|

|

|

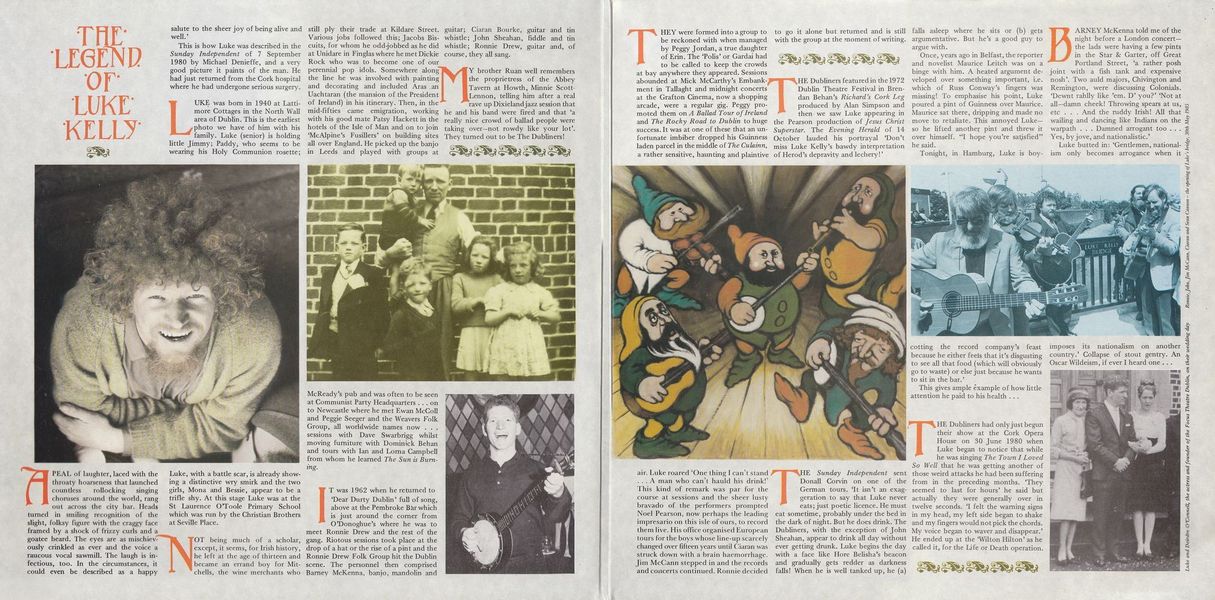

The Legend Of Luke Kelly

A pearl of laughter, laced with the throaty hoarseness that launched countless rollocking singing choruses around the world, rang out across the city bar. Heads turned in smiling recognition of the slight, folksy figure with the craggy face framed by a shock of frizzy curls and a goatee beard. The eyes are as mischievously crinkled as ever and the voice a raucous vocal sawmill. The laugh is infectious, too. In the circumstances, it could even be described as a happy salute to the sheer joy of being alive and well.'

This is how Luke was described in the Sunday Independent of 7 September 1980 by Michael Denieffe, and a very good picture it paints of the man. He had just returned from the Cork hospital where he had undergone serious surgery'.

Luke was born in 1940 at Lattimore Cottages in the North Wall area of Dublin. This is the earliest photo we have of him with his family. Luke (senior) is holding little Jimmy; Paddy, who seems to be wearing his Holy Communion rosette;

Luke, with a battle scar, is already showing a distinctive wry smirk and the two girls, Mona and Bessie, appear to be a trifle shy. At this stage Luke was at the St Laurence O'Toole Primary School which was run by the Christian Brothers at Seville Place.

Not being much of a scholar, except, it seems, for Irish history, he left at the age of thirteen and became an errand boy for Mitchells, the wine merchants who still ply their trade at Kildare Street. Various jobs followed this; Jacobs Biscuits, for whom he odd-jobbed as he did at Unidare in Finglas where he met Dickie Rock who was to become one of our perennial pop idols. Somewhere along the line he was involved with painting and decorating and included Aras an Uachtaran (the mansion of the President of Ireland) in his itinerary. Then, in the mid-fifties came emigration, working with his good mate Patsy Hackett in the hotels of the Isle of Man and on to join 'McAlpine's Fusiliers' on building sites all over England. He picked up the banjo in Leeds and played with groups at McReady's pub and was often to be seen at Communist Party Headquarters … on to Newcastle where he met Ewan McColl and Peggie Seeger and the Weavers Folk Group, all worldwide names now … sessions with Dave Swarbrigg whilst moving furniture with Dominick Behan and tours with Ian and Lorna Campbell from whom he learned The Sun is Burning.

