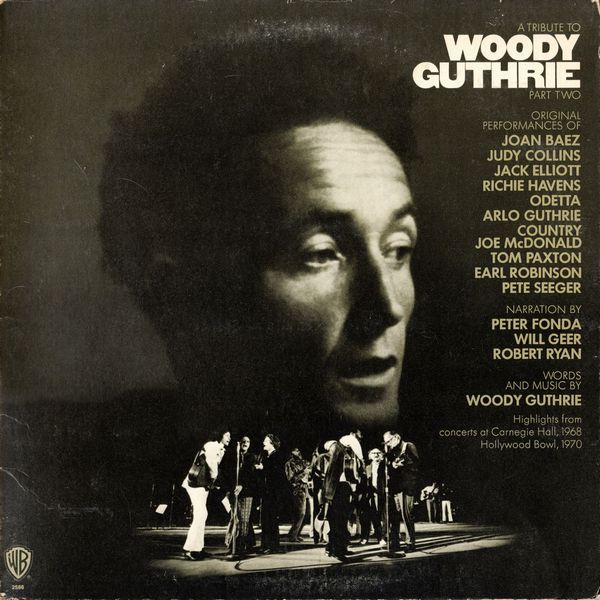

Sleeve Notes

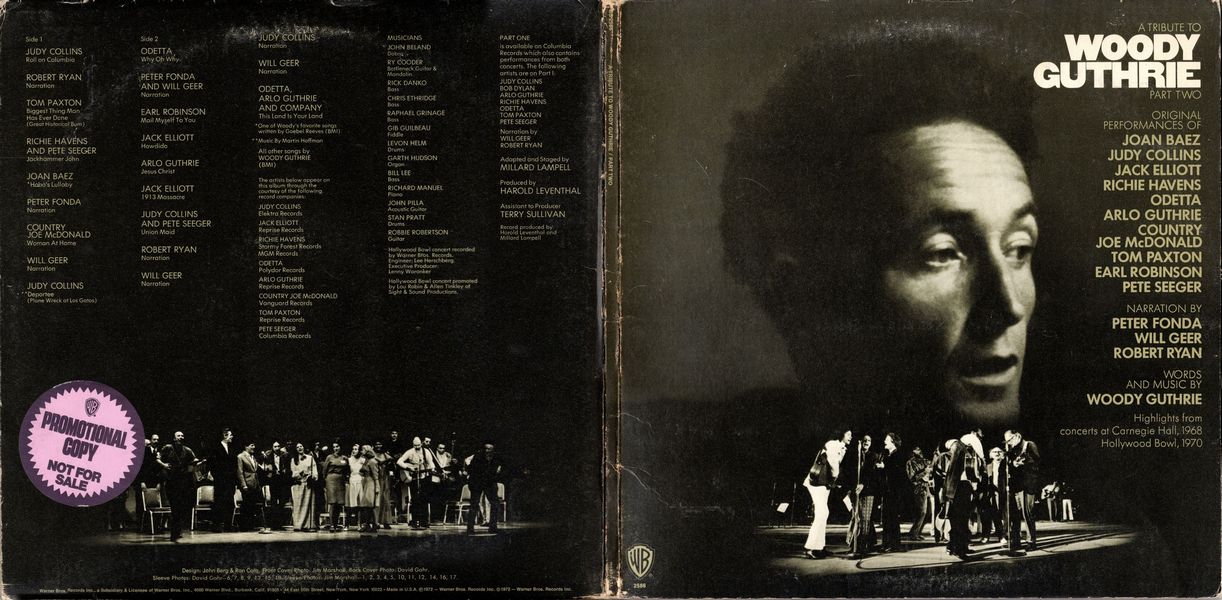

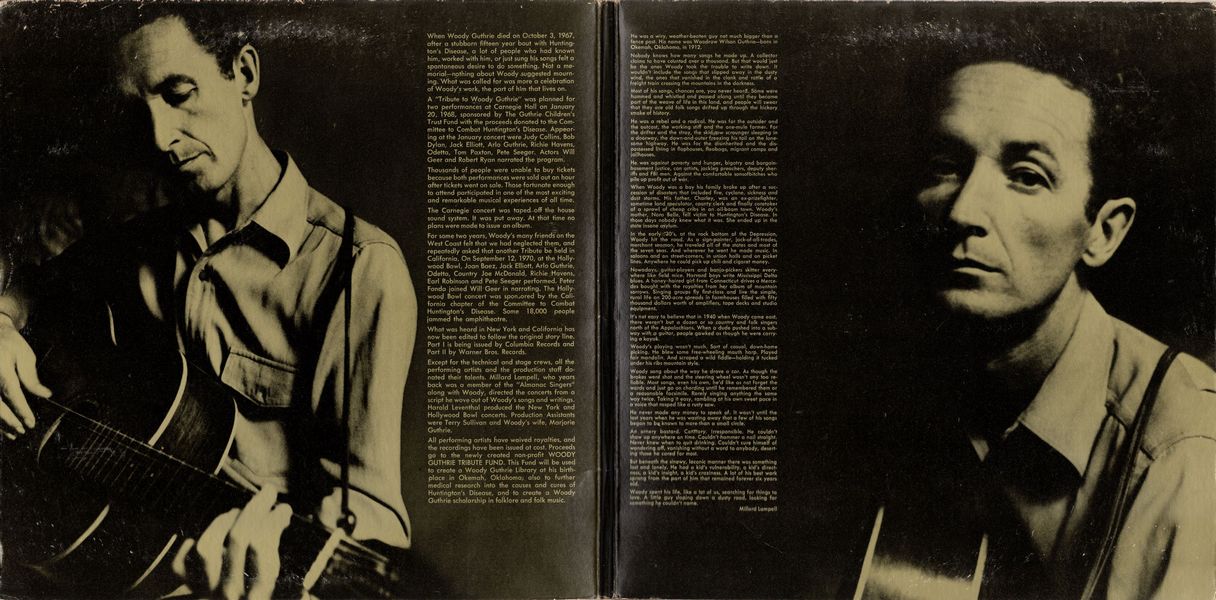

When Woody Guthrie died on October 3, 1967, after a stubborn fifteen year bout with Huntington's Disease, a lot of people who had known him, worked with him, or just sung his songs felt a spontaneous desire to do something. Not a memorial — nothing about Woody suggested mourning. What was called for was more a celebration of Woody's work, the part of him that lives on.