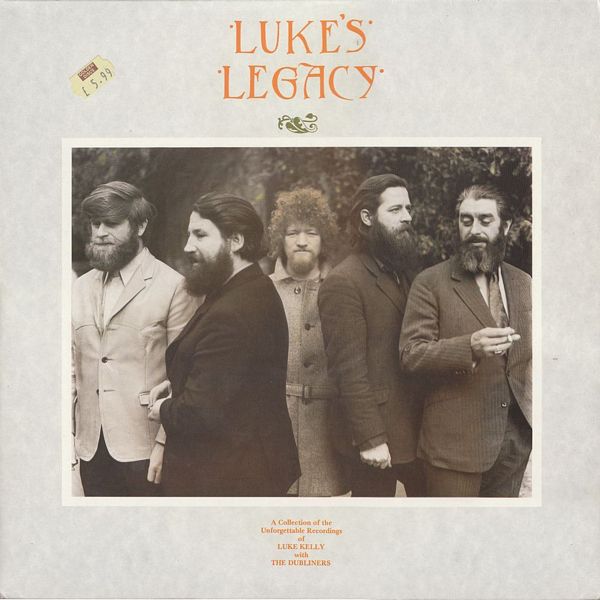

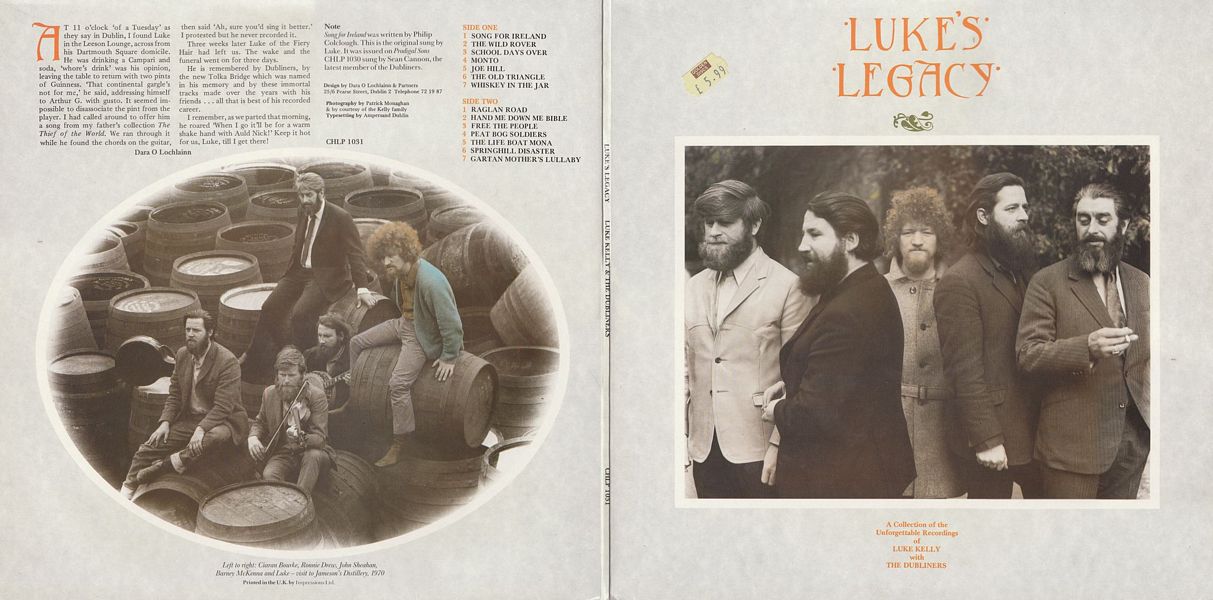

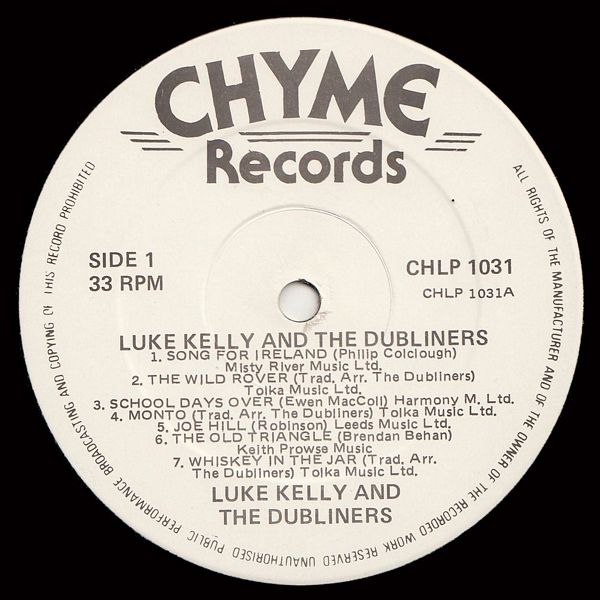

It was 1962 when he returned to 'Dear Durty Dublin' full of song, above at the Pembroke Bar which is just around the corner from O'Donoghue's where he was to meet Ronnie Drew and the rest of the gang. Riotous sessions took place at the drop of a hat or the rise of a pint and the Ronnie Drew Folk Group hit the Dublin scene. The personnel then comprised Barney McKenna, banjo, mandolin and guitar; Ciaran Bourke, guitar and tin whistle; John Sheahan, fiddle and tin whistle; Ronnie Drew, guitar and, of course, they all sang.