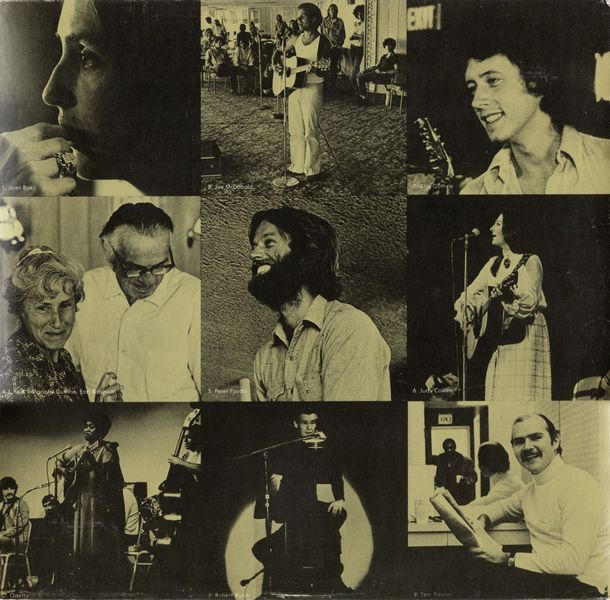

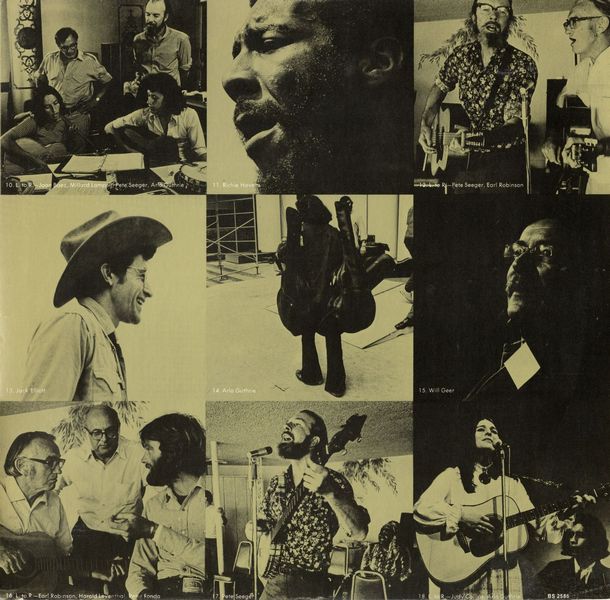

A "Tribute to Woody Guthrie" was planned for two performances at Carnegie Hall on January 20, 1968, sponsored by The Guthrie Children's Trust Fund with the proceeds donated to the Committee to Combat Huntington's Disease. Appearing at the January concert were Judy Collins, Bob Dylan, Jack Elliott, Arlo Guthrie, Richie Havens, Odetta, Tom Paxton, Pete Seeger. Actors Will Geer and Robert Ryan narrated the program.

Thousands of people were unable to buy tickets because both performances were sold out an hour after tickets went on sale. Those fortunate enough to attend participated in one of the most exciting and remarkable musical experiences of all time.

The Carnegie concert was taped off the house sound system. It was put away. At that time no plans were made to issue an album.

For some two years, Woody's many friends on the West Coast felt that we had neglected them, and repeatedly asked that another Tribute be held in California. On September 12, 1970, at the Hollywood Bowl, Joan Baez, Jack Elliott, Arlo Guthrie, Odetta, Country Joe McDonald, Richie Havens, Earl Robinson and Pete Seeger performed. Peter Fonda joined Will Geer in narrating. The Hollywood Bowl concert was sponsored by the California chapter of the Committee to Combat Huntington's Disease. Some 18,000 people jammed the amphitheatre.

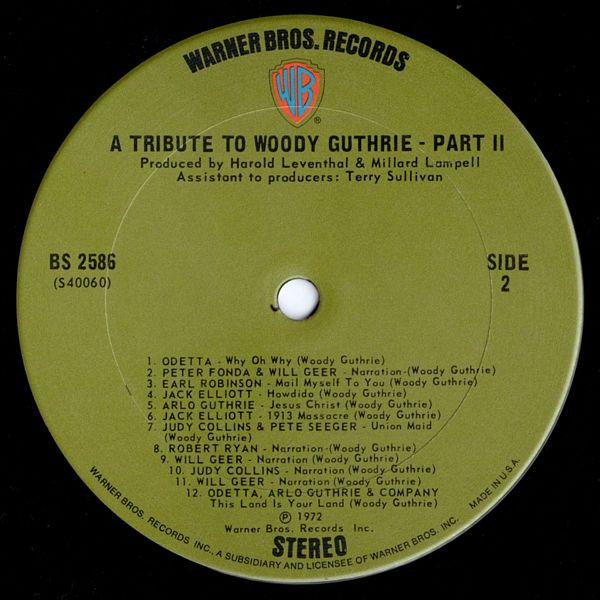

What was heard in New York and California has now been edited to follow the original story line. Part I is being issued by Columbia Records and Part II by Warner Bros. Records.

Except for the technical and stage crews, all the performing artists and the production staff donated their talents. Millard Lampell, who years back was a member of the "Almanac Singers" along with Woody, directed the concerts from a script he wove out of Woody's songs and writings. Harold Leventhal produced the New York and Hollywood Bowl concerts. Production Assistants were Terry Sullivan and Woody's wife, Marjorie Guthrie.

All performing artists have waived royalties, and the recordings have been issued at cost. Proceeds go to the newly created non-profit WOODY GUTHRIE TRIBUTE FUND. This Fund will be used to create a Woody Guthrie Library at his birthplace in Okemah, Oklahoma? also to further medical research into the causes and cures of Huntington's Disease, and to create a Woody Guthrie scholarship in folklore and folk music. He was a wiry, weather-beaten guy not much bigger than a fence post. His name was Woodrow Wilson Guthrie — born in Okemah, Oklahoma, in 1912.

Nobody knows how many songs he made up. A collector claims to have counted over a thousand. But that would just be the ones Woody took the trouble to write down. It wouldn't include the songs that slipped away in the dusty wind, the ones that vanished in the clank and rattle of a freight train crossing the mountains in the darkness.

Most of his songs, chances are, you never heard. Some were hummed and whistled and passed along until they became part of the weave of life in this land, and people will swear that they are old folk songs drifted up through the hickory smoke of history.

He was a rebel and a radical. He was for the outsider and the outcast, the working stiff and the one-mule farmer. For the drifter and the stray, the skid-row scrounger sleeping in a doorway, the down-and-outer freezing his tail on the lonesome highway. He was for the disinherited and the dispossessed living in flophouses, fleabags, migrant camps and jailhouses.

He was against poverty and hunger, bigotry and bargain-basement justice, con artists, jackleg preachers, deputy sheriffs and FBI men. Against the comfortable sonsofbitches who pile up profit out of war.

When Woody was a boy his family broke up after a succession of disasters that included fire, cyclone, sickness and dust storms. His father, Charley, was an ex-prizefighter, sometime land speculator, county clerk and finally caretaker of a sprawl of cheap cribs in an oil-boom town. Woody's mother, Nora Belle, fell victim to Huntington's Disease. In those days nobody knew what it was. She ended up in the state insane asylum.

In the early 30's, at the rock bottom of the Depression, Woody hit the road. As a sign-painter, jack-of-all-trades, merchant seaman, he traveled all of the states and most of the seven seas. And wherever he went he made music. In saloons and on street-corners, in union halls and on picket lines. Anywhere he could pick up chili and cigaret money.

Nowadays, guitar-players and banjo-pickers skitter everywhere like field mice. Harvard boys write Mississippi Delta blues. A honey-haired girl from Connecticut drives a Mercedes bought with the royalties from her album of mountain sorrows. Singing groups fly first-class and live the simple, rural life on 200-acre spreads in farmhouses filled with fifty thousand dollars worth of amplifiers, tape decks and studio equipment

It's not easy to believe that in 1940 when Woody came east, there weren't but a dozen or so country and folk singers north of the Appalachians. When a dude pushed into a subway with a guitar, people gawked as though he were carrying a kayak.

Woody's playing wasn't much. Sort of casual, down-home picking. He blew some free-wheeling mouth harp. Played fair mandolin. And scraped a wild fiddle — holding it tucked Under his ribs mountain style.

Woody sang about the way he drove a car. As though the brakes were shot and the steering wheel wasn't any too reliable. Most songs, even his own, he'd like as not forget the words and just go on chording until he remembered them or a reasonable facsimile. Rarely singing anything the same way twice. Taking it easy, rambling at his own sweet pace in a voice that rasped like a rusty saw.

He never made any money to speak of. It wasn't until the last years when he was wasting away that a few of his songs began to be known to more than a small circle.

An ornory bastard. Contrary. Irresponsible. He couldn't show up anywhere on time. Couldn't hammer a nail straight. Never knew when to quit drinking. Couldn't cure himself of wandering off, vanishing without a word to anybody, deserting those no cared for most.

But beneath the sinewy, laconic manner there was something lost and lonely. Ho had a kid's vulnerability, a kid's directness, a kid's Insight, a kid's craziness. A lot of his best work sprang from the part of him that remained forever six years old.

Woody spent his life, like a lot of us, searching far things to love. A little guy sloping clown a dusty road, looking for something he couldn't name,

Millard Lampell