My brother Ruan well remembers the proprietress of the Abbey Tavern at Howth, Minnie Scott-Lennon, telling him after a real rave up Dixieland jazz session that he and his band were fired and that 'a really nice crowd of ballad people were taking over — not rowdy like your lot'. They turned out to be The Dubliners!

They were formed into a group to be reckoned with when managed by Peggy Jordan, a true daughter of Erin. The 'Polis' or Gardai had to be called to keep the crowds at bay anywhere they appeared. Sessions abounded at Mick McCarthy's Embankment in Tallaght and midnight concerts at the Grafton Cinema, now a shopping arcade, were a regular gig. Peggy promoted them on A Ballad Tour of Ireland and The Rocky Road to Dublin to huge success. It was at one of these that an unfortunate imbiber dropped his Guinness laden parcel in the middle of The Culainn, a rather sensitive, haunting and plaintive air. Luke roared 'One thing I can't stand … A man who can't hauld his drink!' This kind of remark was par for the course at sessions and the sheer lusty bravado of the performers prompted Noel Pearson, now perhaps the leading impresario on this isle of ours, to record them live. His office organised European tours for the boys whose line-up scarcely changed over fifteen years until Ciaran was struck down with a brain haemorrhage. Jim McCann stepped in and the records and concerts continued. Ronnie decided to go it alone but returned and is still with the group at the moment of writing.

THE Dubliners featured in the 1972 Dublin Theatre Festival in Brendan Behan's Richard's Cork Leg produced by Alan Simpson and then we saw Luke appearing in the Pearson production of Jesus Christ Superstar. The Evening Herald of 14 October lauded his portrayal 'Don't miss Luke Kelly's bawdy interpretation of Herod's depravity and lechery!'

The Sunday Independent sent Donall Corvin on one of the German tours. 'It isn't an exaggeration to say that Luke never eats; just poetic licence. He must eat sometime, probably under the bed in the dark of night. But he does drink. The Dubliners, with the exception of John Sheahan, appear to drink all day without ever getting drunk. Luke begins the day with a face like Hore Belisha's beacon and gradually gets redder as darkness falls! When he is well tanked up, he (a) falls asleep where he sits or (b) gets argumentative. But he's a good guy to argue with.

Once, years ago in Belfast, the reporter and novelist Maurice Leitch was on a binge with him. A heated argument developed over something important, i.e. which of Russ Conway's fingers was missing! To emphasise his point, Luke poured a pint of Guinness over Maurice. Maurice sat there, dripping and made no move to retaliate. This annoyed Luke — so he lifted another pint and threw it over himself. "I hope you're satisfied" he said.

Tonight, in Hamburg, Luke is boycotting the record company's feast because he either feels that it's disgusting to see all that food (which will obviously go to waste) or else just because he wants to sit in the bar.'

This gives ample example of how little attention he paid to his health …

The Dubliners had only just begun their show at the Cork Opera House on 30 June 1980 when Luke began to notice that while he was singing The Town I Loved So Well that he was getting another of those weird attacks he had been suffering from in the preceding months. 'They seemed to last for hours' he said but actually they were generally over in twelve seconds. 'I felt the warning signs in my head, my left side began to shake and my fingers would not pick the chords. My voice began to waver and disappear.' He ended up at the 'Wilton Hilton' as he called it, for the Life or Death operation.

Barney McKenna told me of the night before a London concert — the lads were having a few pints in the Star & Garter, off Great Portland Street, 'a rather posh joint with a fish tank and expensive nosh'. Two auld majors, Chivington and Remington, were discussing Colonials. 'Dewnt rahlly like 'em. D' you?' 'Not at all — damn cheek! Throwing spears at us, etc … And the ruddy Irish! All that wailing and dancing like Indians on the warpath … Damned arrogant too … Yes, by jove, and nationalistic.'

Luke butted in: 'Gentlemen, nationalism only becomes arrogance when it imposes its nationalism on another country.' Collapse of stout gentry. An Oscar Wildeism, if ever I heard one …

At 11 o'clock 'of a Tuesday' as they say in Dublin, I found Luke in the Leeson Lounge, across from his Dartmouth Square domicile. He was drinking a Campari and soda, 'whore's drink' was his opinion, leaving the table to return with two pints of Guinness. 'That continental gargle's not for me,' he said, addressing himself to Arthur G. with gusto. It seemed impossible to disassociate the pint from the player. I had called around to offer him a song from my father's collection The Thief of the World. We ran through it while he found the chords on the guitar, then said 'Ah, sure you'd sing it better.' I protested but he never recorded it.

Three weeks later Luke of the Fiery Hair had left us. The wake and the funeral went on for three days.

He is remembered by Dubliners, by the new Tolka Bridge which was named in his memory and by these immortal tracks made over the years with his friends … all that is best of his recorded career.

I remember, as we parted that morning, he roared 'When I go it'll be for a warm shake hand with Auld Nick!' Keep it hot for us, Luke, till I get there!

Dara O Lochlainn